- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Qualitative Health Research

| Østfold University College, Norway |

Preview this book

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

Qualitative Health Research provides an international, interdisciplinary forum to enhance health and health care and further the development and understanding of qualitative health research. The journal is an invaluable resource for researchers and academics, administrators and others in the health and social service professions, and graduates, who seek examples of studies in which the authors used qualitative methodologies. Each issue of Qualitative Health Research provides readers with a wealth of information on conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and ethical issues pertaining to qualitative inquiry. A Variety of Perspectives We encourage submissions across all health-related areas and disciplines. Qualitative Health Research understands health in its broadest sense and values contributions from various traditions of qualitative inquiry. As a journal of SAGE Publishing, Qualitative Health Research aspires to disseminate high-quality research and engaged scholarship globally, and we are committed to diversity and inclusion in publishing. We encourage submissions from a diverse range of authors from across all countries and backgrounds. There are no fees payable to submit or publish in Qualitative Health Research .

Original, Timely, and Insightful Scholarship Qualitative Health Research aspires to publish articles addressing significant and contemporary health-related issues. Only manuscripts of sufficient originality and quality that align with the aims and scope of Qualitative Health Research will be reviewed. As part of the submission process authors are required to warrant that they are submitting original work, that they have the rights in the work, that they have obtained, and that can supply all necessary permissions for the reproduction of any copyright works not owned by them, and that they are submitting the work for first publication in the Journal and that it is not being considered for publication elsewhere and has not already been published elsewhere. Please note that Qualitative Health Research does not accept submissions of papers that have been published elsewhere. Sage requires authors to identify preprints upon submission (see https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/preprintsfaq ). This Journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) .

This Journal recommends that authors follow the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals formulated by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE).

Qualitative Health Research is an international, interdisciplinary, refereed journal for the enhancement of health care and to further the development and understanding of qualitative research methods in health care settings. We welcome manuscripts in the following areas: the description and analysis of the illness experience, health and health-seeking behaviors, the experiences of caregivers, the sociocultural organization of health care, health care policy, and related topics. We also seek critical reviews and commentaries addressing conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and ethical issues pertaining to qualitative enquiry.

| Dalhousie University School of Nursing, Canada | |

| Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand | |

| University of Alberta, Canada | |

| Birkbeck University of London, UK | |

| University of Alberta, Canada |

| Université Lumière Lyon 2, France | |

| The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong | |

| University of Tarapaca, Chile | |

| University of Queensland, Australia | |

| University of Colorado, USA | |

| York University, Canada | |

| University of Haifa, Israel | |

| Auckland University of Technology, Aotearoa New Zealand | |

| Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand | |

| Medical University of South Carolina | |

| Birkbeck University of London, UK | |

| University of Queensland, Australia | |

| University of Utah, USA | |

| Christian-Albrechts University Kiel, Germany | |

| Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, India | |

| University of Manitoba, Canada | |

| University of Florida, USA | |

| University of Queensland, Australia | |

| Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong | |

| Hunter College - Silberman School of Social Work, New York, NY |

| University of Utah, USA |

| UC Berkeley, USA | |

| Boston College, USA | |

| University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, Canada | |

| Aalborg University, Denmark | |

| Korea National University of Transportation, South Korea | |

| Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, USA | |

| AUT University Auckland, New Zealand | |

| Freie Universtität Berlin, Germany | |

| Kings College London | |

| University of Calgary, Canada | |

| University of Brighton, UK | |

| Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milan, Italy | |

| University of Illinois at Chicago, USA | |

| Utah Tech University, USA | |

| Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand | |

| Laurentian University, Canada | |

| VinUniversity, Vietnam | |

| University of New South Wales, Australia | |

| University of Alberta, Canada | |

| Portland State University, USA | |

| University of British Columbia, Canada | |

| Professor in the Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada | |

| Ewha Woman's University, South Korea | |

| University of Bologna, Italy | |

| Khon Kaen University, Thailand | |

| University of British Columbia, Canada | |

| University of Alberta, Canada | |

| University of New Brunswick, Canada |

- Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts (ASSIA)

- CAB Abstracts (Index Veterinarius, Veterinary Bulletin)

- CABI: Abstracts on Hygiene and Communicable Diseases

- CABI: CAB Abstracts

- CABI: Global Health

- CABI: Nutrition Abstracts and Reviews Series A

- CABI: Tropical Diseases Bulletin

- Clarivate Analytics: Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences

- Combined Health Information Database (CHID)

- Corporate ResourceNET - Ebsco

- Current Citations Express

- EBSCO: Vocational & Career Collection

- EMBASE/Excerpta Medica

- Family & Society Studies Worldwide (NISC)

- Health Business FullTEXT

- Health Service Abstracts

- Health Source Plus

- MasterFILE - Ebsco

- ProQuest: Applied Social Science Index & Abstracts (ASSIA)

- ProQuest: CSA Sociological Abstracts

- Psychological Abstracts

- Rural Development Abstracts

- SRM Database of Social Research Methodology

- Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science)

- Social Services Abstracts

- Standard Periodical Directory (SPD)

- TOPICsearch - Ebsco

Manuscript submission guidelines:

Qualitative Health Research (QHR) has specific guidelines! While Sage Publishing has general guidelines , all manuscripts submitted to QHR must follow our specific guidelines (found below). Once you have reviewed these guidelines, please visit QHR ’s submission site to upload your manuscript. Please note that manuscripts not conforming to these guidelines will be returned and/or encounter delays in peer review. Remember you can log in to the submission site at any time to check on the progress of your manuscript throughout the peer review process.

1. Deciding whether to submit a manuscript to QHR

1.1 Aims & scope

1.2 Article types

2. Review criteria

2.1 Original research studies

2.2 Pearls, Piths, and Provocations

2.3 Common reasons for rejection

3. Preparing your manuscript

3.1 Title page

3.2 Abstract

3.3 Manuscript

3.4 Tables, Figures, Artwork, and other graphics

3.5 Supplemental material

4. Submitting your manuscript

5. Editorial Policies

5.1 Peer review policy

5.2 Authorship

5.3 Acknowledgments

5.4 Funding

5.5 Declaration of conflicting interests

5.6 Research ethics and participant consent

6. Publishing Policies

6.1 Publication ethics

6.2 Contribtor's publishing agreement

6.3 Open access and author archiving

1. Deciding whether to submit a manuscript to QHR

QHR provides an international, interdisciplinary forum to enhance health and health care and further the development and understanding of qualitative health research. The journal is an invaluable resource for researchers and academics, administrators and others in the health and social service professions, and graduates, who seek examples of studies in which the authors used qualitative methodologies. Each issue of QHR provides readers with a wealth of information on conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and ethical issues pertaining to qualitative inquiry.

Rather than send query letters to the Editor regarding article fit, QHR asks authors to make their own decision regarding the suitability of their manuscript for QHR by asking: Does your proposed submission make a meaningful and strong contribution to qualitative health research literature? Is it useful to readers and/or practitioners?

The following manuscript types are considered for publication.

- Original Research Studies : These are fully developed qualitative research studies. This may include mixed method studies in which the major focus/portion of the study is qualitative research. Please read Maintaining the Integrity of Qualitatively Driven Mixed Methods: Avoiding the “ This Work is Part of a Larger Study” Syndrome .

- Pearls, Piths, and Provocations : These manuscripts should foster discussion and debate about significant issues, enhance communication of methodological advances, promote and discuss issues related to the teaching of qualitative approaches in health contexts, and/or encourage the discussion of new and/or provocative ideas. They should also make clear what the manuscript adds to the existing body of knowledge in the area.

- Editorials : These are generally invited articles written by editors/editorial board members associated with QHR.

Please note, QHR does NOT publish pilot studies. We do not normally publish literature reviews unless they focus on qualitative research studies elaborating methodological issues and developments. Review articles should be submitted to the Pearls, Piths, and Provocations section. They are reviewed according to criteria in 2.2.

Back to top

2. Review criteria

2.1 Original research

Reviewers are asked to consider the following areas and questions when making recommendations about research manuscripts:

- Importance of submission : Does the manuscript make a significant contribution to qualitative health research literature? Is it original? Relevant? In depth? Insightful? Is it useful to the reader and/or practitioner?

- Methodological considerations : Is the overall study design clearly explained including why this design was an appropriate one? Are the methodology/methods/approaches used in keeping with that design? Are they appropriate given the research question and/or aims? Are they logically articulated? Clarity in design and presentation? Data adequacy and appropriateness? Evidence of rigor?

- Ethical Concerns : Are relevant ethical concerns discussed and acknowledged? Is enough detail given to enable the reader to understand how ethical issues were navigated? Has formal IRB approval (when needed) and consent from participants been obtained?

- Data analysis, findings, discussion : Does the analysis of data reflect depth and coherence? In-depth descriptive but also interpretive dimensions? Creative and insightful analysis? Are results linked to existing literature and theory, as appropriate? Is the contribution of the research clear including its relevance to health disciplines and their practice?

- Manuscript style and format : Is the manuscript organized in a clear and concise manner? Has sufficient attention been paid to word choice, spelling, grammar, and so forth? Did the author adhere to APA guidelines? Do diagrams/illustrations comply with guidelines? Is the overall manuscript aligned with QHR guidelines in relation to formatting?

- Scope: Does the article fit with QHR ’s publication mandate? Has the author cited the major work in the area, including those published in QHR ?

The purpose of papers in this section is to raise and discuss issues pertinent to the development and advancement of qualitative research in health-related arenas. As the name Pearls, Piths, and Provocations suggests, we are looking for manuscripts that make a significant contribution to areas of dialogue, development, experience sharing and debate relevant to the scope of QHR in this section of the journal. Reviewers are asked to consider the following questions when making recommendations about articles in the Pearls, Piths, and Provocations section.

- Significance : Does the paper highlight issues that have the potential to advance, develop, and/or challenge thinking in qualitative health related research?

- Clarity : Are the arguments clearly presented and well supported?

- Rigor : Is there the explicit use of/interaction with methodology and/or theory and/or empirical studies (depending on the focus of the paper) that grounds the work and is coherently carried throughout the arguments and/or analysis in the manuscript? Put another way, is there evidence of a rigorously constructed argument?

- Engagement : Does the paper have the potential to engage the reader to ‘think differently’ by raising questions, suggesting innovative directions for qualitative health research, and/or stimulating critical reflection? Are the implications of the paper for the practice of either qualitative research and/or health clear?

- Quality of the writing : Is the main argument of the paper clearly articulated and presented with few grammatical or typographical issues? Are terms and concepts key to the scholarship communicated clearly and in sufficient detail?

QHR most commonly turns away manuscripts that fall outside the journal’s scope, do not make a novel contribution to the literature, lack substantive and/or interpretative depth, require extensive revisions, and/or do not adequately address ethical issues that are fundamental to qualitative inquiry. Submissions of the supplementary component of mixed methods studies often are rejected as the findings are difficult to interpret without the findings of the primary study. For additional information on this policy, please read Maintaining the Integrity of Qualitatively Driven Mixed Methods: Avoiding the “ This Work is Part of a Larger Study” Syndrome .

3. Preparing your manuscript for submission

We strongly encourage all authors to review previously published articles in QHR for style prior to submission.

QHR journal practices include double anonymization. All identifying information MUST be removed completely from the Abstract, Manuscript, Acknowledgements, Tables, and Figure files prior to submission. ONLY the Title Page and Cover Letter may contain identifying information. See Sage’s general submission guidelines for additional guidance on making an anonymous submission.

Preferred formats for the text and tables of your manuscript are Word DOC or PDF. The text must be double-spaced throughout with standard 1-inch margins (APA formatting). Text should be standard font (i.e., Times New Roman) 12-point.

3.1 Title page

- The title page should be uploaded as a separate document containing the following information: Author names; Affiliations; Author contact information; Contribution list; Acknowledgements; Ethical statement; Funding Statement; Conflict of Interest Statements; and, Grant Number. Please know that the Title Page is NOT included in the materials sent out for Peer Review.

- Ethical statement: An ethical statement must include the following: the full name of the ethical board that approved your study; the approval number given by the ethical board; and, confirmation that all your participants gave informed consent. Authors are also required to state in the methods section whether participants provided informed consent, whether the consent was written or verbal, and how it was obtained and by whom. For example: “Our study was approved by The Mercy Health Research Ethics Committee (approval no. XYZ123). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.” If your study did not need ethical approval (often manuscripts in the Pearls, Piths, and Provocations may not), we still need a statement that states that your study did not need approval and an explanation as to why. For example: “Ethical Statement: Our study did not require an ethical board approval because it did not directly involve humans or animals.”

3.2 Abstract and Keywords

- The Abstract should be unstructured, written in narrative form. Maximum of 250 words. This should be on its own page, appearing as the first page of the Main Manuscript file.

- The keywords should be included beneath the abstract on the Main Manuscript file.

- Length: 8,000 words or less excluding the abstract, list of references, and acknowledgements. This applies to both Original Research and Pearls, Piths, and Provocations. Please note that text from Tables and Figures is included in the word count limits. On-line supplementary materials are not included in the word limit.

- Structure: While many authors will choose to use headings of Background, Methods, Results, and Discussion to organize their manuscript, it is up to authors to choose the most appropriate terms and structure for their submission. It is the expectation that manuscripts contain detailed reflections on methodological considerations.

- Ethics: In studies where data collection or other methods present ethical challenges, the authors should explicate how such issues were navigated including how consent was gained and by whom. An anonymized version of the ethical statement should be included in the manuscript (in addition to appearing on the title page).

- Participant identification: Generally, demographics should be described in narrative form or otherwise reported as a group. Quotations may be linked to particular participants and/or demographic features provided measures are taken to ensure anonymity of participants (e.g., use of pseudonyms).

- Use of checklists: Authors should not include qualitative research checklists, such as COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research). Generally, authors should use a narrative approach to describe the processes used to enhance the rigor of their study. For additional information on this policy, please read Why the Qualitative Health Research (QHR) Review Process Does Not Use Checklists

- References: APA format. While there is no limit to the number of references, authors are recommended to use pertinent references only, including literature previously published in QHR . References should be on a separate page. QHR adheres to the APA 7 reference style. View the APA guidelines to ensure your manuscript conforms to this reference style. Please ensure you check carefully that both your in-text references and list of references are in the correct format.

- Authors are required to disclose the use of generative Artificial Intelligence (such as ChatGPT) and other technologies (such as NVivo, ATLAS. Ti, Quirkos, etc.), whether used to conceive ideas, develop study design, generate data, assist in analysis, present study findings, or other activities formative of qualitative research. We suggest authors provide both a description of the technology, when it was accessed, and how it was used (see https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/chatgpt-and-generative-ai ).

- Manuscripts that receive favorable reviews will not be accepted until any formatting and copy-editing required has been done.

- Tables, Figures, Artwork, and other graphics should be submitted as separate files rather than incorporated into the main manuscript file. Within the manuscript, indicate where these items should appear (i.e. INSERT TABLE 1 HERE).

- TIFF, JPED, or common picture formats accepted. The preferred format for graphs and line art is EPS.

- Resolution: Rasterized based files (i.e. with .tiff or .jpeg extension) require a resolution of at least 300 dpi (dots per inch). Line art should be supplied with a minimum resolution of 800 dpi.

- Dimension: Check that the artworks supplied match or exceed the dimensions of the journal. Images cannot be scaled up after origination.

- Figures supplied in color will appear in color online regardless of whether or not these illustrations are reproduced in color in the printed version. For specifically requested color reproduction in print, you will receive information regarding the costs from Sage after receipt of your accepted article.

- Core elements of the manuscript should not be included as supplementary material.

- QHR is able to host additional materials online (e.g., datasets, podcasts, videos, images etc.) alongside the full-text of the article. For more information please refer to Sage’s general guidelines on submitting supplemental files .

4. Submitting your manuscript

QHR is hosted on Sage Track, a web based online submission and peer review system powered by ScholarOne™ Manuscripts. Visit https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/QHR to login and submit your article online.

IMPORTANT: Please check whether you already have an account in the system before trying to create a new one. If you have reviewed or authored for the Journal in the past year it is likely that you will have had an account created. For further guidance on submitting your manuscript online please visit ScholarOne Online Help .

5. Editorial policies

QHR adheres to a rigorous double-anonymized reviewing policy in which the identities of both the reviewer and author are always concealed from both parties.

Sage does not permit the use of author-suggested (recommended) reviewers at any stage of the submission process, be that through the web-based submission system or other communication. Reviewers should be experts in their fields and should be able to provide an objective assessment of the manuscript. Our policy is that reviewers should not be assigned to a manuscript if:

• The reviewer is based at the same institution as any of the co-authors

• The reviewer is based at the funding body of the manuscript

• The author has recommended the reviewer

• The reviewer has provided a personal (e.g. Gmail/Yahoo/Hotmail) email account and an institutional email account cannot be found after performing a basic Google search (name, department and institution).

Qualitative Health Research is committed to delivering high quality, fast peer-review for your manuscript, and as such has partnered with Web of Science. Web of Science is a third-party service that seeks to track, verify and give credit for peer review. Reviewers for Qualitative Health Research can opt in to Web of Science in order to claim their reviews or have them automatically verified and added to their reviewer profile. Reviewers claiming credit for their review will be associated with the relevant journal, but the article name, reviewer’s decision, and the content of their review is not published on the site. For more information visit the Web of Science website.

The Editor or members of the Editorial Team or Board may occasionally submit their own manuscripts for possible publication in the Journal. In these cases, the peer review process will be managed by alternative members of the Editorial Team or Board and the submitting Editor Team/Board member will have no involvement in the decision-making process.

Manuscripts should only be submitted for consideration once consent is given by all contributing authors. Those submitting manuscripts should carefully check that all those whose work contributed to the manuscript are acknowledged as contributing authors. The list of authors should include all those who can legitimately claim authorship. This is all those who meet all of the following criteria:

(i) Made a substantial contribution to the design of the work or acquisition, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of data, (ii) Drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content, (iii) Approved the version to be published, (iv) Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Acquisition of funding, collection of data, or general supervision of the research group alone does not constitute authorship, although all contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship should be listed in the Acknowledgments section. Please refer to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship guidelines for more information on authorship.

Authors are required to disclose the use of generative Artificial Intelligence (such as ChatGPT) and other technologies (such as NVivo, ATLAS. Ti, Quirkos, etc.), whether used to conceive ideas, develop study design, generate data, assist in analysis, present study findings, or other activities formative of qualitative research. We suggest authors provide both a description of the technology, when it was accessed, and how it was used. This needs to be clearly identified within the text and acknowledged within your Acknowledgements section. Please note that AI bots such as ChatGPT should not be listed as an author. For more details on this policy, please visit ChatGPT and Generative AI .

5.3 Acknowledgements

All contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship should be listed in an Acknowledgements section. Examples of those who might be acknowledged include a person who provided purely technical help, or a department chair who provided only general support.

Please supply any personal acknowledgements separately to the main text to facilitate anonymous peer review.

Per ICMJE recommendations , it is best practice to obtain consent from non-author contributors who you are acknowledging in your manuscript.

1.3.1 Writing assistance

Individuals who provided writing assistance, e.g., from a specialist communications company, do not qualify as authors and so should be included in the Acknowledgements section. Authors must disclose any writing assistance – including the individual’s name, company and level of input – and identify the entity that paid for this assistance. It is not necessary to disclose use of language polishing services.

Qualitative Health Research requires all authors to acknowledge their funding in a consistent fashion under a separate heading. Please visit the Funding Acknowledgements page on the Sage Journal Author Gateway to confirm the format of the acknowledgment text in the event of funding, or state that: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

It is the policy of Qualitative Health Research to require a declaration of conflicting interests from all authors enabling a statement to be carried within the paginated pages of all published articles.

Please ensure that a ‘Declaration of Conflicting Interests’ statement is included at the end of your manuscript, after any acknowledgements and prior to the references. If no conflict exists, please state that ‘The Author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest’. For guidance on conflict of interest statements, please see the ICMJE recommendations here .

Research involving participants must be conducted according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki

Submitted manuscripts should conform to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals :

All manuscripts must state that the relevant Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board provided (or waived) approval. Please ensure that you blind the name and institution of the review committee until such time as your article has been accepted. The Editor will request authors to replace the name and add the approval number once the article review has been completed. Please note that in itself, simply stating that Ethics Committee or Institutional Review was obtained is not sufficient. Authors are also required to state in the methods section whether participants provided informed consent, whether the consent was written or verbal, and how it was obtained and by whom.

Please do not submit the participant’s informed consent documents with your article, as this in itself breaches the participant’s confidentiality. The Journal requests that you confirm to us, in writing, that you have obtained informed consent recognizing the documentation of consent itself should be held by the authors/investigators themselves (for example, in a participant’s hospital record or an author’s institution’s archives).

Please also refer to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Protection of Research Participants .

6. Publishing Policies

Sage is committed to upholding the integrity of the academic record. We encourage authors to refer to the Committee on Publication Ethics’ International Standards for Authors and view the Publication Ethics page on the Sage Author Gateway .

6.1.1 Plagiarism

Qualitative Health Research and Sage take issues of copyright infringement, plagiarism or other breaches of best practice in publication very seriously. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) defines plagiarism as: “When somebody presents the work of others (data, words or theories) as if they were his/her own and without proper acknowledgment.” We seek to protect the rights of our authors and we always investigate claims of plagiarism or misuse of published articles. Equally, we seek to protect the reputation of the journal against malpractice. Submitted articles may be checked with duplication-checking software. Where an article, for example, is found to have plagiarised other work or included third-party copyright material without permission or with insufficient acknowledgement, or where the authorship of the article is contested, we reserve the right to take action including, but not limited to: publishing an erratum or corrigendum (correction); retracting the article; taking up the matter with the head of department or dean of the author's institution and/or relevant academic bodies or societies; or taking appropriate legal action.

6.1.2 Prior publication

If material has been previously published it is not generally acceptable for publication in a Sage journal. However, there are certain circumstances where previously published material can be considered for publication. Please refer to the guidance on the Sage Author Gateway or if in doubt, contact the Editor at the address given below.

6.2 Contributor's publishing agreement

Before publication, Sage requires the author as the rights holder to sign a Journal Contributor’s Publishing Agreement. Sage’s Journal Contributor’s Publishing Agreement is an exclusive licence agreement which means that the author retains copyright of the work but grants Sage the sole and exclusive right and licence to publish for the full legal term of copyright. Exceptions may exist where an assignment of copyright is required or preferred by a proprietor other than Sage. In this case copyright in the work will be assigned from the author to the society. For more information please visit the Sage Author Gateway .

Qualitative Health Research offers optional open access publishing via the Sage Choice programme and Open Access agreements, where authors can publish open access either discounted or free of charge depending on the agreement with Sage. Find out if your institution is participating by visiting Open Access Agreements at Sage . For more information on Open Access publishing options at Sage please visit Sage Open Access . For information on funding body compliance, and depositing your article in repositories, please visit Sage’s Author Archiving and Re-Use Guidelines and Publishing Policies .

- Read Online

- Sample Issues

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Permissions

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Individual Subscription, E-access

Individual Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Backfile Purchase, E-access (Content through 1998)

Institutional Subscription, E-access

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, E-access Plus Backfile (All Online Content)

Institutional Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, Combined Plus Backfile (Current Volume Print & All Online Content)

Individual, Single Print Issue

Institutional, Single Print Issue

To order single issues of this journal, please contact SAGE Customer Services at 1-800-818-7243 / 1-805-583-9774 with details of the volume and issue you would like to purchase.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Qualitative research in healthcare: an introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis

Affiliation.

- 1 AL Chapman, Department of Infectious Diseases, Monklands Hospital, Airdrie ML6 0JS, UK. Email [email protected].

- PMID: 26517098

- DOI: 10.4997/JRCPE.2015.305

In today's NHS, qualitative research is increasingly important as a method of assessing and improving quality of care. Grounded theory has developed as an analytical approach to qualitative data over the last 40 years. It is primarily an inductive process whereby theoretical insights are generated from data, in contrast to deductive research where theoretical hypotheses are tested via data collection. Grounded theory has been one of the main contributors to the acceptance of qualitative methods in a wide range of applied social sciences. The influence of grounded theory as an approach is, in part, based on its provision of an explicit framework for analysis and theory generation. Furthermore the stress upon grounding research in the reality of participants has also given it credence in healthcare research. As with all analytical approaches, grounded theory has drawbacks and limitations. It is important to have an understanding of these in order to assess the applicability of this approach to healthcare research. In this review we outline the principles of grounded theory, and focus on thematic analysis as the analytical approach used most frequently in grounded theory studies, with the aim of providing clinicians with the skills to critically review studies using this methodology.

Keywords: grounded theory; healthcare; inductive analysis; qualitative research; quality improvement; thematic analysis.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Grounded theory as a method for research in speech and language therapy. Skeat J, Perry A. Skeat J, et al. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008 Mar-Apr;43(2):95-109. doi: 10.1080/13682820701437245. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008. PMID: 17852520 Review.

- Participants' views of telephone interviews within a grounded theory study. Ward K, Gott M, Hoare K. Ward K, et al. J Adv Nurs. 2015 Dec;71(12):2775-85. doi: 10.1111/jan.12748. Epub 2015 Aug 10. J Adv Nurs. 2015. PMID: 26256835

- Applications of Grounded Theory Methodology to Investigate Hearing Loss: A Methodological Qualitative Systematic Review With Developed Guidelines. Ali Y, Wright N, Charnock D, Henshaw H, Morris H, Hoare DJ. Ali Y, et al. Ear Hear. 2024 May-Jun 01;45(3):550-562. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001459. Epub 2024 Apr 14. Ear Hear. 2024. PMID: 38608196 Free PMC article.

- The grounded theory method and maternal-infant research and practice. Marcellus L. Marcellus L. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005 May-Jun;34(3):349-57. doi: 10.1177/0884217505276053. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005. PMID: 15890834 Review.

- Is it really theoretical? A review of sampling in grounded theory studies in nursing journals. McCrae N, Purssell E. McCrae N, et al. J Adv Nurs. 2016 Oct;72(10):2284-93. doi: 10.1111/jan.12986. Epub 2016 Apr 26. J Adv Nurs. 2016. PMID: 27113800 Review.

- Nurse rostering: understanding the current shift work scheduling processes, benefits, limitations, and potential fatigue risks. Booker LA, Mills J, Bish M, Spong J, Deacon-Crouch M, Skinner TC. Booker LA, et al. BMC Nurs. 2024 Apr 29;23(1):295. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-01949-2. BMC Nurs. 2024. PMID: 38685019 Free PMC article.

- Role of family medicine physicians in providing nutrition support to older patients admitted to orthopedics departments: a grounded theory approach. Ohta R, Nitta T, Shimizu A, Sano C. Ohta R, et al. BMC Prim Care. 2024 Apr 19;25(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s12875-024-02379-4. BMC Prim Care. 2024. PMID: 38641569 Free PMC article.

- Implementation of a critical care outreach team in a children's hospital. Mehta S, Galligan MM, Lopez KT, Chambers C, Kabat D, Papili K, Stinson H, Sutton RM. Mehta S, et al. Resusc Plus. 2024 Apr 11;18:100626. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2024.100626. eCollection 2024 Jun. Resusc Plus. 2024. PMID: 38623378 Free PMC article.

- Early Impressions and Adoption of the AtriAmp for Managing Arrhythmias Following Congenital Heart Surgery. Leopold SM, Brown DH, Zhang X, Nguyen XT, Al-Subu AM, Olson KR. Leopold SM, et al. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2024 Mar 21:rs.3.rs-4125331. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4125331/v1. Res Sq. 2024. Update in: Pediatr Cardiol. 2024 Jul 6. doi: 10.1007/s00246-024-03573-y. PMID: 38562710 Free PMC article. Updated. Preprint.

- Developing an innovative national ACP-OSCE program in Taiwan: a mixed method study. Wu YL, Hsieh TY, Hwang SF, Lin YY, Chu WM. Wu YL, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Mar 23;24(1):333. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05294-5. BMC Med Educ. 2024. PMID: 38521917 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Enlighten: Publications, University of Glasgow

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

762k Accesses

337 Citations

89 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

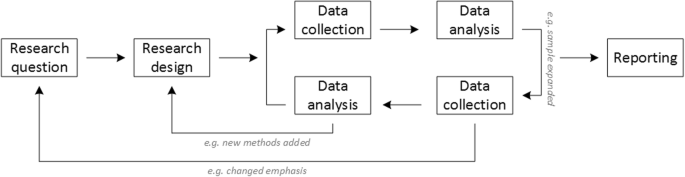

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

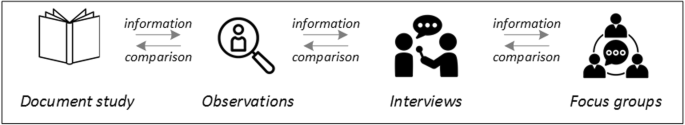

Data collection

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

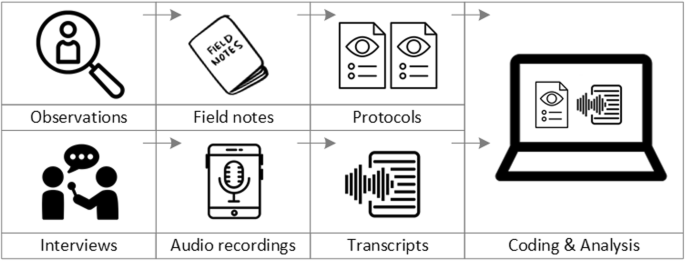

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

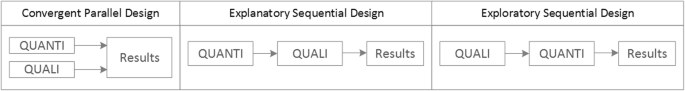

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.