Art & Photography

Film & tv, life & culture.

The secret history of the essay film

Charting the resurgence of ‘sort of documentaries’ to celebrate chris marker, king of the essay film.

“Essay films are arguably the most innovative and popular form of filmmaking since the 1990s,” wrote Timothy Corrigan in his notable 2011 book, The Essay Film . True, perhaps, but mention of the genre to your average joe won’t spark the instant recognition of today’s romcoms, sci-fis and period dramas. The thing is, essay films have been around since the dawn of cinema: they emerged not long after the Lumière brothers recorded the first ever motion pictures of Lyonnaise factory workers in 1894, yet their definition is still ambiguous.

They are similar to documentary and non-fiction film in that they are often based in reality, using words, images and sounds to convey a message. But according to Chris Darke – co-curator of the Whitechapel Gallery’s current retrospective of the great essay filmmaker Chris Marker – it is “the personal aspect and style of address” that makes the essay film distinct. It is this flexibility that has appealed to contemporary filmmakers, permitting a fresh, nuanced viewing experience.

Geoff Andrew, a senior programmer at the BFI who helped curate last year’s landmark essay film season, explained, “they are sort of documentaries, sort of non-fiction films.” The issue is that some filmmakers try to provide an objective point of view when it is just not possible. “There’s always somebody manipulating footage and manipulating reality to present some sort of message.” Andrew continued, “So, in a way, all documentaries are essay films.”

But the essay film is particularly resurgent these days, with filmmakers like Michael Moore , Werner Herzog , and Nick Broomfield molding the genre in their own ways. Their popularity isn’t just due to incendiary topics like men getting eaten by bears as in Herzog’s Grizzly Man and high school massacres as in Moore’s Bowling for Columbine ; essay films are capable of compelling beauty. Now, with the Whitechapel Gallery ’s retrospective of the late Frenchman, Chris Marker , arguably the greatest essay filmmaker there’s ever been, we take a look at the essay film’s secret history.

1909 - D. W. Griffith ’s A Corner in Wheat

Considered by some to be the first essay film ever, A Corner in Wheat is a little subversive thorn in the side of the man. Lasting only 14 minutes, it tells the tale of a ruthless crop gambler who amasses riches by monopolising the wheat market, exploits the agricultural poor, and is promptly killed under a pile of his own grain. Think twice, greedy capitalists.

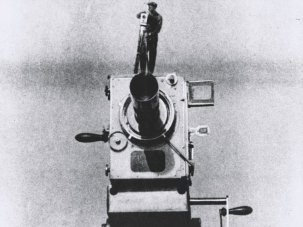

1929 - Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera

“The film drama is the opium of the people,” proclaimed Soviet film pioneer Dziga Vertov , “down with Bourgeois fairy-tale scenarios.” He was the most radical of his fellow Soviet filmmaker compatriots, and Man with a Movie Camera was his masterpiece. In it, he tried to create an “international language of cinema” through a beguiling mix of jump cuts, split screens and superimpositions. Vertov’s idea was to uncover the artifice of filmmaking, with one scene of the film depicting a cameraman inside a giant beer.

1940 - Hans Richter’s The Film Essay

The term “essay film” was originally coined by German artist Hans Richter, who wrote in his 1940 paper, The Film Essay : “The film essay enables the filmmaker to make the ‘invisible’ world of thoughts and ideas visible on the screen... The essay film produces complex thought – reflections that are not necessarily bound to reality, but can also be contradictory, irrational, and fantastic.” So while World War II was blazing away, a new cinema was born.

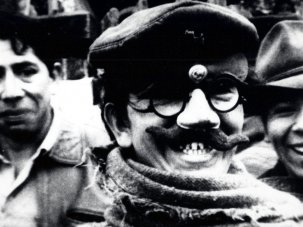

1982 - Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil

You know that this brilliant, freewheeling travelogue is something special when it suggests that Pac-Man is “a perfect graphic metaphor for the human condition.” It takes in anti-colonial struggles, sumo wrestling, a volcanic eruption in Iceland, the antiquities of the Vatican, Marker’s love of cats and more. An unnamed female narrates a circuitous journey from Africa to Japan, in an engaging style never seen before. Some might say he laid down a marker.

1993 - Derek Jarman’s Blue

Diagnosed with HIV and beginning to lose his eyesight, Jarman decided to turn his illness into his art. Although the premise of nothing but a dim, blue background accompanied by voiceovers for 79 minutes might not seem enthralling, it really is. Jarman recalls memories of his past lovers, and his current life of endless pill-popping, with a poignant score by Brian Eno and Simon Fisher Turner .

1998 - Jean -Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinema

Comprised of hundreds of clips of films, music and poetry, this eight part series – that took over a decade to make – remained a secret seen only at a precious few film festivals thanks to the gargantuan amount of rights needed to be cleared. Histoire(s) du cinema is an epic of free association whose central theme is voyeurism, since Godard believes that cinema consists of a man looking at a woman. Harriet Andersson , topless and alluring on a beach in Ingmar Bergman ’s Monika , is one of many examples.

2004 - Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11

The most successful documentary at the US box office ever, Fahrenheit 9/11 is a prime example of the essay film’s wild popularisation (it also won the Palme d’Or at Cannes). Michael Moore ’s swipe at the Republican jugular was a classic example of the essay filmmaker’s prominence, outrightly mocking President George W. Bush and questioning the fairness of his election. Disney refused to distribute the film, and the rest is history.

2010 - Errol Morris’ Tabloid

Tabloid is the outrageous story of a former Miss Wyoming, Joyce McKinney, who was alleged to have kidnapped an American mormon missionary living in England, handcuffed him to a bed in a Devonshire cottage and made him a sex slave. The woman claimed she was saving the man from a cult, but then fleed to Canada wearing a red wig, where she posed as part of a mime troupe. As ever, Errol Morris deftly offers alternate explanations, which led to McKinney suing him after the release of the film.

2014 - Hito Steyerl’s How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educationa l

After touring galleries of the world and a recent stint at the ICA, Hito Steyerl ’s How Not To Be Seen made waves as “an art for our times”. It is a disembowelling satire that mocks the idea that it we can become invisible and have genuine privacy, in this digital age. If we want to disappear, it suggests, we should become poor, or hide in plain sight, or get “disappeared” by the authorities.

Chris Marker: A Grin Without a Cat is on until 22 June at Whitechapel Gallery

Art, documentary and the essay film

PHILOSOPHY OF tHE ESSAY FILM

Art, documentary and the essay film Esther LeslieFilm as document

The moment when Siegfried Kracauer knew that he wanted to write of film as what he terms the ‘Discover of the Marvels of Everyday Life’ is relayed in his introduction to the Theory of Film from 1960.1 Kracauer recalls watching a film long ago that shows a banal scene, an ordinary city street. A puddle in the foreground reflects the houses that cannot be seen and some of the sky. A breeze crosses the site. The puddle’s water trembles. ‘The trembling upper world in the dirty puddle – this image has never left me’, writes Kracauer. In this trembling, which is the moment of nature’s uninvited intervention, its inscription as movement on film, everything, from nature to culture, ‘takes on life’, he notes. What is important about film is its presentation of this given life indiscriminately. The puddle, this unworthy spillage, is redeemed in the low art of cinema. Both cinema and puddle are elevated from the ground. The upper world is brought down to earth as image. Fixed for ever – or for as long as the film strip exists – is a wobble of movement, which comes to stand in for what is life, because it is life captured, being nature’s vitality. It is a life that is possessed by the wind and articulated constantly, but usually expunged from what is to be seen when film is watched. It is a fact, a chip of the world as it is, and it is caught on film or amidst film and the staged world.

Walter Benjamin, in a piece titled ‘Paris, the City in the Mirror’, written for the German edition of Vogue , on 30 January 1929, makes a similar point in relation to photography. [2] In discussing Mario von Bucovich’s volume of Paris photographs from 1928, with its images from Bucovich and Germaine Krull, he posits photography as a mirror of the city. The collection by Bucovich and Krull, he notes, closes with an image of the Seine. It is a close-up of the surface of the water, agitated, dark and light with a hint of cloud broken on its ripples. It seems to him that this reflecting surface is a reflection of photography itself, which is as rightfully there, in the city of looks and looking, as the River Seine, which shatters all images, like a committed montagist, and testifies to the evanescence of all things. Nature, the river, the wind, the clouds passing by all intervene in film, all leave a documentary trace that is seen and not seen at once. Fragments of the world are caught in the grains of the photographic papers. Recorded are both those things that are meant to be seen and those that simply are.

Benjamin’s analysis of Soviet cinema, in critical response to Oskar A.H. Schmitz, twists a sense of enlivened nature, which happily makes itself available for filmic recording, into a more directly politicized physis of the collective labouring body. For him, in his experience of Soviet cinema, there is the entry into film of something not previously bidden into culture and not previously captured in it – the worker, or rather the proletarian, who is part of a collective – set in equivalence to the material nature that marks itself on film, outside of the filmic scenario. An image in Benjamin’s retort to Schmitz makes this graphic.

What began with the bombardment of Odessa in Potemkin continues in the more recent film Mother with the pogrom against factory workers, in which the suffering of the urban masses is engraved in the asphalt of the street like ticker tape. [3]

It is not the wind blowing a puddle, or the reflection of a cloud in the river, caught and remediated on film. It is the labouring body exposed in the stark streets. The film strip absorbs the strip of the road. A place of collective suffering, the street where battles occur, just as the daily grind of life occurs, is given room on the screen. The modern shiny surface of the asphalt road, described elsewhere by Benjamin as a momentous component of the bourgeois city and the bourgeois self, which, like other shiny surfaces, such as windowpanes and mirrors, and the camera too, reflects the city and its residents from many angles. City and residents are fragmented and multiplied, generating feelings of disorientation and loss. Like the running script of a twenty-four-hour news channel, engravings of a modern type, the cinema gives this type and this sensibility a place, a corner of the screen.

Entering too into film are the spaces of this collective. For Benjamin, movement is the key to cinema, but it is not an endless movement or ‘the constant stream of images’ so much as ‘the sudden change of place that overcomes a milieu which has resisted every other attempt to unlock its secret’. [4] It is in relation to this that Benjamin characterizes the locations of cinema, which cannot remain unchanged by the camera’s remediation of them. The passage is well known.

We may truly say that with film a new realm of consciousness comes into being. To put it in a nutshell, film is the prism in which the spaces of the immediate environment – the spaces in which people live, pursue their avocations, and enjoy their leisure – are laid open before their eyes in a comprehensible, meaningful, and passionate way. In themselves, these offices, furnished rooms, saloons, big-city streets, stations, and factories are ugly, incomprehensible, and hopelessly sad. Or rather they were, and seemed to be, until the advent of film. The cinema then exploded this entire prison-world with the dynamite of its fractions of a second, so that now we can take extended journeys of adventure between their widely scattered ruins. [5]

The world is ‘laid open’ and viewers come away with an enhanced knowledge of the structure of actuality through exposure to a prism in which spaces are represented with various types of intensity and fullness, and through which they are led by proletarian heroes, who emerge from and back into collectives, human and spatial collectives. [6] Cinema detonates a ‘prison-world’ – the spaces of this world, his world, are also prison spaces, but the jail can be broken from, filmically, as a first step. Audiences penetrate the secrets contained even in very ordinary reality, once it has been fractured into shards. But those shards are the material of the world, seen from all angles, in close-up, through the fragmenting material of film and its apparatus, and each shard is set next to other shards, other scenarios, and perhaps wordlessly, just as Jan Tschichold and Franz Roh proposed in their volume foto-auge/oeil et photo/photo eye , published in 1929. For example, a photograph by Sasha Stone of alphabetized index cards in a filing cabinet, titled ‘Files’, was placed next to an image, owned by the chemical concern IG Farben, of people relaxing on a beach. The meanings of each – work, leisure, mass society, loss of individuality, public, private, surveillance, bureaucracy – was modulated by the other.

In montage and in absorption of the outlines of the present moment, photography and film proved to be legitimate art forms. As with the polemic against Schmitz for his petty-bourgeois understanding of Battleship Potemkin , Benjamin wrote a caustic response to an article in Die literarische Welt by Friedrich Burschell, published on 20 November 1925. Burschell’s article was a commemorative piece on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the death of the writer Jean Paul and it bemoaned, in its final paragraph, the way in which the anniversary was treated in the popular press, specifically in relation to the use of imagery. Benjamin launched a robust defence of the legitimacy of the montagist, Dada-like sensibility generated by the illustrated press, which in this case had set its images of Jean Paul, miniaturized and cast into a corner, among the children of Thomas Mann, the petty-bourgeois hero of a dubious trial, two tarts all done up in feathers and furs, and two cats and a monkey. Benjamin uses the notion of ‘aura’ here. The images, he notes, exude the ‘aura of their actuality’, in their higgledy-piggledyness, in their thrusting up and out of the chaos of modern life, and in their acknowledgement of the actual social value of things – including cultural figures – rather than the one which they should, apparently, receive from the union formed by technology and capital. It is so incomparably ‘interesting’ precisely because of the rigour with which it concentrates, week after week, in its concave mirror, the dissolute, distracted attention of bank clerks, secretaries, assembly workers. This documentary character is its power and, at the same time, its legitimation. A large head of Jean Paul on the title page of the illustrated magazine – what would be more boring? It is ‘interesting’ only as long as the head remains small. To show things in the aura of their actuality is more valuable, is more fruitful, if indirectly, than crowing on about the ultimately petty-bourgeois idea of educating the general public. [7]

The aura of actuality, the moment of the film or photo, or montage, its absorption into its material of all the contradictions and absurdities of the present, and thereby much that is unbidden, unintended, comes to the fore. Spaces relate to other spaces that have until now been kept apart. Like photography and film itself, meeting its viewer halfway, these new dimensions jut out into the environments of those who take them in their hands.

The films that draw Benjamin’s attention because of their novelty and legitimacy – Battleship Potemkin , Mother , and possibly the film that kindled Kracauer’s interest in film – were not documentaries. They were documentary only in the sense that for Benjamin, as for Kracauer, their basis was in the documentation of actuality that is film and photography. Still Benjamin considered Battleship Potemkin in relation to ‘facts’. The fictional actions of the sadistic ship’s doctor become interesting if facts and statistics can establish that this is not an individual aberration but a portrayal of a social reality in which brutal state and brutal medicine are intertwined and have acted so since the Great War. [8] The fiction caught on film must not be severed from the one in the world that backs it up, becomes its legitimation and makes of it fact. This sets Benjamin’s sense of things in 1927 as a theoretical precursor to Brecht’s later experiment in fiction and actuality, Kuhle Wampe, or To Whom Does the World Belong? , in 1932. That Brecht’s interest was in the way in which fiction may lead towards and not away from social fact was understood, to Brecht’s bemusement, most clearly by the German censor. The film reflected on notions of collective practice – in terms of its production – and in relation to a wider extra-filmic world, in that it relied on the existence of a mass communist and labour movement that were both the audience and stimulus of the film, as well as providing some of the actors for it. The episodic form, the montage and the detached acting style all contributed to a sense in which the film was not about a particular fictionalized individual but rather about the destiny of a collective, a class. In a note on a meeting with the censor, ‘A Small Contribution to the Theme of Realism’ (1932), Brecht explained how the censor had well understood the film’s intent in depicting the suicide of an unemployed man. [9] A young man, after having gone on a futile quest for work, competing against myriad other young Berliners, takes off his watch, the single thing of value on him, and steps off the window ledge of the family’s wretched apartment. This is all done noiselessly, undramatically, in a detached fashion. The censor protested that it did not depict suicide as the abnormal act of an unfortunate individual, but rather, in its impersonality, made suicide seem to be the doom of an entire social class. Brecht and the film company were caught out, and by ‘a policeman’ of all people. Made perceptible in a certain mode of fiction were the actual pressures brought to bear on a class. Drama was simply a pretext for social fact, and social fact on a mass scale at that.

Shub’s work

The Soviet film-maker Esfir Shub worked with a sense of film as conduit to a reality outside of film, which it captures and mobilizes – whether fiction film, documentary or whatever scrap. Film is a piece of actuality, something that could yield knowledge about what exists, once it is deployed in the right way. It is this physically, in that it has absorbed something of a world that passed before it and that may even have been caught unintentionally on the strip. It is this ideologically, in that it has absorbed something of the times and circumstance in which it is made and carries that into the future, where it can be undermined or enstaged. It is this generically, in that film offers itself as an artform in which the facts of the world may be – though not necessarily – reflected and dealt with. All film emerges from the realm of the real, even when it is at its most fake. Film is a material, a raw material ripe for processing. The film is the thing that builds the filmic world and is the thing that is seen. Of course, it is hard to see Esfir Shub because of her authorial anonymity, her use of found footage, grainy, second-hand materials, gathered strips made by nameless filmers. Shub was an editor of films. Or perhaps someone whose labour on film did not even have a name, for she was not simply an editor in the way that many other women were, in terms of their job description, engaged in sorting shots, cutting the negative, but not making even a rough cut of the film. In her work, she did something else. Her editing work for the Soviet film industry from 1922, re-editing and re-titling foreign films, such as Fritz Lang’s Dr Mabuse, Der Spieler or trashy American serials, so that they might become ‘ideologically correct’, involved more than just being an editor. Hers was a key cultural role: in 1924 over 90 per cent of films shown were produced in capitalist countries. In these years of the New Economic Policy, many films were imported. Shub worked on a politically and economically viable solution to a materials crisis, and she learnt how to montage films, producing new meanings from old stock, re-channelling ruling-class ideology. She carried this work over into her own practice as a film-maker, in which she developed a form that predates the canonic essay-film form, but that establishes film as a vehicle for proposing arguments. It does this by amassing fragments of the fictional and non-fictional, drawing together disparate spaces and times, chasing conceptual elements suggestively, by dislocating images from their allotted places, establishing a thematic line out of the disparate, and asserting a directing intelligence, but one that is to be shared by all who watch, as much as by the editor.

Shub’s film The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty was made in 1927, as part of a trilogy on Russian history from 1896, when Lumière filmed the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II. It was one of several films made to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution. It is said that the Soviet film body Sovkino initially refused to acknowledge her authorial rights and pay the royalties that would duly accrue. She is credited on the poster as follows: ‘Work by E.I. Shub’. [10] What was that work? Shub’s film reconstructed critical history out of many metres of newsreel footage and Romanov home movies. Documentary film of whatever type – news, scientific or industrial footage, home movies – could yield information about reality. Shub’s ‘compilation film’ showed the tsar and family at their summer home and on duties of state, the carnage of war and Lenin agitating. For this film, and for the other two ‘compilation films’ she made in the late 1920s, Shub had to amass materials that had, in many cases, been taken out of the country, sold to foreign producers, or had deteriorated under poor storage conditions. For her film covering the first ten years after the October Revolution she was compelled to respond to the monotony of much film produced in newsreels in those years: parades, official celebrations, meetings, delegates arriving, stock that evades all the drama of political reconstruction. To compensate, she shot images of old documents, photographs, newspapers and objects. That this work was only or was blandly ‘work’ is the ‘problem’ attendant on working outside an authorial, directorial mode. But there is, of course, a perfect meeting of Shub’s reuse of found footage, her labour or arrangement or compilation of something conceived as ‘raw material’, and the ideas prevalent among the circles of the Left Front of Arts, the avant-gardist and pro-revolutionary groupings that had surfed the ecstasies of revolution and clamoured for a role in state-building through the arts. They argued that the author was a producer, or more, the author should be effaced, in the collective labour of socially and technically produced and reproduced works of culture. Shub more than others knew what it meant to be anonymous, to genuinely work within the model of the collective, author, the author as producer, the author who rejects all the bourgeois bunkum about creativity, genius and originality.

Shub’s more famous colleague Sergei Eisenstein had paid lip service to this, in a polemic against Bela Balázs. Eisenstein writes: ‘His terminology is unpleasant. Different from ours. “art”, “creativity”, “eternity”, “greatness” and so on.’ [11] Eisenstein, for his part, broke with the grouping around LEF in March 1929, precisely over questions of personal style and authorship. Eisenstein was too much the artist. Eisenstein placed too much of himself in the film. Eisenstein made his films about Eisenstein’s eye and sense of things. As proof of this stood Eisenstein’s celebration as a film-maker in Europe and the fact that US studios sought him out, keen to import a little higher art into their venues.

But Shub’s work did something more than articulate the anonymous, collectivized art worker or engineer, and in so doing sent into relief the practices of another, more prominent documentarist: Dziga Vertov. Shub’s approach signalled a new approach to documentary, overturning the highly montaged, artistic, formalistic documentary films of the early period, as practised by Vertov. Vertov had worked with found footage in 1918, in his Anniversary of the Revolution , and in 1921 in History of the Civil War . But he moved away from the practice in the main. Shub objected to Vertov’s efforts to monopolize non-fiction film, insisting in a piece written in 1926 that ‘different facts must reach the studio’, not just those endorsed by the Futurists working within Vertov’s Kinoks or Cine-Eye. [12] Vertov deployed all manner of tricks and technical devices, derived from the fragmented and dynamic world-view of Futurism, in order to emphasize cinema’s role in mediating reality. Shub’s archival work rescued fact from oblivion and made it speak again in a new context and not to questions of cinematic self-reflection. In her use of archival and documentary footage, or what she called ‘authentic material’, Shub displayed her commitment to the fact, the fact that had become a fetish among the LEF people, who spoke of their work in terms of ‘documentarism’ or ‘factography’. The later 1920s, perhaps under the pressure of waning revolutionary dynamism and conscious of questions of state building, seemed to demand a new aesthetic, which was then matched by Shub. Shub’s was seen to be properly a ‘cinema of fact’.

What is a cinematic fact? This was a question that was asked and answered in relation to Shub’s projects. It was a debate that took place in the pages of the journal Novyi Lef , where one contributor, Sergei Tretyakov, opined that ‘the degree of the deformation of the material out of which the film is composed’ was tantamount to ‘the random personal factor in any given film’. [13] The raw material, the facts that are absorbed by the celluloid strip of the camera, should come before the eyes of the audience as undeformed as possible. The cinematic fact was to appear in as ‘undistorted’ a form as possible. Such a fact is seen to be a building block of a new reality that needed stability after the dynamic change of revolution. Such a fact is like a weapon in the hands of a party entrenching its power and desirous of conveying the upward soaring truth of the young Soviet Union. Shub, it is true, avoided playing with the film material, tending often to let chunks of found film run their course. She gave time to her material, but not simply so. There was a sense, though, in her work that the film material was of historical interest in itself and did not need to be undercut and criticized through cinematic devices.

The commitment to the fact did not imply that any other questions of film were irrelevant. Shub in her capacity as editor worked on questions of compilation, which were questions of montage and rhythm. Connections between events and their interpretation were expressed through juxtapositions, as well as through the times attributed by editing and also through inter-titles. The whole builds up. The whole has direction and compiles an argument that can be seen and borne in mind. It becomes essayistic. Shub wrote that her own ‘emphasis on the fact is an emphasis not only to show the fact, but to enable it to be examined and, having examined it, to be kept in mind’. [14] To watch a film by Shub was to watch reality pass by, moulded, made into concept and argument, a comprehensible concept and argument. Shub was not averse to arguments about skill and even the rhetoric of masterliness. Indeed in 1927 she titled an article ‘We Do Not Reject the Element of Mastery’. The facts, like any raw material, need shaping.

Shub’s work takes the fact and deploys it skilfully.

Her work is planned, and that, of course, at a time when plans are becoming more the focus of political rhetoric and energy. Shub’s relationship to the archive, the place of her raw material, might invite parallels with a bureaucratic approach – congruent with the times – examining the files of reality for evidence, sorting and classifying it for further eyes to pore over. The LEF circle recognized her abnegating act of editing. She also carried out the work of organizing the archive, thereby bequeathing a raw material to those who came after, to all the other films that could be made from it, all the other meanings that might be extracted from this raw material of the real. That was a further service to multiple authorship.

In 1927, Shub argued in the journal Novyi Lef that the controversy between staged and unstaged film was ‘the basic issue of contemporary cinema’. [15] Only documentary cinema could express reality. ‘With great mastery it is possible to make a film from nonplayed material that is better than any fiction film’, she insisted. [16] The polemic was pointed. Shub criticized Eisenstein’s October as a distortion of history, because of its restaging of the historical events of the Russian Revolution. Eisenstein had watched Shub as she worked in the early days and he learnt from her, developing film aesthetics to adequately convey revolution’s reorganizations, its swift changes, its rearticulation of modes of thought and life. She learnt from him in turn, and they led discussions in letters in 1931 over the necessity of ‘developing one’s concept of reality in the process of shooting, and only then subordinating the material to the director’s vision’. [17] But Eisenstein stuck with the played film. Shub was particularly affronted by an actor’s impersonation of Lenin. Why let someone pretend to be Lenin when there is archive footage of the real Lenin? Shub placed film’s power in its capturing of the ‘small fragment of the life that has really passed. Whatever elements it contained.’ [18] Whatever elements it contains and even if it was itself once just a fiction, a slice of ideology, or contaminated by anti-revolutionary values. The ideological circumstances that had produced much of the material did not adhere to the film pieces once they were redeployed in a new context. Ideology could be respun or even overturned. The films’ return revolutionized them. [19]

Revolution is a spin, a re-spin, but not one that repeats – or if it does it is a sign of its failure. A revolution involves another spin, a revolving, an activation into something else – which is movement, a rapid turn and overturning, upturning. Just as the camera turns, spins the exposing film and makes something new happen: the imprinting of an out-there on the in-there of the film strip. Just as the projector turns, revolves, spins the filmed things through its mechanism, in order for them to take on their ghost life, their shadowy and light existence on the screen. Something new happens – the film exists out there, on the screen and is seen. Shub understood that film’s essence lay in its spinning and respinning:

The intention was, not so much to provide the facts, but to evaluate them from the vantage point of the revolutionary class. This is what made my films revolutionary and agitational – although they were composed of counter-revolutionary material. [20]

One film planned in 1933–34 was to be titled Women . Conceived of in seven parts, it was to be about the recent history of female oppression and consequent female liberation by the Bolsheviks. Women were to be shown – through filmic found footage and scripted constructed situations – moving from sexual objectification and class oppression to politically engaged subjects. Shub described her work as ‘artistic documentary’ film. This is a name for a feature-length documentary, but it also implies a level of elevation, of structuring, of making artistic, of forming. The term acknowledges in one concept the proximity of document, of the unplayed, and the structuring, planning or mastering of filmic elements. Shub wrote of the project in a 1933 article titled ‘I Want to Make a Film about Women’:Hitherto it was considered that the non-staged film lacked the possibility of developing events dramatically and that it could not sustain a plot construction within itself. That is why the documentary film was never appreciated by the large audiences. I am aware of this, and in my new documentary film I will try to construct a thematic line. This does not mean that I need to follow the established canons of the staged cinema, nor that I have to use actors to impersonate my characters. Life is so complex and contradictory in everyday situations that it continuously creates dramatic conflicts and resolves them unexpectedly in the most extraordinary way. [21] No one need play anyone who they are not in this film. Reality itself is dramatic enough – and contradictory enough to generate stories, dramas of the type invented for the played film. For Shub, life itself usurps the dramatic function of fiction. Effectively, the artistic documentary can stage the unstaged, can make an art of the document. The treatment or screenplay begins with excerpts from the ‘art’ of the Imperial period. Animation segues a mother into a nude woman, into a Beardsley-style siren – Madonnas, Gretas, Susans created by world-famous artists. Then cinema intervenes. Old film footage shows women as madonnas or whores. One French film heroine is shown in her role as a madonna, then as a fairy. She mutates into other Russian stars, who emulate her. A woman with child in arms appears and morphs into a prostitute, then a peasant. A parade of women appear, all backed by circus music. The exhortation follows to the men of the actual cinema audience: ‘Gentlemen, do you still want to enjoy the face of the ideal woman of the XX century? If so buy the gramophone records. Watch the films produced by Pathé.’ [22] Tragic film incidents from fictional films flash up, shots, strangulations, alienation – ‘Oh my God’ states a woman in a melodrama, ‘What shall I do?’ The fiction of unreal women is brought to the point of real intervention in the world. Shub’s script picks up the question: ‘Indeed she has to do something.’ Shub has provided in a rapid montage a selection of limited stereotypes of women. A comment in the script notes: ‘The movie theatres of Imperial Russia depicted the Russian woman always in the same manner.’ This was, apparently, often fainting into the arms of a man. In the treatment, the words continue to echo: ‘Oh my God! What shall I do? What shall I do?’ These scenes are followed by more examples of how women have been positioned, as fashionable creatures, as targets of advertising concerned about their busts, their waists, belts, as seductresses. Women dependent economically on men, husbands, lovers. What is this sphinx of woman, asks Shub? This is the ideal nature of woman as depicted in the movies. A beauty, sometimes powerful, sometimes vulnerable, but always gorgeous. This intense tumble of ideological images is interrupted by a clown falling through a ceiling, hitting his wife with a rolling pin, such that everything freezes. The audience shouts bravo. The scene of violence against women, the nasty heart of entertainment, serves as a transition. Silence comes. Darkness. The darkness lifts and we are all transported to the countryside. Everything is different. Cinema now has the time of duration, distance, the day, real sounds. Bells are ringing in the far distance. There is a village. There are old women and they go to church. A voice announces that we are at a co-operative farm. Instead of the ideological chit-chatter of films, advertising and religious song, the hum of the motor, speeding us through the space of collective labour, whirrs. This car that moves us through a landscape is, at the same time, a mobile sound movie theatre. It has come, and we the audience have come, to discover the reality of female life in the Soviet Union. Not just how it looks, but how it sounds too – for Shub has found a way to achieve her dream of synched sound, which she discussed in 1929 in an article titled ‘The Arrival of Sound in Cinema’: For us, documentarists, it is crucial to learn how to record the authentic sound: noise, voices, etc., with the same degree of expressiveness as we learned how to photograph the authentic, nonstaged reality. Therefore, we have little interest in what presently goes on in the film studios, in those hermetically insulated theatrical chambers dotted with microphones, sound intensifiers and other techniques. We are interested in the experimental laboratories of the scientists and true creators who can function as our sound operators. [23]

Eisenstein feared that naturalistic sound could destroy montage, and insisted that it be treated as an element of montage – in a way more congruent with the later essay-filmmakers. Shub disagreed, insistent on its importance as an experimental element that remained realist. It was real in the way that Hollywood’s sound system, developed for studio recording not location, was not. It was sound occurring in the spaces where such sounds occur.

Everyone is learning in this new authentic sound world. As the script notes: ‘We place our cameras in front of the window, we arrange the microphone and explain to Comrade Klyazin where he should stand’, in order for his voice to be heard as he asks his questions of the three sisters. This is a film about voice, about speaking the self authentically, though what is authentic is also a matter of history and development. For we hear from Shub that the communist sisters are used to speaking at conferences and therefore talk briskly, while the religious one is more embarrassed. This sonic discrepancy, though, this mark of experience in voice and rhythm, ‘will help us’, she notes, ‘to keep the conversation alive’. We hear examples of the questions the sisters will be asked – ‘The Fascists claim that women must be involved only with the kitchen, the church and children. Do you agree with this?’ Shub writes:We suspect that their answers will be keen and direct. To achieve this, Comrade Klyazin’s questions must be spelled out in such a way that they reveal both the real life and psychology of a typical woman working in the Soviet village. If we succeed, it will be the first direct film interview with the new woman farmer in the USSR. Therefore it has to be done in such a way that the conversation does not look contrived. All we can predict at this moment is that the interview will end with the words: ‘ … now, would you take us to the Selsoviet?’As if as a nod to the role of staging in all this, the final scene of part one takes place in the main offices of the Selsoviet, the rural council. A girl is calling for a revolt, bored with life on the collective farm. Arguments are happening. But, it transpires, it is a drama rehearsal, just a play for the collectives’ theatres, in which the language and appearance of the youth, who are urbanizing, and the traces of peasant language still spoken on the collective farm battle it out. This is a documentary, a capturing of fact that has been shaped by Shub’s concepts, with elements that must be imported from art in order to make ideological sense of the reality which otherwise unfolds. Improvisation can be improved upon, in the name of a larger, greater improvement. Perhaps a negation of the negation is achieved through this. Film never stops being a document, even when it is most fictional, or especially then. The rotten cinema of Weimar, Hollywood and Imperial Russia could have truth squeezed from them, if rightly framed, and so too can the film that moves between fact and staging. The document can supersede all – even the fiction film, even the staged film, is a document of something and if it can be documented, and its factographical powers unleashed, in the interests of the larger history, which is one that is being built, planned, constructed, then it will produce an authentic cinema. In 1932, Shub’s film on the communist youth bared the means of the cinematic device, by leaving cameras and microphones visible in scenes, but it also left in the stumbles and stutters of participants, or shone so bright an arc lamp into their eyes – so assaulted their bodies – that their eyes screwed up. The material of film and cinema directly confront the material of the collective body. The artifice of cinema leaves factual traces on the cinematic subjects. Shub exposed this. In the film script for Woman she notes that the play in the Selsoviet represents a ‘conflict between the urban appearance of the village Komsomol youngsters and the quasi-peasant language the author of the play forces his characters to talk’. The fictionalizing author brutalizes reality, but this is the struggle in play in reality too – the traces of the past that must be re-spun for new meanings to arise from them, new accents to develop out of them. This is what Shub wants to show. It is not that she finds a middle path between Vertov’s Kinoks and cinema of fact and Eisenstein’s staged films; rather, in confronting each mode openly with the other, she makes a third term, another thing, that, among other things, beats out a path for the essay films, or the essay film genre to come.

1. ^ Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality , Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1997, Intro., p. li.

2. ^ See Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften , Vol. IV. [1] , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 1991, pp. 356–9.

3. ^ Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings 1927–1930 , Vol. 2:1, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 2005, p. 18 (translation modified).

4. ^ Ibid., p. 17. 5. Ibid.

6. ^ Ibid., p. 18. 7. Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften , Vol. IV. [1] , pp. 448–9.

8. ^ Benjamin, Selected Writings 1927–1930 , Vol. 2: 1, p. 19.

9. ^ Bertolt Brecht, ‘A Small Contribution to the Theme of Realism’, Screen , vol. 15, no. 2, 1974, pp. 45–7.

10. ^ Jay Leyda, Films Beget Films , George Al en & Unwin,

London, 1964, p. 25.

11. ^ Cited in Martin Stol ery, ‘Eisenstein, Shub and the Gender of the Author as Producer’, Film History , vol. 14, no. 1, Film/ Music (2002), p. 90.

12. ^ Esfir Shub, ‘The Manufacture of Facts’, in Ian Christie and Richard Taylor, eds, The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents 1896–1939 , Routledge, London, 2012, p. 152.

13. ^ Tretyakov cited by Ben Brewster, ‘Lef and Film’, in John Ellis, ed., Screen Reader 1: Cinema/Ideology/Politics , SEFT,

London, 1977, p. 305.

14. ^ Quoted in Mihail Yampolsky, ‘Reality at Second Hand’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol XI, no. 2, June 1991, p. 163.

15. ^ Christie and Taylor, eds, The Film Factory , p. 187. 16. Ibid.

17. ^ Vlada Petric, ‘Esther Shub: Cinema is My Life‘, Quarterly Review of Film Studies , vol. III, no. 4, Fall 1978, p. 434.

18. ^ Christie and Taylor, eds, The Film Factory , p. 187. 19. Despite her criticism of other film-makers – a product of the exciting culture of debate in the young Soviet Union – Shub acted in solidarity as Stalin’s cultural policy tightened its grip. In 1931, while filming in Mexico, Eisenstein was accused in the Soviet journal International Literature of ‘technical fetishism’ and other ‘petty bourgeois limitations’. Shub wrote to him with warning of the increasingly hostile climate and recommending his swift return.

20. ^ Cited in Petric, ‘Esther Shub: Cinema is My Life’, p. 431. 21. Cited in ibid., p. 449.

22. ^ All citations are from the film screenplay or treatment as translated in Petric, ‘Esther Shub: Cinema is My Life’.

23. ^ Cited in Petric, ‘Esther Shub: Film as a Historical Discourse’, in Thomas Waugh, ed., ‘Show Us Life’: Toward a History and Aesthetics of the Committed Documentary , Scarecrow Press, Metuschen NJ, 1984, p. 34.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Essay Film

Introduction, anthologies.

- Bibliographies

- Spectator Engagement

- Personal Documentary

- 1940s Watershed Years

- Chris Marker

- Alain Resnais

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Harun Farocki

- Latin American Cinema

- Installation and Exhibition

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Documentary Film

- Dziga Vertov

- Trinh T. Minh-ha

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Superhero Films

- Wim Wenders

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Essay Film by Yelizaveta Moss LAST REVIEWED: 24 March 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 24 March 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0216

The term “essay film” has become increasingly used in film criticism to describe a self-reflective and self-referential documentary cinema that blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction. Scholars unanimously agree that the first published use of the term was by Richter in 1940. Also uncontested is that Andre Bazin, in 1958, was the first to analyze a film, which was Marker’s Letter from Siberia (1958), according to the essay form. The French New Wave created a popularization of short essay films, and German New Cinema saw a resurgence in essay films due to a broad interest in examining German history. But beyond these origins of the term, scholars deviate on what exactly constitutes an essay film and how to categorize essay films. Generally, scholars fall into two camps: those who find a literary genealogy to the essay film and those who find a documentary genealogy to the essay film. The most commonly cited essay filmmakers are French and German: Marker, Resnais, Godard, and Farocki. These filmmakers are singled out for their breadth of essay film projects, as opposed to filmmakers who have made an essay film but who specialize in other genres. Though essay films have been and are being produced outside of the West, scholarship specifically addressing essay films focuses largely on France and Germany, although Solanas and Getino’s theory of “Third Cinema” and approval of certain French essay films has produced some essay film scholarship on Latin America. But the gap in scholarship on global essay film remains, with hope of being bridged by some forthcoming work. Since the term “essay film” is used so sparingly for specific films and filmmakers, the scholarship on essay film tends to take the form of single articles or chapters in either film theory or documentary anthologies and journals. Some recent scholarship has pointed out the evolutionary quality of essay films, emphasizing their ability to change form and style as a response to conventional filmmaking practices. The most recent scholarship and conference papers on essay film have shifted from an emphasis on literary essay to an emphasis on technology, arguing that essay film has the potential in the 21st century to present technology as self-conscious and self-reflexive of its role in art.

Both anthologies dedicated entirely to essay film have been published in order to fill gaps in essay film scholarship. Biemann 2003 brings the discussion of essay film into the digital age by explicitly resisting traditional German and French film and literary theory. Papazian and Eades 2016 also resists European theory by explicitly showcasing work on postcolonial and transnational essay film.

Biemann, Ursula, ed. Stuff It: The Video Essay in the Digital Age . New York: Springer, 2003.

This anthology positions Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983) as the originator of the post-structuralist essay film. In opposition to German and French film and literary theory, Biemann discusses video essays with respect to non-linear and non-logical movement of thought and a range of new media in Internet, digital imaging, and art installation. In its resistance to the French/German theory influence on essay film, this anthology makes a concerted effort to include other theoretical influences, such as transnationalism, postcolonialism, and globalization.

Papazian, Elizabeth, and Caroline Eades, eds. The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia . London: Wallflower, 2016.

This forthcoming anthology bridges several gaps in 21st-century essay film scholarship: non-Western cinemas, popular cinema, and digital media.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Cinema and Media Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- À bout de souffle

- Accounting, Motion Picture

- Action Cinema

- Advertising and Promotion

- African American Cinema

- African American Stars

- African Cinema

- AIDS in Film and Television

- Akerman, Chantal

- Allen, Woody

- Almodóvar, Pedro

- Altman, Robert

- American Cinema, 1895-1915

- American Cinema, 1939-1975

- American Cinema, 1976 to Present

- American Independent Cinema

- American Independent Cinema, Producers

- American Public Broadcasting

- Anderson, Wes

- Animals in Film and Media

- Animation and the Animated Film

- Arbuckle, Roscoe

- Architecture and Cinema

- Argentine Cinema

- Aronofsky, Darren

- Arzner, Dorothy

- Asian American Cinema

- Asian Television

- Astaire, Fred and Rogers, Ginger

- Audiences and Moviegoing Cultures

- Australian Cinema

- Authorship, Television

- Avant-Garde and Experimental Film

- Bachchan, Amitabh

- Battle of Algiers, The

- Battleship Potemkin, The

- Bazin, André

- Bergman, Ingmar

- Bernstein, Elmer

- Bertolucci, Bernardo

- Bigelow, Kathryn

- Birth of a Nation, The

- Blade Runner

- Blockbusters

- Bong, Joon Ho

- Brakhage, Stan

- Brando, Marlon

- Brazilian Cinema

- Breaking Bad

- Bresson, Robert

- British Cinema

- Broadcasting, Australian

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Burnett, Charles

- Buñuel, Luis

- Cameron, James

- Campion, Jane

- Canadian Cinema

- Capra, Frank

- Carpenter, John

- Cassavetes, John

- Cavell, Stanley

- Chahine, Youssef

- Chan, Jackie

- Chaplin, Charles

- Children in Film

- Chinese Cinema

- Cinecittà Studios

- Cinema and Media Industries, Creative Labor in

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Cinematography and Cinematographers

- Citizen Kane

- City in Film, The

- Cocteau, Jean

- Coen Brothers, The

- Colonial Educational Film

- Comedy, Film

- Comedy, Television

- Comics, Film, and Media

- Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)

- Copland, Aaron

- Coppola, Francis Ford

- Copyright and Piracy

- Corman, Roger

- Costume and Fashion

- Cronenberg, David

- Cuban Cinema

- Cult Cinema

- Dance and Film

- de Oliveira, Manoel

- Dean, James

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Denis, Claire

- Deren, Maya

- Design, Art, Set, and Production

- Detective Films

- Dietrich, Marlene

- Digital Media and Convergence Culture

- Disney, Walt

- Downton Abbey

- Dr. Strangelove

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor

- Eastern European Television

- Eastwood, Clint

- Eisenstein, Sergei

- Elfman, Danny

- Ethnographic Film

- European Television

- Exhibition and Distribution

- Exploitation Film

- Fairbanks, Douglas

- Fan Studies

- Fellini, Federico

- Film Aesthetics

- Film and Literature

- Film Guilds and Unions

- Film, Historical

- Film Preservation and Restoration

- Film Theory and Criticism, Science Fiction

- Film Theory Before 1945

- Film Theory, Psychoanalytic

- Finance Film, The

- French Cinema

- Game of Thrones

- Gance, Abel

- Gangster Films

- Garbo, Greta

- Garland, Judy

- German Cinema

- Gilliam, Terry

- Global Television Industry

- Godard, Jean-Luc

- Godfather Trilogy, The

- Golden Girls, The

- Greek Cinema

- Griffith, D.W.

- Hammett, Dashiell

- Haneke, Michael

- Hawks, Howard

- Haynes, Todd

- Hepburn, Katharine

- Herrmann, Bernard

- Herzog, Werner

- Hindi Cinema, Popular

- Hitchcock, Alfred

- Hollywood Studios

- Holocaust Cinema

- Hong Kong Cinema

- Horror-Comedy

- Hsiao-Hsien, Hou

- Hungarian Cinema

- Icelandic Cinema

- Immigration and Cinema

- Indigenous Media

- Industrial, Educational, and Instructional Television and ...

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers

- Iranian Cinema

- Irish Cinema

- Israeli Cinema

- It Happened One Night

- Italian Americans in Cinema and Media

- Italian Cinema

- Japanese Cinema

- Jazz Singer, The

- Jews in American Cinema and Media

- Keaton, Buster

- Kitano, Takeshi

- Korean Cinema

- Kracauer, Siegfried

- Kubrick, Stanley

- Lang, Fritz

- Latina/o Americans in Film and Television

- Lee, Chang-dong

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Cin...

- Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The

- Los Angeles and Cinema

- Lubitsch, Ernst

- Lumet, Sidney

- Lupino, Ida

- Lynch, David

- Marker, Chris

- Martel, Lucrecia

- Masculinity in Film

- Media, Community

- Media Ecology

- Memory and the Flashback in Cinema

- Metz, Christian

- Mexican Cinema

- Micheaux, Oscar

- Ming-liang, Tsai

- Minnelli, Vincente

- Miyazaki, Hayao

- Méliès, Georges

- Modernism and Film

- Monroe, Marilyn

- Mészáros, Márta

- Music and Cinema, Classical Hollywood

- Music and Cinema, Global Practices

- Music, Television

- Music Video

- Musicals on Television

- Native Americans

- New Media Art

- New Media Policy

- New Media Theory

- New York City and Cinema

- New Zealand Cinema

- Opera and Film

- Ophuls, Max

- Orphan Films

- Oshima, Nagisa

- Ozu, Yasujiro

- Panh, Rithy

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo

- Passion of Joan of Arc, The

- Peckinpah, Sam

- Philosophy and Film

- Photography and Cinema

- Pickford, Mary

- Planet of the Apes

- Poems, Novels, and Plays About Film

- Poitier, Sidney

- Polanski, Roman

- Polish Cinema

- Politics, Hollywood and

- Pop, Blues, and Jazz in Film

- Pornography

- Postcolonial Theory in Film

- Potter, Sally

- Prime Time Drama

- Queer Television

- Queer Theory

- Race and Cinema

- Radio and Sound Studies

- Ray, Nicholas

- Ray, Satyajit

- Reality Television

- Reenactment in Cinema and Media

- Regulation, Television

- Religion and Film

- Remakes, Sequels and Prequels

- Renoir, Jean

- Resnais, Alain

- Romanian Cinema

- Romantic Comedy, American

- Rossellini, Roberto

- Russian Cinema

- Saturday Night Live

- Scandinavian Cinema

- Scorsese, Martin

- Scott, Ridley

- Searchers, The

- Sennett, Mack

- Sesame Street

- Shakespeare on Film

- Silent Film

- Simpsons, The

- Singin' in the Rain

- Sirk, Douglas

- Soap Operas

- Social Class

- Social Media

- Social Problem Films

- Soderbergh, Steven

- Sound Design, Film

- Sound, Film

- Spanish Cinema

- Spanish-Language Television

- Spielberg, Steven

- Sports and Media

- Sports in Film

- Stand-Up Comedians

- Stop-Motion Animation

- Streaming Television

- Sturges, Preston

- Surrealism and Film

- Taiwanese Cinema

- Tarantino, Quentin

- Tarkovsky, Andrei

- Tati, Jacques

- Television Audiences

- Television Celebrity

- Television, History of

- Television Industry, American

- Theater and Film

- Theory, Cognitive Film

- Theory, Critical Media

- Theory, Feminist Film

- Theory, Film

- Theory, Trauma

- Touch of Evil

- Transnational and Diasporic Cinema

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha

- Truffaut, François

- Turkish Cinema

- Twilight Zone, The

- Varda, Agnès

- Vertov, Dziga

- Video and Computer Games

- Video Installation

- Violence and Cinema

- Virtual Reality

- Visconti, Luchino

- Von Sternberg, Josef

- Von Stroheim, Erich

- von Trier, Lars

- Warhol, The Films of Andy

- Waters, John

- Wayne, John

- Weerasethakul, Apichatpong

- Weir, Peter

- Welles, Orson

- Whedon, Joss

- Wilder, Billy

- Williams, John

- Wiseman, Frederick

- Wizard of Oz, The

- Women and Film

- Women and the Silent Screen

- Wong, Anna May

- Wong, Kar-wai

- Wood, Natalie

- Yang, Edward

- Yimou, Zhang

- Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema

- Zinnemann, Fred

- Zombies in Cinema and Media

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, chaz's journal, great movies, contributors, reflexive memories: the images of the cine-essay.

While the video essay form, in regards to its practice of exploring the visual themes in cinematic discourse, has seen a recent surge in popularity with viewers (thanks to invaluable online resources like indieWIRE’s Press Play, Fandor’s Keyframe and the academic peer-reviewed journal [in]Transition), its historical role as a significant filmmaking genre has long been prominent among film scholars and cinephiles.

From the start, the essay film—more affectionately referred to as the “cine-essay”—was a fusion of documentary filmmaking and avant-garde filmmaking by way of appropriation art; it also tended to employ fluid, experimental editing schemes. The first cine-essays were shot and edited on physical film. Significant works like Agnès Varda ’s "Salut les Cubains" (1963) and Marc Karlin’s "The Nightcleaners" (1975), which he made in collaboration with the Berwick Street Film Collective, function like normal documentaries: original footage coupled with a voiceover of the filmmaker and an agenda at hand. But if you look closer and begin to study the aesthetics of the work (e.g. the prolific use of still photos in "Cubains," the transparency of the “filmmaking” at hand in "Nightcleaners"), these films transcend the singular genre that is the documentary form; they became about the process of filmmaking and they aspired to speak to both a past and future state of mind. What the cine-essay began to stand for was our understanding of memory and how we process the images we see everyday. And in a modern technological age of over-content-creation, by way of democratized filmmaking tools (i.e. the video you take on your cell phone), the revitalization of the cine-essayists is ever so crucial and instrumental to the continued curation of the moving images that we manifest.

The leading figure of the cine-essay form, the iconic Chris Marker, really put the politico-stamp of vitality into the cine-essay film with his magnum-opus "Grin Without A Cat" (1977). Running at three hours in length, Marker’s "Grin" took the appropriation art form to the next level, culling countless hours of newsreel and documentary footage that he himself did not shoot, into a seamless, haunting global cross-section of war, social upheaval and political revolution. Yet, what’s miraculous about Marker’s work is that his cine-essays never fell victim to a dependency on the persuasive argument—that was something traditional documentaries hung their hats on. Instead, Marker was much more interested in the reflexive nature of the moving image. If we see newsreel footage of a street riot spliced together with footage from a fictional war film, does that lessen our reaction to the horrific reality of the riot? How do we associate the moving image once it is juxtaposed against something that we once thought to be safe or familiar? At the start of Marker’s "Sans Soleil" (1983), the narrator says, “The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Iceland, in 1965. He said that for him it was the image of happiness and also that he had tried several times to link it to other images, but it never worked. He wrote me: one day I'll have to put it all alone at the beginning of a film with a long piece of black leader; if they don't see happiness in the picture, at least they'll see the black.” It’s essentially the perfect script for deciphering the cine-essay form in general. It demands that we search and create our own new realities, even if we’re forced to stare at a black screen to conjure up a feeling or memory.

Flash forward to 1995: Harun Farocki creates "Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik," a video essay that foils the Lumière brothers’ "Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory" (1895) with countless other film clips of workers in the workplace throughout the century. It’s a significant work: exactly 100 years later, a cine-essayist is speaking to the ideas of filmmakers from 1895 and then those ideas are repurposed to show a historical evolution of employer-employee relations throughout time. What’s also significant about Farocki’s film is the technological aspect. Note how his title at this point in time is a “video essayist.” The advent of video, along with the streamlined workflow to acquiring digital assets of moving images, gave essayist filmmakers like Farocki the opportunity for creating innovative works with faster turnaround times. Not only was it less cumbersome to edit footage digitally, the ways for the works to be presented were altered; Farocki would later repurpose his own video essay into a 12-monitor video installation for exhibition.

Consider Thom Andersen’s epic 2003 video essay "Los Angeles Plays Itself." In it, Andersen appropriates clips from films set in Los Angeles from over the decades and then criticizes the cinema’s depiction of his beloved city. It’s the most meta of essay films because by the end, Andersen himself has constructed the latest Los Angeles-based film. And although Andersen has more of an obvious thesis at hand than, say something as equally lyrical and dense as Marker’s "Sans Soleil," both films exist in the same train of thought: the exploration of the way we as viewers embrace the moving image and then how we communicate that feeling to each other. Andersen may be frustrated with the way Hollywood conveys his city but he even he has moments of inspired introspection towards those films. The same could be said of Marker’s work; just as Marker can remain a perplexed and often inquisitive spectator of the moving images of poverty and genocide that surround him, he functions as a gracious, patient guide for the viewer, since it is his essay text that the narrator reads from.

Watching an essay film requires you to fire on all cylinders, even if you watch one with an audience. It’s a different kind of collective viewing because the images and ideas spring from an artifact that is real; that artifact can be newsreel footage or a completed, a released motion picture that is up for deeper examination or anything else that exists as a completed work. In that sense, the cine-essay (or video essay), remains the most potent form of cinematic storytelling because it invites you to challenge its ideas and images and then in turn, it challenges your own ideas by daring you to reevaluate your own memory of those same moving images. It aims for a deeper truth and it dares to repurpose the cinema less as escapist entertainment and more as an instrument to confront our own truths and how we create them.

RogerEbert.com VIDEO ESSAY: Reflexive Memories: The Images of the Cine-Essay from Nelson Carvajal on Vimeo .

Latest blog posts

13 Films Illuminate Locarno Film Festival's Columbia Pictures Retrospective

Apple TV+'s Pachinko Expands Its Narrative Palate For An Emotional Season Two

Tina Mabry and Edward Kelsey Moore on the Joy and Uplift of The Supremes at Earl's All-You-Can-Eat

The Adams Family Gets Goopy in Hell Hole

Latest reviews.

Simon Abrams

The Becomers

Matt zoller seitz.

The Supremes at Earl's All-You-Can-Eat

Robert daniels.

Brian Tallerico

Between the Temples

Isaac feldberg.

Blink Twice

Peyton robinson.

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media

- The Essay Film: Problems, Definitions, Textual Commitments

- Laura Rascaroli

- Wayne State University Press

- Volume 49, Number 2, Fall 2008

- 10.1353/frm.0.0019

- View Citation

Additional Information

- Buy Article for $9.00 (USD)

- Laura Rascaroli (bio)

The label "essay film" is encountered with ever-increasing frequency in both film reviews and scholarly writings on the cinema, owing to the recent proliferation of unorthodox, personal, reflexive "new" documentaries. In an article dedicated to the phenomenon that he defines as the "recent onslaught of essay films," Paul Arthur proposes: "Galvanized by the intersection of personal, subjective and social history, the essay has emerged as the leading non-fiction form for both intellectual and artistic innovation." 1 Although widely used, the category is under-theorized, even more so than other forms of non-fiction. In spite of the necessary brevity of this contribution, by tracing the birth of the essay in both film theory and film history, and by examining and evaluating existing definitions, a theory of the essay film can be shaped, some order in its intricate field made, and some light shed on this erratic but fascinating and ever more relevant cinematic form.

Most of the existing scholarly contributions acknowledge that the definition of essay film is problematic, and suggest it is a hybrid form that crosses boundaries and rests somewhere in between fiction and nonfiction cinema. According to Giannetti, for instance, "an essay is neither fiction nor fact, but a personal investigation involving both the passion and intellect of the author." 2 Arthur's framing of such in-betweenness is particularly instructive: "one way to think about the essay film is as a meeting ground for documentary, avant-garde, and art film impulses." 3 Nora Alter insists that the essay film is " not a genre, as it strives to be beyond formal, conceptual, and social constraint. Like 'heresy' in the Adornean literary essay, the essay film disrespects traditional boundaries, is transgressive both structurally and conceptually, it is self-reflective and self-reflexive." 4 [End Page 24]

Transgression is a characteristic that the essay film shares with the literary essay, which is also often described as a protean form. The two foremost theorists of the essay are, as is well known, Theodor Adorno and Georg Lukács; both describe it as indeterminate, open, and, ultimately, indefinable. According to Adorno, "the essay's innermost formal law is heresy" 5 ; for Lukács, the essay must manufacture the conditions of its own existence: "the essay has to create from within itself all the preconditions for the effectiveness and solidity of its vision." 6 Other theorists and essayists make similar claims: for Jean Starobinski, the essay "does not obey any rules" 7 ; for Aldous Huxley, it "is a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything" 8 ; for Snyder, it is a "nongenre." 9 As these examples indicate, many existing definitions of both literary and filmic essays are simultaneously vague and sweeping. Indeed, elusiveness and inclusiveness seem to become the only characterizing features of the essayistic; as Renov observes: "the essay form, notable for its tendency towards complication (digression, fragmentation, repetition, and dispersion) rather than composition, has, in its four-hundred-years history, continued to resist the efforts of literary taxonomists, confounding the laws of genre and classification, challenging the very notion of text and textual economy." 10

As José Moure argued, the fact that we resort to a literary term such as "essay" points to the difficulty that we experience when attempting to categorize certain, unclassifiable films. 11 This observation flags the risk that we accept the current state of under-theorization of the form, and use the term indiscriminately, in order to classify films that escape other labeling, as the following remark appears to endorse: "The essayistic quality becomes the only possibility to designate the cinema that resists against commercial productions." 12 The temptation of assigning the label of essay film to all that is non-commercial or experimental or unclassifiable must, however, be resisted, or else the term will cease being epistemologically useful, and we will end up equating very diverse films, as sometimes happens in the critical literature—for instance, works such as Sans Soleil/Sunless (Chris Marker, FR, 1983) and Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, US, 2004), which have very little in common aside the extensive voice-over and the fact that they both...

- Buy Digital Article for $9.00 (USD)

- Buy Complete Digital Issue for $29.00 (USD)

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Historical Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Literature

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- History by Period

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Intellectual History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Language Teaching and Learning

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Christianity

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Browse content in Law

- Company and Commercial Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Criminal Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Legal System and Practice

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Browse content in Economics

- Economic History

- Browse content in Education

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Browse content in Politics

- Asian Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- European Union

- Human Rights and Politics

- International Relations

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Public Policy

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Sociology of Religion

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

1. The Essay Film and its Global Contexts: Conversations on Forms and Practices

- Published: July 2019

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions