A Short Guide to Building Your Team’s Critical Thinking Skills

by Matt Plummer

Summary .

Most employers lack an effective way to objectively assess critical thinking skills and most managers don’t know how to provide specific instruction to team members in need of becoming better thinkers. Instead, most managers employ a sink-or-swim approach, ultimately creating work-arounds to keep those who can’t figure out how to “swim” from making important decisions. But it doesn’t have to be this way. To demystify what critical thinking is and how it is developed, the author’s team turned to three research-backed models: The Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment, Pearson’s RED Critical Thinking Model, and Bloom’s Taxonomy. Using these models, they developed the Critical Thinking Roadmap, a framework that breaks critical thinking down into four measurable phases: the ability to execute, synthesize, recommend, and generate.

With critical thinking ranking among the most in-demand skills for job candidates , you would think that educational institutions would prepare candidates well to be exceptional thinkers, and employers would be adept at developing such skills in existing employees. Unfortunately, both are largely untrue.

Partner Center

- HR Most Influential

- HR Excellence Awards

- Advertising

Search menu

Helen Lee Bouygues

Reboot Foundation

View articles

Improving the workplace through critical thinking

A lot of the problems in business — and in human resources — can be traced back to a single root: bad thinking. Over the course of my career as a consultant, I’ve seen business leaders make abysmal decisions based on faulty reasoning, and I’ve seen HR managers fail to recognise their own innate biases when addressing employee complaints and hiring decisions.

Let me give you an example. I was once asked to help turn around a large, but faltering, lingerie company in Europe. It didn’t take too long for me to see what the problem was: the company’s strategy assumed that all their customers everywhere pretty much wanted the same products.

Company leaders hadn’t done their research and didn’t really understand how their customers’ preferences varied from country to country.

In the UK, for example, lacy bras in bright colours sold the best; Italians seemed to prefer beige bras without lace; and Americans opted for sports bras in much, much larger numbers.

Transformations and turnarounds:

What to do when leadership fails

How HR can prioritise procedure using automation and digital processes

How to transform dysfunctional teams

Without realising it, they were making business decisions on faulty assumptions and bad information. However, a new strategy based on market-dependent research quickly helped turn things around.

Using feedback to get outside of your own head

One huge advantage consultants have over internal employees is simply that they are outsiders. Consultants obviously won’t know the ins and outs of the business as well as internal managers, but because of that, they also haven’t developed the biases and assumptions that can constrain employee thinking. In short, employees are sometimes too close to the problem.

Now, there are a lot of exercises and routines you can employ to make sure you don’t have blinders on when you’re confronting new problems or challenges.

Perhaps the easiest way to do this is through feedback. Of course, feedback can be tricky. No one likes to be evaluated harshly, and without the proper mechanisms in place the value of feedback may be lost amid negative interpersonal dynamics.

One of the best things an organisation can do is to implement clear and explicit practices and guidelines for feedback between managers and employees.

Feedback should be cooperative rather than antagonistic. It should give both parties the opportunity to reflect on, explain, and refine their reasoning. And it should be explicit, preferably using both written and oral communication to find flaws in reasoning and tease out new solutions.

Making conflict productive

Conflict is inevitable in a workplace. It’s how conflict is managed that can determine whether an organisation thrives. The key to good decision-making in group settings is productive, rather than destructive, conflict.

The best decisions emerge from a process in which ideas have to do battle with one another and prove their worth in group discussions. Without some conflict, organisations fall prey to group-think , where everyone goes along with the consensus.

Again, process is crucial here. The best organisations have clear guidelines and structures in place to ensure decision-making proceeds productively.

Decision-making practices should also include mechanisms for avoiding groupthink, by, for example, soliciting opinions in writing before a discussion and by composing groups with a diverse range of backgrounds and opinions.

Finally, leaders must truly value dissenting opinions. Special consideration should be given to ideas that go against the grain. Even if they lose out in the end, dissenting opinions make the final decision stronger.

Dissenters will also be more likely to buy into a decision that goes against their views if they feel their voice has been genuinely heard.

Thinking through individual goals critically and creatively

A key component of workplace happiness is employees’ sense that they are working toward something , both in terms of overall organisational goals and in terms of personal and professional growth.

Regular reflection on individual goals is vital to sustaining a healthy workplace culture. It also encourages more thoughtful work and allows employees to see day-to-day tasks in a broader context, helping them avoid burnout and monotony .

HR professionals can implement regular systems that allow employees to intentionally formulate these types of goals and understand how their work can be integrated more fully into achieving those goals.

Organisations can also grant employees time to pursue passion projects, like Google has, to give workers the freedom to develop ideas and products beneficial to both themselves and the company.

Creative and critical thinking is integral to organisational success, but it is too often assumed that employees and organisations either have it or they don’t.

The truth is that good thinking can be fostered with intentional, structured systems in place for feedback, argument, and reflection.

Helen Lee Bouygues is founder of the Reboot Foundation

Further reading

LinkedIn’s dyslexic thinking skill: de-stigmatisation or discrimination?

Six top tips for navigating challenging conversations in the workplace

What’s in a name: supporting workplace inclusivity through #MyNameIs

The power of design thinking

Why microclimates have the power to change workplace culture

Why we need to ditch the job description

Managing the upside-down: lessons from Stranger Things

The 'power partnership': why CPOs and CMOs have a common cause

HR Daily Advisor

Practical HR Tips, News & Advice. Updated Daily.

Learning & Development, Talent

Why critical thinking is so important.

Updated: Oct 16, 2020

What Is Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.

Value of Critical Thinking

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

NOURISH YOUR MIND. IGNITE YOUR SOUL. Multiply Your Success with Deep Insights from John Mattone

THE WORLD’S #1 EXECUTIVE COACHING AND BUSINESS COACHING BLOG SINCE 2017.

How Critical Thinking Helps Leaders Work Through Problems

June 19, 2024 | Category: Blog , Critical Thinking

Most leaders associate critical thinking skills with achieving high-level performance and superior problem-solving abilities.

Modern business is becoming more complex every year, with potential consequences for managers and leaders who don’t keep up with the fast-paced changes. Leaders and their actions are closely watched by the public, and leadership accountability is an integral part of a thriving corporate culture .

This is why leaders are expected to show skills that enable fast and efficient problem-solving. Critical thinking enables leaders to draw the right conclusions and make the right strategic decisions to create a growing organization. It is one of the most important and expected skills in a modern leader’s toolbox.

Are Good Critical Thinking Skills Vital for Success?

Yes, critical thinking is a vital leadership skill. It enables leaders to rise above the noise, assumptions, and biases that can sabotage decision-making.

Critical thinking is an analytic approach to problem-solving and decision-making. By developing their critical thinking skills, leaders can improve their decision-making and enhance their organization’s position.

Leadership coaching can help leaders develop critical thinking , training their minds to think instead of merely learning facts. This helps leaders anticipate the many potential outcomes and consequences of their decisions and develop innovative solutions with their company.

Critical thinkers understand logical relationships and connect them with the “big picture” corporate vision and mission .

Critical Thinking in Leadership

Critical thinking optimizes decision-making. But in the context of intelligent leadership , it does more. Critical thinking makes strategic decisions with desirable outcomes more likely.

Like intelligent leadership itself, it is reasoned, purposeful, and goal-focused. It allows leaders to formulate informed and relevant ideas and inferences, solve problems, calculate probabilities, and make better decisions.

In my book, Intelligent Leadership , I have defined critical thinking as an essential outer-core leadership competency. Since the quality of leadership depends on the leader’s quality of thoughts, critical thinking skills define one’s effectiveness as a leader.

What Does The Data Say? Critical Thinking for Leaders and Managers

From interviews and surveys of 150 human resources executives, experts estimated that only 1 to 28 percent of current leaders in their organizations demonstrated “excellent” critical thinking skills ( Bonnie Hagemann and John Mattone for Pearson, 2011 ).

Critical thinking helps you differentiate facts from assumptions.

Much of the instinctive thinking as a leader, if not carefully examined, tends to be biased, distorted, partial, uninformed, or even prejudiced.

Effective critical thinking requires evaluating all possible aspects of a problem, including emotional, cognitive, intellectual, and psychological factors.

Critical thinking is the opposite of instinctive thinking. Emotional intelligence , which complements critical thinking on the outer-core strategic competencies wheel, plays a critical role in the process by helping leaders manage their emotions and understand others’ emotions, thereby enhancing their ability to think critically and make effective decisions.

Critical Thinking vs Strategic Thinking

Critical thinking is the core component of strategic thinking , a less abstract measure of one’s ability to lead. In addition to strategic thinking, critical thinking allows leaders to:

- Embrace change

- Inspire others

- Create a vision and rally the “troops’ around it

- Understand how the different parts of the organization work together as a whole

Shallow thinking by leaders is costly. It hurts the organization, the employees, and the clients. Critical thinking enables leaders to apply their knowledge to the everyday challenges of their work. Thus, instead of walking-talking encyclopedias, they become valuable decision-making assets for their organizations and employees.

Effective leaders with good critical thinking skills can model this behavior for their peers and reports, further improving the company’s talent and leadership pool.

Are leaders born with critical thinking skills?

The answer is no. Critical thinking skills don’t come naturally to leaders. Even the top five percent of leaders, often considered “natural born leaders ” have to work and develop the skills of critical thinking to be able to use it effectively in the business world.

The learning process requires leaders to look “under the hood.” If we don’t understand what drives us and how we make decisions, we can overlook fundamental issues that could negatively impact our organization.

How can we cultivate critical thinkers?

As a leadership development coaching expert, I firmly believe that it is possible to learn and practice all inner and outer-core leadership competencies. That includes critical thinking.

In my executive coaching books and blog posts , I have deconstructed critical thinking into three components.

The Ability to Recognize Assumptions

An assumption is a conclusion one reaches through the filter of one’s biases, desires, and views. Facts are observable. They exist without the need for validation. Basing decisions on assumptions instead of facts is risky and ill-advised.

The Ability to Evaluate Arguments

Leaders capable of critical thinking look to solve problems by reducing them to basic principles, considering alternatives, and challenging or testing assumptions.

The Ability to Draw Conclusions

Having gathered plenty of quality data and putting it through the filter of their critical thinking skills, intelligent leaders can draw better, more relevant conclusions that lead to better decisions.

Executive coaching can improve critical thinking by improving the sub-skills that contribute to it.

Critical thinking is an essential competency of John Mattone’s Intelligent Leadership framework.

Critical Thinking Process and Approach to Problem-Solving

As described in my book, Intelligent Leadership emphasizes a strategic and reflective approach to problem-solving. This process involves several key steps:

- Deep Reflection : Leaders are encouraged to engage in deep reflection to understand the underlying issues and dynamics of the problems they face.

- Strategic Analysis : Critical thinking requires analyzing the problem from various angles to identify potential solutions and outcomes. This involves evaluating the risks and benefits of different approaches and practical strategies.

- Consultation and Collaboration : Leaders are advised to consult with others, gathering diverse perspectives to enrich their understanding and solution strategies.

- Decisive Action : Once a thorough analysis is complete, effective leaders make informed decisions and act decisively, implementing solutions with precision and adaptability.

- Evaluation and Adjustment : After taking action, the process includes evaluating the outcomes and making necessary adjustments. This continuous loop of reflection, analysis, action, and evaluation forms the core of critical thinking in leadership.

This methodological approach helps critical thinkers not only solve problems more effectively but also develop a deeper understanding and stronger foundation in leadership capabilities by enhancing their analytical and decision-making skills.

How Leadership Coaching Can Help Develop Critical Thinking Skills

Leadership coaching, at least the way I understand it, views critical thinking as one of the fundamental levers through which it can effect meaningful, sustainable, positive change.

Business coaching and executive coaching professionals work with leaders, helping them assess their existing critical thinking skills, provide practical solutions to improve their skills and measure their progress.

Executive leadership coaching can help develop and train critical thinking skills in many ways:

- A leadership coach can give you an objective assessment of your current critical thinking skills.

- Executive coaches know how to ask the right questions to steer their coachees onto the path of improvement.

- Leadership coaching considers self-awareness and emotional intelligence the cornerstones of intelligent leadership. Self-aware and emotionally intelligent leaders understand the value of different perspectives.

- Business coaching encourages leaders to understand the strategic drivers of success for their organization in practical, financial terms.

- Coaches can provide valuable input, critique, and opinions, introducing alternative views and improving the decision-making skills of their clients.

Critical thinking is the leader’s best friend when it comes to decision-making. This outer-core leadership competency allows you to rise above the fray, eliminate distractions, recognize mistakes, and draw the correct conclusions.

Back to blog

MORE DETAILS COMING SOON

Catch These Benefits! 13 Examples of Critical Thinking in the Workplace

Max 8 min read

Click the button to start reading

Your team is dealing with a sudden decrease in sales, and you’re not sure why.

When this happens, do you quickly make random changes and hope they work? Or do you pause, bring your team together , and analyze the problem using critical thinking?

In the pages ahead, we’ll share examples of critical thinking in the workplace to show how critical thinking can help you build a successful team and business.

Ready to make critical thinking a part of your office culture?

Let’s dive in!

What Is Critical Thinking? A Quick Definition

Critical thinking is the systematic approach of being a sharp-minded analyst. It involves asking questions, verifying facts, and using your intellect to make decisions and solve problems.

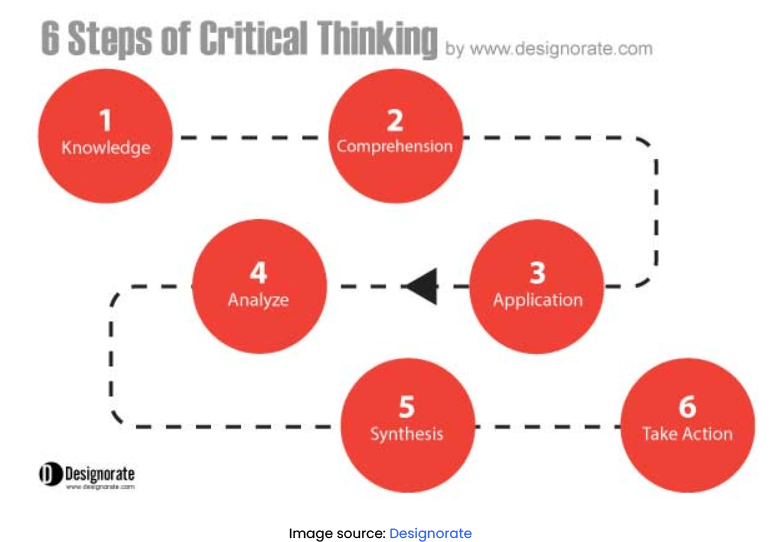

The process of thinking critically is built upon a foundation of six major steps:

- Comprehension

- Application

- Creation/Action

First, you gather “knowledge” by learning about something and understanding it. After that, you put what you’ve learned into action, known as “application.” When you start looking closely at the details, you do the “analysis.”

After analyzing, you put all those details together to create something new, which we call “synthesis.” Finally, you take action based on all your thinking, and that’s the “creation” or “action” step.

Examples of Critical Thinking in the Workplace

Even if the tasks are repetitive, or even if employees are required to follow strict rules, critical thinking is still important. It helps to deal with unexpected challenges and improve processes.

Let’s delve into 13 real examples to see how critical thinking works in practice.

1. Evaluating the pros and cons of each option

Are you unsure which choice is the best? Critical thinking helps you look at the good and bad sides of each option. This ensures that you make decisions based on facts and not just guesses.

Product development : For example, a product development team is deciding whether to launch a new product . They must evaluate the pros and cons of various features, production methods, and marketing strategies to make an informed decision. Obviously, the more complete their evaluation is, the better decisions they can make.

2. Breaking down complex problems into smaller, manageable parts

In the face of complex problems, critical thinkers are able to make the problem easier to solve. How? They create a step-by-step process to address each component separately.

Product deliveries and customer support . Imagine you work in a customer service department, and there has been a sudden increase in customer complaints about delayed deliveries. You need to figure out the root causes and come up with a solution.

So, you break down the problem into pieces – the shipping process, warehouse operations, delivery routes, customer communication, and product availability. This helps you find out the major causes, which are:

- insufficient staff in the packaging department, and

- high volume of orders during specific weeks in a year.

So, when you focus on smaller parts, you can understand and address each aspect better. As a result, you can find practical solutions to the larger issue of delayed deliveries.

3. Finding, evaluating and using information effectively

In today’s world, information is power. Using it wisely can help you and your team succeed. And critical thinkers know where to find the right information and how to check if it’s reliable.

Market research : Let’s say a marketing team is conducting market research to launch a new product. They must find, assess, and use market data to understand customer needs, competitor tactics, and market trends. Only with this information at hand can they create an effective marketing plan.

4. Paying attention to details while also seeing the bigger picture

Are you great at noticing small things? But can you also see how they fit into the larger picture? Critical thinking helps you do both. It’s like zooming in and out with a camera. Why is it essential? It helps you see the full story and avoid tunnel vision.

Strategic planning . For instance, during strategic planning, executives must pay attention to the details of the company’s financial data, market changes, and internal potential. At the same time, they must consider the bigger picture of long-term goals and growth strategies.

5. Making informed decisions by considering all available information

Ever made a choice without thinking it through? Critical thinkers gather all the facts before they decide. It ensures your decisions are smart and well-informed.

Data analysis . For example, data analysts have to examine large datasets to discover trends and patterns. They use critical thinking to understand the significance of these findings, get useful insights, and provide recommendations for improvement.

6. Recognizing biases and assumptions

Too many workplaces suffer from unfair and biased decisions. Make sure yours isn’t on this list. Critical thinkers are self-aware and can spot their own biases. Obviously, this allows them to make more objective decisions.

Conflict resolution . Suppose a manager needs to mediate a conflict between two team members. Critical thinking is essential to understand the underlying causes, evaluate the validity of each person’s opinion, and find a fair solution.

Hiring decisions . Here’s another example. When hiring new employees, HR professionals need to critically assess candidates’ qualifications, experience, and cultural fit. At the same time, they have to “silence” their own assumptions to make unbiased hiring decisions.

7. Optimizing processes for efficiency

Critical thinking examples in the workplace clearly show how teams can improve their processes.

Customer service . Imagine a company that sells gadgets. When customers have problems, the customer service team reads their feedback. For example, if many people struggle to use a gadget, they think about why that’s happening. Maybe the instructions aren’t clear, or the gadget is too tricky to set up.

So, they work together to make things better. They make a new, easier guide and improve the gadget’s instructions. As a result, fewer customers complain, and everyone is happier with the products and service.

8. Analyzing gaps and filling them in

Discovering problems in your company isn’t always obvious. Sometimes, you need to find what’s not working well to help your team do better. That’s where critical thinking comes in.

Training and development . HR professionals, for instance, critically analyze skill gaps within the organization to design training programs. Without deep analysis, they can’t address specific needs and upskill their employees .

9. Contributing effectively to team discussions

In a workplace, everyone needs to join meetings by saying what they think and listening to everyone else. Effective participation, in fact, depends on critical thinking because it’s the best shortcut to reach collective decisions.

Team meetings . In a brainstorming session, you and your colleagues are like puzzle pieces, each with a unique idea. To succeed, you listen to each other’s thoughts, mix and match those ideas, and together, you create the perfect picture – the best plan for your project.

10. Contributing effectively to problem-solving

Effective problem-solving typically involves critical thinking, with team members offering valuable insights and solutions based on their analysis of the situation.

Innovative SaaS product development . Let’s say a cross-functional team faces a challenging innovation problem. So, they use critical thinking to brainstorm creative solutions and evaluate the feasibility of each idea. Afterwards, they select the most promising one for further development.

11. Making accurate forecasts

Understanding critical thinking examples is essential in another aspect, too. In fact, critical thinking allows companies to prepare for what’s coming, reducing unexpected problems.

Financial forecasting . For example, finance professionals critically assess financial data, economic indicators, and market trends to make accurate forecasts. This data helps to make financial decisions, such as budget planning or investment strategies.

12. Assessing potential risks and recommending adjustments

Without effective risk management , you’ll constantly face issues when it’s too late to tackle them. But when your team has smart thinkers who can spot problems and figure out how they might affect you, you’ll have no need to worry.

Compliance review . Compliance officers review company policies and practices to ensure they align with relevant laws and regulations. They want to make sure everything we do follows the law. If they find anything that could get us into trouble, they’ll suggest changes to keep us on the right side of the law.

13. Managing the crisis

Who else wants to minimize damage and protect their business? During a crisis, leaders need to think critically to assess the situation, make rapid decisions, and allocate resources effectively.

Security breach in a big IT company . Suppose you’ve just discovered a major security breach. This is a crisis because sensitive customer data might be at risk, and it could damage your company’s reputation.

To manage this crisis, you need to think critically. First, you must assess the situation. You investigate how the breach happened, what data might be compromised, and how it could affect your customers and your business. Next, you have to make decisions. You might decide to shut down the affected systems to prevent further damage. By taking quick, well-planned actions, you can minimize the damage and protect your business.

Encouraging Critical Thinking in Your Team: A Brief Manager’s Guide

According to Payscale’s survey, 60% of managers believe that critical thinking is the top soft skill that new graduates lack. Why should you care? Well, among these graduates, there’s a good chance that one could eventually become a part of your team down the road.

So, how do you create a workplace where critical thinking is encouraged and cultivated? Let’s find out.

Step 1: Make Your Expectations Clear

First things first, make sure your employees know why critical thinking is important. If they don’t know how critical it is, it’s time to tell them. Explain why it’s essential for their growth and the company’s success.

Step 2: Encourage Curiosity

Do your employees ask questions freely? Encourage them to! A workplace where questions are welcomed is a breeding ground for critical thinking. And remember, don’t shut down questions with a “That’s not important.” Every question counts.

Step 3: Keep Learning Alive

Encourage your team to keep growing. Learning new stuff helps them become better thinkers. So, don’t let them settle for “I already know enough.” Provide your team with inspiring examples of critical thinking in the workplace. Let them get inspired and reach new heights.

Step 4: Challenge, Don’t Spoon-Feed

Rethink your management methods, if you hand your employees everything on a silver platter. Instead, challenge them with tasks that make them think. It might be tough, but don’t worry. A little struggle can be a good thing.

Step 5: Embrace Different Ideas

Do you only like ideas that match your own? Well, that’s a no-no. Encourage different ideas, even if they sound strange. Sometimes, the craziest ideas lead to the best solutions.

Step 6: Learn from Mistakes

Mistakes happen. So, instead of pointing fingers, ask your employees what they learned from the mistake. Don’t let them just say, “It’s not my fault.”

Step 7: Lead the Way

Are you a critical thinker yourself? Show your employees how it’s done. Lead by example. Don’t just say, “Do as I say!”

Wrapping It Up!

As we’ve seen, examples of critical thinking in the workplace are numerous. Critical thinking shows itself in various scenarios, from evaluating pros and cons to breaking down complex problems and recognizing biases.

The good news is that critical thinking isn’t something you’re born with but a skill you can nurture and strengthen. It’s a journey of growth, and managers are key players in this adventure. They can create a space where critical thinking thrives by encouraging continuous learning.

Remember, teams that cultivate critical thinking will be pioneers of adaptation and innovation. They’ll be well-prepared to meet the challenges of tomorrow’s workplace with confidence and competence.

#ezw_tco-2 .ez-toc-title{ font-size: 120%; ; ; } #ezw_tco-2 .ez-toc-widget-container ul.ez-toc-list li.active{ background-color: #ededed; } Table of Contents

Manage your remote team with teamly. get your 100% free account today..

PC and Mac compatible

Teamly is everywhere you need it to be. Desktop download or web browser or IOS/Android app. Take your pick.

Get Teamly for FREE by clicking below.

No credit card required. completely free.

Teamly puts everything in one place, so you can start and finish projects quickly and efficiently.

Keep reading.

7 Relatable Examples of Social Loafing You’ve Definitely Experienced

7 Relatable Examples of Social Loafing You’ve Definitely ExperiencedHave you ever been part of a group project where some people didn’t seem to be putting in the same effort? Well, it turns out there’s a psychological phenomenon for that… It’s called social loafing, and it refers to the tendency of team members to put forth …

Continue reading “7 Relatable Examples of Social Loafing You’ve Definitely Experienced”

Productivity

Manage Your Calendar Like A Pro

Manage Your Calendar Like A ProThere isn’t a more widely used and recognized productivity tool than the calendar. People use calendars for all sorts of purposes including the planning of daily activities, remembering birthdays, and scheduling meetings… just to name a few! There is no one size fits all system to manage your calendar but …

Continue reading “Manage Your Calendar Like A Pro”

Max 19 min read

Making a Difference Together: How Societal Marketing Drives Meaningful Change

Making a Difference Together: How Societal Marketing Drives Meaningful ChangeAre you seeking to understand societal marketing, or are you interested in making a difference in the world through responsible business practices? Regardless of your motivation, you’ve come to the right place. Societal marketing is a powerful approach that balances consumer needs, company profits, and the …

Continue reading “Making a Difference Together: How Societal Marketing Drives Meaningful Change”

Max 6 min read

Project Management Software Comparisons

Asana vs Wrike

Basecamp vs Slack

Smartsheet vs Airtable

Trello vs ClickUp

Monday.com vs Jira Work Management

Trello vs asana.

Get Teamly for FREE Enter your email and create your account today!

You must enter a valid email address

You must enter a valid email address!

Why critical thinking is crucial in HR

Imagine a conflict between two employees in a team. The conflict escalates, and begins to affect the overall productivity and morale of the team. The human resources manager now has to intervene and find a solution that resolves the disagreement and also restores harmony in the team.

In such a scenario, critical thinking becomes crucial for HR professionals. Instead of jumping to conclusions or relying solely on personal biases, they will have to approach the situation with a thoughtful and analytical mindset. Thinking critically, they will gather relevant information by speaking to both parties involved, as well as other team members who may have witnessed the conflict. They will analyse the situation without any prejudices and consider different perspectives.

Generally, critical thinking is important for everyone, but its significance in HR is crucial. After all, critical thinking is the skill of carefully examining and assessing arguments and beliefs using logic and a systematic approach. It requires questioning assumptions, exploring different viewpoints, scrutinising evidence and making thoughtful and reasoned conclusions.

This rational way of thinking helps HR personnel navigate complexities and ensures that they make informed choices that benefit both employees and the company.

“Humans are thinking animals. Therefore, while dealing with them at the workplace, HR managers should take an empathetic yet rational decision-making approach to ensure unbiasedness.” Rishav Dev, former CHRO, Noveltech Feeds

Tackling diverse workplace situations

Underscoring the vital importance of critical thinking in HR, Sharad Verma, VP & CHRO, Iris Software, highlights various aspects of this primarily problem-solving exercise, including the ability to distinguish between facts and opinions, making logical conclusions based on data, finding the root cause of the problem and establishing cause-effect relationship. “These competencies equip HR professionals to tackle diverse workplace situations with clarity and insight,” asserts Verma.

Rishav Dev, former CHRO, Noveltech Feeds, opines, “Humans are thinking animals. Therefore, while dealing with them at the workplace, HR managers should take an empathetic yet rational decision-making approach to ensure unbiasedness.”

How to evaluate situations with critical thinking

“Steps in evaluating a situation include cultivating a calm and analytical mindset, collecting relevant data and evidence, seeking input from stakeholders, assessing solution effectiveness, conducting cause-effect analysis and formulating actionable plans for the future to help make sound decisions,” enunciates Verma.

Kamlesh Dangi, group head-HR, InCred, emphasises the compatibility of critical thinking and empathy. Dangi reveals how critical thinking enables HR professionals to overcome bias and make informed decisions.

He says, “By approaching employee cases objectively, relying on factual evidence rather than personal biases, HR practitioners can deliver fair and well-founded solutions.”

“By approaching employee cases objectively, relying on factual evidence rather than personal biases, HR practitioners can deliver fair and well-founded solutions.” Kamlesh Dangi, group head-HR, InCred

Synergy of critical thinking and empathy

By empathising with employee’s challenges and understanding their perspective, an HR professional can critically assess the situation to make a fair and informed decision. A decision that takes into account an individual’s well-being and growth opportunities within the organisation.

So, does critical thinking or analysis affect the empathic aspect of HR? In Dangi’s opinion, “Critical thinking and empathy can coexist, one can analyse a situation based on facts and figures and still be empathetic towards the people involved. Thus, this can foster a deep understanding of others’ perspectives.”

How organisations can promote critical thinking

By creating an environment of open communication, organisations can empower HR teams to approach challenges with a thoughtful and analytical mindset. This cultivates an HR department that is adept at making well-founded decisions and helps drive organisational growth.

Dangi suggests, “To foster critical thinking, organisations must raise awareness, provide role models and actively promote the use of assessment tools that empowers the HR to make fact-based decisions.”

“Steps in evaluating a situation include cultivating a calm and analytical mindset, collecting relevant data and evidence, seeking input from stakeholders, assessing solution effectiveness, conducting cause-effect analysis and formulating actionable plans for the future to help make sound decisions.” Sharad Verma, VP & CHRO, Iris Software

Setting clear criteria for decision making

Establishing clear criteria for hiring and firing decisions in the organisation helps professionals make decisions based on precise data and information.

“Defining qualifications, experience and role suitability allows HR professionals to assess candidates objectively,” points out Dangi.

This approach ensures that decisions are based on pure evidence rather than subjective feelings, resulting in fair and informed choices that align with organisational requirements.

If HR practitioners or managers do not apply critical thinking and make decisions based on their biases or gut feelings, then it can affect the organisation’s credibility and level of integrity.

In this ever-evolving HR landscape, embracing critical thinking can help HR professionals navigate challenges with clarity, objectivity and empathy in a profound and inclusive manner, benefiting the organisation and the people who rely on their decisions.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please enter an answer in digits: nineteen + eight =

Related Posts

Manipalcigna health insurance gets richa chatterjee as chro, indian nurse in britain gets interim relief; £17,000 pounds in unpaid wages, jabil’s rs 2000 cr. plant will generate 5000 jobs in trichy, why ‘culture add’ outshines ‘culture fit’.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Evidence-based HR: Make better decisions and step up your influence

A step-by-step approach to using evidence-based practice in your decision-making

People professionals are often involved in solving complex organisational problems and need to understand ‘what works’ in order to influence key organisational outcomes. The challenge is to pick reliable, trustworthy solutions and not be distracted by unreliable fads, outdated received wisdom or superficial quick fixes.

This challenge has led to evidence-based practice . The goal is to make better, more effective decisions to help organisations achieve their goals.

At the CIPD, we believe this is an important step for the people profession to take: our Profession Map describes a vision of a profession that is principles-led, evidence-based and outcomes-driven.

This guide sets out what evidence-based practice is, why it’s important, what evidence we should use and how the step-by-step approach works. It builds on previous CIPD publications 1 and the work of the Center for Evidence-Based Management ( CEBMa ), as well as our experience of applying an evidence-based approach to the people profession.

What is evidence-based practice?

Why do we need to be evidence-based, what evidence should we use, how do we make evidence-based decisions, how to move towards an evidence-based profession, notes and further reading, acknowledgements and publication information, evidence-based practice: a video introduction.

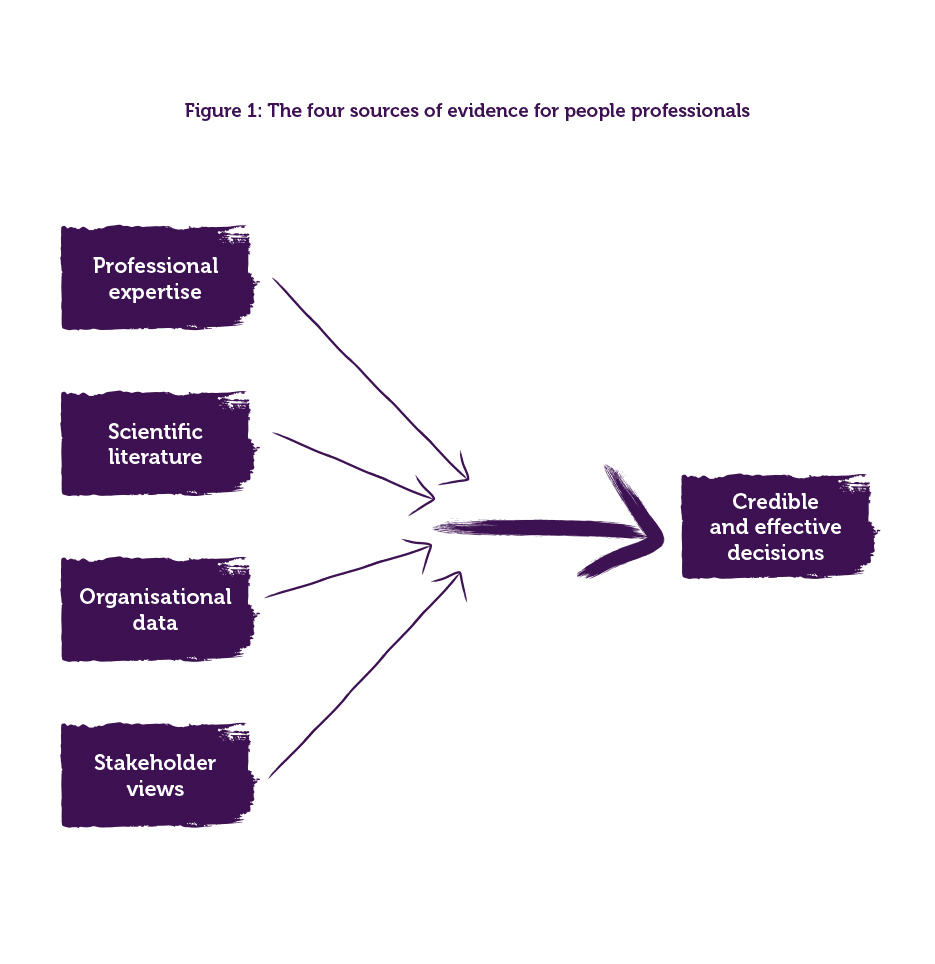

The basic idea of evidence-based practice is that high-quality decisions and effective practices are based on critically appraised evidence from multiple sources. When we say ‘evidence’, we mean information, facts or data supporting (or contradicting) a claim, assumption or hypothesis. This evidence may come from scientific research, the local organisation, experienced professionals or relevant stakeholders. We use the following definition from CEBMa :

“Evidence-based practice is about making decisions through the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of the best available evidence from multiple sources… to increase the likelihood of a favourable outcome.”

This technical definition is worth unpacking.

Conscientious means that you make a real effort to gather and use evidence from multiple sources – not just professional opinion. Good decisions will draw on evidence from other sources as well: the scientific literature, the organisation itself, and the judgement of experienced professionals.

Explicit means you take a systematic, step-by-step approach that is transparent and reproducible – describing in detail how you acquired the evidence and how you evaluated its quality. In addition, in order to prevent cherry-picking, you make explicit the criteria you used to select the evidence.

Judicious means critically appraised. Evidence-based practice is not about using all the evidence you can find, but focuses only on the most reliable and trustworthy evidence.

Increased likelihood means that taking an evidence-based approach does not guarantee a certain outcome. Evidence-based people professionals typically make decisions not based on conclusive, solid evidence, but on probabilities, indications and tentative conclusions. As such, an evidence-based approach does not tell you what to decide, but it does help you to make a better-informed decision.

The importance of evidence-based practice and the problems it sets out to solve is explained in more detail in our factsheet and thought leadership article but, in essence, it has three main benefits:

- It ensures that decision-making is based on fact, rather than outdated insights, short-term fads and natural bias.

- It creates a stronger body of knowledge and as a result, a more trusted profession.

- It gives more gravitas to professionals, leads to increased influence on other business leaders and has a more positive impact in work.

Before making an important decision or introducing a new practice, an evidence-based people professional should start by asking: "What is the available evidence?" As a minimum, people professionals should consider four sources of evidence.

Evidence from people professionals

The expertise and professional judgement of practitioners, such as colleagues, managers, staff members, employees and leaders, is vital for determining whether a people management issue does require attention, if the data from the organisation are reliable, whether research findings are applicable, or whether a proposed solution or practice is likely to work given the organisational context.

Evidence from scientific literature

In past decades, a large number of scientific studies have been published on topics relevant to people professionals, for example on topics such as the characteristics of effective teams, the drivers of knowledge worker performance, the recruitment and selection of personnel, the effect of feedback on employee performance, the antecedents of absenteeism, and the predictors of staff turnover. Empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals are especially relevant, as they provide the strongest evidence on cause-and-effect relationships, and thus what works in practice.

Evidence from the organisation

This can be financial data or performance indicators (for example, number of sales, costs, return on investment, market share), but it can also come from customers (for example, customer satisfaction, brand recognition), or employees (for example, task performance, job satisfaction). It can be ‘hard’ numbers such as staff turnover rates, medical errors or productivity levels, but it can also include ‘soft’ elements such as perceptions of the organisation’s risk climate or attitudes towards senior management. This source of evidence typically helps leaders identify the existence or scale of a need or problem, possible causes and potential solutions.

Evidence from stakeholders

Stakeholders are people (individuals or groups inside or outside the organisation) whose interests affect or are affected by a decision and its outcomes. For example, internal stakeholders such as employees can be affected by the decision to reduce the number of staff, or external stakeholders such as suppliers may be affected by the decision to apply higher-quality standards. However, stakeholders can also influence the outcome of a decision; for example, employees can go on strike, regulators can block a merger, and the general public can stop buying a company’s products. For this reason, this evidence is often an important guide to what needs or issues an organisation investigates, what improvements it considers and whether any trade-offs or unintended consequences of proposed interventions are acceptable.

The importance of combining all sources

Finally, none of the four sources are enough on their own – every source of evidence has its limitations and its weaknesses. It may not always be practical to draw on all four sources of evidence or to cover each of them thoroughly, but the more we can do, the better decisions will be.

Since the 1990s, evidence-based practice has become an established standard in many professions. The principles and practices were first developed in the field of medicine and following this, have been applied in a range of professions – including architecture, agriculture, crime and justice, education, international development, nutrition and social welfare, as well as management. Despite differing contexts, the approach broadly remains the same.

Below, each step is discussed and illustrated with examples. It is important to note that following all six steps will not always be feasible. However, the more that professionals can do – especially when making major or strategic decisions – the better.

Asking questions to clarify the problem and potential solution and to check whether there is evidence in support of that problem and solution is an essential first step. Without these questions the search for evidence will be haphazard, the appraisal of the evidence arbitrary, and its applicability uncertain.

Asking critical questions should be constructive and informative. It is not about tearing apart or dismissing other people's ideas and suggestions. By the same token, evidence-based practice is not an exercise in myth busting, but rather seeking to establish whether claims are likely to be true and potential solutions are likely to be effective.

Example 1 shows the type of questions you can ask.

Example 1: Autonomous teams – an example of asking critical questions

Consider a typical starting point: a senior manager asks you to develop and implement autonomous teams in the organisation. Rather than jumping into action and implementing the proposed solution, an evidence-based approach first asks questions to clarify the (assumed) problem:

- What is the problem we are trying to solve with autonomous teams?

- How do we know we have this problem? What is the evidence?

- What are the organisational consequences of this problem?

- How serious and how urgent is this problem? What happens if we do nothing?

The next step would be to ask more specific questions on whether there is sufficient evidence confirming the existence and seriousness of the problem. The senior manager explains that the organisation has a serious problem with absenteeism, and that a lack of autonomy – employees’ discretion and independence to schedule their work and determine how it is to be done – is assumed to be its major cause. Important questions to ask are:

- Do experienced practitioners (for example, supervisors, managers) agree we have a serious problem with absenteeism? Do they agree lack of autonomy is a major cause?

- Do the organisational data confirm we have a problem with absenteeism? How does our rate of absenteeism compare to the average in the sector? Is there a trend? Do the data suggest the problem will increase when nothing is done?

- Does the scientific literature confirm that lack of autonomy is an important driver of absenteeism? What are other common causes?

- How do stakeholders (for example, employees, supervisors) feel about the problem? Do they agree lack of autonomy is a major cause?

Based on the answers, you should be able to conclude whether there is sufficient evidence to support the senior manager’s claim that the organisation has a problem with absenteeism, and that this problem is most likely caused by a lack of autonomy. If one or more questions can’t be answered, this may be an indication that more evidence is needed. The next step would be to ask the executive manager critical questions about the proposed solution:

- Do we have a clear idea of what autonomous teams are? How are they different from ‘traditional’ teams?

- How exactly are autonomous teams supposed to have a positive effect on absenteeism? How does this work? What is the causal mechanism/logic model?

The final step would be to ask questions to check whether there is sufficient evidence from multiple sources indicating the proposed solution will indeed solve the problem:

- Do experienced practitioners (for example, supervisors, managers) agree that the introduction of autonomous teams is the ’best’ solution to lower the organisation’s absenteeism rate? Do they see downsides or unintended negative consequences? Do they see alternative solutions that may work better?

- Can organisational data be used to monitor the impact of autonomous teams on absenteeism?

- Does the scientific literature confirm that autonomous teams have a positive effect on absenteeism? Does the literature suggest other solutions that may work better?

- How do stakeholders (for example, employees, supervisors) feel about the introduction of autonomous teams? Do they think it will have a positive impact on absenteeism?

Based on the answers to the questions in Step 1 , we should have a good understanding of whether there is sufficient evidence from multiple sources to support the assumed problem and preferred solution. In most cases, however, the available evidence is too limited or important sources are missing. In that case, we proceed with the second step of evidence-based practice: acquiring evidence.

Acquiring evidence from practitioners

This could be through:

- face-to-face conversations: this is the easiest way. While it can be prone to bias, sometimes simply asking people about their experience can give good insight.

- more structured interactive group meetings, workshops or other ways of collecting views, such as surveys.

Practitioner expertise is a useful starting point in evidence-based practice to understand the assumed problem and preferred solutions. It is also helpful in interpreting other sources of evidence – for example, in assessing whether insights from scientific literature are relevant to the current context.

Acquiring evidence from scientific literature

This could be through the following types of publication:

- Peer-reviewed academic journals, which can be found in research databases. These are usually behind a paywall or are accessible only through a university, but CIPD members have access to one such database in EBSCO's Discovery Service . It is also worth noting that different databases focus on different specialisms – for example, like the Discovery Service, EBSCO's more expansive Business Source Elite and ProQuest's ABI/INFORM cover business and management in general, whereas the APA's PsychINFO focuses on psychology (these are all available via CEBMa ). However, even once you access them, peer-reviewed articles often contain theoretical and technical information that's hard to understand for non-researchers.

- ‘Evidence reviews’ such as systematic reviews (see below) and shorter rapid evidence assessments (REAs). These are easier to use as they aim to identify and summarise the most relevant studies on a specific topic. They also do the work of identifying the best research, and selecting and critically appraising studies on the basis of explicit criteria. The CIPD produces evidence reviews on a range of HR and L&D topics – you can access these via our Evidence review hub .

Acquiring evidence from the organisation

This could be through the following sources:

- Internal management information: Often the finance department and the HR/personnel department are the key custodians of people data and analytics.

- Internal research and evaluation: This could be conducted via trials of interventions, bespoke surveys or focus groups.

- External sources such as census bureaus, industry bodies, professional associations and regulators. However, sometimes relevant organisational data is not available, either because collecting it is too time-consuming and costly, because of data sensitivities and a lack of disclosure (for example on employee diversity ), or simply due to a lack of analytical capability in processing and interpreting data.

Acquiring evidence from stakeholders

Organisational decisions often have lots of stakeholders both inside and outside the organisation. A stakeholder map is therefore a useful tool to identify which stakeholders are the most relevant. A stakeholder’s relevance is determined by two variables:

- The extent to which the stakeholder’s interests are affected by the decision (harms and benefits).

- The extent to which the stakeholder can affect the decision (power to influence).

When the most important stakeholders are identified, often qualitative methods such as focus groups and in-depth interviews are used to discuss their concerns.

Unfortunately, evidence is never perfect and can be misleading in many different ways. Sometimes the evidence is so weak that it is hardly convincing at all, while at other times the evidence is so strong that no one doubts its correctness. After we have acquired the evidence we therefore need to critically appraise what evidence is ‘best’ – that is, the most trustworthy.

Appraising evidence from practitioners

When appraising the evidence from practitioners, the first step is to determine whether their insights and opinions are based on relevant experience or personal opinions. Next, we need to determine how valid and reliable that experience is. We can assess this by considering:

- whether the experience concerns repeated experience

- whether the situation allowed for direct, objective feedback

- whether the experience was gained within a regular, predictable work environment.

For example, based on these three criteria, it can be determined that the expertise of a sales agent is more likely to be trustworthy than the expertise of a business consultant specialised in mergers. In general, sales agents work within a relatively steady and predictable work environment, they give their sales pitch several times a week, and they receive frequent, direct and objective feedback. Consultants, however, are involved in a merger only a few times a year (often less), so there are not many opportunities to learn from experience. In addition, the outcome of a merger is often hard to determine – what is regarded as a success by one person may be seen as a failure by another. Finally, consultants accompanying a merger do not typically operate in a regular and predictable environment: contextual factors such as organisational differences, power struggles and economic developments often affect the outcome.

Professional expertise that is not based on valid and reliable experience is especially prone to bias, but any evidence from practitioners is likely to reflect personal views and be open to bias (see Building an evidence-based people profession ). For this reason, we should always ask ourselves how a seemingly experienced professional’s judgement could be biased and always look at it alongside other evidence.

Appraising evidence from scientific literature

Appraising scientific evidence requires a certain amount of research understanding. To critically appraise findings from scientific research, we need to understand a study’s ‘design’ (the methods and procedures used to collect and analyse data). Examples of common study designs are cross-sectional studies (surveys), experiments (such as randomised controlled trials, otherwise known as ‘RCTs’), qualitative case studies, and meta-analyses. The first step is to determine whether a study’s design is the best way to answer the research question. This is referred to as ‘methodological appropriateness’.

Different types of research questions occur in the domain of people management. Very often we are concerned with ‘cause-and-effect’ or ‘impact’ questions, for example:

- What works in managing effective virtual teams?

- Does digital work affect mental wellbeing?

- How can managers help employees be more resilient?

- What makes goal setting and feedback more effective in improving performance?

The most appropriate study designs to answer cause-and-effect questions are RCTs and controlled before-after studies, along with systematic reviews and meta-analyses that gather together these types of study.

Other research questions that are relevant to people professionals are questions about prevalence (for example, “How common is burnout among nurses in hospitals?”), attitudes (for example, “How do employees feel about working in autonomous teams?”), prediction (for example, “What are drivers/predictors of absenteeism?”) or differences (for example, “Is there a difference in task performance between virtual teams and traditional teams?”).

Each of these questions would ideally have a specific study design to guarantee a valid and reliable (non-biased) answer.

An overview of common study designs and what they involve can be found in the Appendix . Following this (also in the Appendix) is an overview of types of questions and the appropriateness of each design. This gives a useful guide for both designing and appraising studies. For example, if you want information on how prevalent a problem is, a survey will work best; a qualitative study will give the greatest insight into people’s experiences of, or feelings about, the problem; and an RCT or before-after study will give the best information on whether a solution to the problem has the desired impact.

Of course, which design a study uses to answer a research question is not the only important aspect to consider. The quality of the study design – how well it was conducted – is equally important. For example, key considerations in quantitative studies include how participants are selected and whether measures are reliable and valid. 2 For systematic reviews and meta-analyses, a key question is how included studies are selected.

Finally, if an impact study seems to be trustworthy, we want to understand what the impact is of the intervention or factor being studied. Statistical measures of ‘effect sizes’ give us this information, both for an intervention or factors of influence itself, and how it compares to others. Being able to compare effect sizes is very important for practice. For example, the critical question is not simply, “Does a new management practice have a small or large effect on performance?” but rather, “Is this the best approach or are other practices more impactful?” For more information on effect sizes, see Effects sizes and interpreting research findings in the Appendix .

Appraising evidence from the organisation

When critically appraising evidence from the organisation, the first thing to determine is whether the data are accurate. Nowadays, many organisations have advanced management information systems that present metrics and KPIs in the form of graphs, charts and appealing visualisations, giving the data a sense of objectivity. However, the data in such systems are often collected by people, which is in fact a social and political endeavour. An important appraisal question therefore is: “Were the data collected, processed and reported in a reliable way?”

In addition to the accuracy of data, several other factors can affect its trustworthiness, such as measurement error, missing contextual information and the absence of a logic model. Some organisations use advanced data-analytic techniques that involve big data, artificial intelligence or machine learning. Big data and AI technology often raise serious social, ethical and political concerns as these techniques are based on complex mathematical algorithms that can have hidden biases and, as a result, may introduce gender or racial biases into the decision-making process.

Appraising evidence from stakeholders

Unlike the scientific literature and organisational data, which serve to give objectifiable and trustworthy insights, stakeholder evidence concerns subjective feelings and perceptions that can’t be considered as facts. Nonetheless, we can make sure that stakeholder evidence comes from a representative sample, so that it is an accurate reflection of all relevant stakeholders.

Evidence-based practitioners should present stakeholders with a clear view of the other sources of evidence. That is, they should summarise what the body of published research and organisational data tell us, as viewed with the benefit of professional knowledge. This can serve as the basis for a well-informed and meaningful two-way exchange. For example, the scientific literature may point to a certain solution being most effective, but stakeholders may advise on other important aspects that should be weighed up against this evidence – for example, whether the intervention is difficult to implement, ethically questionable or too expensive.

Use the best available evidence

The purpose of critical appraisal is to determine which evidence is the best available – that is, the most trustworthy. Sometimes, the quality of the evidence available is less than ideal; for example, there may not be any randomised controlled trials on your intervention of interest. But this does not leave us empty-handed. We can look at other studies that are less trustworthy but still go some way to showing cause-and-effect. Indeed, it’s possible that the best available evidence on an important question is the professional experience of a single colleague. However, even this limited evidence can still lead to a better decision than not using it, as long as we are aware of and open about its limitations. A useful maxim is that “the perfect is the enemy of the good”: if you don’t have the ideal evidence, you can still be evidence-based in how you make decisions.

After we have acquired and critically appraised the different types of evidence, how should we bring them all together? The broad process of knitting together evidence from multiple sources is more craft than science. It should be based on the question you wish to answer and the resources available.

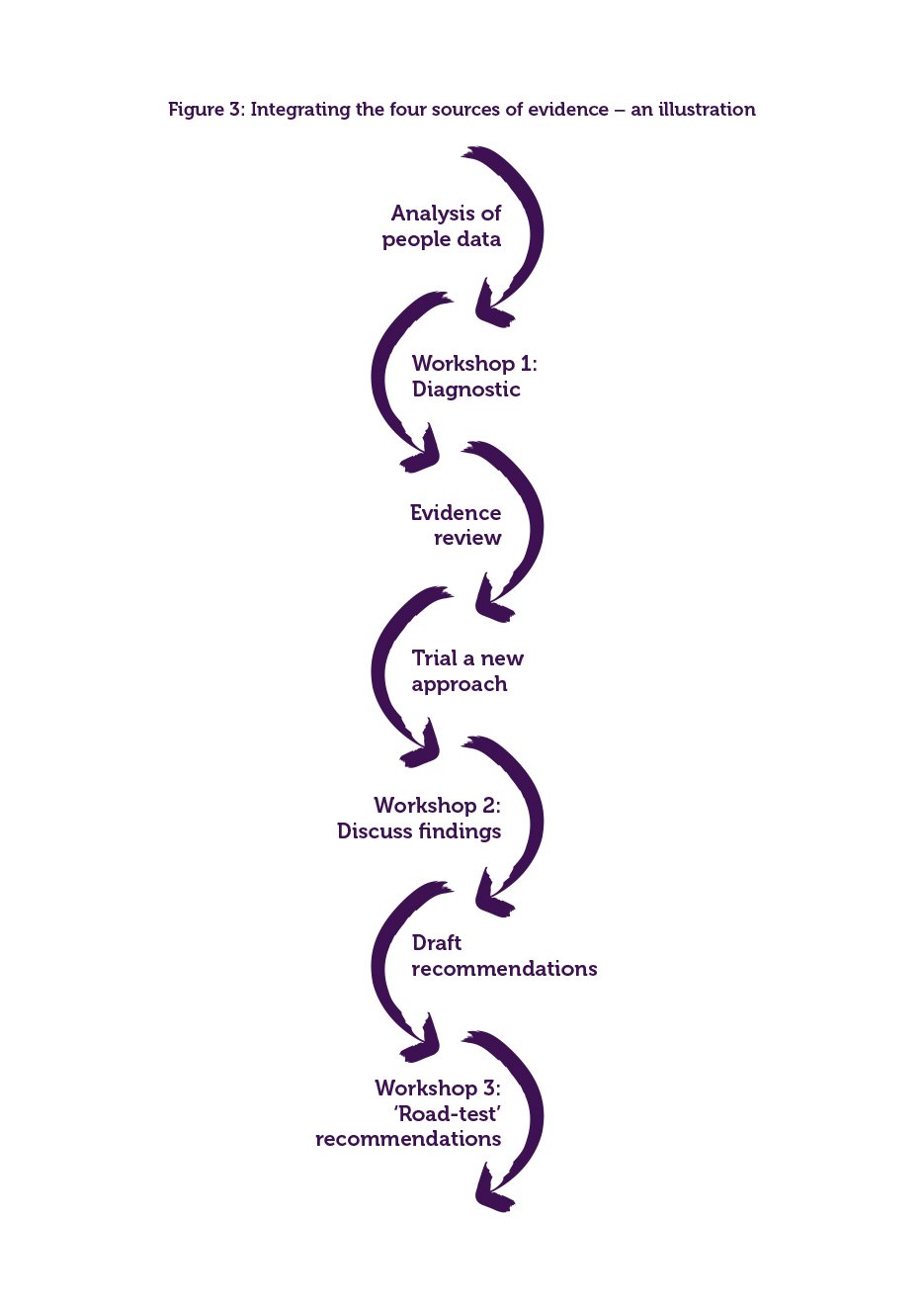

A potential approach is illustrated in Figure 3 below. The steps illustrated here are as follows:

- The starting point is evidence from the organisation in the form of people data; for example, let’s say employee survey results and key performance indicators have identified a likely problem.

- This evidence informs the next phase: workshop or roundtable discussions with practitioner experts and stakeholders on issues the organisation faces.

- Once there is agreement on the priority issues, the project managers scope researchable questions, which are examined in an evidence review of the published scientific literature.

- The review finds little research on a practice of particular interest, so to fill the evidence gap, researchers run an in-house trial.

- The findings of this pilot are presented to practitioner experts and stakeholders, discussing with them the implications for practice.

- All the sources of evidence, including expert and stakeholder views, are then brought together into a final report with recommendations.

- These are presented and discussed with stakeholders in a final workshop.

In most cases, the answer as to whether to implement a new practice is not a simple yes or no. Questions to consider include the following:

- Does the evidence apply to our organisational context?

- Is the intervention in question the most effective or are others more effective?

- Are the anticipated benefits likely to outweigh any risks?

- Are there ethical issues to consider; for example, if the benefits aren't evenly distributed among shareholders?

- Do the costs, necessary resources and timescale fit the organisation’s needs?

The final part of this step concerns how, and in what form, the evidence should be applied. This includes the following possible approaches:

- The 'push' approach: Actively distributing the evidence to the organisation’s relevant stakeholders, often in the form of a protocol, guideline, checklist or standard operating procedure. The push approach is typically used for operational, routine practices (for example, hiring and selection procedures, or how to deal with customer complaints).

- The 'pull' approach: Evidence from multiple sources is actively obtained and succinctly summarised. When it concerns summarising findings from the scientific literature, rapid evidence assessments (REAs) are often used – see Step 2 and the CIPD Evidence review hub . The pull approach is typically used for non-routine decisions that involve making changes to the way an organisation operates (for example, the implementation of an autonomous team, or the introduction of performance feedback).

- The 'learn by doing' approach: Pilot testing and systematically assessing outcomes of the decisions we take in order to identify what works (see also Step 6 ). This is especially appropriate if there is no other option, for novel or hyper-complex decisions when evidence is often not (yet) available (for example, starting a new business in an emerging market).

The final step of evidence-based practice is assessing the outcome of the decision taken: did the decision (or the implementation of the new practice) deliver the desired results?

Unfortunately, organisations seldom evaluate the outcome of decisions, projects or new practices. Nevertheless, assessing the outcome of our decisions is something we can and always should do. Before we assess the outcome, however, we first need to determine:

- whether the decision or new practice was executed/implemented

- whether it was executed/implemented as planned.

After all, if we don’t know with certainty if a practice was implemented as planned, we don’t know whether a lack of impact is due to poor implementation or the practice itself.

When we assess the outcome of a decision, we are asking whether the decision had an effect on a particular outcome. As discussed in Step 3 , for a reliable answer to a cause-and-effect question, we need a control group (preferably randomised), a baseline measurement, and a post-measurement – also referred to as a randomised controlled trial. However, often there is no control group available, which leaves us no other option than to assess the impact of the decision or practice by comparing the baseline with the outcome. This type of assessment is referred to as a before-after measurement.

When we do not (or cannot) obtain a baseline, it is harder to reliably assess the outcome of a new practice or intervention. This is often the case in large-scale interventions or change projects that have multiple objectives. But even in those cases, assessing the outcome retrospectively is still beneficial. For example, a meta-analysis found that retrospective evaluations can increase performance by 25%.

People professionals may be thinking: “How do I follow the six steps if I’m not a qualified researcher?” But evidence-based practice is not about trying to turn practitioners into researchers. Rather, it’s about bringing together complementary evidence from different sources, including research and practice. Some aspects of evidence-based practice are technical, so people professionals may find it useful to work with academics or other research specialists.

For example, it’s unlikely all people professionals in an organisation will need to be highly trained in statistics, but an HR team may benefit from bringing in one or two data specialists, or hiring them for ad hoc projects. Similarly, conducting evidence reviews and running trials requires well-developed research skills – practitioners could either develop these capabilities in-house or bring them in from external researchers. Academics are also usually keen to publish research, so it may not be necessary for practitioners to do much additional work to support this. Events like the CIPD’s annual Applied Research Conference can be a good way for people professionals to develop networks with academic researchers.

A good aim for practitioners themselves is to become a ‘savvy consumer’ of research, understanding enough that one can ask probing questions; for example, about the strength of evidence and the size of impacts. This is underpinned by skills in critical thinking, in particular being clear about what questions are really of interest and what evidence will do the best job of answering those questions.

To develop your knowledge and capability, visit the CIPD’s online course on evidence-based practice or, for more advanced skills, look at CEBMa’s online course .

While it is fair to say that evidence-based practice and HR is still in its infancy compared to some other professions, people professionals can begin with these practical steps to pump prime their decision-making:

- Read research.

- Collect and analyse organisational data.

- Review published evidence.

- Trial new practices.

- Share knowledge.

- Above all, think critically.

Our thought leadership article gives further insight into how the people profession can become more evidence-based.

Evidence-based practice is about using the best available evidence from multiple sources to optimise decisions. Being evidence-based is not a question of looking for ‘proof’, as this is far too elusive. However, we can – and should – prioritise the most trustworthy evidence available. The gains in making better decisions on the ground, strengthening the body of knowledge and becoming a more influential profession are surely worthwhile.

To realise the vision of a people profession that’s genuinely evidence-based, we need to move forward on two fronts:

- We need to make sure that the body of professional knowledge is evidence-based – the CIPD’s Evidence review hub is one way in which we are doing this.

- People professionals need to develop knowledge and capability in evidence-based practice. Resources such as the CIPD Profession map and courses from the CIPD and CEBMa can help. Our case studies demonstrate how people professionals are already using an evidence-based approach to successfully address issues in their organisations.

In applying evidence-based thinking in practice, there are certain tenets to hold onto. For substantial decisions, people professionals should always consider drawing on four sources of evidence: professional expertise, scientific literature, organisational data, and stakeholder views and concerns. It can be tempting to rely on professional judgement, received wisdom and ‘best practice’ examples, and bow to senior stakeholder views. But injecting evidence from the other sources will greatly reduce the chance of bias and maximise your chances of effective solutions.

Published management research is a valuable source of evidence for practitioners that seems to be the most neglected. When drawing on the scientific literature, the two principles of critical appraisal (‘not all evidence is equal’) and looking at the broad body of research on a topic (‘one study is not enough’) stand us in excellent stead. This has clear implications for how we look for, prioritise and assess evidence. A systematic approach to reviewing published evidence goes a long way to reducing bias and giving confidence that we’ve captured the most important research insight.

Becoming a profession worthy of the label ‘evidence-based’ is a long road. We need to chip away over time to see real progress. HR, learning and development, and organisational development are newer to evidence-based practice than other professions, but we can take inspiration from them, for whom it has also been a long road, and be ambitious.

This appendix explains some important technical aspects of appraising scientific research, which is inevitably the trickiest aspect of evidence-based practice for non-researchers. As we note in this guide, most people professionals won’t need to become researchers themselves, but a sensible aim is to become ‘savvy consumers’ of research.

To support this, below we explain four aspects of appraising scientific research:

- The three conditions that show causal relationships.

- Common study designs.

- Assessing methodological appropriateness.

- Interpreting research findings (in particular effect sizes).

We hope that this assists you in developing enough understanding to be able to ask probing questions and apply research insights.

Three conditions to show causal relationships

In HR, people management and related fields, we are often concerned with questions about ‘what works’ or what’s effective in practice. To answer these questions, we need to get as close as possible to establishing cause-and-effect relationships.

Many will have heard the phrase ‘correlation is not causality’ or ‘correlation does not imply causation’. It means that a statistical association between two measures or observed events is not enough to show that one characteristic or action leads to (or affects, or increases the chances of) a particular outcome. One reason is that statistical relationships can be spurious, meaning two things appear to be directly related, but are not.

For example, there is a statistically solid correlation between the amount of ice-cream consumed and the number of people who drown on a given day. But it does not follow that eating ice-cream makes you more likely to drown. The better explanation is that you’re more likely to both eat ice-cream and go swimming (raising your chances of drowning) on sunny days.

So what evidence is enough to show causality? Three key criteria are needed: 3

- Association: A statistical relationship (such as a correlation) between reliable measures of an intervention or characteristic and an important outcome.

- Temporality or prediction: That one of these comes before the other, rather than the other way round. We obtain this from before-and-after measures to show changes over time.

- Other factors (apart from the intervention or influencer of interest) don’t explain the relationship: We obtain this from various things: studying a control group alongside the treatment group to see what would have happened without the intervention (the counterfactual); randomizing the allocation of people to intervention and control to avoid selection bias, and controlling for other relevant factors in the statistical analysis (for example, age, gender or occupation).

Common study designs

Different study designs do better or worse jobs at explaining causal relationships.

Single studies

- Randomised controlled trials (RCTs): Conducted well, these are the ideal method that meets all three criteria for causality. They are often referred to as the ‘gold standard’ of impact studies.

- Quasi-experimental designs: These are a broad group of studies that go some way towards meeting the criteria. While weaker than RCTs, they are often much more practical or ethical to conduct, and can provide good evidence for cause and effect. One example is single-group before-and-after studies. Because these don’t include control groups, we don’t know whether any improvement observed would have happened anyway, but by virtue of being longitudinal they at least show that one thing happens following another.

- Parallel cohort studies: These compare changes in outcomes over time for two groups who are similar in many ways but treated differently in a way that is of interest. Because people are not randomly allocated to the two groups, there is a risk of ‘confounders’ – that is, factors that explain both the treatment and outcomes, and interfere with the analysis. But these studies are still useful as they show change over time for intervention and control groups.

These research designs go much further to show cause-and-effect or prediction than cross-sectional surveys, which only observe variables at one point in time. In survey analysis, statistical relationships could be spurious or the direction of causality could even be the opposite to what you might suppose. For example, a simple correlation between ‘employee engagement’ and performance could exist because engagement contributes to performance, or because being rated as high-performing makes people feel better.