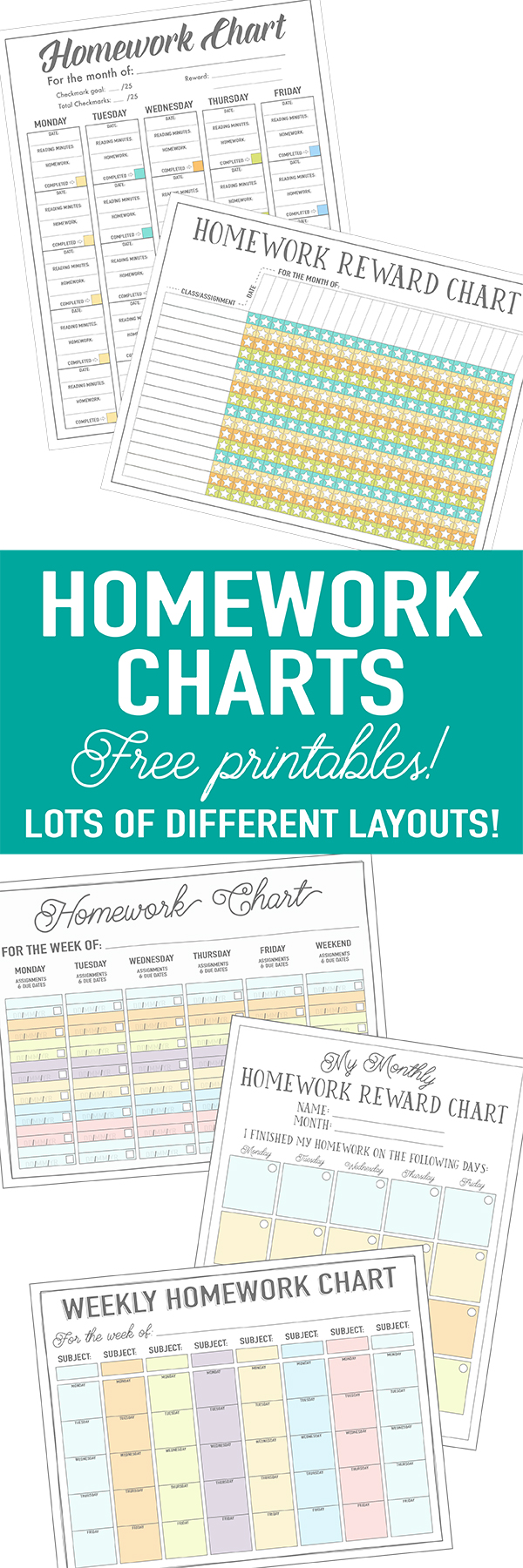

Printable Homework Charts for Teachers & Students

Classroom Homework Charts Introduction

Inspire your students to complete and turn in their homework by using our printable Homework Charts in your classroom. These homework charts work especially well with students who are reluctant to do homework or have a tendency to forget to turn it in. You can also share special Homework Charts with parents to help them with the challenge of homework completion at home. Just share this link .

Chore charts, behavior charts, potty charts, and much more

Behavior charts, award certificates, feelings charts, and much more

Selecting a Homework Chart for Your Students

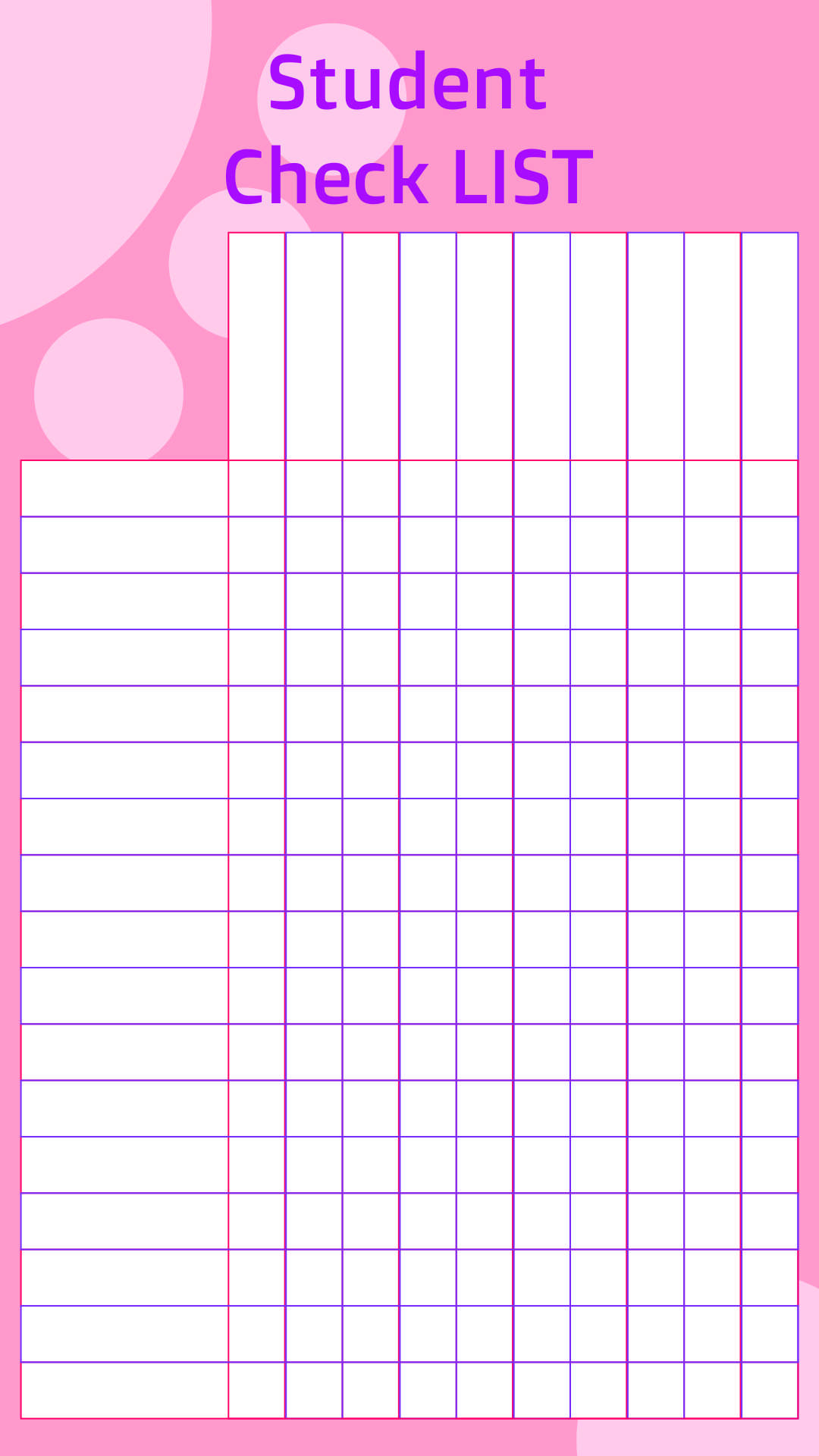

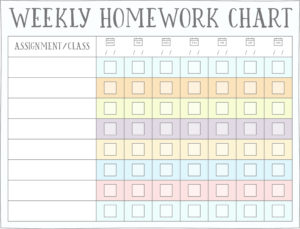

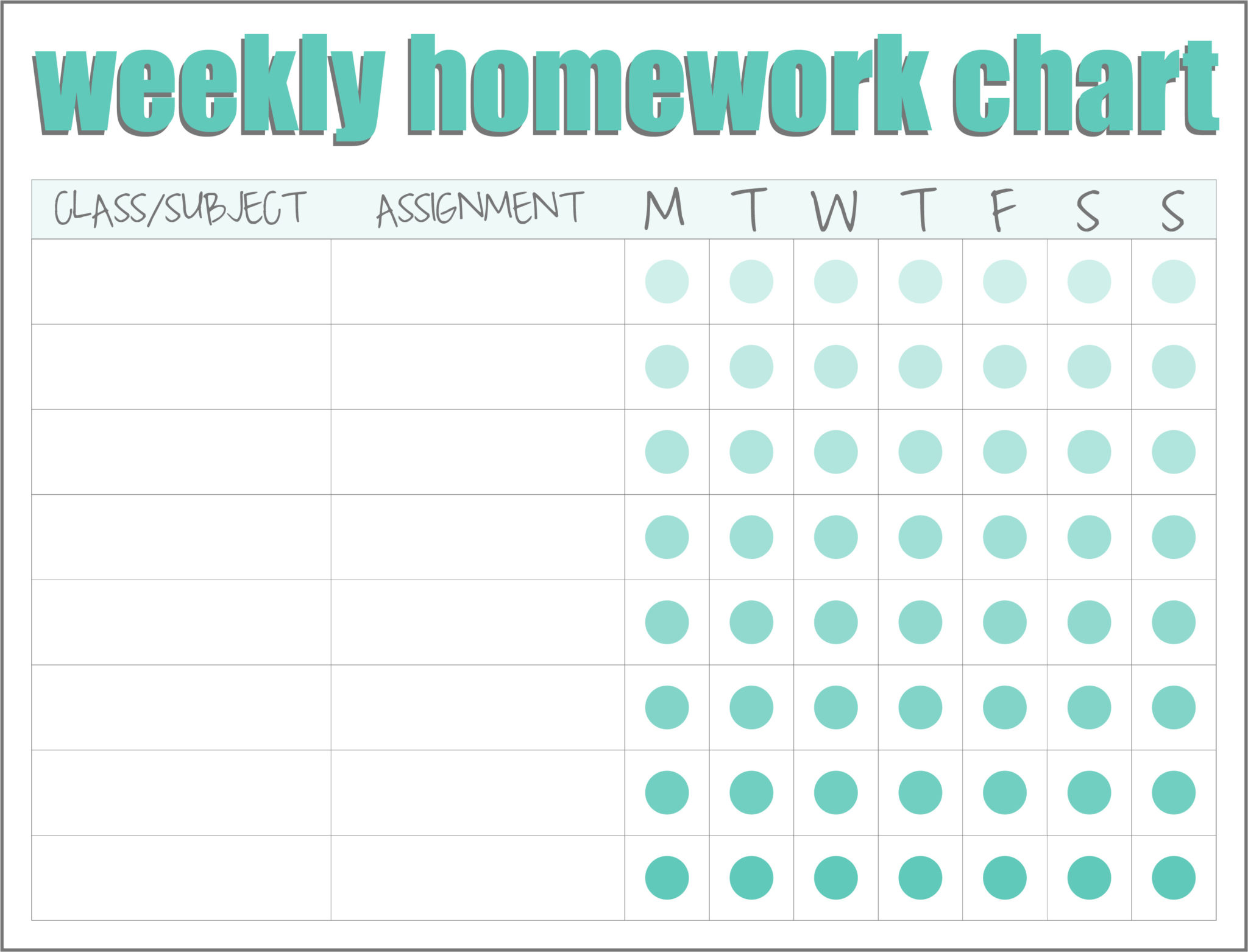

When selecting a Homework Chart, consider whether you want to track homework for one subject or many subjects. If you want to track homework for a single subject, use a Homework Chart that requires five repetitions, one for each day of the week Monday through Friday. If you want to track homework for several subject areas, choose one of the weekly Homework Charts which looks more like a calendar grid and has space for days of the week, as well as headings at the top for each subject area.

Using Our Printable Homework Charts

Using a Homework Chart can help take the stress out of the parental role of making sure homework is completed. When a child or teen understands what is expected and can see the chart posted as a reminder, it can provide a needed nudge. Others need more than a nudge(!) and will need expectations clearly outlined in order to receive an incentive reward.

Keep it Interesting

Watch for new opportunities to celebrate your students’ homework successes. Look for students who are making progress, even if there’s still a lot of room for improvement. Remember that baby steps are cause for celebration, too. Start with simple expectations and grow from there. Aim to keep things fresh, adjusting goals, using new incentives and selecting different charts from our collection.

Enjoy and Have Fun!

If you like using our Classroom Homework Charts, then please use our social share buttons to tell your friends and family about them.

Be sure to check out all of the other charts and printables we offer on our site by navigating our menu. We also suggest for you to follow us on Pinterest for more helpful goodies! We regularly post behavior charts and other useful behavioral tools to our followers.

If you have any ideas on new charts that you would like to see us offer, then please send us a note . We would love to hear from you!

Member Access

Signup Here Lost Password

Homework Checklist

Teachers often face the challenge of keeping track of Homework assignments for various classes. Students struggle to remember which tasks are due when. This disorganization leads to missed deadlines and stress for both sides. A solution is needed to streamline this process, making it easier for everyone to stay on top of assignments. We design easy-to-use homework checklists that can get printed right from your own home. These checklists help students track their assignments, due dates, and completion status. With clear sections and a simple layout, kids can stay organized and motivated to keep on top of their work. It makes life easier for both students and parents to ensure nothing gets missed.

Table of Images 👆

- Student Homework Checklist Editable

- Weekly Homework Charts

- Homework Charts

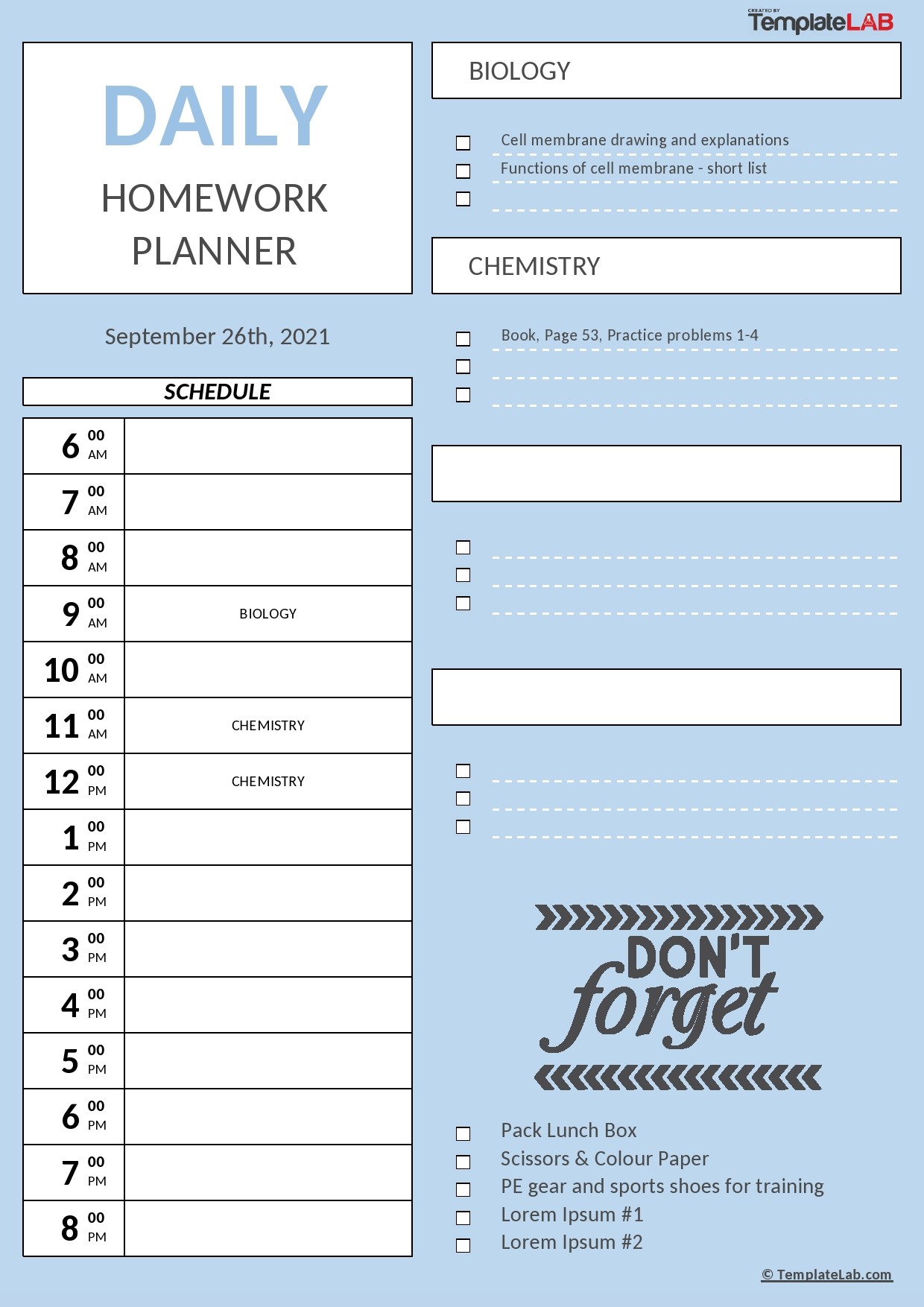

- Daily Homework Checklist

- Homework Chart Template

- Homework Planner Template For College Students

- Weekly Student Homework Checklists

- Weekly Assignment Sheet

- Daily Homework Chart

- Cute To-Do List Template

- Homework Reward Charts

- Classroom Incentive Chart

- Behavior Reward Chart Template

- My School Week Homework Planner For Elementary

- Student Homework Planner Template

A printable homework checklist is a useful tool to help you stay organized and keep track of your assignments. It allows you to list each homework task and mark it off once completed. This checklist can be beneficial for students of all ages, as it helps to prioritize tasks and ensures that nothing is forgotten or overlooked.

Life's too short to be stuck doing assignments all day, right? So, while you're out there making the most of it, Edubirdie got your back with the homework stuff. Think of it like a win-win situation – you keep chasing what you love, and they do the homework .

More printable images tagged with:

Have something to tell us?

Recent Comments

Nov 27, 2022

Thank you for sharing this helpful free printable homework checklist! It's a practical resource that will surely make organizing my assignments easier.

Nov 1, 2022

A free printable homework checklist is a helpful tool to keep track of your assignments and ensure that you stay organized and complete your tasks on time.

Oct 26, 2022

A free printable homework checklist allows students to keep track of their assignments and tasks, ensuring they stay organized and never miss a deadline.

Christmas Gift List Template

Blank Christmas Wish List

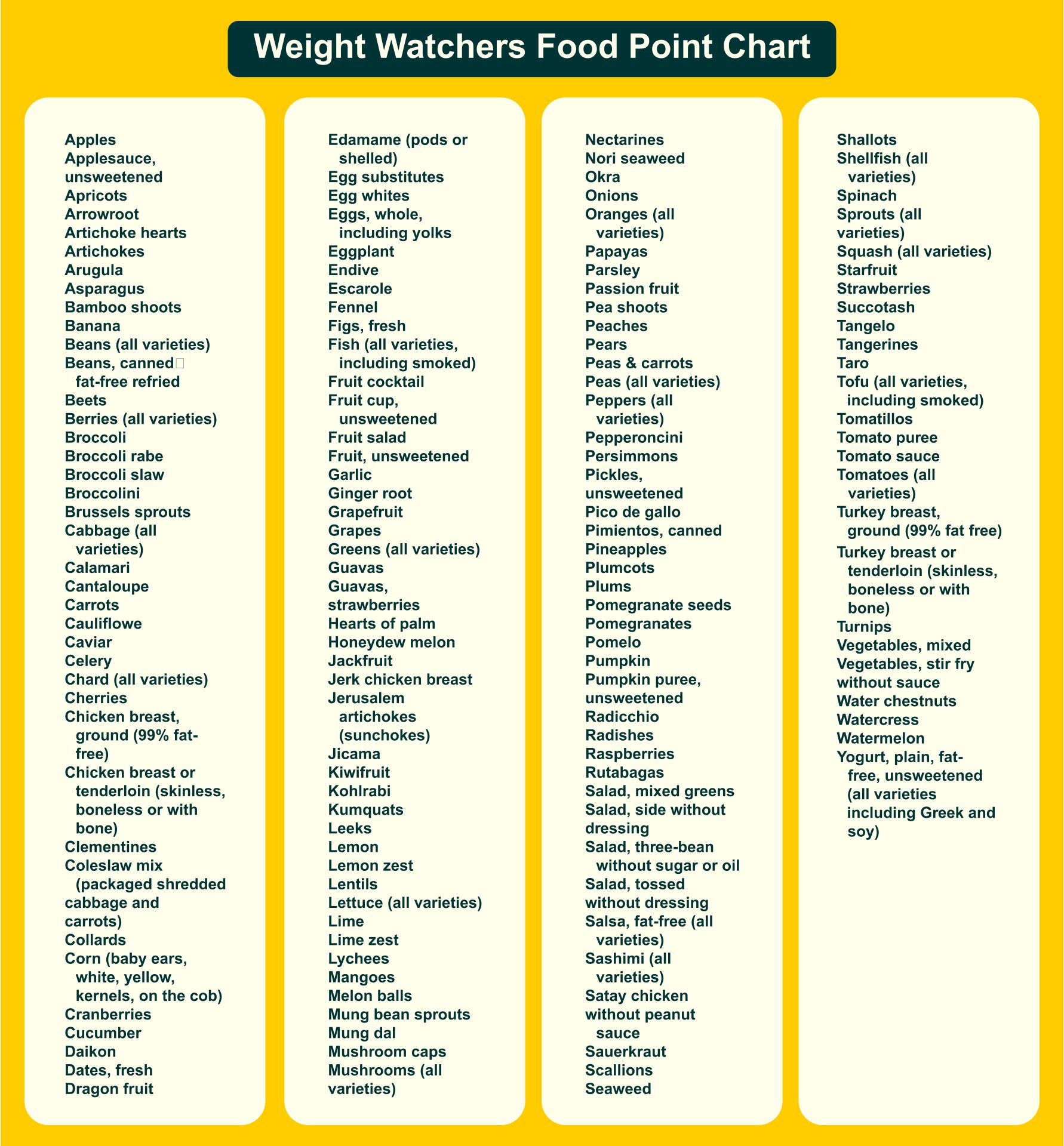

Weight Watchers Points List Foods

Do List Work

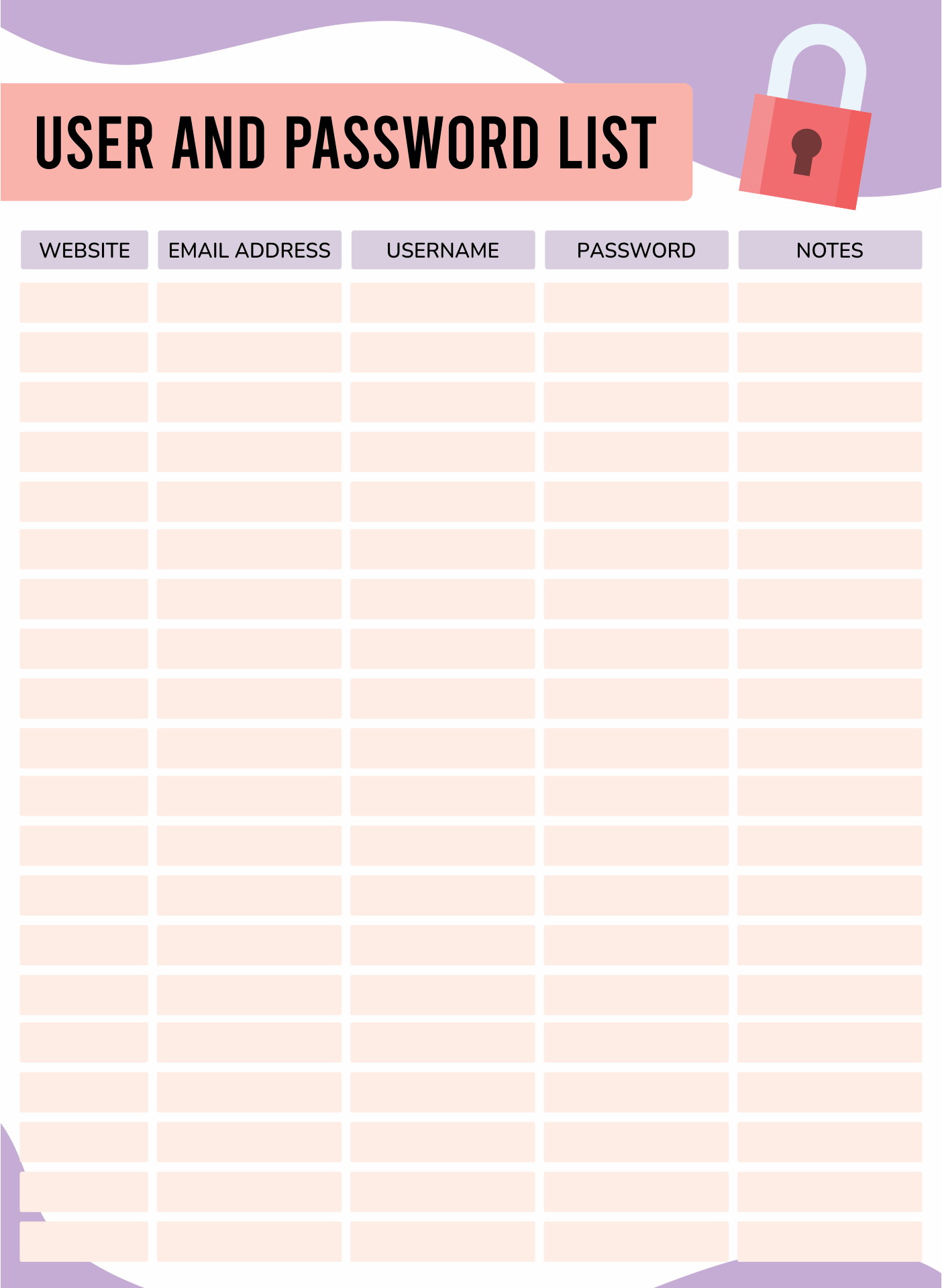

User & Password List

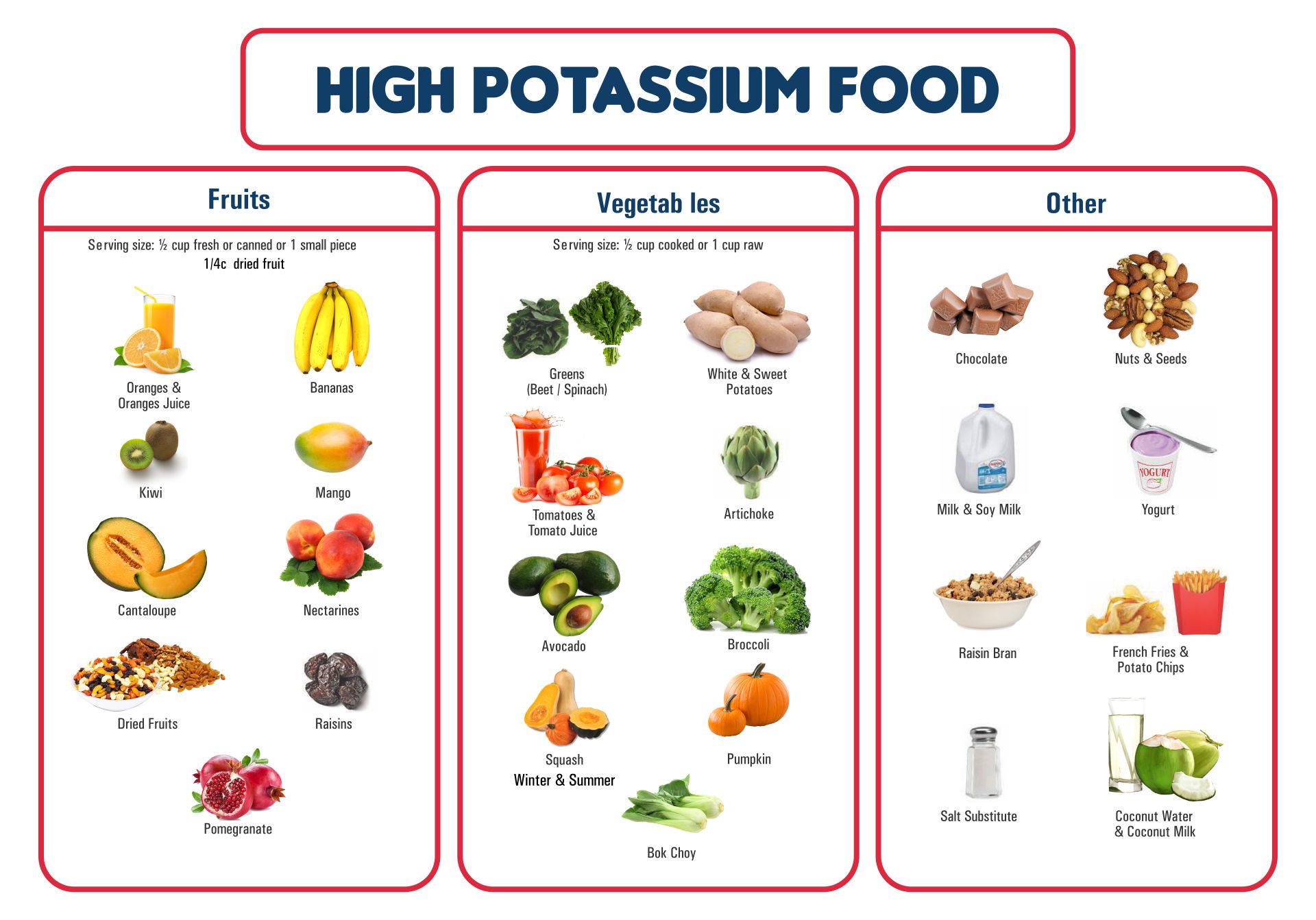

Potassium-Rich Foods List

Find free printable content.

- TemplateLab

- Homework Planners

15 Printable Homework Planners (PDF, Word, Excel)

Just because you’re a student, that doesn’t mean that you always have things under control. A lot of times, you might feel that you “don’t have enough time” because you have so many things to accomplish like school work, projects , review, and homework. To make at least one of these aspects easier, creating a homework planner is essential.

Table of Contents

- 1 Homework Planner Templates

- 2 Information to include in your homework planner

- 3 Tips for creating your own homework planner

- 4 Best Homework Planners

- 5 Using a notebook or binder for your homework planner

- 6 Free Homework Planners

- 7 How to use your homework planner?

Homework Planner Templates

Information to include in your homework planner

If you want to improve your time management skills through a homework planner, make sure to use the planner wisely. Avoid any crisis and conflict by including this information:

- Regular times for you to do your homework

- The due dates of your homework assignments

- The dates of your tests

- Any special events you have to attend wherein you won’t have time for homework

- The deadlines of signing up for standardized tests

- The due dates for school-related fees

- The dates of school holidays

Tips for creating your own homework planner

It can be quite tricky to keep track of all the due dates of your homework without using a homework planner, a student planner template or any other kinds of organizational strategy. If you plan to create your own homework planner printable template, here are some tips:

- Think about the types of weekly homework planner sheets to include. If you want to remain organized, you must use different types of planning lists, one of which is the homework planner printable.

- Select the type and color of the paper to use when you print out your student planner template. You may also want to think about the type of template to use to organize all the information you need for school. After choosing and downloading a template, either customize it according to your needs or use it as it is.

- After printing out the sheets of your daily, monthly or weekly homework planner, arrange the sheets in the order you want them to appear in your binder or notebook. Think about how you plan to use the sheets of your planner to find the perfect arrangement.

- Organizing the different sections of your template allows you to keep all of your similar sheets for planning in one place. This is what successful planners to and it’s what allows you to remain flexible as you deal with your daily tasks.

- Create different sections for your homework planner. Mark these sections using sheets of colored paper, stick-on dividers or other types of dividers to make it easier for you to locate the different sections.

- Design the front cover of your planner. Here, you can express yourself using your own ideas and creativity. You can either create a design on your computer or use craft supplies to come up with a lovely design. If you think it will motivate you more, come up with a design that makes you feel inspired.

- Name the sections of your planner. You can use the different subjects in your school as the names of the sections, the months of the year, and more, depending on what you need.

- After marking the sheets and sections clearly, bind the sheets together. The simplest way to do this is with a stapler. Then fold a strip of paper over the entire side of the bound sheets to give your planner a neat look. After this, you can start using your planner!

Best Homework Planners

Using a notebook or binder for your homework planner

Apart from creating your homework planner from scratch, you can also use either a notebook or a binder. Here are some steps to guide you:

Standard notebook

- Select a notebook to use. Although using a homework planner printable is very convenient, decorating a notebook and using it for your planner is an excellent way for you to express yourself.

- Decorate the notebook by starting with the cover. Use paint, stickers, and other craft supplies to do this.

- Divide the notebook into how many sections you need for your planner. Think about how many sections you need then think about how many pages of the notebook you need for each of the sections.

- Label the sections either by hand or using printed labels. You can also decorate the label covers of the notebook as you may see fit.

- Create a calendar for your planner or print out a calendar template and attach it to your notebook in some way. This makes it easier for you to keep track of dates and deadlines.

- Create the daily, weekly or monthly planning sheets. You can organize your plans easily by dividing the sheets or pages into equal sections for you to write your notes . Then you can start using the notebook to plan your homework!

- Select the binder to use for your homework planner. In your selection process, consider the size of the banner. If you need a lot of space for your planning, you may choose a bigger binder. However, a smaller one is a lot easier to carry around. Therefore, considering the size is very important.

- Think about the planning method you’d like to use. You can have daily, weekly or monthly planning or to-do lists . Using a binder is a lot easier, especially in terms of adding new sections when you need them.

- Print out the homework or student planner templates you need after downloading or designing them. You can either use the templates you’ve downloaded or customize them as needed.

- Insert all of the planning sheets and dividers into your binder. As you insert these sheets, separate them using standard dividers to make it easier for you to find the different sections. Using dividers also makes it easier for you to label the different sections for better organization.

- After this, you can start using your homework planner!

Free Homework Planners

How to use your homework planner?

Sometimes it’s hard to think about how you can accomplish all of your homework when your teachers keep piling everything on as if there’s no tomorrow. But as a student, the only thing you can do is to deal with what you’re given. The best way to do this is to remain organized by using a homework planner.

Without the proper organization and time management skills, you might not be able to get the top grades you’re hoping for. Now that you know how to create a daily, monthly or weekly homework planner, here are some tips for using it:

- Select the right type of planner When you’re thinking about the type of planner to use, take your time. Select one which can accommodate all of the information you need but which still fits into your bag. Also, stay away from the store-bought ones with zippers or locks which are a challenge to open.

- Name your planner Small as this detail may be, it’s important to name your planner to remind you to keep using it. When you assign a name to an object, you’re also giving it a strong purpose in your life. Choose whatever name you want, make sure that it stands out!

- Incorporate the planner into your daily routine Make sure to bring the planner along with you at all times, especially when you go to school. Also, make sure to check the information written inside at the start and at the end of each day.

- Jot down the information ASAP As soon as your teachers assign you with homework, jot down the most important details right away. Make this a habit and it soon becomes automatic for you. Write down the assignment on your planner, the due date, and other relevant details.

- Learn how to use backward planning Whenever you write down any due date in your planner, keep going back to that homework to remind yourself that the due date is fast approaching.

- Color-coding systems work wonders Use colored dividers, stickers, papers, highlighters, and more to organize your planner. This makes it easier for you to understand and identify the information written on your planner.

- Make sure to include everything in your homework planner You must write down all the possible information in your planner, even the information about events, holidays, and other times which might take you away from doing your homework. If you don’t include this information, you can’t manage your time effectively.

- Use tabs and flags Using tabs and flags makes it easier for you to indicate due dates, finished homework, end of terms, and more. These serve as an excellent visual tool which constantly reminds you of what you need to accomplish.

- Keep the old pages and sheets in a separate file Since you’ll input everything in your planner, this means that each of the sheets contains important information. Therefore, you must keep the old pages in a separate file in case you need to use them as for reference later on.

- Congratulate yourself for creating an organizational system After creating your homework planner and following all of these tips, congratulate yourself for creating your own organizational system. As long as you stick with the planning, doing your homework becomes a lot easier.

More Templates

Graph Paper Templates

Cover Page Templates

Appointment Schedule Templates

Spelling Test Templates

Time Blocking Templates

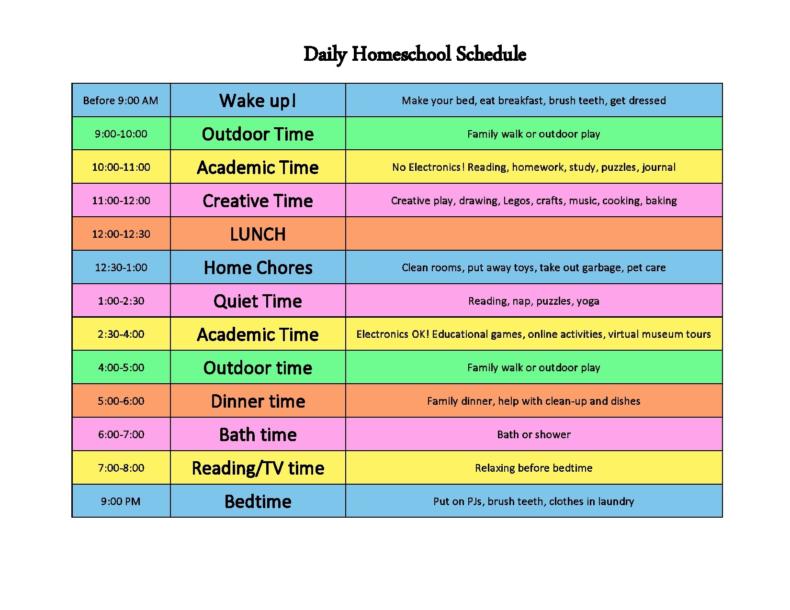

Homeschool Schedule Templates

Printable Homework Completion Chart

| Add to Folder | |

|---|---|

| creative writing | |

| children's book | |

| activities | |

| classroom tools | |

| language arts and writing | |

| vocabulary |

Featured Middle School Resources

Related Resources

EnglishForEveryone.org

Sentence correction worksheets terms of use, beginning level.

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 1

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 1 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 2

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 2 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 3

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 3 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 4

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 4 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 5

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 5 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 6

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 6 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 7

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 7 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 8

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 8 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 9

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 9 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 10

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 10 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 11

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 11 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 12

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 12 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 13

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 13 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 14

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 14 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 15

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 15 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 16

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 16 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 18

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 18 Answers

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 20

- Beginning Sentence Correction Worksheet 20 Answers

Intermediate Level

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 1

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 1 Answers

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 2

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 2 Answers

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 3

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 3 Answers

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 4

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 4 Answers

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 5

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 6 Answers

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 7

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 8 Answers

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 9

- Intermediate Sentence Correction Worksheet 9 Answers

Advanced Level

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 1

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 1 Answers

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 2

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 2 Answers

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 3

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 3 Answers

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 4

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 4 Answers

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 5

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 5 Answers

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 6

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 6 Answers

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 7

- Advanced Sentence Correction Worksheet 7 Answers

Home | About | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Homework To Do List Template

Click to See Full Template

- 3'615 Downloads

- 18 KB File Size

- January 4, 2022 Updated

- 0 Number of comments

- ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Rating

Download this template for free Get support for this template

Students often dislike thinking about homework assignments, especially, if the requirements are not clear due to poor record keeping. But homework doesn’t have to be frightening! A well organized list of what needs to get done after school makes a big difference. To help corral your scholastic activities, we offer a Homework To Do List template with priority settings, status tracking, and more.

Template Contents

Below are the worksheets included in this template.

(Homework) Start and Due Dates

A homework To Do list with columns for:

- assignments,

- priority setting,

- start date,

- status tracking,

A status summary is also available at the top right of the page.

(Homework) Completion Dates

This worksheet includes everything on the homework “Start and Due Dates” worksheet, plus an assignment “Completion” date column.

Using the Template

Personalize it.

Enter your student information (where applicable) - Term, Assigned to, and Period. You can also add a personal touch to the spreadsheet title, which comes with a standard title - “HOMEWORK TO DO LIST.” Type directly into the cell containing the standard title to overwrite it with your new title.

If there is any other information you’d like to enter at the top of the To Do list, simply insert a new row to create a new category, as shown below.

Tip: For consistency, use the “Format Painter” tool to copy the format from the rows above.

To view a how-to example, please see this short video:

https://spreadsheetpage.com/images/Homework-To-Do-List-Format-Painter-how-to.mp4

If you prefer to enter your homework To Do list by hand, delete any example assignments, and hit print - our worksheets are already formatted to print on one page.

Managing the List

Each worksheet has space for up to 50 assignments. For each assignment, you have the option to set a priority, start date, end date, completion date, and status, as well as make any notes.

Example. First 3 assignments entered.

Priority settings range from high to low. Each cell in the priority column has a dropdown list where you can choose the priority setting.

Note: If you type in an invalid entry, you will receive an error message.

Start Date and Due Date

Enter a start date and due date for each assignment. This feature of the homework To Do list will help make sure that you don’t miss any assignments, as you hold yourself accountable to complete them.

If you selected the worksheet with “Completion” date, enter the date you completed the assignment as a chronological reference.

Status tracking is another useful tool to keep focused and motivated to get assignments completed. Status options include Not Started, In Progress, Incomplete, and Complete. Make sure to use one of these 4 options from the dropdown list in each cell, in order for results to flow into the “Status Summary.”

Status Summary

The “Status Summary” shows total progress to give you a rough idea of whether or not you are on track on all your assignments.

Note: In order for an assignment to be accounted for in the status summary, it must have a status option listed in the “Status” column. We suggest pre-populating a “Not Started” status for any new assignments on the list.

Freeze Panes

By the time you scroll down to assignment #19, your column headings will disappear. To avoid this issue, use the Freeze Panes option to keep your column headings in place no matter how far down you scroll.

To freeze your column headings, click into a cell under the row displaying column headings. Next, go to the “View” menu and select the first option under the “Freeze Panes” dropdown.

Note: You must be in either “Normal” or “Page Break Preview” view to freeze panes.

To view a how-to example, see this tutorial:

https://spreadsheetpage.com/images/Homework-To-Do-List-freeze-panes-how-to.mp4

New Lists and Historical Records

You might want to have a separate homework To Do list for each subject, or you might want to save old To Do lists for reference. You can organize separate To Do lists on multiple worksheets in one file by duplicating worksheets. To duplicate a previous list, right-click on your preferred To Do list worksheet and select “Move or Copy” from the pop up menu. Next, select “Create a copy” and click “OK.”

Finally, rename new worksheets and edit, as needed.

Expand the List

The overachiever may have more than 50 assignments to tackle. In that case, expand the To Do list! Copy (Ctrl + C) the last row and “Insert Copied Cells” to create more space for the extra assignments.

Note: The print area will surpass one page once new rows are inserted.

To view a how-to example, check out this short video:

https://spreadsheetpage.com/images/Homework-To-Do-List-insert-cells-how-to.mp4

Change Color Scheme

You can modify the color schemes of your homework To Do List worksheets. To change the background color, highlight all relevant cells and use the “Fill Color” tool to select a color. To change text color, repeat these steps and use the “Font Color” tool.

Example. Change the standard green and white color scheme to purple.

How useful was this template?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 5 / 5. Vote count: 12

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this template.

We are sorry 🙁

Help us improve!

How we can improve this template?

- Helpful? Please Share.

Cancel Reply

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Live Craft Eat

homework charts

July 27, 2018 By Katie 3 Comments

Back to school brings mixed emotions in my home. For the kids, of course, it’s mostly sadness that the hazy lazy days of a hot summer have come and gone. It’s back to school and “too much homework” as they always say. For myself, as a Mom of a growing brood, there are the pros: first day of school signs and pictures, cute back to school clothes, quieter and more productive days, etc. But with the start of school, there is also the realization that I only get so many fun summers with my little ones before they want to hang out with their friends more than Mom. 😪 I also know that those clothes and supplies can cost a small fortune and with school comes endless homework, extracurricular activities, and the endless stream of paperwork and dates and times to remember for each child. Yep, definitely a mixed bag!

Of all the mixed emotions there is a constant that always seems to be a source of frustration in our home: homework. When it comes to homework I’m very, very comfortably between the tiger moms and the free-rangers, who respectively are strict disciplinarians who want sky-high academic results at all times and parents content to let their kids learn by doing and being independent as possible.

I’m not saying any of the either of the above approaches are more correct than the other, to each their own and every child needs to be parented in the way that suits them best. But I’m definitely not going to lose it if my kids miss a day of homework. Neither am I going to let them just play every day. Balance in all things is my philosophy. I’d assume most Moms rest in this cozy middle area with me. 🙂

In order to find the balance between too much and too little homework, I’ve spent some time creating homework charts, checklists, and planners for a variety of situations. ( I’ll be adding more and more over time so check back if you don’t see the one you want. Or leave a comment and I might be able to squeeze in some time to create new ones based off reader feedback.). You may also like these printable first day of school signs and bedtime routine charts too. #justsayin.

I hope one of the ones below, whether you use rewards or eschew them, works for your family and each specific child no matter what parenting style you use in your home! Just click on the text links below each preview image to download your PDF and then print your preferred hw chart for your home.

WEEKLY HOMEWORK CHARTS

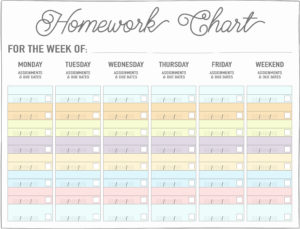

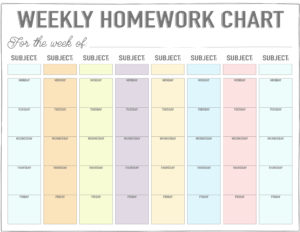

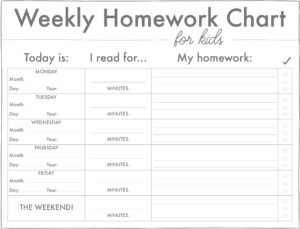

Below are a variety of weekly homework charts and planners. While they vary a little bit most of them allow some combination of assignments or class, days of the week, dates, due dates, daily reading tracking, and some form of completion in the form of a checkbox or otherwise. I hope these weekly homework planners make life easier this year!

RAINBOW WEEKLY HOMEWORK CHART

MONOCHROMATIC WEEKLY HOMEWORK CHART

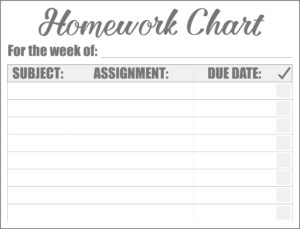

SUBJECT/ASSIGNMENT/DUE DATE/CHECKBOX HOMEWORK CHART

DAILY/WEEKLY HOMEWORK CHART

WEEKLY 8-SUBJECT HOMEWORK CHART

WEEKLY HOMEWORK CHART FOR KIDS

HOMEWORK REWARD CHARTS

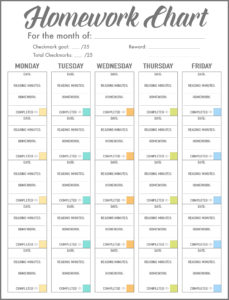

The charts below are set up for monthly tracking BUT just because they are monthly homework charts doesn’t mean you can’t set rewards at the daily or weekly level. I’ve always found it to be more effective when I tailor the rewards to each child and subject. Sometimes they need a reward on a daily basis (really struggling to form a good habit), sometimes on a weekly basis and sometimes the reward is such that they better do their homework for an entire month if I’m holding up my end of the bargain! So, whether you use these as a homework sticker chart or simply use checkmarks or something else entirely, hopefully, you’ll find a method that will work for your child! Even better if we can inspire them to love learning and the reward chart becomes a temporary aid to unlock a lifetime of learning!

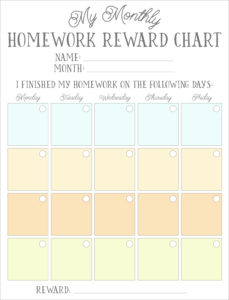

MY MONTHLY HOMEWORK REWARD CHART

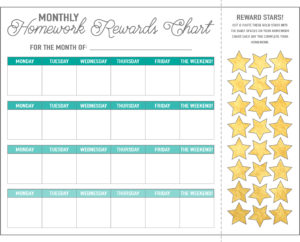

GOLD STAR HOMEWORK REWARDS CHART

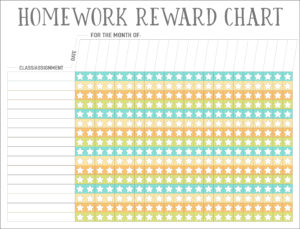

FILL-IN-THE-STARS MONTHLY HOMEWORK REWARD CHART

KIDS MONTHLY HOMEWORK LOG

KIDS HOMEWORK AND REWARD CHART

If you’re feeling generous, I’d love a re-pin (or a pin of the image below) or facebook share if you have a second. But, as always, no obligation.

Other Posts You May Like:

Reader Interactions

[…] since you’re here, don’t miss out on these free printable bedtime routine charts and homework charts/planners as things settle back into the normal day to day school routine. You also won’t want to miss […]

[…] use some of that coveted nightly free time to take requests. 🙂 Make sure you check out these printable homework charts and first day of school printables while you’re getting ready for the school […]

[…] with it so many things to keep track of – the papers! The schedules! The shopping lists! The homework and assignments! All of the meal planning for the crazy busy […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

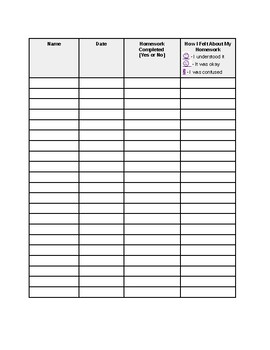

Homework Completion Sheet

- Word Document File

Description

Foster independence with this homework completion sheet. Students sign in to state whether their homework was completed, and they are able to communicate using an emoji to tell how they felt about their homework. If they struggled, this is their chance to explain that to the teacher. This works well as an artifact for Danielson for 4B, accurate record.

Questions & Answers

Teaching with mrs pickett.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

- International

- Education Jobs

- Schools directory

- Resources Education Jobs Schools directory News Search

Homework Log

Subject: Whole school

Age range: Age not applicable

Resource type: Other

Last updated

6 October 2020

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

This is an Excel spreadsheet which can allow teachers to track the completion of each individual students’ homework completion over the academic year, by inputting information into a homework log. The spreadsheet includes ten sheets (with one log on each sheet, so that ten classes can be recorded). Each homework log contains room for up to thrity-two students’ names to be added to each sheet. Six weeks has been allocated per half term with each half term/holiday clearly divided on each homework log. A key is included at the top of each homework log which can help you to record if homework was: on time, late, not done or if the student was not present/ill when the homework was set. You can also use another at the top of the homework logh which shows the quality of work/homework from 1 to 4 (1 being outstanding to 4 being poor).

I have personally utilised this Homework log to easier record when students have completed their homework by reading out names and easily colour filling each square the relevant colour. It also has the added bonus of acting as evidence for Standard 6 of the Teachers Standards by helping you to keep track of relevant data.

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

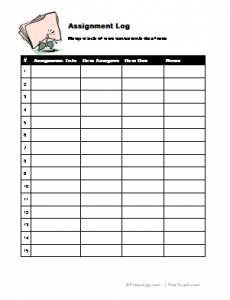

Free Worksheets and More Since 2001

- Teacher Forms

Assignment Completion Log #1

by Admin · 11 December, 2008

This log form helps students keep track of assignment due dates. For each assignment entered it has space for the assignment title, date assigned, due date and notes.

Tags: Classroom Organization Planning

- Next post Assignment Completion Log #2

- Previous post 4 Types of Sentences

- Privacy Policy

- Awards and Certificates

- Back to School

- Classroom Signs

- Coloring Pages

- Environment

- Fun and Games

- Graphic Organizers

- Journal Topics

- Telling Time

- Worksheet Creator

Coffee Fund

Thanks for the great site!! I have it saved in my favorites!

Free Homework Completion Templates For Google Sheets And Microsoft Excel

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Homework Completion, Patient Characteristics, and Symptom Change in Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD

Shannon wiltsey stirman.

a National Center for PTSD and Stanford University, 795 Willow Rd., NCPTSD, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA

Cassidy A. Gutner

b National Center for PTSD at VA Boston Healthcare System, and Boston University School of Medicine, 150 South Huntington Street. Boston, MA 02130, USA

Michael Suvak

c Psychology Department, Suffolk University, 73 Tremont Street, 8 th Floor, Boston, MA 02108, USA

d National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Street, Boston, MA 02130, USA

Amber Calloway

e National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, 150 South Huntington Street, Boston, MA 02130, USA

Patricia A. Resick

f Duke University Medical School, Durham, North Carolina 27701, USA

Associated Data

We evaluated the impact of homework completion on change in PTSD symptoms in the context of two randomized controlled trials of Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD (CPT). Female participants (n=140) diagnosed with PTSD attended at least one CPT session and were assigned homework at each session. The frequency of homework completion was assessed at the beginning of each session and PTSD symptoms were assessed every other session. Piecewise growth models were used to examine the relationship between homework completion and symptom change. CPT version (with vs without the written trauma account) did not moderate associations between homework engagement and outcomes. Greater pre-treatment PTSD symptoms predicted more Session 1 homework completion, but PTSD symptoms did not predict homework completion at other timepoints. More homework completion after Sessions 2 and 3 was associated with less change in PTSD from Session 2 to Session 4, but larger pre-to-post treatment changes in PTSD. Homework completion after Sessions 2 and 3 was associated with greater symptom change among patients who had fewer years of education. More homework completion after Sessions 8 and 9 was associated with larger subsequent decreases in PTSD. Average homework completion was not associated with client characteristics. In the second half of treatment, homework engagement was associated with less dropout. The results suggest that efforts to increase engagement in homework may facilitate symptom change.

Cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) have received extensive empirical support for a variety of mental health disorders ( Beck 2005 ). Because CBT emphasizes the development of strategies to modify problematic cognitions and behaviors, most CBT protocols emphasize the use of between-session homework as a means of practicing and solidifying new skills. Despite the central role of homework in these treatments, the nature of the relationship between homework completion and symptom change is still not well understood. Theoretically, CBT homework assignments provide clients the opportunity to practice the skills they learn in session so that they can begin to apply CBT skills in their daily lives and experience more rapid and sustained symptom relief ( Beck, 1979 ). Research on the clinical impact of homework completion has demonstrated some support for this theory, though there have been some methodological limitations to consider.

In previous research, studies comparing protocols that included homework with those that did not include homework have demonstrated larger effect sizes for protocols that included homework ( Kazantzis, Whittington, & Dattilio, 2010 ; Neimeyer & Feixas, 1990 ). Other studies on CBT for depression and anxiety have identified a relationship between homework completion and symptom reduction ( Bryant, Simons, & Thase, 1999 ; Burns & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991 ; Busch, Uebelacker, Kalibatseva, & Miller, 2010 ; Conklin & Strunk, 2015 ; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2000 ). However, some of the research on homework has been conducted with small samples that may be insufficient to detect moderation (e.g., Bryant, Simons, & Thase, 1999 , n =26;. Busch et al., n =12; Olatunji et al., n =27). Additionally, while some larger studies (e.g., Burns & Spangler, 2000 ; Burns & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991 ) have identified a positive association between homework completion and symptom improvement, most previous studies have lacked the precision required to understand the temporal relationship between homework completion and symptom change. Burns and Spangler (2000) employed structural equation modeling to examine whether CBT homework completion increased as a result of symptom change among 399 depressed clients. While this methodology represented an advance in identifying the structure of the correlation that has been observed between homework completion and symptom change, the measure used for homework completion was a single retrospective rating of overall compliance, which was assigned by clinicians towards the end of treatment. Other studies on CBT for cocaine dependence improved upon this methodology by using repeated therapist-rated assessments of the degree of homework completion for 60 patients, which was validated in some studies by observer ratings of their review of the homework in session ( Carroll, Nich, & Ball, 2005 ). However, as with previous studies, homework completion scores were aggregated across sessions, and the potential impact of prior symptom change on homework completion was not assessed. Thus, while the findings of these previous studies suggest that homework completion may precede symptom change, relatively little is known about the temporal relationship between homework completion and symptom change.

Establishing temporal precedence of a process variable is critical to understanding the nature of the relationship between that variable and a clinical outcome ( Judd & Kenny, 1981 ). Few studies to date have examined this relationship using session-to-session measures of homework completion and symptom change. Yovel and Safren (2007) did not detect a statistically significant relationship between session-to-session homework completion and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptom change, although their sample size was very small (n=16). However, Olatunji and colleagues (2015) demonstrated that CBT homework completion among 27 youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder predicted symptom change at the next session. Studies with larger samples have reported significant relationships between homework and symptom change. Strunk and colleagues (2010) demonstrated that adherence to behavioral methods and homework predicted session-to-session symptom change among 60 depressed outpatients receiving a combination of medication and cognitive therapy. Subsequently, Conklin and Strunk (2015) found that observer ratings of adherence to behavioral strategies and homework predicted session-to-session depression change ( n =53), and Schmidt and Woolaway-Bickel (2000) demonstrated that greater homework completion was associated with panic disorder symptom change in some sessions ( n =48). Thus, some evidence indicates that homework completion is associated with subsequent decreases in depression and anxiety.

Even if homework predicts symptom change, understanding the relationship between client factors, homework, and symptom change is necessary to inform treatment planning. If clients with particular characteristics are less likely to complete homework, strategies to address barriers to increase compliance may need to be integrated into treatment to optimize its effectiveness. A systematic review revealed that relatively few studies have examined whether client-level characteristics such as age, education level, or diagnostic factors predict homework completion (Scheel, Hanson, & Razzhavaikina, 2004). Those that have examined potential relationships between demographic variables and homework have studied small samples and found very few associations. For example, Bryant, Simons, and Thase (1999 ; n =25) did not find a relationship between homework completion during cognitive therapy and demographic variables or symptoms, but they did find that a higher number of prior depressive episodes predicted lower homework completion in CBT for depression. Another study found a positive association between homework completion and both age and unemployment status among individuals with panic disorder ( Schmidt & Woolaway-Bickel, 2000 ). The few other studies that have examined the relationship between symptom profiles and homework completion have generally not found an association (Scheel, Hanson, & Razzhavaikina, 2004).

There has been little research on homework in trauma-focused psychotherapy. Because avoidance is a hallmark symptom of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), engaging clients in CBT homework can represent a considerable challenge ( Reger et al., 2013 ). Whether symptom severity or client factors have an impact on homework completion that requires attention to memories, thoughts and feelings related to the trauma requires exploration. These factors inform clinical decision making about patients' appropriateness for trauma-focused treatments, with clinicians citing severity, chronicity, and perceived client ability to engage in homework as factors in deciding whether to provide trauma-focused treatments ( Cook, Dinnen, Simiola, Thompson, & Schnurr, 2014 ; Osei-Bonsu, 2016). Potential predictors of symptom change or homework engagement that have been examined in previous research ( Rizvi et al., 2009 ; Bryant, Simons, & Thase, 1999 ; Schmidt & Woolaway-Bickrel) such as education level, employment status, severity, or chronicity may predict homework engagement or moderate relationships between homework completion and symptom change. It is also important to understand whether homework completion is predictive of symptom change, rather than increasing or decreasing as symptoms decrease. If patients are not improving, they may begin to do less homework, or they may begin to work harder. Similarly, symptom improvement may motivate patients to do homework because they perceive treatment to be helping, or they might reduce the amount they do if they believe they have already experienced sufficient benefit. If higher levels of homework engagement precede symptom change, rather than resulting from it, homework completion should be prioritized in treatment, whereas the second scenario would indicate that as clients improve, their compliance with treatment may also increase.

Because homework assignments differ over the course of cognitive behavioral trauma treatments (c.f., Cooper et al., 2017 ; Resick, Monson, & Chard., 2016), examining associations of homework engagement at different time points can provide more specific information about whether and how certain types of between-session activities are associated with symptom change ( Cooper et al., 2017 ). Previous studies have found an association between assigned or completed homework and symptom change in single ( Mueser et al., 2008 , n =81) and larger, combined datasets ( Ho & Lee, 2012 , n =227), but only one PTSD study examined the temporal relationship between homework and symptom change through session-to-session analyses. In a study of Prolonged Exposure for PTSD ( n =134), higher self-reported imaginal homework adherence predicted greater symptom improvement between sessions and across treatment ( Cooper et al., 2017 ). Relationships between cognitively-oriented homework and PTSD symptom change have not yet been explored.

The current study therefore aimed to examine the temporal relationship between homework completion and session-to-session PTSD symptom change in a CBT for PTSD. Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT; Resick et al. 2008 ) is a 12-session protocol that involves the assignment of homework to promote practice of the skills taught in session. In CPT, clients are taught to challenge their beliefs and assumptions about why the trauma occurred, as well as its implications for the way they view themselves and the world. Standardized homework is assigned at each session. CPT has been shown effective for treating PTSD, with or without the assignment of written trauma accounts, across a variety of populations and demonstrated long-term benefits ( Bass et al., 2013 ; Resick et al., 2015 ; Resick, Williams, Suvak, Monson, & Gradus, 2012 ). Combined data from two randomized controlled trials of CPT ( Resick et al., 2008 ; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002 ) provides a larger sample than most previous studies, which is necessary to examine moderators of treatment outcome (LeGrange et al., 2012).

The primary goal of this study was to examine whether homework completion predicted subsequent symptom change. We hypothesized that homework completion would predict subsequent symptom change after controlling for PTSD symptoms. We also sought to explore associations between homework engagement and dropout and whether treatment condition (CPT with written trauma narrative or CPT without it) was associated with homework completion and symptom change. The second, exploratory aim was to examine demographic and diagnostic predictors of homework completion. Although important to examine for PTSD treatments, based on null findings in the research literature for other disorders (Scheel, Hanson, & Razzhavaikina, 2004), we did not expect that any specific demographic and diagnostic factors would be associated with overall homework completion. Finally, to inform future research, we examined potential patient-level moderators of the relationship between homework and symptom change, identifying potential moderators from previous studies examining associations between patient factors and homework completion or symptom change ( Bryant, Simons & Thase, 1999 ; Rizvi, Vogt, & Resick, 2009 ; Scheel, Hanson, & Razzhavaikina, 2004; Schmidt & Woolaway Bickrel, 2000 ).

Structure of CPT and Homework

Table 1 lists the homework assigned at each session, which varies in content and purpose across the course of treatment. In CPT, progressive worksheets are introduced in each session to help clients evaluate their thinking with regard to the index trauma, and each worksheet builds on previous skills and material. If homework was not completed, at least one worksheet was completed in session with therapist guidance and patients were asked to complete more for homework in addition to the newly assigned homework. While the original CPT protocol incorporated both a cognitive component and written accounts of the trauma, in a dismantling study, the cognitive-only condition demonstrated comparable improvements to the original protocol at posttreatment and 6-month follow-up, although those who were not assigned written trauma accounts improved more quickly ( Resick et al., 2008 ). Thus, it is important to examine whether differences in the homework assignments between the two treatment versions that may have accounted for differences in the trajectory of symptom change. As Table 1 indicates, in the first third of the treatments, homework centers around the use of ABC sheets to differentiate thoughts and feelings, writing an impact statement, and writing trauma narratives in the version of CPT with a written account (after sessions 3 & 4). If written narratives (e.g., impact statement or trauma accounts) were not completed for homework as assigned, they were completed verbally in session and assigned again for homework along with the appropriate worksheets. In the middle phase of treatment, new worksheets are introduced that are intended to support practice of cognitive restructuring skills; each new worksheet is assigned one session earlier in the version of CPT that does not include the written account. In the final third of treatment, the skills are combined into a single worksheet. Patients used the set of skills covered in previous sessions plus the newly introduced skill to complete each subsequent written homework assignment whether or not they had completed previously assigned homework. During the last phase of treatment (sessions 10-12), clients are also instructed to give and receive compliments and do something nice for oneself. In both studies included in this investigation, twice weekly sessions were scheduled.

| Assessment (PDS/PSS) | Timepoint/ Variable | Session | Assignment/Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT without Trauma Account | CPT with Account (if different) | |||

| 0 (baseline) | ||||

| 1 | HW1 | 1 | Impact Statement/Identify beliefs about the trauma's cause and impact | |

| HW2 | 2 | ABC Sheet/Teach clients to identify and differentiate between thoughts and feelings | ||

| HW2 | 3 | ABC sheets /Identifying thoughts and feelings | Also write trauma account & reread daily/ Facilitate emotional processing and remember the context | |

| 2 | HW3 | 4 | Challenging Questions Worksheet/Begin to challenge unhelpful or inaccurate beliefs related to the trauma | Also rewrite trauma account, reread daily; ABC Sheets |

| HW3 | 5 | Problematic Patterns of Thinking Worksheet/Identify patterns of thinking | Challenging Questions Sheet; Re-read account daily | |

| 3 | HW4 | 6 | Challenging Beliefs Worksheet (CBW) related to safety plus other worksheets on specific stuck points/Challenge trauma-related beliefs and identify more balanced ways of thinking | Problematic Patterns of Thinking Worksheet; Re-read account daily until intensity of self-blame and associated emotions diminish |

| HW4 | 7 | Read Safety Module; CBW related to module plus other CBWs on specific stuck points. | ||

| 4 | HW5 | 8 | Read Trust Module; CBW related to module plus other CBWs on specific stuck points | |

| HW5 | 9 | Read Power/Control Module; CBW related to module plus other CBWs on specific stuck points | ||

| 5 | HW6 | 10 | Read Esteem Module; CBW related to module plus CBWs on specific stuck points; Practice giving and receiving compliments daily; Do at least one nice thing for self each day/Challenge cognitions related to esteem and intimacy | |

| HW6 | 11 | Rewrite Impact Statement/Examine how beliefs about the trauma have changed; Continue to give and receive compliments and do nice things for self, Module/CBW on intimacy. | ||

| 6 | 12 | Final session: Use CBW worksheets as needed | ||

| 7 (Post-tx) | ||||

Note: HW = homework completion; PSS/PDS = PTSD Symptom Scale/Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale.

Participants

Participants were all women who consented to participate in one of two different trials of CPT ( Resick et al., 2008 ; Resick et al., 2002 ) and were assigned to CPT with or without the written trauma account. Sixty-five (78.3%) out of the 85 participants from Study 1 who were randomized to CPT, and in Study 2, 75 out of the 100 participants assigned to either CPT with ( n = 39) or without the written account ( n = 36) attended at least one session. Data from these 140 participants were used for the current study. Participants across both studies were female victims of sexual or physical violence who met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD at intake based on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS, Blake et al., 1995), with initial CAPS scores representing severe levels of PTSD symptoms ( M = 73.49, SD = 18.86). At intake, the average time since the index trauma was 12.38 years ( SD = 13.38, n = 138). The mean age of participants at intake was 34.63 years old ( SD = 11.71, n = 139). The majority of the sample was White ( n = 99; 70.7%), while 22.1% identified as African American ( n = 31). The majority of the sample was single, separated, divorce, or widowed ( n = 108, 70.1%), while a minority ( n = 32, 22.9%) were married or cohabitating. The mean years of education endorsed by participants was 14.4 ( SD = 2.69, n = 139). Treatment in this study, which was reviewed by the university's Institutional Review board, occurred in a university trauma clinic that served traumatized individuals in the St. Louis community and was delivered by masters or doctoral level clinicians who were trained to deliver CPT for the purpose of the studies (see Resick et al., 2002 ; 2008 for further details regarding recruitment, inclusion criteria, random assignment, and retention rates).

Demographic factors

Demographic variables, collected by self-report at intake, included age, years of education, race and ethnicity.

PTSD Symptom Scale (PSS; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993 )/Postraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, 1995 )

PTSD symptoms were assessed using the PSS ( Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993 ) from Study 1, and its modified version, the PDS ( Foa, 1995 ) from Study 2. Despite slightly different wording, each measure contains 17 items that correspond to the DSM-IV PTSD symptoms, yielding nearly identical scales. Participants indicate the frequency/severity of 17 symptoms in the past week on a scale from 0 = “ not at all/only one time” to 3 = “ 5 or more times per week/almost always” . A total score is obtained by summing the items. For Study 1, the average total score at pre-treatment was 29.30 ( SD = 8.75). For Study 2, the average total score at pre-treatment was 29.01 ( SD = 9.53). The PSS and PDS have demonstrated high reliability and validity and high diagnostic agreement with other clinical diagnostic measures of trauma related psychopathology ( Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997 ). In the current study, alpha coefficients were .83 and .86, respectively. These measures have been combined in previous secondary analyses (e.g. Lester, Resick, Young-Xu, & Artz, 2010 ; Stein, Dickstein, Schuster, Litz, & Resick, in press). We followed the same procedure to generate a dataset that combined the symptom scores from the two studies.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; (Beck, Ward, Mendelsohn, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961)/Beck Depression Inventory—II (BDI–II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996 )

The BDI (Beck, Ward, Mendelsohn, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) was used to assess depression symptoms for Study 1 and the BDI-II ( Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996 ) for Study 2. Both measures contain 21-items assessing depressive symptoms and have been widely used with good reliability and validity ( Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996 ). Coefficient alpha for the studies were .92 for the treatment study and .91 for the dismantling study. Scores on these measures were standardized prior to combining.

Assessment of Homework Completion

The homework review form assessed how often clients worked on or reviewed homework materials between sessions. For each homework assignment, clients indicated the frequency of homework completion using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all”, 2 = “less than 2 times”, 3 = “2-5 times”, 4 = “6-10 times”, 5 = “more than 10 times”). Clients and therapists completed the homework review sheet together before each session, using the number of worksheets and other materials that the client completed to corroborate their assessment of the frequency of their homework completion. Use of homework assignments between each assessment point (every other session) were averaged to generate a homework variable for each time period (“HW”) in the current analyses.

Clients completed the PSS/PDS and BDI/BDI-II at baseline, prior to sessions 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, and post-treatment. The homework completion form was completed by the therapist and client together at the beginning of each session. Observer ratings of fidelity were conducted on a randomly selected subset of sessions and indicated that the homework review procedures and forms were completed in 100% of the sessions that were rated.

Data Analyses

Our primary goal was to examine the association between homework completion during a particular week on subsequent changes in PTSD symptoms from that point in treatment through the post-treatment assessment, and to determine whether this differed based on whether patients received the version of CPT that included the trauma account. To accomplish this goal, we evaluated a series of piecewise growth models conducted using multilevel regression (Singer & Willett, 2003) with the Mplus software package (Version 7; Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012). A piecewise growth model breaks an overall trajectory into multiple distinct phases. The focus of the current manuscript investigated change over time during treatment following the week during which homework was assessed. We conducted piecewise growth modeling (as opposed to only including data points following homework assessment) because the piecewise regression approach uses all of the information available for each participant (before and after the session of interest) to produce the most accurate and powerful estimates of subsequent change.

The right side of Table 2 depicts the time variables that were used in the piecewise models. With the exception of the first phase, between baseline and session 2, two sessions and homework assignments were completed between PTSD symptom assessment points. Thus, Table 2 shows that time was modeled as session number increasing by two from one assessment to the next, with the exception of an increase in one from session 12 to post-treatment. Two time variables were entered as Level-1 (within participants) predictors of PTSD symptoms in each piecewise model. The first time variable was described above and centered (or zeroed) at the second session of each assessment phase. As shown in Table 2 , the remaining time variables were modeled as recommended by Singer & Willet (2003).

| Session | Intercept | Subsequent ΔPTSD | Time Variables | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. (95% CI) | Est. (95% CI) | S2 | S2_PST | S4 | S4_PST | S6 | S6_PST | S8 | S8_PST | S10 | S10_PST | S12 | S12_PST | |

| 0 | -2 | -2 | -4 | -4 | -6 | -6 | -8 | -8 | -10 | -10 | -12 | -12 | ||

| 2 | 27.65(26.29, 29.02) | -18.57(-20.23, -16.91) | 0 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -4 | -4 | -6 | -6 | -8 | -8 | -10 | -10 |

| 4 | 24.52(23.02, 26.01) | -15.52(-17.12, -13.91) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -4 | -4 | -6 | -6 | -8 | -8 |

| 6 | 20.91(19.29, 22.52) | -11.65(-13.16, -10.14) | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -4 | -4 | -6 | -6 |

| 8 | 17.43(15.73, 19.13) | -7.91(-9.33, -6.49) | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -4 | -4 |

| 10 | 14.01(12.29, 15.72) | -4.16(-5.38, -2.95) | 8 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -2 |

| 12 | 10.47(8.76, 12.18) | 0.17(-0.96, 1.30) | 10 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 11 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

Note. Time Variables = the time variables used for the regression analysis at each assessment; S = session number, _PST = the second time coefficient; Est. = estimate; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; ΔPTSD = change in PTSD. Intercept corresponds to the level of PTSD at that assessment.

Three time coefficients were produced from these piecewise models. The intercept term estimated PTSD symptoms assessed prior to the second session of the phase in which homework was assessed (the assessment for which both time variables were equal to zero in Table 2 ), the coefficient for the first time variable produced an estimate in change in PTSD from that session to post-treatment, and the coefficient for the second time variable represented the difference in rate of change prior to and after the session. The intercept and coefficient for the first time variable were of most interest to the current analyses. To evaluate the impact of homework on subsequent change in PTSD symptoms, homework completion was entered as a Level-2 predictor of each change coefficient, and the primary coefficient of interest was the Homework × time variable interaction, which assessed the impact of homework during that phase (the two sessions between assessment points) on subsequent changes in PTSD symptoms through post-treatment. To evaluate the impact of treatment condition (CPT with or without the trauma account) on the homework effect on subsequent change in PTSD, we added a treatment condition variable and a treatment condition × homework interaction (product) term as Level-2 predictors of each time coefficient. We then conducted a logistic regression analyses with treatment dropout status (0,1) regressed on homework scores to evaluate the relationship between homework and dropout.

For our exploratory analyses, we examined zero-order correlations between patient characteristics and homework completion to determine whether certain characteristics predicted the amount of homework that patients complete. We next conducted exploratory analyses that included patient characteristics that might moderate the relationship between homework completion and symptom change as Level-2 predictors in the piecewise models described above.

Homework and Treatment Outcome

The left side of Table 2 reports the model-derived estimates for PTSD levels and subsequent change in PTSD for each time point. Table 3 reports the coefficients for estimates of the impact of homework completion on the level of PTSD at each assessment point (i.e., impact on the intercept of the piecewise models) and impact of HW on subsequent change on PTSD. Significant effects of homework emerged at two sessions, as described below. The extent to which patients completed the homework assigned in Sessions 2 and 3 (HW2; when ABC worksheets are assigned to help the patient identify and differentiate between thoughts and feelings and at session 3 when first written account or focusing all of the ABC worksheets on the worst traumatic event is assigned) was related to both PTSD levels at Session 4 and subsequent changes from Session 4 to post-treatment. Participants who scored a zero (lowest score) on homework completion during these sessions on average exhibited a 7.24 ( d = -.82) decrease in PTSD symptoms from Session 4 to post treatment, while people who scored a five (highest score) exhibited a 22.49 ( d = -2.55) decrease in PTSD symptoms during this time period.

| Homework by Time Interactions (Combined Sample) | Written Account by Homework Interaction (Moderator Analysis) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | |||||||||

| bHW1→S2 | 139 | 1.38 | 1.51 | .132 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.20 | .842 | 0.03 |

| HW1→ΔS2-PST | 0.03 | 0.31 | .758 | 0.05 | -0.27 | -1.33 | .183 | -0.23 | |

| HW2→S4 | 136 | -2.48 | -1.15 | .251 | -0.20 | ||||

| HW2→ΔS4-PST | -0.18 | -0.65 | .517 | -0.11 | |||||

| HW3→S6 | 128 | 1.95 | 1.83 | .068 | 0.32 | -3.99 | -1.63 | .104 | -0.29 |

| HW3→ΔS6-PST | -0.27 | -1.79 | .074 | -0.32 | 0.49 | 1.56 | .120 | 0.27 | |

| HW4→S8 | 119 | 1.26 | 0.68 | .496 | 0.12 | -5.31 | -1.37 | .170 | -0.25 |

| HW4→ΔS8-PST | 0.07 | 0.23 | .820 | 0.04 | -0.43 | -0.74 | .457 | -0.14 | |

| HW5→S10 | 119 | 1.26 | 1.32 | .187 | 0.24 | -0.17 | -0.07 | .946 | -0.01 |

| HW5→ΔS10-PST | 0.18 | 0.29 | .774 | 0.05 | |||||

| HW6→S12 | 89 | -0.59 | -0.33 | .739 | -0.07 | -3.76 | -1.01 | .313 | -0.21 |

| HW6→ΔS12-PST | -0.37 | -0.37 | .712 | -0.08 | -0.59 | -0.26 | .795 | -0.06 | |

Note. Results on the left side indicate findings for the entire sample, homework by time interaction. Analyses represented on the right side included an interaction between time and a variable indicating whether or not the trauma account was assigned. HW = homework completion, S = session, n = sample size for that analysis, CR = critical ratio ( b /standard error of b, which follows a z -distribution), p = p -value, d = effect size estimate calculated using d = 2 CR n , with .20, .50, and .80 indicating the cutoffs for small, medium, and large effect sizes. The Level-1 regression equation for the analysis was Y ij = b o + b 1 Time1 + b 2 Time2 + r ij , where Y ij = PTSD symptoms for participant at assessment i for participant j, b o = the regression intercept (PTSD levels at that session); b 1 Time1 = Change in PTSD from that session to the posttreatment assessment; PTSD Time2 = the difference in rate of change in PTSD before and after the session, and r ij = the level-1 residual. All of these terms as well as homework use × time parameters interactions were included in the model. However, to facilitate interpretation of the results, only the parameters representing the impact of HW on PTSD levels and subsequent change are presented on the left, and the main effects of Time, HW, and the moderator, as well as all two way and three way interactions were included in the model reported on the right. Coefficients for the entire model can be obtained from the authors.

Figure 1 shows that participants who completed more homework during the HW2 phase, comprising Sessions 2 and 3 of treatment, initially exhibited higher PTSD levels at Session 4 and experienced larger subsequent decreases in PTSD relative to participants who completed less homework that was assigned in Sessions 2 and 3. Mplus allows intercepts and slopes to be modeled as predictors or outcomes at Level-2. Because homework completion during the phase comprising Sessions 2 and 3 was associated with higher Session 4 PTSD symptom levels, but larger decreases in PTSD symptoms, we evaluated a model with the two time coefficients regressed on the Level-1 intercept (which represented PTSD levels at Session 4) to evaluate change over time when controlling for Session 4 PTSD levels. In this model, the impact of homework after Sessions 2 and 3 on subsequent PTSD approached statistical significance ( b = -0.21, CR = -1.86, p = 0.063, d = -0.32). Thus, the larger decrease in PTSD symptoms exhibited from Session 4 to post-treatment by participants who completed more homework at Sessions 2 and 3 relative to those who completed less homework was largely accounted for by differences in PTSD symptoms prior to Session 4. Participants who completed more homework during this phase had exhibited more PTSD symptoms prior to Session 4 than participants who completed less homework assigned in Sessions 2 and 3. Participants who completed more homework during this phase also exhibited larger decreases from Session 4 to post-treatment. While completion of homework assigned in Sessions 2 and 3 was not associated with post-treatment PTSD scores, patients who were scoring higher in symptoms prior to Session 4 and did more homework at Sessions 2 and 3 were able to catch up to their counterparts who were experiencing lower symptoms during this earlier phase of treatment.

The impact of sessions 2 and 3 homework: a) overall, b) at high levels of years of education, and c) at low levels of years of education. HW2 = Homework completion for sessions 2 and 3

The amount of homework completed during the phase comprising Sessions 8 and 9 (when Challenging Beliefs worksheets, which guide the patient in challenging their beliefs and identifying more adaptive beliefs, and modules on Trust and Power and Control are assigned) also predicted subsequent changes in PTSD symptoms. Participants who scored a zero (lowest score) on homework use during this time period on average exhibited a .01 ( d < -.01) decrease in PTSD symptoms from Session 10 to post treatment, while people who scored a 3.75 (highest score) exhibited a 5.93 ( d = -.49) decrease in PTSD symptoms during this time period. However, as indicated in Table 4 , the amount of homework completed after Sessions 8 and 9 was not associated with Session 12 PTSD symptoms, and when controlling for Session 10 PTSD symptoms, the impact of homework completion on symptom change over the remainder of the protocol remained significant ( b = -0.56, CR = -2.134, p = 0.033, d = -0.39). While on average, participants who completed more homework assigned in Sessions 8 and 9 reported fewer PTSD symptoms at post-treatment, the effect was small, and this difference did not approach statistical significance ( b = -0.74, CR = -1.027, p = 0.471, d = -0.13).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | n | M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Age | --- | 139 | 34.63 (11.71) | |||||||||||

| 2 Years of Education | .08 | --- | 139 | 14.4 (2.69) | ||||||||||

| 3 Months Since Rape | .57 | .11 | --- | 138 | 148.63 (160.52) | |||||||||

| 4 Minority Status | .08 | -.01 | .21 | --- | 140 | 0.29 (0.46) | ||||||||

| 5 Pre-Treatment PTSD symptoms | -.11 | -.02 | -.15 | -.07 | --- | 139 | 29.58 (8.93) | |||||||

| 6 Pre-Treatment Depression symptoms | .09 | -.09 | .01 | -.09 | .50 | --- | 138 | 26.04 (10.97) | ||||||

| 7 HW1 (session 1) | .01 | -.06 | .05 | .03 | .20 | .22 | --- | 139 | 3.16 (0.86) | |||||

| 8 HW2 (sessions 2 and 3) | -.12 | .21 | -.11 | -.06 | .15 | -.04 | .13 | --- | 136 | 2.69 (0.94) | ||||

| 9 HW3 (sessions 4 and 5) | -.04 | .03 | -.02 | -.06 | .05 | -.01 | .03 | .53 | --- | 128 | 2.03 (0.86) | |||

| 10 HW4 (sessions 6 and 7) | .15 | -.03 | .14 | .04 | .03 | .04 | .22 | .03 | .14 | --- | 119 | 2.34 (0.49) | ||

| 11 HW5 (sessions 8 and 9) | -.08 | .05 | -.13 | -.14 | -.10 | -.13 | -.12 | .64 | .65 | -.08 | --- | 119 | 1.91 (0.92) | |

| 12 HW6 (session 10 and 11) | -.04 | .28 | -.22 | -.09 | .12 | -.06 | -.12 | .65 | .66 | .18 | .65 | --- | 89 | 2.15 (0.81) |

| 13 Average HW Use | -.11 | .03 | -.14 | -.04 | .16 | .04 | .39 | .77 | .80 | .30 | .77 | .81 | 140 | 2.47 (0.64) |

PSS/PDS = PTSD Symptom Scale/Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; HW = homework completion; n = sample size; M = mean; SD = standard deviation. Because some data were missing in the original data set, sample sizes are noted with descriptive statistics.

The righthand side of Table 3 presents results of a moderator analysis to determine whether treatment version (CPT with or without the account) was associated with symptom change. Treatment version did not moderate the relationship between homework and symptom change. This held true even during the time periods when the trauma account would have been assigned, completed, and reviewed (HW2 and HW3) or at the subsequent assessment period, when worksheet assignments between the two versions of the treatment (as described in Table 1 ).

We next conducted a series of logistic regression analyses examining HW as a predictor of whether or not participants dropped out of treatment. Twenty-five (18.0%) of the 139 participants with data for Session 1 (HW1) dropped out of treatment. HW1 did not significantly predict dropout status ( b = .35, CR = 1.39, p = .165, OR 1 = 1.41, OR/SD = 1.65). HW2 (Session 2 and 3, b = -.20, CR = -.78, p = .438, OR = .82, OR/SD = .88) and HW3 (Session 4 and 5, b = .23, CR = .67, p = .501, OR = 1.25, OR/SD = 1.46) scores also did not significantly predict treatment dropout. Five (4.2%) of the 119 participants who had HW4 scores available dropped out of treatment. HW4 (Session 6 and 7) homework scores predicted dropout ( b = -2.96, CR = -2.43, p = .015, OR = .05, OR/SD = .10) such that a one SD increase in homework completion was associated with a 9.55 times decrease in the likelihood of dropping out. Similarly, six (5%) of the 119 participants who had HW5 scores available dropped out of treatment with HW5 (sessions 8 and 9) scores inversely related to dropout ( b = -1.43, CR = -2.69, p = .007, OR = .24, OR/SD = .26) such that a one SD increase in homework completion was associated with a 3.82 times decrease in the likelihood of dropping out. Only four (4.5%) of 89 participants with HW6 (session 10-11) scores available dropped out of treatment. The association between HW6 and dropout approached statistical significance ( b = -4.47, CR = -1.69, p = .090, OR = .01, OR/SD = .01). However the odds ratios were quite small and indicated a one SD increase in homework completion was associated with at 72.89 times decrease in the likelihood of dropping out, suggesting the failure to reach statistical significance may have been due having such a small number of dropouts during this phase.

Relationship between baseline characteristics, homework completion, and symptom change

Table 4 displays zero-order correlations among demographic variables, initial PTSD symptom levels, and the HW variables between each PTSD assessment point, as well as descriptive statistics for these variables. The scores indicate that on average, clients endorsed doing homework either less than two times or two to five times between sessions, which were scheduled twice per week. As indicated in Table 4 , the initial PTSD scores were positively correlated with HW1 (Session 1; r = .20, p = .016), such that those endorsing higher initial PTSD symptoms reported completing the first homework assignment more frequently. Initial depression scores were positively correlated with HW1 (Session 1) in the same manner; r = .20, p = .011. Number of years of education was significantly, positively associated with completion of homework assigned in Sessions 3 and 4 (HW2; r = .21, p = .015) and Sessions 10 and 11 (HW6; r = .28, p = .008). Number of years since the index trauma was negatively associated with HW6 ( r = -.22, p = .044). Average homework completion did not correlate with any other demographic or baseline variable. The supplemental table summarizes the findings of the exploratory analyses examining moderators of the impact of homework on changes in PTSD. Only one significant moderator by homework interaction emerged, that of years of education and completion of homework assigned after Sessions 2 and 3 (HW2). Figure 1b and 1c shows that completion of the homework assigned in Sessions 2 and 3 was associated with better outcomes for patients with fewer years of formal education compared to those who endorsed more years of education.

With data from two clinical trials of CPT, this study examined the association between homework completion and symptom change in a cognitive behavioral therapy. We employed a session-to-session measure of homework completion to investigate the relationship between specific homework activities and subsequent symptom change. We found some support for the hypothesis that homework completion is associated with greater overall symptom change, with homework engagement at certain timepoints associated with subsequent symptom change. Whether patients received the version of CPT that included a written trauma account or the version that did not include the account, did not appear to moderate the association between homework completion and symptom change at any timepoint in the treatment. Our results regarding the relationship between homework completion and subsequent dropout also suggested that homework completion in the latter half of treatment may be a good indicator of treatment engagement as patients who completed more homework were less likely to drop out. Finally, we found evidence that while certain client characteristics were associated with early homework completion, they do not predict overall engagement in homework. For the most part, they did not moderate the relationship between homework completion and treatment outcomes, with one exception (years of education).

More frequent completion of homework assigned in Sessions 2 and 3 was associated with smaller short-term decreases in PTSD symptoms at Session 4 regardless of whether the trauma account was assigned in Session 3. However, homework completion during this time period predicted greater symptom change over the course of treatment. While this may have been because in part there was more room for improvement among those who completed more homework, it suggests that those with higher symptoms in Sessions 2 and 3 may be able to “catch up” to those with lower symptoms by completing more homework. In both forms of the treatment (with and without the trauma account), homework assignments in these early sessions require attention to the index trauma and identification of associated thoughts and feelings. While the decreases in avoidance required to do this work may initially reduce the amount of symptom change that patients experience, or even occasionally result in a transient increase in symptoms (Larsen, Stirman, Smith, & Resick, 2016), working on the traumatic event between sessions ultimately appears to be beneficial. These findings suggest that clients, especially those who are experiencing less improvement in early sessions, should be encouraged to complete more homework during these sessions, and reassured that doing so, even if challenging in the short-term, is associated with better longer-term results.