Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 7, Issue 9

- Protocol for a qualitative study exploring perspectives on the INternational CLassification of Diseases (11th revision); Using lived experience to improve mental health Diagnosis in NHS England: INCLUDE study

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Corinna Hackmann 1 ,

- Amanda Green 1 ,

- Caitlin Notley 2 ,

- Amorette Perkins 1 ,

- Geoffrey M Reed 3 ,

- Joseph Ridler 1 ,

- Jon Wilson 1 , 2 ,

- Tom Shakespeare 2

- 1 Department of Research and Development , Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Hellesdon Hospital , Norwich , UK

- 2 Department of Clinical Psychology , Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia , Norwich , UK

- 3 Department of Psychiatry , Global Mental Health Program, Columbia University Medical Centre , New York , New York , USA

- Correspondence to Dr Corinna Hackmann; Corinna.hackmann{at}nsft.nhs.uk

Introduction Developed in dialogue with WHO, this research aims to incorporate lived experience and views in the refinement of the International Classification of Diseases Mental and Behavioural Disorders 11th Revision (ICD-11). The validity and clinical utility of psychiatric diagnostic systems has been questioned by both service users and clinicians, as not all aspects reflect their lived experience or are user friendly. This is critical as evidence suggests that diagnosis can impact service user experience, identity, service use and outcomes. Feedback and recommendations from service users and clinicians should help minimise the potential for unintended negative consequences and improve the accuracy, validity and clinical utility of the ICD-11.

Methods and analysis The name INCLUDE reflects the value of expertise by experience as all aspects of the proposed study are co-produced. Feedback on the planned criteria for the ICD-11 will be sought through focus groups with service users and clinicians. The data from these groups will be coded and inductively analysed using a thematic analysis approach. Findings from this will be used to form the basis of co-produced recommendations for the ICD-11. Two service user focus groups will be conducted for each of these diagnoses: Personality Disorder, Bipolar I Disorder, Schizophrenia, Depressive Disorder and Generalised Anxiety Disorder. There will be four focus groups with clinicians (psychiatrists, general practitioners and clinical psychologists).

Ethics and dissemination This study has received ethical approval from the Coventry and Warwickshire HRA Research Ethics Committee (16/WM/0479). The output for the project will be recommendations that reflect the views and experiences of experts by experience (service users and clinicians). The findings will be disseminated via conferences and peer-reviewed publications. As the ICD is an international tool, the aim is for the methodology to be internationally disseminated for replication by other groups.

Trial registration number ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03131505 .

- International Classification of Diseases

- Personality Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018399

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study is the first to gather expert by experience views on the proposed criteria to be fed into the revision process of the International Classification of Diseases.

All aspects of the proposed study have been co-produced with experts by experience and agreed with a representative from WHO.

Qualitative focus group data will be thematically analysed to form the basis of co-produced recommendations to be fed back to WHO.

The themes and resulting recommendations will be limited to five diagnostic categories and will only reflect views from the UK.

Introduction

Diagnostic systems have a number of functions both from the perspective of the clinician and service user. 1–3 Diagnosis offers indications for treatment, may guide expectation regarding prognosis and can help people to make sense of their experiences of living with mental health (MH) difficulties. 1 2 In order for a diagnostic system to be useful, it is critical that it reflects the day-to-day experiences of people living with the symptoms. Service users have reported relief derived from diagnostic definitions that resonate with and explain their experiences. 1 4 On the other hand, some feel their diagnosis does not ‘fit’ with or describe their experiences, and thus has limited utility other than being a ‘tick box’ exercise of labelling and categorising. 5–7 To date, it appears that no revision of the major systems for psychiatric diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) has sought feedback from service users prior to publication.

Diagnostic systems are designed for clinicians; despite this, service users can easily access the diagnostic criteria. Research shows that the labels, language and descriptions used in these systems can impact people’s self-perception, their interpretations of how other people view them and their understanding of the implications of having a diagnosis, including the prognosis and potential for recovery. 5 8 9 These interpretations can have a direct impact on factors such as self-worth and self-stigmatisation, social and occupational functioning, recovery and service use. 5 6 10 For example, service users have reported that terms like ‘disorder’ and ‘enduring’ suggest permanency, impeding their hope for recovery. 5 Similarly, others have reported that the descriptions and terms used in diagnostic systems (eg, language like ‘deviant’, ‘incompetent’, ‘disregard for social obligations’ and ‘limited capacity’) can be stigmatising and unhelpful, leading to feelings of rejection, anger and possible avoidance of services. 5 6 8 Clarity on the perceptions of individuals receiving a diagnosis, in terms of the language, meaning and implications of what is included in the system, may help to minimise possible negative consequences.

Evidence suggests that clinicians also have concerns regarding the validity and clinical utility of the current diagnostic systems. 3 11–13 For instance, health professionals have reported that some diagnostic definitions feel arbitrary, artificial or unreflective of the typical presentations they observe in practice. 11 12 Other evidence suggests that clinicians find the categories difficult to use, particularly for distinguishing between disorders. 9 12 14 Clinicians have also expressed reservations regarding the terminology and associated stigma, particularly for conditions such as Schizophrenia and Personality Disorder. 13 15 These findings are from studies that have been conducted after the criteria have been released. Prospective input from clinicians on the proposed criteria as part of the process of revision may therefore improve the validity and clinical utility of diagnostic systems.

The value of expertise by experience is increasingly recognised by policymakers, 16–18 service providers and researchers. 19 20 Many have argued that processes of diagnosis could be improved by including perspectives of those with lived experience. 10 21 It has been suggested that within the diagnostic categories, "the traditional language is useful for listing and sorting but not for living and experiencing. ‘Naming' a thing is not the same as 'knowing'a thing" (p90) 22 and therefore categories could be improved by viewing service users as ‘authors of knowledge from whom others have something to learn’ (p291). 21 Likewise, it has been argued that diagnostic systems could be improved by addressing problems identified by practising clinicians. 3

Input regarding the proposed content for the ICD-11 from service users and clinicians should be used to support the process of revision and improvement. Feedback and clarity from service users on (1) whether the content of the system is in line with their experience of symptoms and (2) their interpretations of the content and language should facilitate the development of a system that is more accurate and valid, with minimised unintended negative impact.

Aims and objectives

This research project will use a focus group methodology to ask service users and clinicians who use the ICD diagnostic tool (psychiatrists and general practitioners) their views on the proposed content for the ICD-11. Data collected through collaborative discussion in the groups will be inductively analysed, and resulting themes will be triangulated with an advisory group (involving additional service users and clinicians). The output will be recommendations for improvement to ICD-11 content that have been co-produced with a feedback group (of different service users and clinicians).

Research questions

What are the views and perspectives of service users and clinicians on the content of the ICD-11?

How could the system be improved for the benefit of service users and clinicians?

Methods and analysis

Study design.

This is a qualitative study. Data will be collected through focus groups. Focus groups are an appropriate method of data collection to answer the study research questions seeking to explore views and perspectives of service users and clinicians, where our analysis will aim to define key themes and points of consensus or divergence gathered through interaction, 23 24 drawing on participants own perspectives and choice of language. 25 Participants will be given a copy of the proposed diagnostic criteria relevant to their diagnosis to discuss in the group. This will include both the technical version (as it is proposed for the ICD-11) and a lay translation of the criteria. Thematic analysis 26–28 will be used to identify emergent recurring and/or salient themes in the focus group data. The themes will form the basis for co-produced recommendations to support the development of the ICD-11. Data collection for this study commenced in February 2017 and analyses are planned to be completed and fed back to WHO by the end of December 2017.

Co-production

The research team that developed this project includes a service user expert by experience (AG), two academics (TS, CN), two research clinicians (a consultant psychiatrist (JW) and a clinical psychologist (CH)) and two research assistant psychologists (AP, JR). A service user expert by experience research team member will be involved in all aspects of the research, including design, facilitating focus groups, analysis, write-up and dissemination.

In developing the project, team members consulted a local service user governor, service users and the service user involvement leads at the hosting National Health Service organisation. This input helped shape the design (changing and broadening the process of recruitment of service users and supporting the use of focus groups) and the initial selection of the diagnoses that were included.

Co-production with service users, clinicians and researchers will continue throughout the project. Data analysis will be co-produced through involvement of the service user expert by experience on the research team and the advisory and feedback groups.

Diagnoses under investigation

With agreement from WHO, five diagnoses have been selected for exploration: Personality Disorder, Bipolar I Disorder, Schizophrenia, Depressive Disorder and Generalised Anxiety Disorder. These diagnoses include a wide range of symptom phenomena. Personality Disorder, Bipolar I Disorder and Schizophrenia are found to be more stigmatised, rejected and negatively viewed than other diagnoses, meaning they may have a particularly negative impact and be more consistently associated with harm. 29 30 Depressive Disorder and Generalised Anxiety Disorder are highly prevalent, making the largest contribution to the burden of disease in middle-income and high-income countries, including the UK. 31

Lay translation

The lay translations of the criteria have been produced by members of the research team including psychiatrists and other clinicians, and approved by a representative from WHO to ensure they reflect the proposed ICD-11. Documents have been created presenting lay translations alongside the technical version as it is written in the ICD-11, so that participants are easily able to refer to either source. Copies of these are available in English for researchers wishing to replicate this study.

Recruitment

Sampling will be purposive and include a number of pathways to ensure maximum inclusivity. Recruitment of service users will be both via clinicians in a MH trust and self-referral via a number of routes. Promotion of the study will be via clinicians, service user involvement leads in a MH trust and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Clinicians in the MH trust will be asked to identify potential participants and seek consent to be contacted by the research team. Service user involvement leads will disseminate information about the study to service users and the membership of a MH trust (which includes many previous service users), providing a telephone number and email address to self-refer if interested. NGOs will promote the study using the same materials. The study will be promoted through recruitment posters, service user involvement forums and on social media. Clinicians will be recruited via team leaders, word of mouth and email communications promoting the project.

Once self-referral or consent to contact has been established, a member of the research team will make contact, provide potential participants with a brief overview of the study, and answer any questions. If the individual wishes to be involved in the study, they will be sent a copy of the participant information sheet via post or email. This information sheet outlines the purpose and nature of the study, and the ethical safeguards regarding data protection and privacy. Potential participants will have at least 72 hours to consider whether they would like to be involved in the study. If the individual would like to take part in the study, researchers will arrange to meet them at least 1 week before the focus group to complete the consent process and give them the relevant proposed diagnostic criteria to read and consider.

Sample size

There will be two service user focus groups for each of the five diagnoses. Additionally, there will be four clinician focus groups. The ICD system is primarily used by medical doctors in the UK, although clinical psychologists have been included in this study as they also apply the system in their work. 32 In this study, the diagnostic criteria presented to participants are divided into distinct discussion points. During the focus groups, these discussion points will be addressed one by one and participants will be asked for their feedback through predefined questions and prompts. This includes asking people their views of the proposed features, the language used, the positives and negatives of what is included and how the classification might be improved for the benefit of service users. In light of this, the number of groups was agreed based on research stating that using more standardised interviews decreases variability and thus requires fewer focus groups. 33 In total, there will be 14 groups, containing three to six participants each. This will give a total sample of 42–84 participants (30–60 service users and 12–24 clinicians). The advisory group will comprise three to five additional service users and three clinicians. Lastly, the feedback group will comprise five service users and three clinicians. The focus group size was chosen to allow participants opportunity to discuss their views and experiences in detail, while increasing recruitment feasibility. 34 The sample size should be sufficient in providing data to meet the aims and to cover a range of views. Evidence suggests that the majority of themes are discovered in the first two to three focus groups. 35

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adult service users (18 years and older) may be included in the focus groups if they have formally received at least one of the five diagnoses under investigation and have accessed services within the last 5 years (including those currently in receipt of services). People with multiple diagnoses may only take part in one focus group, but will be given the option of which group. Clinicians will have had experience working in MH, including the use of the psychiatric diagnoses under investigation. Individuals may only participate in either one focus group, the advisory group or the feedback group.

Individuals will be excluded if they are under the age of 18 years, lack the capacity to consent, or have an inability to speak fluent English (as fluent English is required to participate in the focus groups). Individuals will also be excluded if their participation is deemed unsafe to themselves or others by their lead clinician or clinicians on the research team.

Data collection

Focus groups are the most applicable method for data collection to meet our research aims, as attitudes, opinions and beliefs are more likely to be revealed in the reflective process facilitated by the social interaction that a focus group entails than by other methods. 23–25 Additionally, focus groups have proved to be a useful way of exploring stigma issues in MH, 36 and service users are often familiar with group settings for discussing MH issues.

The summary of the new diagnostic guidelines and lay translation will enable participants to reflect on both the content and the language of the proposed criteria. During the groups, topic guides will encourage participants to discuss and share views of the relevant diagnostic category. This includes their overarching views, thoughts and feelings; as well as, specific reflections on areas such as the language used, aspects that may be helpful or unhelpful, and suggestions for improvement.

Each focus group will be led by an experienced and trained member of the research team and have an assistant facilitator. Service user focus groups will last 60–90 min, and clinician focus groups will last 2–2.5 hours to account for the discussion of multiple diagnoses.

The focus groups will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts will first be read and descriptively openly coded (using the same language as participants where possible) by the lead researcher. Approximately 25% of the transcripts will be independently open coded by another member of the research team, as a validity check. Codes will be compared and discussed until consensus is reached. The five diagnoses will initially be analysed separately to produce themes that are relevant to each diagnosis. Following this, these themes will be compared with identify common themes relevant to all the diagnostic categories. Analysis of data will mainly be descriptive. We will take a critical realist epistemological stance to analysis, recognising that there are multiple individual realities, but taking a pragmatic approach to analysing data at face value, drawing on the perspectives of individuals as they choose to represent themselves through discussion. 37 Thematic analysis will be used to inductively code themes that reoccur or appear important. 26–28 The concept of salience will be referred to here, to guide coding that is conceptually and inherently significant, not just frequently occurring. A qualitative data management software system (NVIVO-11) will be used to facilitate data analysis.

In addition to descriptive data for thematic coding, focus groups generate data that is conversational. Analysis of this requires an inductive approach that focuses on instances in the data where there is marked agreement (consensus), disagreement or divergence. These instances will be identified as ‘critical moments’. The sample size is small and purposive. Consequently, summary quantified coding matrices will not be produced. Instead there will be a focus on the 'critical moments' to direct the analysis and eventual findings, reporting on the issues that are of central importance to the participants.

Following analysis of each focus group, a second stage analysis will be conducted to compare and contrast findings across groups. The analysis will seek out consensus, disagreement and inconsistency within service user and clinician focus groups, and between diagnoses. This second stage analysis will involve discussions within the research team to refine the themes and to develop higher level themes, that is, grouping the open codes into meaningful conceptual categories. This will allow tentative conclusions to be drawn about aspects of the diagnostic criteria which may be particularly pertinent for some groups and less important for others. It will also enable conclusions to be drawn regarding generic language or overall responses to the diagnostic criteria, in comparison to more nuanced reactions to diagnostically specific categories.

The output from the analysis will be higher level themes and categories that form the basis of recommendations for the ICD-11. These themes will be triangulated with the advisory group. The resulting themes will be discussed with the feedback group in order to co-produce the recommendations. These recommendations will be contextualised with a description of the themes and identified areas of agreement and disagreement for feedback to WHO.

Data protection

All confidential data will be kept for 5 years on password-protected computers and/or locked filing cabinets only accessible to members of the research team. During transcription, audio-recordings will be anonymised, with all identifiable information removed prior to using the software analysis tool. All audio-recordings will be destroyed immediately after transcription.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations.

Written informed consent to participate and be audio-recorded will be obtained from all participants. Data management and storage will be subject to the UK Data Protection Act 1998. Ethical approval for the current study was obtained from the Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee (Rec Ref: 16/WM/0479).

Declaration of Helsinki

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, adopted by the 18th World Medical Association (WMA) General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964 and last revised by the 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October (2013).

Output and dissemination

This research has been designed to obtain feedback with recommendations for the ICD-11, and to develop a methodology that can be replicated in other countries that use the ICD system. Additionally, the findings, and learning in terms of the process of co-producing and conducting research with experts by experience, will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications, conferences, media and lay reports.

Service user involvement in MH is a priority. 19 Studies have found that both clinicians and service users have questioned the accuracy, validity and clinical utility of the ICD and other psychiatric diagnostic tools. 3 8 9 11 12 38 Despite this, to date, service user and clinician feedback has not been obtained prior to revision of the ICD manual. In light of this, is not clear whether the content resonates with the experiences of people giving and receiving the diagnoses, could lack clinical utility, or even, cause harm (eg, in terms of the language used).

Limitations

This study is designed to input feedback from service users and clinicians in the forthcoming revision of the ICD. The usefulness of the data and resulting recommendations is dependent on input, that is, reflective of the views of service users and clinicians that the new system will impact. The current study will include two focus groups for each disorder in an attempt to minimise bias 35 and to account for group-think processes that may occur within individual groups. Taking a critical realist epistemological stance is a pragmatic approach to work with discursive data created through the interactional context of a focus group. It is acknowledged that there are multiple competing realities and perspectives that may differ across time and context, and the analysis findings will be limited to the time and context of this study. Transferability of findings is nonetheless maximised by triangulation to ensure the inclusion of multiple stakeholder perspectives, enabled by the advisory and feedback groups of experts by experience that will co-produce the recommendations reported to WHO. Interpretation of the feedback will take into account potential limitations regarding the generalisability of the findings. The current project is exploring only five of the diagnoses that are included in the ICD-11. The ICD is internationally used, and the current project will reflect the experiences and views of service users and clinicians in the UK only. Future research may include both additional diagnostic categories and encapsulate expertise by experience and relevant clinicians in different countries.

The current study will use feedback from experts by experience to co-produce recommendations for the revised diagnostic system proposed for the ICD-11. This feedback aims to improve the accuracy, validity and clinical utility of the manual, and minimise the potential for unintended negative consequences. This qualitative approach has not been previously employed by any countries that use the ICD system. Our vision is that this process will become a routine feature in future revisions of all diagnostic systems.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the library services at Norfolk and Suffolk Foundation Trust for aiding the searching and retrieval of documents. We would like to thank Kevin James (service user governor), Lesley Drew and Sharon Picken (service user involvement leads) for their input during the development of the project. We would also really like to thank Dr Bonnie Teague who generously offered the benefit of her wisdom and proof reading skills.

- Kilbride M ,

- Welford M , et al

- Johnstone L ,

- Bonnington O ,

- Stalker K ,

- Ferguson I ,

- Castillo H ,

- van Rijswijk E ,

- van Hout H ,

- van de Lisdonk E , et al

- Shadbolt N ,

- Starcevic V , et al

- Milton AC ,

- Kelly B , et al

- 16. ↵ Department of Health . Putting People First: Planning together – peer support and self-directed support . London : Department of Health , 2010 .

- 17. ↵ Department of Health . No Health without Mental Health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages . London : Department of Health , 2011 .

- 18. ↵ Department of Health . Closing the Gap: Priorities for essential change in mental health . London : Social Care, Local Government and Care Partnership Directorate , 2014 .

- Simpson EL ,

- Beresford P

- Malone P , et al

- Wilkinson S

- MacQueen KM ,

- Stevens S ,

- Serfaty M , et al

- Carlyle D , et al

- 31. ↵ World Health Organization . The global burden of disease: 2004 update . Switzerland : World Health Organization , 2008 .

- 32. ↵ The British Psychological Society . Diagnosis – policy and guidance . http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/documents/diagnosis-policyguidance.pdf ( accessed Jul 2017 ).

- Schulze B ,

- Angermeyer MC

- Denzin NK ,

Contributors CH is the chief investigator for this project and wrote the protocol. TS is supervising the project and helped to develop all aspects of the project. AG is the expert by experience on the research team, and led on developing the co-production, and the public and patient involvement. CN led the development of the methodology. AP had a specific contribution to the literature review. GMR is the WHO consultant for the project. GMR developed the original idea for the project and has had input into the development of the lay criteria. JR provided input to ethical considerations and the lay criteria. JW led on the development of the lay criteria. All authors supported the development and critical review of the protocol.

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval Coventry and Warwickshire HRA Research Ethics Committee (16/WM/0479).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

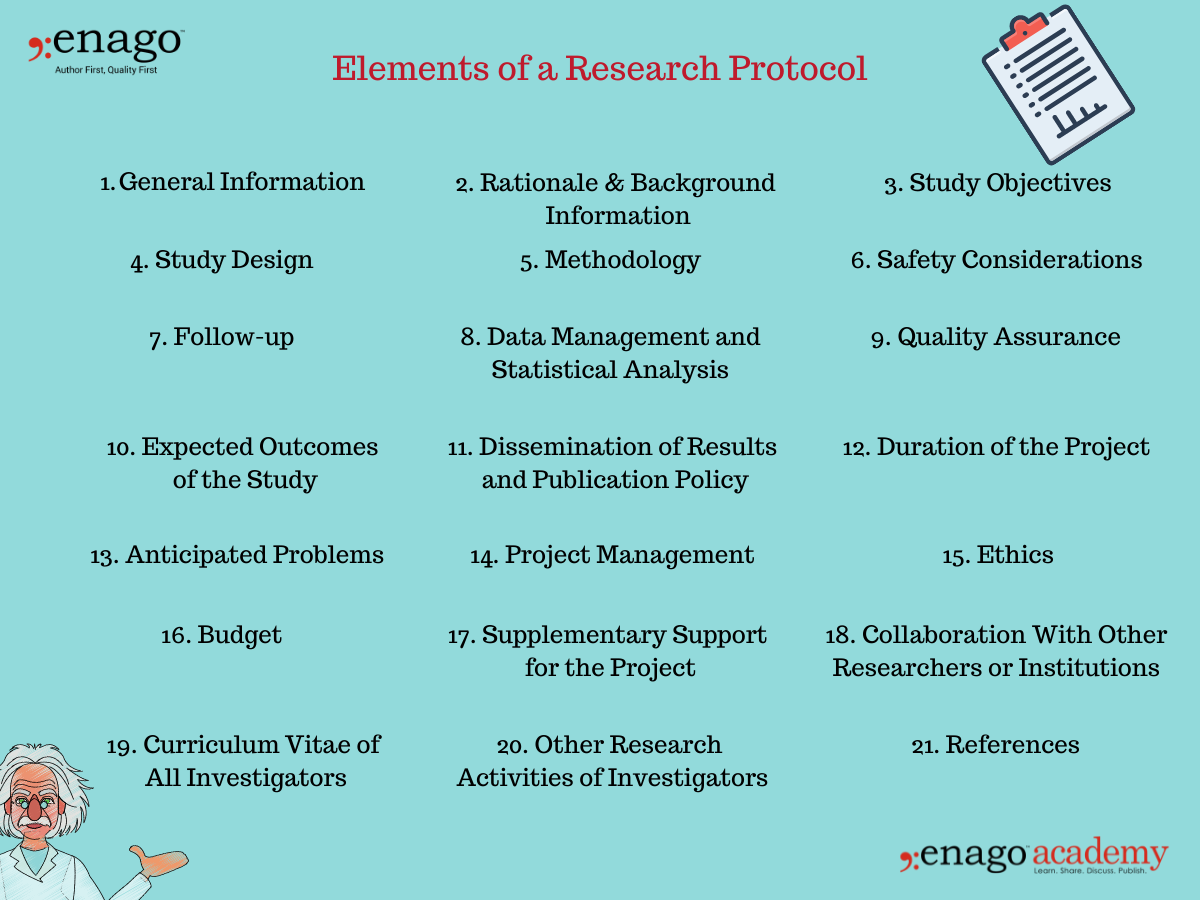

Write an Error-free Research Protocol As Recommended by WHO: 21 Elements You Shouldn’t Miss!

Principal Investigator: Did you draft the research protocol?

Student: Not yet. I have too many questions about it. Why is it important to write a research protocol? Is it similar to research proposal? What should I include in it? How should I structure it? Is there a specific format?

Researchers at an early stage fall short in understanding the purpose and importance of some supplementary documents, let alone how to write them. Let’s better your understanding of writing an acceptance-worthy research protocol.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Protocol?

The research protocol is a document that describes the background, rationale, objective(s), design, methodology, statistical considerations and organization of a clinical trial. It is a document that outlines the clinical research study plan. Furthermore, the research protocol should be designed to provide a satisfactory answer to the research question. The protocol in effect is the cookbook for conducting your study

Why Is Research Protocol Important?

In clinical research, the research protocol is of paramount importance. It forms the basis of a clinical investigation. It ensures the safety of the clinical trial subjects and integrity of the data collected. Serving as a binding document, the research protocol states what you are—and you are not—allowed to study as part of the trial. Furthermore, it is also considered to be the most important document in your application with your Institution’s Review Board (IRB).

It is written with the contributions and inputs from a medical expert, a statistician, pharmacokinetics expert, the clinical research coordinator, and the project manager to ensure all aspects of the study are covered in the final document.

Is Research Protocol Same As Research Proposal?

Often misinterpreted, research protocol is not similar to research proposal. Here are some significant points of difference between a research protocol and a research proposal:

|

|

|

| A is written to persuade the grant committee, university department, instructors, etc. | A research protocol is written to detail a clinical study’s plan to meet specified ethical norms for participating subjects. |

| It is a plan to obtain funding or conduct research. | It is meant to clearly provide an overview of a proposed study to satisfy an organization’s guidelines for protecting the safety of subjects. |

| Research proposals are submitted to funding bodies | Research protocols are submitted to Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) within universities and research centers. |

What Are the Elements/Sections of a Research Protocol?

According to Good Clinical Practice guidelines laid by WHO, a research protocol should include the following:

1. General Information

- Protocol title, protocol identifying number (if any), and date.

- Name and address of the funder.

- Name(s) and contact details of the investigator(s) responsible for conducting the research, the research site(s).

- Responsibilities of each investigator.

- Name(s) and address(es) of the clinical laboratory(ies), other medical and/or technical department(s) and/or institutions involved in the research.

2. Rationale & Background Information

- The rationale and background information provides specific reasons for conducting the research in light of pertinent knowledge about the research topic.

- It is a statement that includes the problem that is the basis of the project, the cause of the research problem, and its possible solutions.

- It should be supported with a brief description of the most relevant literatures published on the research topic.

3. Study Objectives

- The study objectives mentioned in the research proposal states what the investigators hope to accomplish. The research is planned based on this section.

- The research proposal objectives should be simple, clear, specific, and stated prior to conducting the research.

- It could be divided into primary and secondary objectives based on their relativity to the research problem and its solution.

4. Study Design

- The study design justifies the scientific integrity and credibility of the research study.

- The study design should include information on the type of study, the research population or the sampling frame, participation criteria (inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal), and the expected duration of the study.

5. Methodology

- The methodology section is the most critical section of the research protocol.

- It should include detailed information on the interventions to be made, procedures to be used, measurements to be taken, observations to be made, laboratory investigations to be done, etc.

- The methodology should be standardized and clearly defined if multiple sites are engaged in a specified protocol.

6. Safety Considerations

- The safety of participants is a top-tier priority while conducting clinical research .

- Safety aspects of the research should be scrutinized and provided in the research protocol.

7. Follow-up

- The research protocol clearly indicate of what follow up will be provided to the participating subjects.

- It must also include the duration of the follow-up.

8. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

- The research protocol should include information on how the data will be managed, including data handling and coding for computer analysis, monitoring and verification.

- It should clearly outline the statistical methods proposed to be used for the analysis of data.

- For qualitative approaches, specify in detail how the data will be analysed.

9. Quality Assurance

- The research protocol should clearly describe the quality control and quality assurance system.

- These include GCP, follow up by clinical monitors, DSMB, data management, etc.

10. Expected Outcomes of the Study

- This section indicates how the study will contribute to the advancement of current knowledge, how the results will be utilized beyond publications.

- It must mention how the study will affect health care, health systems, or health policies.

11. Dissemination of Results and Publication Policy

- The research protocol should specify not only how the results will be disseminated in the scientific media, but also to the community and/or the participants, the policy makers, etc.

- The publication policy should be clearly discussed as to who will be mentioned as contributors, who will be acknowledged, etc.

12. Duration of the Project

- The protocol should clearly mention the time likely to be taken for completion of each phase of the project.

- Furthermore a detailed timeline for each activity to be undertaken should also be provided.

13. Anticipated Problems

- The investigators may face some difficulties while conducting the clinical research. This section must include all anticipated problems in successfully completing their projects.

- Furthermore, it should also provide possible solutions to deal with these difficulties.

14. Project Management

- This section includes detailed specifications of the role and responsibility of each investigator of the team.

- Everyone involved in the research project must be mentioned here along with the specific duties they have performed in completing the research.

- The research protocol should also describe the ethical considerations relating to the study.

- It should not only be limited to providing ethics approval, but also the issues that are likely to raise ethical concerns.

- Additionally, the ethics section must also describe how the investigator(s) plan to obtain informed consent from the research participants.

- This section should include a detailed commodity-wise and service-wise breakdown of the requested funds.

- It should also include justification of utilization of each listed item.

17. Supplementary Support for the Project

- This section should include information about the received funding and other anticipated funding for the specific project.

18. Collaboration With Other Researchers or Institutions

- Every researcher or institute that has been a part of the research project must be mentioned in detail in this section of the research protocol.

19. Curriculum Vitae of All Investigators

- The CVs of the principal investigator along with all the co-investigators should be attached with the research protocol.

- Ideally, each CV should be limited to one page only, unless a full-length CV is requested.

20. Other Research Activities of Investigators

- A list of all current research projects being conducted by all investigators must be listed here.

21. References

- All relevant references should be mentioned and cited accurately in this section to avoid plagiarism.

How Do You Write a Research Protocol? (Research Protocol Example)

Main Investigator

Number of Involved Centers (for multi-centric studies)

Indicate the reference center

Title of the Study

Protocol ID (acronym)

Keywords (up to 7 specific keywords)

Study Design

Mono-centric/multi-centric

Perspective/retrospective

Controlled/uncontrolled

Open-label/single-blinded or double-blinded

Randomized/non-randomized

n parallel branches/n overlapped branches

Experimental/observational

Endpoints (main primary and secondary endpoints to be listed)

Expected Results

Analyzed Criteria

Main variables/endpoints of the primary analysis

Main variables/endpoints of the secondary analysis

Safety variables

Health Economy (if applicable)

Visits and Examinations

Therapeutic plan and goals

Visits/controls schedule (also with graphics)

Comparison to treatment products (if applicable)

Dose and dosage for the study duration (if applicable)

Formulation and power of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Method of administration of the studied drugs (if applicable)

Informed Consent

Study Population

Short description of the main inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal criteria

Sample Size

Estimated Duration of the Study

Safety Advisory

Classification Needed

Requested Funds

Additional Features (based on study objectives)

Click Here to Download the Research Protocol Example/Template

Be prepared to conduct your clinical research by writing a detailed research protocol. It is as easy as mentioned in this article. Follow the aforementioned path and write an impactful research protocol. All the best!

Clear as template! Please, I need your help to shape me an authentic PROTOCOL RESEARCH on this theme: Using the competency-based approach to foster EFL post beginner learners’ writing ability: the case of Benin context. I’m about to start studies for a master degree. Please help! Thanks for your collaboration. God bless.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

10 Tips to Prevent Research Papers From Being Retracted

Research paper retractions represent a critical event in the scientific community. When a published article…

- Industry News

Google Releases 2024 Scholar Metrics, Evaluates Impact of Scholarly Articles

Google has released its 2024 Scholar Metrics, assessing scholarly articles from 2019 to 2023. This…

![example of a qualitative research protocol What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Neurol Res Pract

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Loraine busetto.

1 Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

2 Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Christoph Gumbinger

Associated data.

Not applicable.

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 – 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 – 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. Fig.2, 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 – 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 – 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 – 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table Table1. 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Take-away-points