Advertisement

Supported by

BOOKS OF THE TIMES

BOOKS OF THE TIMES; And When She Was Bad She Was . . .

- Share full article

By Michiko Kakutani

- March 7, 2002

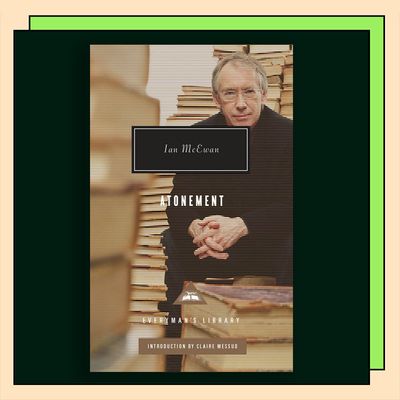

By Ian McEwan

351 pages. Nan A. Talese/ Doubleday. $26.

Ian McEwan's remarkable new novel ''Atonement'' is a love story, a war story and a story about the destructive powers of the imagination. It is also a novel that takes all of the author's perennial themes -- dealing with the hazards of innocence, the hold of time past over time present and the intrusion of evil into ordinary lives -- and orchestrates them into a symphonic work that is every bit as affecting as it is gripping. It is, in short, a tour de force.

The story that ''Atonement'' recounts concerns a monstrous lie told by a 13-year-old girl, a lie that will send her older sister's lover away to jail and that will shatter the family's staid, upper-middle-class existence. As in so many earlier McEwan novels, this shocking event will expose psychological fault lines running through his characters' lives and force them to confront a series of moral choices. It will also underscore the class tensions that existed in England of the 1930's and the social changes wrought by World War II.

At the same time, the novel, supposedly a narrative constructed by one of the characters, stands as a sophisticated rumination on the hazards of fantasy and the chasm between reality and art. Its myriad allusions (to such disparate novels as ''Clarissa,'' ''Northanger Abbey,'' ''Lady Chatterley's Lover,'' ''Howards End'' and ''Mrs. Dalloway'') situate the story within a rich literary context while italicizing the artifice involved in creating a work of fiction -- the tidying up of real-life loose ends made in the service of manufacturing a satisfying tale.

Composed of four very distinct sections, ''Atonement'' begins deceptively, like ''Gosford Park,'' as a sort of English country-house idyll, set down in lambent, Woolfian prose. It is a hot, muggy day in the summer of 1935, and the Tallis family has gathered at the family mansion for a special dinner: the eldest son, Leon, is home for a visit; his sister Cecilia has recently left Cambridge; their 13-year-old sister, Briony, has written a play for Leon's homecoming; and their three Quincey cousins -- 15-year-old Lola and the 9-year-old twins, Jackson and Pierrot -- have arrived for an extended stay.

Already, however, there are portents of disorder. The adults in the household are noticeably absent: Jack Tallis is at his Whitehall office, attending to government business; his wife, Emily, has taken to bed with one of her migraines; and the missing Quincey parents are engaged in an acrimonious divorce. Briony has abandoned plans for her play, after an argument with her cousins. And Cecilia and her Cambridge classmate Robbie Turner, the son of the Tallis family's cleaning woman, have had an intense, sexually charged exchange that results in the breaking of a treasured Meissen vase -- an exchange witnessed by an upset Briony, who once harbored a schoolgirl crush on Robbie.

Many of the events that ensue that night -- including the delivery of an obscene letter, the temporary disappearance of the Quincey twins and the rape of their sister Lola -- sound like the sort of contrived developments found in an old-fashioned Gothic melodrama. But Mr. McEwan does a fluent job of showing how they result from a combination of chance, misunderstanding and malign will, while deftly cutting from one character's perspective to another's to create a complex narrative that is choral in resonance and effect.

In such earlier novels as ''The Innocent'' and ''Amsterdam,'' Mr. McEwan has used his gifts as a writer to put across the point of view of decidedly unsavory characters, and in ''Atonement,'' he manages to make the state of mind that leads Briony to make her false accusations against Robbie plausible, if not sympathetic. He conveys the ways in which her willful naïveté and self-dramatizing imagination lead her to ignore the truth, the ways in which her ignorance about the grown-up world result in a terrible crime -- a crime she will later try to expiate through both rationalization and gestures of atonement.

The subsequent sections of the novel trace the fallout of Briony's lies on the Tallis family. One is an unnerving account of the 1940 Allied retreat from Dunkirk, as seen from the point of view of Robbie, who won an early release from prison in return for joining the infantry. A second recounts Briony's stint as a nurse trainee during the darkest days of the London blitz. And the third revisits the Tallis family in the year 1999, the principle characters who survived the war having grown aged and frail themselves.

Though these sections of ''Atonement'' are each exquisitely worked entries that fit together intricately like handmade jigsaw-puzzle pieces, though the Dunkirk section in particular could stand alone as a bravura set-piece capturing the banality and horror of war, there is nothing self-conscious or mannered about Mr. McEwan's writing. Indeed ''Atonement'' emerges as the author's most deeply felt novel yet -- a novel that takes the glittering narrative pyrotechnics perfected in his last book, ''Amsterdam,'' and employs them in the service of a larger, tragic vision. It is novel that attests not only to Mr. McEwan's mastery of craft and virtuosic control of narrative suspense, but also to his knowledge of the human heart and its rage for symmetry and order.

The Books of The Times review on March 7, 2002, about ''Atonement,'' by Ian McEwan, misidentified the time period in the novel when the character Briony's stint as a nurse trainee in World War II is recounted. It is during the evacuation of Dunkirk, not the London blitz. A reader pointed out the error last week in an e-mail message.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at [email protected] . Learn more

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

100 Best Books of the 21st Century: As voted on by 503 novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers — with a little help from the staff of The New York Times Book Review.

Aleksei Navalny’s Prison Diaries: In the Russian opposition leader’s posthumous memoir, compiled with help from his widow, Yulia Navalnaya, Navalny faced the fact that Vladimir Putin might succeed in silencing him .

Jeff VanderMeer’s Strangest Novel Yet: In an interview with The Times , the author — known for his blockbuster Southern Reach series — talked about his eerie new installment, “Absolution.”

Discovering a New Bram Stoker Story: The work by the author of “Dracula,” previously unknown to scholars, was found by a fan who was trawling through the archives at the National Library of Ireland.

The Book Review Podcast: Each week, top authors and critics talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

A moment that destroys all joy in three lives

The daughter of an upper-class British family (Keira Knightley) falls for a housekeepers son (James McAvoy), with tragic results.

“Atonement” begins on joyous gossamer wings, and descends into an abyss of tragedy and loss. Its opening scenes in an English country house between the wars are like a dream of elegance, and then a 13-year-old girl sees something she misunderstands, tells a lie and destroys all possibility of happiness in three lives, including her own.

The movie’s opening act is like a breathless celebration of pure heedless joy, a demonstration of the theory that the pinnacle of human happiness was reached by life in an English country house between the wars. Of course that was more true of those upstairs than downstairs. We meet Cecilia Tallis ( Keira Knightley ), the bold, older daughter of an old family, and Robbie Turner ( James McAvoy ), their housekeeper’s promising son, who is an Oxford graduate, thanks to the generosity of Cecilia’s father. Despite their difference in social class, they are powerfully attracted to each other, and that leads to a charged erotic episode next to a fountain on the house lawn.

This meeting is seen from an upstairs window by Cecilia’s younger sister Briony ( Saoirse Ronan ), who thinks she sees Robbie mistreating her sister in his idea of rude sex play. We see the same scene later from Robbie and Cecilia’s point of view, and realize it involves their first expression of mutual love. But Briony does not understand, has a crush on Robbie herself, and as she reads an intercepted letter and interrupts a private tryst, her resentment grows until she tells the lie that will send Robbie out of Cecilia’s reach.

Oh, but the earlier scenes have floated effortlessly. Cecilia, as played by Knightley with stunning style, speaks rapidly in that upper-class accent that sounds like performance art. When I hear it, I despair that we Americans will ever approach such style with our words, which march out like baked potatoes. She is so beautiful, so graceful, so young, and Robbie may be working as a groundsman but is true blue, intelligent and in love with her. They deserve each other.

But that is not to be, as you know if you have read the Ian McEwan best seller that the movie is inspired so faithfully by. McEwan, one of the best novelists alive, allows the results of Briony’s vindictive behavior to grow offstage until we meet the principals again in the early days of the war. Robbie has enlisted and been posted to France. Cecilia is a nurse in London, and so is Briony, now 18, trying to atone for what she realizes was a tragic error. There is a meeting of the three, only once, in London, that demonstrates to them what they have all lost.

The film cuts back and forth between the war in France and the bombing of London, and there is a single (apparently) unbroken shot of the beach at Dunkirk that is one of the great takes in film history, achieved or augmented with CGI though it is. (If it looks real, in movie logic, it is real.) After an agonizing trek from behind enemy lines, Robbie is among the troops waiting to be evacuated, in a Dunkirk much more of a bloody mess than legend would have us believe. In the months before, the lovers have written, promising each other the happiness they have earned.

Each period and scene in the movie is compelling on its own terms, and then compelling on a deeper level as a playing out of the destiny that was sealed beside the fountain on that perfect summer’s day. It is only at the end of the film, when Briony, now an aged novelist played by Vanessa Redgrave , reveals facts about the story that we realize how thoroughly, how stupidly, she has continued for a lifetime to betray Cecilia, Robbie and herself.

The structure of the McEwan novel and this film directed by Joe Wright is relentless. How many films have we seen that fascinate in every moment and then, in the last moments, pose a question about all that has gone before, one that forces us to think deeply about what betrayal and atonement might really entail?

Wright, who also directed Knightley in his first film, “ Pride and Prejudice ,” (2005) shows a mastery of nuance and epic, sometimes in adjacent scenes. In the McEwan novel, he has a story that can hardly fail him and an ending that blindsides us with its implications. This is one of the year’s best films, a certain best picture nominee.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

- Brenda Blethyn as Grace Turner

- Vanessa Redgrave as Older Briony

- Keira Knightley as Cecilia Tallis

- James McAvoy as Robbie Turner

- Christopher Hampton

Based on the novel by

Directed by, leave a comment, now playing.

Woman of the Hour

Exhibiting Forgiveness

The Shadow Strays

Fanatical: The Catfishing of Tegan and Sara

Gracie & Pedro: Pets to the Rescue

Green Night

Latest articles

10 Underrated Horror Movies That Roger Ebert Loved (and Where to Watch Them)

I Doubled in Size: Lee Pace on the Legacy of “The Fall”

NYFF 2024: Little, Big, and Far, Lázaro at Night, 7 Walks with Mark Brown

We Were Lucky: Jon Landau and Stevie Van Zandt on “Road Diary: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band”

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

Review: Reality and fiction cross paths in powerfully dramatic 'Atonement'

Date October 21, 2024

Category In the News

Share Options

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Facebook

- Share to LinkedIn

Kyle MacMillan, Chicago Sun-Times

Review: 3.5 stars

Cathy Marston has crafted a fully-staged, emotionally charged production of Ian McEwan’s best-selling novel.

Story ballets traditionally drew on classic, centuries-old stories like “Don Quixote” or “Sleeping Beauty” and followed a well-established formula, with pantomime and formally structured grand pas de deux.

But contemporary choreographers are rethinking and reshaping this venerable dance form — few in more startling and potent fashion than Cathy Marston, a British choreographer who has served as director of Switzerland’s Ballett Zürich since 2023.

The Joffrey Ballet has presented four previous works by her, including “Of Mice and Men” in 2022, and Thursday evening it opened its 2024-25 season with the North American premiere of her powerful adaptation of Ian McEwan’s best-selling 2001 novel, “Atonement.”

As the title suggests, the work in very basic terms, is a story of atonement, though it is not clear that atonement is ever fully achieved. A 13-year-old girl living in 1935 on an estate in England witnesses a nighttime rape and literally points the finger at whom she believes did it.

She places the palms of her outstretched hands together in a dramatic, damning gesture that conjures a pointed gun, which metaphorically it is, swinging them through the air and directing them at the would-be perpetrator — one of the ballet’s most memorable movement motifs.

On a deeper level, “Atonement” asks: What is truth? What is fiction? What actually happened vs. what our memory and our built-in penchant for personal storytelling lead us to adamantly believe happened? And can we ever fully make up for past mistakes?

It is at once stark and sensual, shifting and surprising, with the biggest twist coming at the end when an epilogue makes clear that we have been experiencing a kind of ballet within a ballet or, perhaps more accurately, a ballet about a ballet.

If it all sounds a bit confounding, it can be, especially considering how easy it is to mix up some of the characters, and that’s why the unexpected yet essential epilogue helps so much, because it ties up many loose ends — but not all. Some of the answers are inevitably elusive.

That 13-year-old has become the ballet choreographer (an artist in the novel) she dreamed to be (the older and younger versions appear side by side), narrating this final section with a recorded voiceover and making clear that she shaped and manipulated this memory ballet within a ballet. Typically, dance shouldn’t need and shouldn’t have narration, but it works here.

There is much to praise about this affecting, deeply thought-provoking work, but it is possible to point to certain weaknesses, especially in the pacing. The opening act, which sets up all that is to follow, and some of the ensemble sections in the second act arguably run a bit long.

“Atonement” picks up momentum as it goes along, really getting its dramatic legs with the crime at the end of Act 1, building intensity with the raw, boldly etched expressionistic sections in Act 2 and forcefully culminating with the epilogue.

Marston is a master storyteller who uses a sharply delineated, often emphatic style of movement that is rooted in classical ballet but has a fresh, contemporary feel. Particularly striking, for example, is her exaggeratedly regimented and martial-like combinations for the soldiers in Act 2.

The cast is uniformly strong, starting with Yumi Kanazawa as Briony Tallis, convincingly conveying the youthful eagerness and naïve self-assuredness of the wannabe choreographer in Act 1 and her transformative maturity in Act 2.

But the real stars of this production are Alberto Velazquez and Amanda Assucena. The former portrays Robbie, the always-dreaming son of the housekeeper, Grace Turner (Anais Bueno). A wonderfully agile, fluid dancer, he twists and turns with his journal held above him at one point in a chair and kind of somersaults to the floor in one long, smooth motion.

As Briony’s older sister, Cecilia, Assucena has a kind of magnetic presence with a real sense of physical projection, with her expressive arms and athletic legs. As part of a youthful affair, seemingly more imagined than real, they dance a beautiful, sensual duet, including a spectacular lift in which she is splayed fully extended sideways on his back.

The sets by Michael Levine were simple and effective, a giant mural backdrop in Act 1 with just a couple of screens and few pieces of furniture, and, creating a kind of hermetic realm, a curtain that wraps across the back of the stage in Act 2 and is sometimes slid partially across the front at points in the action.

Composer Laura Rossi, who is best known for her work in movies and television, created an appropriately cinematic, mood-setting and richly orchestrated score for “Atonement” with expressive doses of harp, piano and mixed percussion. The Lyric Opera of Chicago Orchestra ably brought it to life under guest conductor Robert McConnell.

Read the full Chicago Sun-Times article here.

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

Why the End of Atonement Is a Triumph for Unreliable Narrators

Ian McEwan’s 2001 novel Atonement opens with a description of what it’s like to invent a world. Briony Tallis, 13 years old and enthralled by the power of storytelling (“you had only to write it down and you could have the world”) has written a little play for her family. She’s also “designed the posters, programs, and tickets, constructed the sales booth out of a folding screen tipped on its side, and lined the collection box in red crepe paper.” Every aspect of production of the seven-page drama, “written by her in a two-day tempest of composition,” fiercely belongs to her, and McEwan hovers over her labors like God dictating the Genesis story.

It’s easy to forget the beginning of a novel that became famous, in part, for its tablecloth-pulling ending. But Atonement has the power to send you scurrying back to its first pages once you finish, ready to play whack-a-mole with its wiggly circularity. It’s a book about misinterpretations that McEwan expects to be misinterpreted until its very last pages, when we find out that the entire book we’ve just read is the sixth draft of a novel by a much-older, quite successful Briony, making her both the unreliable narrator and the unreliable author. In between is a plot borne of Austen and Richardson that sweeps through the long 19th century of realist sagas, wiggles into Modernism, and ends on a postmodern questioning of the worth of the novel itself. It’s a feat of pastiche that transcends pastiche: It preserves the intoxication of narrative fiction while admitting that it’s farce.

Critics and book buyers agreed it was a masterpiece. Atonement became one of the first additions to the 21st-century canon after its publication in the U.K. twenty years ago, with a quarter million copies going into print in the U.S. alone before it won the National Books Critics Circle Award in 2003. (When he handed in the Atonement manuscript, McEwan told me, he informed his editor they’d be “lucky to sell 10,000 copies … because it’s really a book for other writers about reading and writing.” His editor told him it would sell in huge numbers “because it’s got the three elements that make it a must: a country house, the Second World War, a love affair.” It’s now sold over 2 million copies worldwide.) Academics wrote papers about it with hazy titles like “The Rhetoric of Intermediality” and “Briony’s Being-For” and it was made into a 2007 movie starring period-piece queen Keira Knightley and directed by Joe Wright, fresh off his debut Pride & Prejudic e remake. And readers still gush — and whine — on book forums and reading sites about that witchy ending.

Briony’s revelation at the end that she’s reshaped this story to her whims turns her into a kind of god, master of all narratives and shaper of fates. Which leaves us her pawns, delighted little fools pulled along on a con. Atonement is, as the title asserts, Briony’s apology to the people whose lives she’s used to populate her story. But it’s also her masterpiece, proof that her regrets won’t stop her from plundering one last time. Its ending reminds readers that fiction without misrepresentation is impossible.

Atonement ’s first three parts are told from multiple points of view — including that of Briony, the youngest of three siblings. The first and longest section is set in 1935 over the course of one roasting hot day and night at the Tallis family’s grand country home in the Surrey Hills. Precocious Briony has a “passion for tidiness” of all kinds; the darling of the family, her writing has been praised and encouraged to excess. Her older sister Cecelia, a restless recent graduate of the ladies’ college at Cambridge, is working through a newfound sex-tinged awkwardness with Robbie Turner, their charlady’s son and her childhood playmate. Like any good mother and father in a coming-of-age novel, the Tallis parents are a scant presence.

When Briony sees Cecelia and Robbie arguing by the fountain under her bedroom window, she imagines their quarrel — which is really over a broken heirloom vase — into her own (mis)understanding of how narrative works: Cecelia is the victim, Robbie the dastardly villain. That evening, she’ll misunderstand twice more. First, she sneakily opens a letter from Robbie to Cecelia that ends with the line “In my dreams I kiss your cunt, your sweet wet cunt.” She determines he’s a maniac, and later, when she walks in on them screwing in the family’s library, immediately assumes Robbie is raping her sister. Later, out searching the grounds for her visiting relatives, she makes out two figures in the tall grass, one “backing away from her and beginning to fade,” the other a frantic, disheveled Lola, her 15-year-old cousin. “In an instant, Briony understood completely,” McEwan writes. “She was nauseous with disgust and fear.” She isn’t sure, but tells Lola, “It was Robbie.” Lola never agrees with her, and the narrator hints that Briony is mistaken, but the police believe a child’s version of events, just as we eventually do. Robbie is wrongly branded a child rapist and hauled off.

The next two sections are set five years in the future, in 1940, as Europe steps into war. We first follow Robbie, released from prison to serve in the military, as he walks 25 miles toward the beach at Dunkirk, determined to return home to Cecelia despite the shrapnel lodged just below his heart. The next part returns to London, and to Briony, now 18, training as a war nurse and drafting “Two Figures by a Fountain,” a novella in impressions, based on the argument between Cecelia and Robbie that she saw from her bedroom window. Now wise to her own self-delusion and exhausted by guilt, she visits Cecelia to recant her accusation — and sees her sister reunited with Robbie, who insists that Briony do everything in her power to clear his name. Voilà, it’s the “atonement” readers expect.

Until now, a lovely, straightforward British wartime novel, full of wispy silk chiffon skirts and the buzz of the RAF — but then comes the coda. Leaping forward to 1999, we meet 77-year-old Briony as an established novelist, finishing up what will be her final manuscript: the novel we’ve just read, made of her memories, altered and reframed. She explains that Cecelia and Robbie really died in the Blitz and Dunkirk respectively. But “how could that constitute an ending?” Briony asks. “What sense of hope or satisfaction could a reader draw from such an account?” Distance, and six full drafts, have allowed her to riff.

This post-postmodern one-two punch knocked readers on their asses. While even the most formidable reviewers adored Atonement ’s genius, calling it “a tour de force” and “a beautiful and majestic fictional panorama,” what criticism they did have was reserved for its last pages. James Wood, then ascendant at the New Republic , considered it “McEwan’s finest and most complex novel” while declaring the twist ending “unnecessary” and decrying its “neatness.” The Sunday Telegraph declared it “frustrating,” and Anita Brookner questioned its wisdom. Hermione Lee in the Guardian called it a “quite familiar fictional trick.” The general public is still at war with itself over how they feel. Last fall, the Washington Post reported on a reader-generated list of literature’s all-time most disappointing endings: Atonement was ranked second, just after Romeo and Juliet. “I was touched,” McEwan told me during a recent phone conversation, to be “right next to Shakespeare.”

“Over the years I’ve encountered many people who will be absolutely infuriated [by the ending],” he said with a little laugh. “But I can’t help feeling very flattered by that. Those are just the people I wanted to address, because they were heavily invested in the story.”

So while the “trick” at the end is the big reveal, the more rewarding aspect is the knowledge that hints about Atonement ’s meticulous construction are hidden along the way. On a first reading, McEwan’s breadcrumb trail is barely visible, but on the second, it’s practically Day-Glo. Perhaps overconfident, (or more indebted to postmodernism herself than she lets on) Briony repeatedly drops hints that she was even manufacturing this story as a child, and that it is shifting and changing even as she writes it from the perch of old age. Just after she witnesses the fountain scene, Briony writes, she knew “that whatever actually happened drew its significance from her published work and would not have been remembered without it.”

In the third section, as an 18-year-old writer, Briony receives a helpful rejection letter from real-life (as in, actually real-life) magazine editor Cyril Connolly. He praises “Two Figures by a Fountain,” as “arresting,” though her style “owed a little too much to the techniques of Mrs. Woolf.” He reminds her to think of her readers: “They retain a childlike desire to be told a story, to be held in suspense, to know what happens.” Those last two phrases are diametrical, of course, which encapsulates the experiment of Atonement itself.

The ending isn’t a feather in the novel’s cap, tacked on unnecessarily as some critics lamented. It’s the novel’s reason for being. The little girl whose play once crumbled into a mire of familial infighting pulls off an incredible caper: She’s both offered a lengthy apology and finally written the ravishing novel that she once imagined, just minutes after watching that argument between Cecelia and Robbie by the fountain: “She sensed she could write a scene like the one by the fountain and she could include a hidden observer like herself. She could imagine herself hurrying down now to her bedroom, to a clean block of lined paper and her marbled, Bakelite pen.” As for Robbie and Cecelia — still loved by her, still dead — she pats herself on the back for reviving them in her fiction, which she calls “a final act of kindness … I gave them happiness, but I was not so self-serving as to let them forgive me.”

Briony knows that her novel won’t be published until after her death or incapacitation; she won’t experience censure or scandal. Perhaps the most subversive thing about Atonement is that its narrator isn’t hobbled by the weight of her guilt. Instead, she’s victorious: “She was under no obligation to the truth, she had promised no one a chronicle.”

I asked McEwan if some bit of Briony is triumphant. “I would take the Jamesian view,” he demurred, “that she’s lived the examined life.”

One that’s been examined — and fiddled with — until it’s no longer a life. It’s a novel.

More From This Series

- No, They Weren’t Dead the Whole Time

- Harrison Ford Didn’t Do It

- What Makes Viewers ‘Tune In Next Week"?

- the art of ending things

- twist endings

Most Viewed Stories

- Cinematrix No. 211: October 23, 2024

- Trust the Kieran Culkin Process

- Everything That’s Happened to the Menendez Brothers Since Monsters

- ‘Blindsided’ Brianna Chickenfry Confirms Zach Bryan Breakup

- Taylor Swift Forges Heterosexual Alliance With Dave Portnoy

- Romeo and Juliet Was a Tragedy

- Only Murders in the Building Recap: On Fire

Most Popular

What is your email.

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

- About Rotten Tomatoes®

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening This Week

- Top Box Office

- Coming Soon to Theaters

- Certified Fresh Movies

Movies at Home

- Fandango at Home

- Prime Video

- Most Popular Streaming Movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- 86% Smile 2 Link to Smile 2

- 99% Anora Link to Anora

- 79% We Live in Time Link to We Live in Time

New TV Tonight

- 86% What We Do in the Shadows: Season 6

- 80% Poppa's House: Season 1

- -- Territory: Season 1

- -- Before: Season 1

- -- Hellbound: Season 2

- -- The Equalizer: Season 5

- -- Breath of Fire: Season 1

- -- Beauty in Black: Season 1

- -- Like a Dragon: Yakuza: Season 1

Most Popular TV on RT

- 94% The Penguin: Season 1

- 82% Agatha All Along: Season 1

- 78% Disclaimer: Season 1

- 91% Rivals: Season 1

- 78% Hysteria!: Season 1

- 100% The Lincoln Lawyer: Season 3

- 79% Teacup: Season 1

- 100% From: Season 3

- 85% Sweetpea: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

Certified fresh pick

- 96% Shrinking: Season 2 Link to Shrinking: Season 2

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

Best TV Shows of 2024: Best New Series to Watch Now

50 Best New Horror Movies of 2024

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

The Most Anticipated Movies of 2025

One Last Visit to What We Do In The Shadows

- Trending on RT

- Verified Hot Movies

- TV Premiere Dates

- Gladiator II First Reactions

- Halloween Programming Guide

Atonement Reviews

…Atonement might look from its glamorous shell like the usual British fantasy about WWII romance, but has something tougher, more meta and more timeless inside…

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Sep 7, 2024

Atonement transcends the expectations of its country-house setting, via the privations of war, to deliver a knockout twist that works better on the screen than it did on the page.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | May 30, 2024

Your heart breaks for Cecilia, Robbie, and what should have been, as well as an adult Briony...

Full Review | Oct 23, 2023

Director Joe Wright... drinks in the period while reaching beyond the surface and into the unsettled emotional lives of the characters—passion, betrayal, guilt.

Full Review | Jun 11, 2023

We got a run of, again, very very pretty images that, for me, added up to a lot of pretty images that never got around to affecting me on an emotional level

Full Review | Jul 2, 2021

This level of storytelling and artistry is a rare treat, demonstrating director Joe Wright's knack for working with adapted material.

Full Review | Original Score: 9/10 | Nov 24, 2020

Joe Wright (director) and Christopher Hampton (writer) have not only built an exciting epic from the book, but also provide the visual discovery of an ending that was already outstanding in the novel, but... reaches new heights. [Full review in Spanish]

Full Review | Original Score: 3/5 | Oct 14, 2020

McAvoy, long an underrated actor and also a Golden Globe nominee, fares even better here as the wrongly accused Robbie.

Full Review | Original Score: 3.5/4.0 | Sep 2, 2020

Where Wright does succeed is in making absolutely lucid McEwan's fascinating central theme of atonement.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Oct 29, 2019

Every bit as emotionally affecting as it is visually sweeping.

Full Review | Original Score: 3.5/4 | Jul 6, 2019

It is an elegant and sophisticated film, one that never condescends or shirks from the complexity of the novel and its grand themes - war, love, sex, memory, betrayal, redemption - but it's also strangely unfeeling.

Full Review | Aug 23, 2018

Keep any advance knowledge of this superb drama to an absolute minimum, as it deserves every chance to work its devastating wonders upon an unsuspecting audience.

Full Review | Original Score: 4.5/5 | Aug 8, 2018

Impeccable design, perfect casting, sound that takes the clack of a typewriter and embeds it into all sorts of furious onscreen rhythms... I was swooning even before the love story kicked in.

Full Review | Aug 22, 2017

Full Review | Original Score: A- | Feb 14, 2012

Atonement's goal is so ephemeral that film may not be able to do it complete justice. All that said, it's still a fantastic piece of craftsmanship, benefiting from loving direction and excellent performances.

Full Review | Original Score: 8/10 | Dec 28, 2010

An epic, grandiose, and immensely sad film, Atonement is an extremely well crafted, visually rich love story set during a tumultuous time of war, where two impassioned characters are forever torn apart by the selfish jealousy of another.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Jul 7, 2010

Figurines in a teacup set, shipped over in boxes labeled 'For your consideration'

Full Review | Aug 27, 2009

Frustratingly uneven, struggling to maintain momentum as it lurches through extended lulls and indulges in cliched genre affectations.

Full Review | Original Score: 2.5/4 | Jul 27, 2009

zaslu%u017Euje pohvale, ali ne onakve kakve bi trebao imati ozbiljni kandidat za "Oscara"

Full Review | Original Score: 7/10 | Jul 15, 2009

Players outshine the script

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Jun 28, 2009

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Flesh on Flesh

Ian McEwan, whose novels have tended to be short, smart, and saturnine, has produced a beautiful and majestic fictional panorama, “Atonement” (Doubleday; $26). The novel’s first half takes place over two summer days in 1935, on a Surrey estate occupied by the Tallis family: Jack, the head of the household, whose work for the Ministry of Defense keeps him night after night in London; Emily, his wife, who is prone to migraines and long spells of daydreaming in her bed; Leon, the eldest child and only son, twenty-five and working in London in a modest position at a bank, though he has a law degree; his sister Cecilia, younger by two years, fresh from her finals at Cambridge, bored and at loose ends; and our heroine, thirteen-year-old Briony, given to posing philosophical questions and perusing the thesaurus, and for the past two years an increasingly active writer. She has just composed a play, “The Trials of Arabella,” to be performed in honor of her brother’s homecoming. He is bringing a wealthy friend, Paul Marshall, and there are three cousins just arrived from the north, the Quinceys—Lola, fifteen, and nine-year-old twins, Jackson and Pierrot—who are to act in Briony’s play. The three are refugees from a broken household: Aunt Hermione, Emily Tallis’s younger sister, has run off to Paris with “a man who worked in the wireless.” To this cast of characters add some servants and the anomalous figure of Robbie Turner. Robbie is the son of the Tallises’ former gardener; when the boy’s father deserted him and his mother, they were charitably taken up by Jack Tallis, who gave Grace Turner the gardener’s bungalow and has paid for Robbie’s education, including three years at Cambridge. He has just passed his finals with a first in literature, while Cecilia earned only a third. Though at Cambridge simultaneously, they rarely met there, and are tense and awkward with each other this summer, in the domain where they grew up together. They, it is perhaps not too much to reveal, supply the novel’s love interest.

McEwan’s epigraph is from Jane Austen, and promises a spacious family novel of humorous interplay, romantic intrigues, and near-tragic misunderstandings. The promise is to some extent kept; the homesick twins and the blossoming, manipulative Lola inject disturbance into the stagnant Tallis household. But in the warmth of these days, the year’s hottest, a Virginia Woolfian shimmer overlays the Austenish plot, which keeps threatening to dissolve. The play, for example, does not go on (until sixty-four years later). Jack Tallis, the powerful absentee Old Man, an offstage deus ex machina, never descends. Instead, amid many images of water and vegetation and architectural nicety, various viewpoints backtrack and overlap, and certain scenes are replayed from widely different perspectives. The writing is conspicuously good; and this goodness turns out to be, eventually, a subject of criticism—by Cyril Connolly, no less—in a droll show of artistic self-reference, although in the meantime it works an authentic spell. Picture after picture, in the haze of this midsummer, arises to challenge and flatter the reader’s capacity for visualization. At a key moment, a precious vase is tussled over, and a fragment breaks off and falls into a fountain:

With a sound like a dry twig snapping, a section of the lip of the vase came away in his hand, and split into two triangular pieces which dropped into the water and tumbled to the bottom in a synchronous, see-sawing motion, and lay there, several inches apart, writhing in the broken light.

That seesawing synchronicity, that writhing in the broken light show us more than we had expected to see. A seemingly half-baked comparison to savanna writhes on, renews itself, and ends with a smiling metaphoric flourish:

Then, nearer, the estate’s open parkland, which today had a dry and savage look, roasting like a savanna, where isolated trees threw harsh stumpy shadows and the long grass was already stalked by the leonine yellow of high summer.

The reader, seeing through Cecilia’s languid eyes, is brought up short by virtually abstract images:

She lolled against the warm stone, lazily finishing her cigarette and contemplating the scene before her—the foreshortened slab of chlorinated water, the black inner tube of a tractor tyre propped against a deck chair, the two men in cream linen suits of infinitesimally different hues, bluish-gray smoke rising against the bamboo green.

“Infinitesimally different hues” is the mode, as skyscapes, physiognomies, gestures ("She turned aside and made a steeple of her hands to enclose her nose and mouth and pressed her fingers into the corners of her eyes"), and scents ("the grasses giving off their sweet cattle smell, the hard-fired earth which still held the embers of the day’s heat and exhaled the mineral odor of clay, and the faint breeze carrying from the lake a flavor of green and silver") are evoked with a delicious care and verbal cunning. This is written , each page subliminally announces, and that undercurrent prepares the reader for the atonement of the title: Briony, the writer and the character becoming one, atones for a childish blunder with a mature woman’s fiat of creation. Even at the age of thirteen she exults to herself, “There was nothing she could not describe.”

The novel’s second section transports us to another prose climate, as the terrors and confusions of the British retreat to Dunkirk in 1940 are harrowingly detailed. Some of the details are surprising and piquant—a caged parrot caught up in the chaotic scramble, a peasant with his collie plowing a field in intervals between bombing and strafing attacks, soldiers shooting their horses in the head and their motorized vehicles in the radiator. In the desperately crowded and underprovisioned conditions around Dunkirk, British soldiers threaten and assault one another while the enemy swoops overhead and the R.A.F. and the Royal Navy fail to materialize. As a whole, the section is gripping, but it is not extraordinary, quite, like the novel’s first half. The element of the marvellous—the latently menacing seethe of the everyday—has been replaced by the more vulgar excitement of overt peril. If we marvel, it is at the ability of contemporary English writers (McEwan was born in 1948) to capture the tastes and sights of a past they did not witness even as children. It is as if the earlier generation of writers—Waugh, Greene, Green, Golding, Powell, Orwell, Bowen, Spark, and dozens of lessers—had laid down, on this dense island soil, an accessible past, while Americans must reinvent their more scattered country from scratch. The imaginary writer of “Atonement” in her last pages expresses her debt to the research facilities at the Imperial War Museum, in Lambeth, and to an “old colonel” who has testily corrected her terminology and fine points. Her sixty pages of war’s turmoil are followed by sixty of war’s bitter fruits, in the form of the atrocious casualties that Briony, who has signed up as a probationer nurse, witnesses and learns to minister to. She extracts shrapnel, talks French to a young man who dies in her arms, removes the bandages from a blasted face:

Using a pair of surgical tongs, she began carefully pulling away the sodden, congealed lengths of ribbon gauze from the cavity in the side of his face. When the last was out, the resemblance to the cutaway model they used in anatomy classes was only faint. This was all ruin, crimson and raw. She could see through his missing cheek to his upper and lower molars, and the tongue glistening, and hideously long.

The reader will possibly recall how the novel’s lovers, in their moment of mutual possession, find their way to unself-conscious passion through “the contact of tongues, alive and slippery muscle, moist flesh on flesh.” Lust and disgust keep close company; in McEwan’s hypnotic first novel, “The Cement Garden” (1978), another set of children left to their own devices, in another summer of unusual heat, experience the debility and putrescence of the body as well as its tabooed allure. “Atonement” concerns, among other historical phenomena, puritanism in 1935, when an impulsive four-letter word in a man’s love letter could draw the attention of the authorities. The frail, moist flesh, mutilated in war, corseted and shamed in peacetime, and subject, in the long view, to swift decay, gives this intricately composed narrative its mournful, surging life. The poems of Auden and Housman are talismanic volumes within its furniture, and “Clarissa” with its scribbling heroine, but equally prominent is Gray’s “Anatomy.”

The novel’s bloody illustrations of the horrors of war compel assent and pity, and yet, such is the novel reader’s romantic nature, it is the lovers that keep us turning the page; theirs is the consummation we devoutly wish. Our wish is granted, but with a duplicitous art. “Atonement,” in its tenderness and doubleness and final effect of height, in its postmodern concern with its own writing, and in its central topic of two upper-class sisters in the period between the world wars, has a striking happenstance resemblance to Margaret Atwood’s “The Blind Assassin.” Both revert, from the perspective of an old woman facing death near the bloated end of the twentieth century, to an era when a certain grandeur could attach to human decisions, made as they were under the shadow of global war and in living memory of the faded virtues—loyalty and honesty and valor—that sought to soften what McEwan calls the “iron principle of self-love.” People could still dedicate a life, gamble it on one throw. Compared with today’s easy knowingness and self-protective irony, feelings then had a hearty naïveté, a force developed amid repression and scarcity and linked to a sense of transcendent adventure; novels need this force, and must find it where they can, if only in the annals of the past. ♦

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Directed by Joe Wright. Drama, Mystery, Romance, War. R. 2h 3m. By A.O. Scott. Dec. 7, 2007. Joe Wright’s “Atonement” begins in the endlessly photogenic, thematically pregnant interwar period.

In a moment of innocence, jealousy and willfulness she betrays Robbie, falsely accusing him of a crime, for which he is imprisoned, and her way of making amends is to reimagine the history of ...

ATONEMENT. By Ian McEwan. 351 pages. Nan A. Talese/ Doubleday. $26. Ian McEwan's remarkable new novel ''Atonement'' is a love story, a war story and a story about the destructive powers of the...

4 min read. The daughter of an upper-class British family (Keira Knightley) falls for a housekeeper s son (James McAvoy), with tragic results. “Atonement” begins on joyous gossamer wings, and descends into an abyss of tragedy and loss.

Kyle MacMillan, Chicago Sun-Times Review: 3.5 stars Cathy Marston has crafted a fully-staged, emotionally charged production of Ian McEwan’s best-selling novel. Story ballets traditionally drew on classic, centuries-old stories like “Don Quixote” or “Sleeping Beauty” and followed a well-established formula, with pantomime and formally structured grand pas de deux.

Box office. $131 million [2] Atonement is a 2007 romantic war drama film directed by Joe Wright and starring James McAvoy, Keira Knightley, Saoirse Ronan, Romola Garai, and Vanessa Redgrave. It is based on the 2001 novel by Ian McEwan. The film chronicles a crime and its consequences over six decades, beginning in the 1930s.

This sweeping English drama, based on the book by Ian McEwan, follows the lives of young lovers Cecilia Tallis (Keira Knightley) and Robbie Turner (James McAvoy).

Atonement is, as the title asserts, Briony’s apology to the people whose lives she’s used to populate her story. But it’s also her masterpiece, proof that her regrets won’t stop her from...

An epic, grandiose, and immensely sad film, Atonement is an extremely well crafted, visually rich love story set during a tumultuous time of war, where two impassioned characters are forever...

Ian McEwan, whose novels have tended to be short, smart, and saturnine, has produced a beautiful and majestic fictional panorama, “Atonement” (Doubleday; $26).