Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

For centuries, people have tried to understand the behaviors and beliefs associated with falling in love. What explains the wide range of emotions people experience? How have notions of romance evolved over time? As digital media becomes a permanent fixture in people’s lives, how have these technologies changed how people meet?

Examining some of these questions are Stanford scholars.

From the historians who traced today’s ideas of romance to ancient Greek philosophy and Arab lyric poetry, to the social scientists who have examined the consequences of finding love through an algorithm, to the scientists who study the love hormone oxytocin, here is what their research reveals about matters of the heart.

The evolution of romance

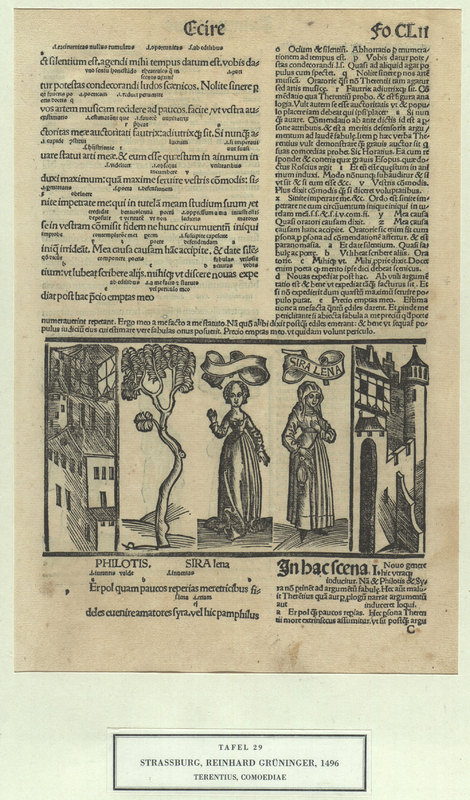

How romantic love is understood today has several historical origins, says Robert Pogue Harrison , the Rosina Pierotti Professor in Italian Literature and a scholar of romance studies.

For example, the idea of finding one’s other half dates back to ancient Greek mythology, Harrison said. According to Aristophanes in Plato’s Symposium , humans were once complete, “sphere-like creatures” until the Greek gods cut them in half. Ever since, individuals have sought after their other half.

Here are some of those origin stories, as well as other historical perspectives on love and romance, including what courtship looked like in medieval Germany and in Victorian England, where humor and innuendo broke through the politics of the times.

Stanford scholar examines origins of romance

Professor of Italian literature Robert Pogue Harrison talks about the foundations of romantic love and chivalry in Western civilization.

Medieval songs reflect humor in amorous courtships

Through a new translation of medieval songs, Stanford German studies Professor Kathryn Starkey reveals an unconventional take on romance.

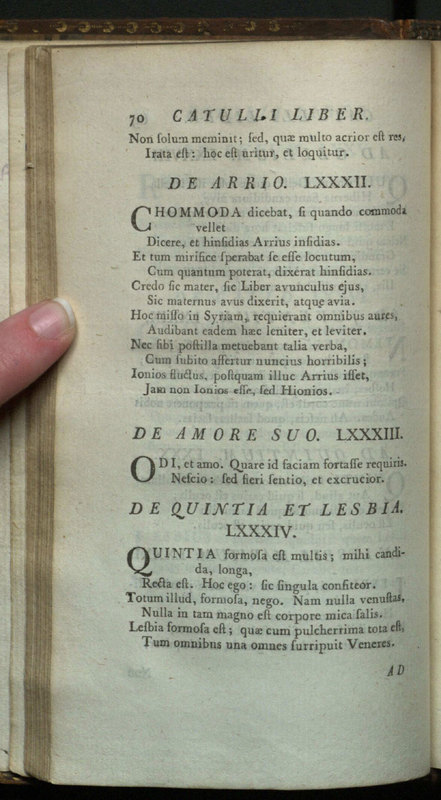

The aesthetics of sexuality in Victorian novels

In Queen Victoria’s England, novelists lodged erotic innuendo in descriptive passages for characters to express sexual desire.

Getting to the ‘heart’ of the matter

Stanford Professor Haiyan Lee chronicles the Chinese “love revolution” through a study of cultural changes influenced by Western ideals.

Love in the digital age

Where do people find love today? According to recent research by sociologist Michael Rosenfeld , meeting online is now the most popular way to meet a partner.

“The rise of the smartphone took internet dating off the desktop and put it in everyone’s pocket, all the time,” said Rosenfeld. He found that 39 percent of heterosexual couples met their significant other online, compared to 22 percent in 2009.

As people increasingly find connections online, their digital interactions can provide insight into people’s preferences in a partner.

For example, Neil Malhotra , the Edith M. Cornell Professor of Political Economy, analyzed thousands of interactions from an online dating website and found that people seek partners from their own political party and with similar political interests and ideologies. Here is some of that research.

Online dating is the most popular way couples meet

Matchmaking is now done primarily by algorithms, according to new research from Stanford sociologist Michael Rosenfeld. His new study shows that most heterosexual couples today meet online.

Cupid’s code: Tweaking an algorithm can alter the course of finding love online

A few strategic changes to dating apps could lead to more and better matches, finds Stanford GSB’s Daniela Saban.

Political polarization even extends to romance

New research reveals that political affiliation rivals education level as one of the most important factors in identifying a potential mate.

Turns out that opposites don’t attract after all

A study of “digital footprints” suggests that you’re probably drawn to personalities a lot like yours.

Stanford scholars examine the lies people tell on mobile dating apps

Lies to appear more interesting and dateable are the most common deception among mobile dating app users, a new Stanford study finds.

The science of love

It turns out there might be some scientific proof to the claim that love is blind. According to one Stanford study , love can mask feelings of pain in a similar way to painkillers. Research by scientist Sean Mackey found intense love stimulates the same area of the brain that drugs target to reduce pain.

“When people are in this passionate, all-consuming phase of love, there are significant alterations in their mood that are impacting their experience of pain,” said Mackey , chief of the Division of Pain Medicine. “We’re beginning to tease apart some of these reward systems in the brain and how they influence pain. These are very deep, old systems in our brain that involve dopamine – a primary neurotransmitter that influences mood, reward and motivation.”

While love can dull some experiences, it can also heighten other feelings such as sociability. Another Stanford study found that oxytocin, also known as the love hormone because of its association with nurturing behavior, can also make people more sociable. Here is some of that research.

Looking for love in all the wrong hormones

A study involving prairie vole families challenges previous assumptions about the role of oxytocin in prosocial behavior.

Give your sweetheart mushrooms this Valentine’s Day, says Stanford scientist

A romantic evening of chocolate and wine would not be possible without an assist from fungi, says Stanford biology professor Kabir Peay. In fact, truffles might be the ultimate romantic gift, as they exude pheromones that can attract female mammals.

Love takes up where pain leaves off, brain study shows

Love-induced pain relief was associated with the activation of primitive brain structures that control rewarding experiences.

Come together: How social support aids physical health

A growing body of research suggests that healthy relationships with spouses, peers and friends are vital for not just mental but also physical health.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Cutting through the fog of long COVID

Warning for younger women: Be vigilant on breast cancer risk

Study shows vitamin D doesn’t cut cardiac risk

When love and science double date.

Illustration by Sophie Blackall

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Sure, your heart thumps, but let’s look at what’s happening physically and psychologically

“They gave each other a smile with a future in it.” — Ring Lardner

Love’s warm squishiness seems a thing far removed from the cold, hard reality of science. Yet the two do meet, whether in lab tests for surging hormones or in austere chambers where MRI scanners noisily thunk and peer into brains that ignite at glimpses of their soulmates.

When it comes to thinking deeply about love, poets, philosophers, and even high school boys gazing dreamily at girls two rows over have a significant head start on science. But the field is gamely racing to catch up.

One database of scientific publications turns up more than 6,600 pages of results in a search for the word “love.” The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is conducting 18 clinical trials on it (though, like love itself, NIH’s “love” can have layered meanings, including as an acronym for a study of Crohn’s disease). Though not normally considered an intestinal ailment, love is often described as an illness, and the smitten as lovesick. Comedian George Burns once described love as something like a backache: “It doesn’t show up on X-rays, but you know it’s there.”

Richard Schwartz , associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and a consultant to McLean and Massachusetts General (MGH) hospitals, says it’s never been proven that love makes you physically sick, though it does raise levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that has been shown to suppress immune function.

Love also turns on the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is known to stimulate the brain’s pleasure centers. Couple that with a drop in levels of serotonin — which adds a dash of obsession — and you have the crazy, pleasing, stupefied, urgent love of infatuation.

It’s also true, Schwartz said, that like the moon — a trigger of its own legendary form of madness — love has its phases.

“It’s fairly complex, and we only know a little about it,” Schwartz said. “There are different phases and moods of love. The early phase of love is quite different” from later phases.

During the first love-year, serotonin levels gradually return to normal, and the “stupid” and “obsessive” aspects of the condition moderate. That period is followed by increases in the hormone oxytocin, a neurotransmitter associated with a calmer, more mature form of love. The oxytocin helps cement bonds, raise immune function, and begin to confer the health benefits found in married couples, who tend to live longer, have fewer strokes and heart attacks, be less depressed, and have higher survival rates from major surgery and cancer.

Schwartz has built a career around studying the love, hate, indifference, and other emotions that mark our complex relationships. And, though science is learning more in the lab than ever before, he said he still has learned far more counseling couples. His wife and sometime collaborator, Jacqueline Olds , also an associate professor of psychiatry at HMS and a consultant to McLean and MGH, agrees.

Spouses Richard Schwartz and Jacqueline Olds, both associate professors of psychiatry, have collaborated on a book about marriage.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

More knowledge, but struggling to understand

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago, but I don’t think it tells us very much that we didn’t already know about love,” Schwartz said. “It’s kind of interesting, it’s kind of fun [to study]. But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.”

Love and companionship have made indelible marks on Schwartz and Olds. Though they have separate careers, they’re separate together, working from discrete offices across the hall from each other in their stately Cambridge home. Each has a professional practice and independently trains psychiatry students, but they’ve also collaborated on two books about loneliness and one on marriage. Their own union has lasted 39 years, and they raised two children.

“I think we know a lot more scientifically about love and the brain than we did a couple of decades ago … But do we think that makes us better at love, or helping people with love? Probably not much.” Richard Schwartz, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

“I have learned much more from doing couples therapy, and being in a couple’s relationship” than from science, Olds said. “But every now and again, something like the fMRI or chemical studies can help you make the point better. If you say to somebody, ‘I think you’re doing this, and it’s terrible for a relationship,’ they may not pay attention. If you say, ‘It’s corrosive, and it’s causing your cortisol to go way up,’ then they really sit up and listen.”

A side benefit is that examining other couples’ trials and tribulations has helped their own relationship over the inevitable rocky bumps, Olds said.

“To some extent, being a psychiatrist allows you a privileged window into other people’s triumphs and mistakes,” Olds said. “And because you get to learn from them as they learn from you, when you work with somebody 10 years older than you, you learn what mistakes 10 years down the line might be.”

People have written for centuries about love shifting from passionate to companionate, something Schwartz called “both a good and a sad thing.” Different couples experience that shift differently. While the passion fades for some, others keep its flames burning, while still others are able to rekindle the fires.

“You have a tidal-like motion of closeness and drifting apart, closeness and drifting apart,” Olds said. “And you have to have one person have a ‘distance alarm’ to notice the drifting apart so there can be a reconnection … One could say that in the couples who are most successful at keeping their relationship alive over the years, there’s an element of companionate love and an element of passionate love. And those each get reawakened in that drifting back and forth, the ebb and flow of lasting relationships.”

Children as the biggest stressor

Children remain the biggest stressor on relationships, Olds said, adding that it seems a particular problem these days. Young parents feel pressure to raise kids perfectly, even at the risk of their own relationships. Kids are a constant presence for parents. The days when child care consisted of the instruction “Go play outside” while mom and dad reconnected over cocktails are largely gone.

When not hovering over children, America’s workaholic culture, coupled with technology’s 24/7 intrusiveness, can make it hard for partners to pay attention to each other in the evenings and even on weekends. It is a problem that Olds sees even in environments that ought to know better, such as psychiatry residency programs.

“There are all these sweet young doctors who are trying to have families while they’re in residency,” Olds said. “And the residencies work them so hard there’s barely time for their relationship or having children or taking care of children. So, we’re always trying to balance the fact that, in psychiatry, we stand for psychological good health, but [in] the residency we run, sometimes we don’t practice everything we preach.”

“There is too much pressure … on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. … Of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.” Jacqueline Olds, associate professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

All this busy-ness has affected non-romantic relationships too, which has a ripple effect on the romantic ones, Olds said. A respected national social survey has shown that in recent years people have gone from having three close friends to two, with one of those their romantic partner.

More like this

Strength in love, hope in science

Love in the crosshairs

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

“Often when you scratch the surface … the second [friend] lives 3,000 miles away, and you can’t talk to them on the phone because they’re on a different time schedule,” Olds said. “There is too much pressure, from my point of view, on what a romantic partner should be. They should be your best friend, they should be your lover, they should be your closest relative, they should be your work partner, they should be the co-parent, your athletic partner. There’s just so much pressure on the role of spouse that of course everybody isn’t able to quite live up to it.”

Since the rising challenges of modern life aren’t going to change soon, Schwartz and Olds said couples should try to adopt ways to fortify their relationships for life’s long haul. For instance, couples benefit from shared goals and activities, which will help pull them along a shared life path, Schwartz said.

“You’re not going to get to 40 years by gazing into each other’s eyes,” Schwartz said. “I think the fact that we’ve worked on things together has woven us together more, in good ways.”

Maintain curiosity about your partner

Also important is retaining a genuine sense of curiosity about your partner, fostered both by time apart to have separate experiences, and by time together, just as a couple, to share those experiences. Schwartz cited a study by Robert Waldinger, clinical professor of psychiatry at MGH and HMS, in which couples watched videos of themselves arguing. Afterwards, each person was asked what the partner was thinking. The longer they had been together, the worse they actually were at guessing, in part because they thought they already knew.

“What keeps love alive is being able to recognize that you don’t really know your partner perfectly and still being curious and still be exploring,” Schwartz said. “Which means, in addition to being sure you have enough time and involvement with each other — that that time isn’t stolen — making sure you have enough separateness that you can be an object of curiosity for the other person.”

Share this article

You might like.

Researchers say new AI tool sharpens diagnostic process, may help identify more people needing care

Pathologist explains the latest report from the American Cancer Society

Outdoor physical activity may be a better target for preventive intervention, says researcher

U.S. fertility rates are tumbling, but some families still go big. Why?

It’s partly matter of faith. Economist examines choice to have large families in new book.

Are optimists the realists?

Humanity is doing better than ever yet it often doesn’t seem that way. In podcast, experts make the case for fact-based hope.

Seem like peanut allergies were once rare and now everyone has them?

Surgeon, professor Marty Makary examines damage wrought when medicine closes ranks around inaccurate dogma

- CONTACT A LOCATION

- REQUEST APPOINTMENT

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- View Locations

© 2014 Riordan Clinic All Rights Reserved

- High Dose IV Vitamin C (IVC)

- Integrative Medicine

- Integrative Oncology

The Research on Love: A Psychological, Scientific Perspective on Love

Dr. Nina Mikirova

And now here is this topic about love, the subject without which no movie, novel, poem or song can exist. This topic has fascinated scientists, philosophers, historians, poets, playwrights, novelists, and songwriters. I decided to look at this subject from a scientific point of view. It was very interesting to research and to write this article, and I am hoping it will be interesting to you as a reader.

Whereas psychological science was slow to develop active interest in love, the past few decades have seen considerable growth in research on the subject. The following is a comprehensive review of the central and well-established findings from psychologically-informed research on love and its influence in adult human relationships as presented in the article: “Love. What Is It, Why Does It Matter, and How Does It Operate?” by H. Reis and A. Aron. A brief summary of the ideas from this article is presented below.

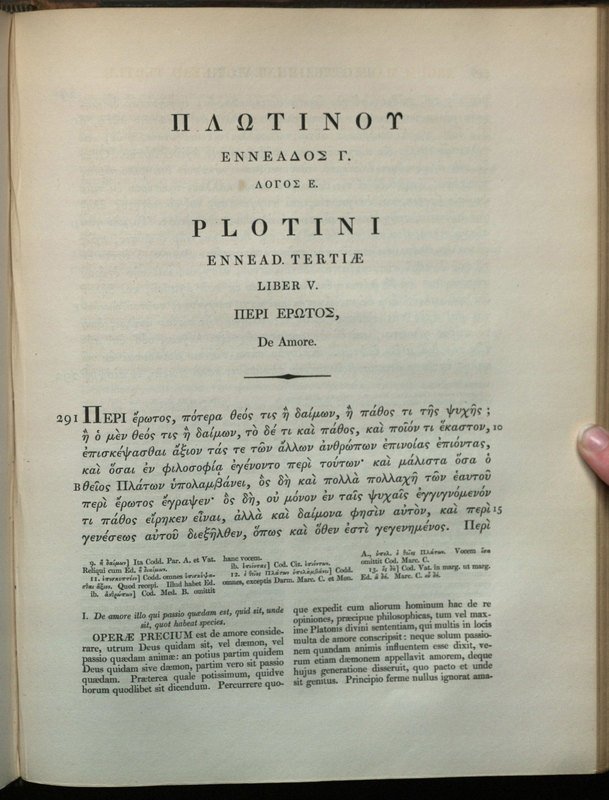

A BRIEF HISTORY OF LOVE RESEARCH

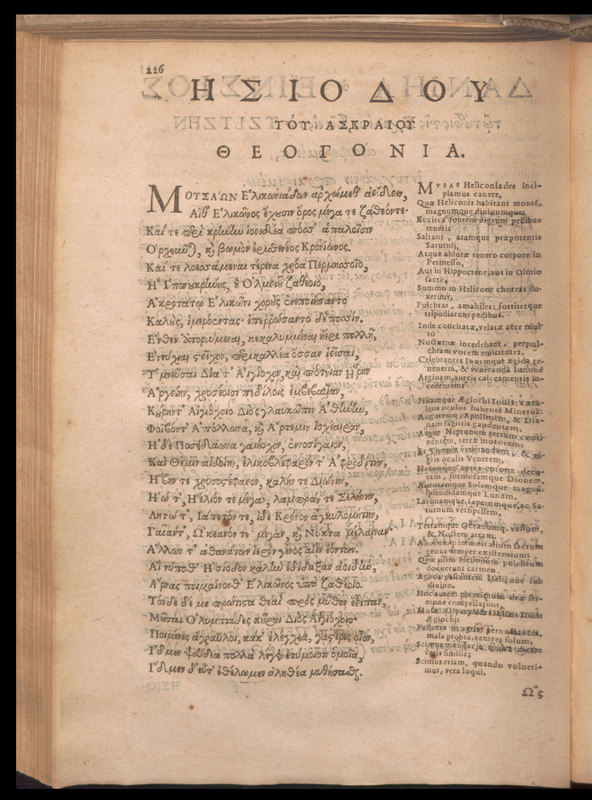

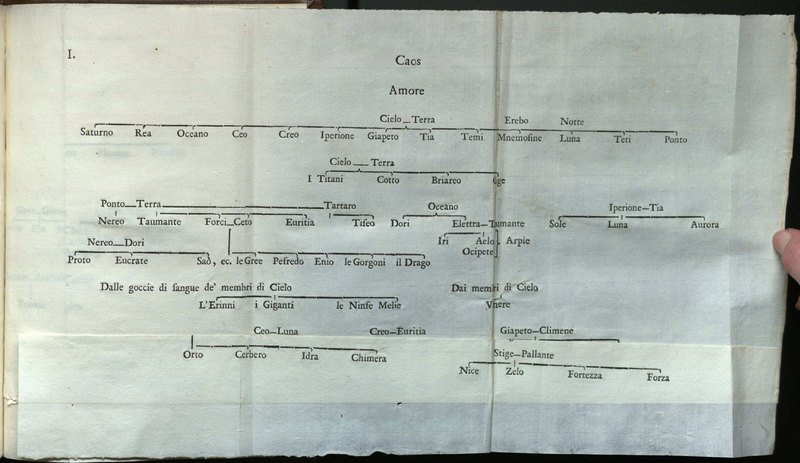

Most popular contemporary ideas about love can be traced to the classical Greek philosophers. Prominent in this regard is Plato’s Symposium. It is a systematic and seminal analysis whose major ideas

have probably influenced contemporary work on love more than all subsequent philosophical work combined. However, four major intellectual developments of the 19th and 20th centuries provided key insights that helped shape the agenda for current research and theory of love.

The first of these was led by Charles Darwin, who proposed that reproductive success was the central process underlying the evolution of species. Evolutionary theorizing has led directly to such currently popular concepts as mate preference, sexual mating strategies, and attachment, as well as to the adoption of a comparative approach across species.

A second important figure was Sigmund Freud. He introduced many psychodynamic principles, such as the importance of early childhood experiences, the powerful impact of motives operating outside of awareness, the role of defenses in shaping the behavioral expression of motives, and the role of sexuality as a force in human behavior.

A third historically significant figure was Margaret Mead. Mead expanded awareness with vivid descriptions of cultural variations in the expression of love and sexuality. This led researchers to consider the influence of socialization and to recognize cultural variation in many aspects of love.

The emerging women’s movement during the 1970s also contributed to a cultural climate that made the study of what had been traditionally thought of as ‘‘women’s concerns’’ not only acceptable, but in fact necessary for the science of human behavior. At the same time, a group of social psychologists were beginning their work to show that adult love could be studied experimentally and in the laboratory.

WHAT’S PSYCHOLOGY GOT TO DO WITH LOVE

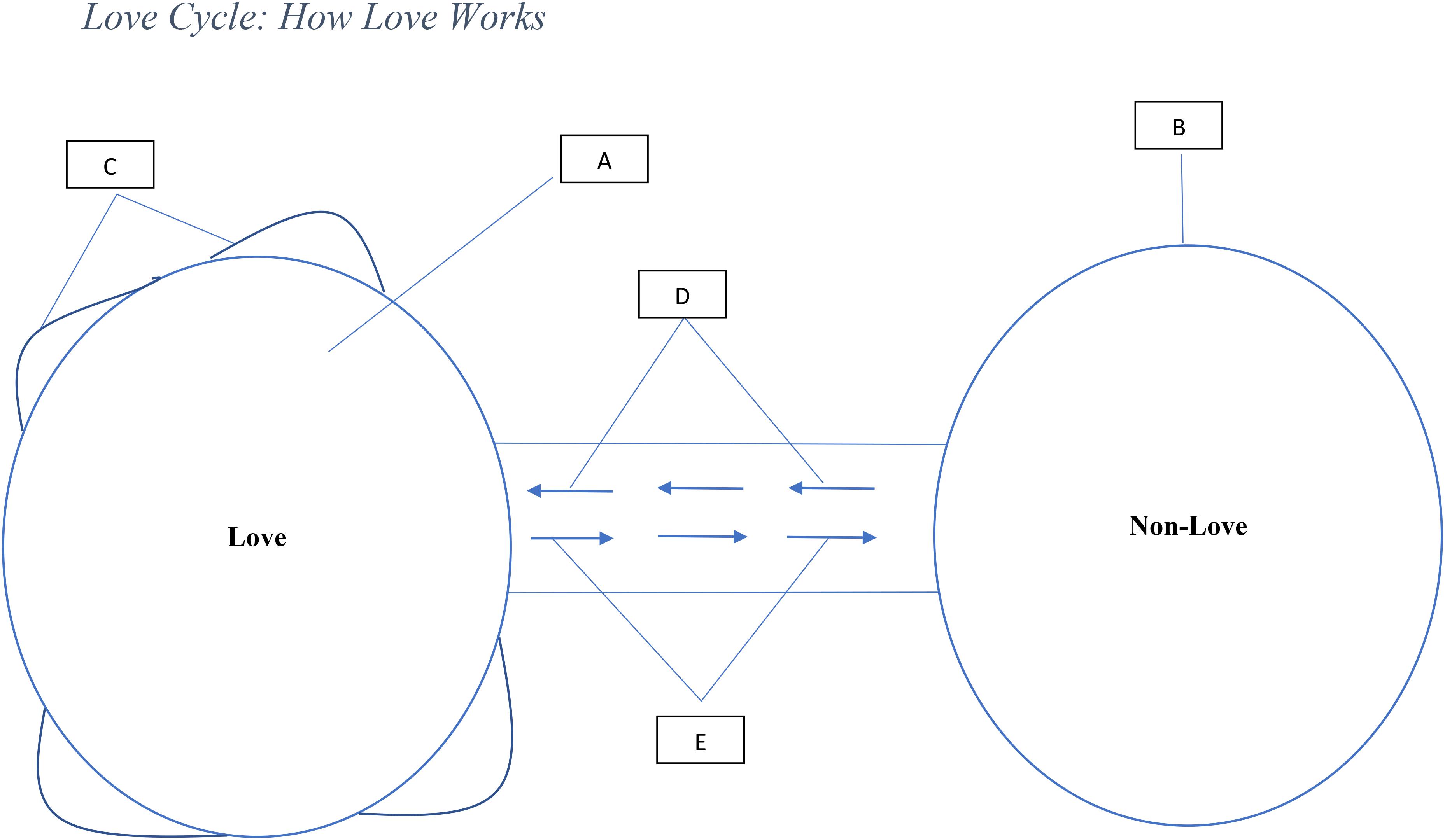

What is Love? According to authors, Reis and Aron, love is defined as a desire to enter, maintain, or expand a close, connected, and ongoing relationship with another person. Considerable evidence supports a basic distinction, first offered in 1978, between passionate love (“a state of intense longing for union with another”) and other types of romantic love, labeled companionate love (“the affection we feel for those with whom our lives are deeply entwined”).

The evidence for this distinction comes from a variety of research methods, including psychometric techniques, examinations of the behavioral and relationship consequences of different forms of romantic love, and biological studies, which are discussed in this article. Most work has focused on identifying and measuring passionate love and several aspects of romantic love, which include two components: intimacy and commitment. Some scholars see companionate love as a combination of intimacy and commitment, whereas others see intimacy as the central component, with commitment as a peripheral factor (but important in its own right, such as for predicting relationship longevity).

In some studies, trust and caring were considred highly prototypical of love, whereas uncertainty and butterflies in the stomach were more peripheral.

Passionate and companionate love solves different adaptation problems. Passionate love may be said to solve the attraction problem—that is, for individuals to enter into a potentially long-term mating relationship, they must identify and select suitable candidates, attract the other’s interest, engage in relationship-building behavior, and then go about reorganizing existing activities and relationships so as to include the other. All of this is strenuous, time-consuming, and disruptive. Consequently, passionate love is associated with many changes in cognition, emotion, and behavior. For the most part, these changes are consistent with the idea of disrupting existing activities, routines, and social networks to orient the individual’s attention and goal-directed behavior toward a specific new partner.

Considerably less study has been devoted to understanding the evolutionary significance of the intimacy and commitment aspects of love. However, much evidence indicates that love in long-term relationships is associated with intimacy, trust, caring, and attachment; all factors that contribute to the maintenance of relationships over time. More generally, the term companionate love may be characterized by communal relationship; a relationship built on mutual expectations that oneself and a partner will be responsive to each other’s needs.

It was speculated that companionate love, or at least the various processes associated with it, is responsible for the noted association among social relatedness, health, and well-being. In a recent series of papers, it was claimed that marriage is linked to health benefits. Having noted the positive functions of love, it is also important to consider the dark side. That is, problems in love and love relationships are a significant source of suicides, homicides, and both major and minor emotional disorders, such as anxiety and depression. Love matters not only because it can make our lives better, but also because it is a major source of misery and pain that can make life worse.

It is also believed that research will address how culture shapes the experience and expression of love. Although both passionate and companionate love appear to be universal, it is apparent that their manifestations may be moderated by culture-specific norms and rules.

Passionate love and companionate love has profoundly different implications for marriage around the world, considered essential in some cultures but contraindicated or rendered largely irrelevant in others. For example, among U.S. college students in the 1960s, only 24% of women and 65% of men considered love to be the basis of marriage, but in the 1980s this view was endorsed by more than 80% of both women and men.

Finally, the authors believe that the future will see a better understanding of what may be the quintessential question about love: How this very individualistic feeling is shaped by experiences in interaction with particular others.

Related Health Hunter News Articles

The Power of Nutrition: How Diet Shapes Long-Term Breast Cancer Survival

Hidden in Plain Sight: How to Support the Unseen Face of Cancer

Chia Flax Pumpkin Pudding

- Shop Nutrients

- ORDER LAB tests

You can see how this popup was set up in our step-by-step guide: https://wppopupmaker.com/guides/auto-opening-announcement-popups/

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Proximate and Ultimate Perspectives on Romantic Love

Geoff kushnick.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Ian D. Stephen, Macquarie University, Australia

Reviewed by: Severi Luoto, The University of Auckland, New Zealand; Cari Goetz, California State University, San Bernardino, United States; Norman Li, Singapore Management University, Singapore

*Correspondence: Adam Bode, [email protected]

† ORCID: Adam Bode, orcid.org/0000-0003-4593-5179 ; Geoff Kushnick, orcid.org/0000-0001-9280-0213

This article was submitted to Evolutionary Psychology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Received 2020 Jun 16; Accepted 2021 Mar 12; Collection date 2021.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

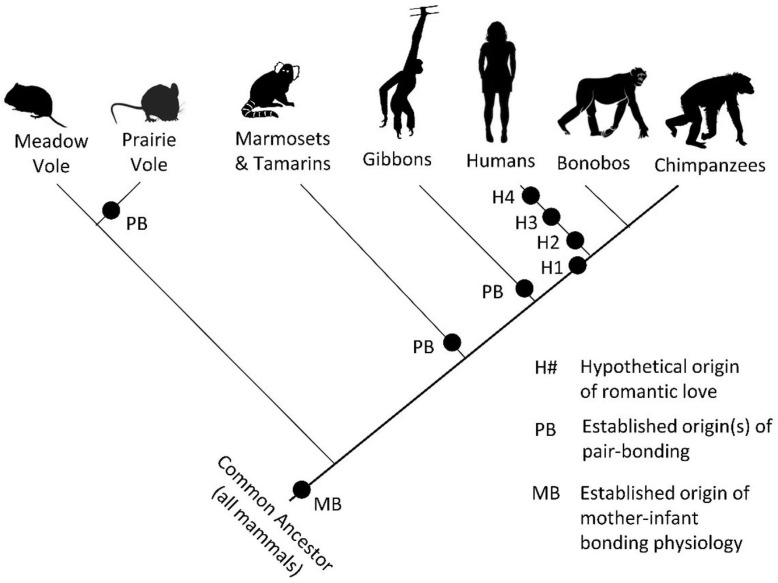

Romantic love is a phenomenon of immense interest to the general public as well as to scholars in several disciplines. It is known to be present in almost all human societies and has been studied from a number of perspectives. In this integrative review, we bring together what is known about romantic love using Tinbergen’s “four questions” framework originating from evolutionary biology. Under the first question, related to mechanisms, we show that it is caused by social, psychological mate choice, genetic, neural, and endocrine mechanisms. The mechanisms regulating psychopathology, cognitive biases, and animal models provide further insights into the mechanisms that regulate romantic love. Under the second question, related to development, we show that romantic love exists across the human lifespan in both sexes. We summarize what is known about its development and the internal and external factors that influence it. We consider cross-cultural perspectives and raise the issue of evolutionary mismatch. Under the third question, related to function, we discuss the fitness-relevant benefits and costs of romantic love with reference to mate choice, courtship, sex, and pair-bonding. We outline three possible selective pressures and contend that romantic love is a suite of adaptions and by-products. Under the fourth question, related to phylogeny, we summarize theories of romantic love’s evolutionary history and show that romantic love probably evolved in concert with pair-bonds in our recent ancestors. We describe the mammalian antecedents to romantic love and the contribution of genes and culture to the expression of modern romantic love. We advance four potential scenarios for the evolution of romantic love. We conclude by summarizing what Tinbergen’s four questions tell us, highlighting outstanding questions as avenues of potential future research, and suggesting a novel ethologically informed working definition to accommodate the multi-faceted understanding of romantic love advanced in this review.

Keywords: romantic love, mechanisms, ontogeny, functions, phylogeny, Tinbergen, human mating, definition

Introduction

Romantic love is a complex suite of adaptations and by-products that serves a range of functions related to reproduction ( Fletcher et al., 2015 ; Buss, 2019 ). It often occurs early in a romantic relationship but can lead to long-term mating. It is a universal or near-universal ( Jankowiak and Fischer, 1992 ; Gottschall and Nordlund, 2006 ; Jankowiak and Paladino, 2008 ; Fletcher et al., 2015 ; Buss, 2019 ; Sorokowski et al., 2020 ) and is characterized by a range of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, social, genetic, neural, and endocrine activity. It occurs across the lifespan in both sexes. Romantic love serves a variety of functions that vary according to life-stage and duration, including mate choice, courtship, sex, and pair-bonding. Its evolutionary history is probably coupled with the emergence of pair-bonds relatively recently in human evolutionary history.

Romantic love has received attention from scholars in diverse fields, including neurobiology, endocrinology, psychology, and anthropology. Our review aims to synthesize multiple threads of knowledge into a more well-rounded perspective on romantic love. To accomplish this, we do the following: First, we lay out our analytical framework based on Tinbergen’s (1963) “four questions” for explaining a biological phenomenon. Second, using this framework as an organizing tool, we summarize what is known about the social mechanisms, psychological mate choice mechanisms, genetics, neurobiology, endocrinology, development across the lifetime of an individual, fitness-relevant functions, and evolutionary history of romantic love. Finally, we conclude by summarizing what Tinbergen’s four questions tell us, identifying areas for future research, and providing a new ethologically informed working definition of romantic love.

Analytical Framework

Much work has been done to examine romantic love as a biological characteristic. Numerous reviews have described the neurobiology and endocrinology of romantic love (e.g., Fisher, 2004 , 2006 ; Zeki, 2007 ; Hatfield and Rapson, 2009 ; Reynaud et al., 2010 ; Cacioppo et al., 2012b ; de Boer et al., 2012 ; Diamond and Dickenson, 2012 ; Dunbar, 2012 ; Tarlaci, 2012 ; Xu et al., 2015 ; Fisher et al., 2016 ; Zou et al., 2016 ; Tomlinson et al., 2018 ; Walum and Young, 2018 ; Cacioppo, 2019 ). Two meta-analyses ( Ortigue et al., 2010 ; Cacioppo et al., 2012a ) considered fMRI studies of romantic love. There have been some accounts of romantic love or love from an evolutionary perspective (e.g., Hendrick and Hendrick, 1991 ; Fisher, 1995 , 2016 ; Fisher et al., 2006 , 2016 ; Kenrick, 2006 ; Lieberman and Hatfield, 2006 ; Schmitt, 2006 ; Fletcher et al., 2015 ; Sorokowski et al., 2017 ; Buss, 2019 ).

No one, however, has addressed the full spectrum of approaches used in biology to provide a comprehensive account of romantic love. We fill this gap by framing our review of romantic love around Tinbergen’s (1963) “four questions” for explaining biological traits. It was developed in the context of trying to provide a holistic, integrative understanding of animal behavior, and is an extension of earlier explanatory frameworks, including Mayr’s (1961) distinction between proximate and ultimate explanations in biology ( Bateson and Laland, 2013 ). It includes two proximate explanations, mechanistic and ontogenetic, and two ultimate (evolutionary) explanations, functional and phylogenetic. To illustrate the use of this framework, we refer to elements of Zeifman’s (2001) analysis of infant crying as a biological trait using this framework. An outline of our use of this framework is presented in Table 1 .

Summary of romantic love using Tinbergen’s (1963) framework.

Proximate explanations focus on the workings of biological and social systems and their components, both on a short-term (mechanistic) and longer-term (ontogenetic) basis ( Tinbergen, 1963 ; Zeifman, 2001 ). Mechanistic explanations attempt to answer questions about how behavior is produced by an organism. It is about the immediate causation of the behavior. A baby’s cry, under this class of explanation, might be viewed as an expression of emotion regulated by the limbic system. In our analysis, we ask: “What are the mechanisms that cause romantic love?” Ontogenetic explanations attempt to answer questions about how the behavior develops over the life course. A baby’s cry, thus, might be viewed as a vocalization that changes in frequency and context over the first year of life, and then across the rest of childhood. In our analysis, we ask: “How does romantic love develop over the lifetime of an individual?”

Ultimate explanations focus on the application of evolutionary logic to understand behavior, both on a short-term (functional) and long-term (phylogenetic) basis ( Tinbergen, 1963 ; Zeifman, 2001 ). Functional explanations attempt to answer questions about the fitness consequences of behavior and how it functions as an adaptation. A baby’s cry, thus, might be viewed as an adaptation that enhances offspring survival by eliciting care or providing information about its state. As the fitness consequences may be negative as well, it might focus on both benefits and costs. For instance, the cry may decrease survival by attracting predators or depleting scarce energy reserves. In our analysis, we ask: “What are the fitness-relevant functions of romantic love?” Phylogenetic explanations attempt to answer questions about the evolutionary history of a behavior and the mechanisms that produce it. A baby’s cry, thus, might be understood from the perspective of whether similar behaviors are present in closely related species. In our analysis, we ask: “What is the evolutionary history of romantic love?”

Tinbergen’s (1963) framework has been a useful tool for organizing research and theory on behavior and other biological traits across all major kingdoms of life, from plants (e.g., Satake, 2018 ) to humans (e.g., Winterhalder and Smith, 1992 ; Zeifman, 2001 ; Stephen et al., 2017 ; Luoto et al., 2019 ). It allows us to build holistic explanations of biological phenomena by examining complementary, but often non-mutually exclusive, categories of explanation ( Bateson and Laland, 2013 ). We believe that this approach to understanding romantic love will clarify the usefulness and interdependence of the various aspects of the biology of romantic love without falling into the pitfalls of posing explanations for the phenomena that are in opposition rather than complementary ( Nesse, 2013 ).

Definitions

There are a number of definitions and descriptions of romantic love. These definitions and descriptions have different names for romantic love, but all are attempting to define the same construct. We present, here, four definitions or descriptions of romantic love that continue to have relevance to contemporary research.

Walster and Walster (1978) were among the first to scientifically define romantic love. They gave it the name “passionate love” and their definition has been revised several times (e.g., Hatfield and Walster, 1985 ; Hatfield and Rapson, 1993 ). A definition of passionate love is:

A state of intense longing for union with another. Passionate love is a complex functional whole including appraisals or appreciations, subjective feelings, expressions, patterned physiological processes, action tendencies, and instrumental behaviors. Reciprocated love (union with the other) is associated with fulfillment and ecstasy; unrequited love (separation) with emptiness, anxiety, or despair ( Hatfield and Rapson, 1993 , p. 5).

Hendrick and Hendrick (1986) propose a description of romantic love in the context of describing six different “love styles” ( Lee, 1976 ). They label it “eros.” It too has undergone some changes. A recent version of the description is:

Strong physical attraction, emotional intensity, a preferred physical appearance, and a sense of inevitability of the relationship define the central core of eros. Eros can “strike” suddenly in a revolution of feeling and thinking ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 2019 , p. 244).

Sternberg (1986) provides a description of romantic love based on three components of love in close relationships: intimacy, passion and commitment. He calls it “romantic love” and describes it as such:

This kind of love derives from a combination of the intimacy and passion components of love. In essence, it is liking with an added element, namely, the arousal brought about by physical attraction and its concomitants. According to this view, then, romantic lovers are not only drawn physically to each other but are also bonded emotionally ( Sternberg, 1986 , p. 124).

A more recent definition of romantic love informed by evolutionary theory has been proposed by Fletcher et al. (2015) . Rather than providing a discrete series of sentences, they propose a working definition of “romantic love” that is explained with reference to some of the psychological research on romantic love and by summarizing five distinct features of romantic love. These features are:

Romantic love is a powerful commitment device, composed of passion, intimacy, and caregiving;

Romantic love is universal and is associated with pair-bonding across cultures;

Romantic love automatically suppresses effort and attention given to alternative partners;

Romantic love has distinct emotional, behavioral, hormonal, and neuropsychological features; and

Successful pair-bonding predicts better health and survival across cultures for both adults and offspring ( Fletcher et al., 2015 , p. 22).

Despite these attempts to define and describe romantic love, no single term or definition has been universally adopted in the literature. The psychological literature often uses the terms “romantic love,” “love,” and “passionate love” (e.g., Sternberg and Sternberg, 2019 ). Seminal work called it “limerence” ( Tennov, 1979 ). The biological literature generally uses the term “romantic love” and has investigated “early stage intense romantic love” (e.g., Xu et al., 2011 ), “long-term intense romantic love” (e.g., Acevedo et al., 2012 ), or being “in love” (e.g., Marazziti and Canale, 2004 ). In this review, what we term “romantic love” encompasses all of these definitions, descriptions, and terms. Romantic love contrasts with “companionate love,” which is felt less intensely, often follows a period of romantic love ( Hatfield and Walster, 1985 ), and merges feelings of intimacy and commitment ( Sternberg, 1986 ).

Psychological Characteristics

Hatfield and Sprecher (1986) theoretically developed the Passionate Love Scale to assess the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components of romantic love among people who are in a relationship. There are other ways of measuring romantic love ( Hatfield et al., 2012 ), and some, such as Sternberg’s Triangular Love Scale ( Sternberg, 1997 ; Sumter et al., 2013 ) or the Love Attitudes Scale ( Hendrick and Hendrick, 1986 ; Hendrick et al., 1998 ), measure the same constructs ( Masuda, 2003 ; Graham, 2011 ). The Passionate Love Scale is only valid in people who are in a romantic relationship with their loved one. Regardless, the Passionate Love Scale provides a particularly useful account of some of the psychological characteristics of romantic love. It has been used widely in research investigating romantic love in relationships ( Feybesse and Hatfield, 2019 ).

Cognitive components of romantic love include intrusive thinking or preoccupation with the partner, idealization of the other in the relationship, and desire to know the other and to be known. Emotional components include attraction to the other, especially sexual attraction, negative feelings when things go awry, longing for reciprocity, desire for complete union, and physiological arousal. Behavioral components include actions toward determining the other’s feelings, studying the other person, service to the other, and maintaining physical closeness ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ).

Romantic love shares a number of physiological and psychological characteristics with addiction. “[T]hey focus on their beloved (salience); and they yearn for their beloved (craving). They feel a “rush” of exhilaration when seeing or thinking about him or her (euphoria/intoxication). As their relationship builds, the lover experiences the common signs of drug withdrawal, too, including protest, crying spells, lethargy, anxiety, insomnia, or hypersomnia, loss of appetite or binge eating, irritability and chronic loneliness.” ( Fisher et al., 2016 , p. 2) A number of reviews have highlighted the behavioral and neurobiological similarities between addiction and romantic love (e.g., Reynaud et al., 2010 ; Fisher et al., 2016 ; Zou et al., 2016 ).

There is evidence that romantic love is associated with increased hypomanic symptoms (elevated mood, Brand et al., 2007 ; Bajoghli et al., 2011 , 2013 , 2014 , 2017 ; Brand et al., 2015 ), a change (increase or decrease) in depression symptoms ( Stoessel et al., 2011 ; Bajoghli et al., 2013 , 2014 , 2017 ; Price et al., 2016 ; Verhallen et al., 2019 ; Kuula et al., 2020 ), and increased state anxiety ( Hatfield et al., 1989 ; Wang and Nguyen, 1995 ; Bajoghli et al., 2013 , 2014 , 2017 ; Brand et al., 2015 ; Kuula et al., 2020 ). See Supplementary Table 1 for information about studies investigating hypomania, depression, and anxiety symptoms in people experiencing romantic love. Romantic love is also characterized by cognitive biases which resemble “positive illusions,” which are a tendency to perceive one’s relationship and one’s loved one in a positive light or bias ( Song et al., 2019 ).

Proximate Perspectives

When applied to romantic love, the first of Tinbergen’s (1963) four questions asks: “What are the mechanisms that cause romantic love?” This can be answered with reference to social mechanisms, psychological mate choice mechanisms, genetics, neurobiology, and endocrinology ( Zeifman, 2001 ; Bateson and Laland, 2013 ). Research into the social mechanisms and genetics of romantic love are in their infancy, but there is substantial theory on psychological mate choice mechanisms and ample research has been undertaken into the neural and endocrine activity associated with romantic love. Additional insights can be garnered from the neurobiology and endocrinology of psychopathology, cognitive biases, and animal models.

Social Mechanisms

Some precursors to romantic love (others discussed below) that act strongly as social mechanisms that cause romantic love are reciprocal liking, propinquity, social influence, and the filling of needs (e.g., Aron et al., 1989 ; Pines, 2001 ; Riela et al., 2010 ). Reciprocal liking (mutual attraction) is “being liked by the other, both in general, as well as when it is expressed through self-disclosure” ( Aron et al., 1989 , p. 245). It has been frequently identified as preceding romantic love among participants from the United States and is cross-culturally identified as the strongest preference in mates among both sexes ( Buss et al., 1990 ). “Whether expressed in a warm smile or a prolonged gaze, the message is unmistakable: ‘It’s safe to approach, I like you too. I’ll be nice. You’re not in danger of being rejected”’ ( Hazan and Diamond, 2000 , p. 197). Reciprocal liking may encourage the social approach and courtship activities characteristic and causative of romantic love.

Propinquity is “familiarity, in terms of having spent time together, living near the other, mere exposure to the other, thinking about the other, or anticipating interaction with the other” ( Aron et al., 1989 , p. 245). It has more recently been named “familiarity” (see Riela et al., 2010 ). The extended exposure of an individual to another helps to cause romantic love and specifically facilities the development of romantic love over extended periods of time. Propinquity, in our evolutionary history, served to ensure that “potential mates who are encountered daily at the river’s edge have an advantage over those residing on the other side” ( Hazan and Diamond, 2000 , p. 201). Given that the pool of potential mates in our evolutionary history would have been limited by the size of the groups in which we lived and the fact that most individuals of reproductive age would already have been involved in long-term mating relationships, propinquity is likely to have played a particularly important role in the generation of romantic love. Until recently (to a somewhat lesser extent, today), with the wide-scale take-up of online dating, propinquity played a role in the formation of many long-term pair-bonds, and presumably, romantic love, as is evidenced by a relatively high proportion of people having met their romantic partners in the places where exposure was facilitated, such as school, college, or work ( Rosenfeld et al., 2019 ). Changes in the importance of certain precursors in causing romantic love may be the result of a mismatch between the modern environment and our genotypes that evolved in a very different environment (discussed in detail below; see Li et al., 2018 ).

Social influences are “both general social norms and approval of others in the social network” ( Aron et al., 1989 , p. 245). This may cause people to fall in love with others who are of a similar attractiveness, cultural group, ethnic group, profession, economic class, or who are members of the same social group. Social influences may, directly, impact who we fall in love with by providing approval to a romantic union or, indirectly, by facilitating propinquity. The effect of social influences is demonstrated in the relatively large number of people who met their romantic partner through friends ( Rosenfeld et al., 2019 ). The filling of needs is “having the self’s needs met or meeting the needs of the other (e.g., he makes me happy, she buys me little presents that show she cares), and typically implies characteristics that are highly valued and beneficial in relationship maintenance (e.g., compassion, respect)” ( Riela et al., 2010 , pp. 474–475). The filling of needs may cause romantic love when social interaction facilitates a union where both partners complement each other.

Psychological Mate Choice Mechanisms

Mate choice, in the fields of evolutionary theory, can be defined as “the process that occurs whenever the effects of traits expressed in one sex lead to non-random allocation of reproductive investment with members of the opposite sex” ( Edward, 2015 , p. 301). It is essentially the process of intersexual selection proposed by Darwin (2013) more than 150 years ago ( Darwin, 1859 ) whereby someone has a preference for mating with a particular individual because of that individual’s characteristics. Mate choice, to that extent, involves the identification of a desirable conspecific ( Fisher et al., 2005 ) and sometimes, the focusing of mating energies on that individual. Mate preferences, sexual desire, and attraction all contribute to romantic love. The concepts of “extended phenotypes” and “overall attractiveness” help to explain how these features operate. Romantic love, as discussed below, serves a mate choice function ( Fisher et al., 2005 ) and these mechanisms and constructs contribute to when, and with whom, an individual falls in love.

A large body of research has developed around universal mate preferences (e.g., Buss and Barnes, 1986 ; Buss, 1989 ; Buss et al., 1990 ; Buss and Schmitt, 2019 ; Walter et al., 2020 ). Women, more than men, show a strong preference for resource potential, social status, a slightly older age, ambition and industriousness, dependability and stability, intelligence, compatibility, certain physical indicators, signs of good health, symmetry, masculinity, love, kindness, and commitment ( Buss, 1989 , 2016 ; Walter et al., 2020 ). Men, more than women, have preferences for youth, physical beauty, certain body shapes, chastity, and fidelity ( Buss, 1989 , 2016 ). Both sexes have particularly strong preferences for kindness and intelligence ( Buss et al., 1990 ). A male-taller-than-female norm exists in mate preferences and there is some evidence that women have a preference for taller-than-average height (e.g., Salska et al., 2008 ; Yancey and Emerson, 2014 ). Mutual attraction and reciprocated love are the most important characteristics that both women and men look for in a potential partner ( Buss et al., 1990 ).

Mate choice and attraction may be based on assessments of “extended phenotypes” ( Dawkins, 1982 ; Luoto, 2019a ), which include biotic and abiotic features of the environment that are influenced by an individual’s genes. For example, an extended phenotype would include an individual’s dwelling, car, pets, and social media presence. These can convey information relevant to fitness. Overall mate attractiveness, which is constituted by signs of health and fertility, neurophysiological efficiency, provisioning ability and resources, and capacity for cooperative relationships ( Miller and Todd, 1998 ) may be another heuristic through which attraction and mate choice operate.

Many mate preferences are relatively universal and therefore are likely to have at least some genetic basis (as suggested by, Sugiyama, 2015 ). While mate preferences are linked to actual mate selection ( Li et al., 2013 ; Li and Meltzer, 2015 ; Conroy-Beam and Buss, 2016 ; Buss and Schmitt, 2019 ), strong mate preferences do not always translate into real-world mate choice ( Todd et al., 2007 ; Stulp et al., 2013 ). This is in part because mate preferences function in a tradeoff manner whereby some preferences are given priority over others (see Li et al., 2002 ; Thomas et al., 2020 ). That is, mate choice is a multivariate process that includes the integration and tradeoff of several preferences ( Conroy-Beam et al., 2016 ). Mate preferences are important because they may serve as a means of screening potential mates, while sexual desire and attraction operationalize these preferences, and romantic love crystalizes them.

Sexual desire and attraction may be antecedents to falling in love and there is evidence that physiologically, sexual desire progresses into romantic love within shared neural structures ( Cacioppo et al., 2012a ). However, although both sexual desire and attraction operationalize mate choice, only attraction, and not sexual desire, may be necessary for romantic love to occur (see Leckman and Mayes, 1999 ; Diamond, 2004 ). Intense attraction is characterized by increased energy, focused attention, feelings of exhilaration, intrusive thinking, and a craving for emotional union ( Fisher, 1998 ) although it exists on a spectrum of intensity.

Changes in the expression of at least 61 genes are associated with falling in love in women ( Murray et al., 2019 ) suggesting that these genes may regulate features of romantic love. The DRD2 Taq I A polymorphism, which regulates Dopamine 2 receptor density ( Jonsson et al., 1999 ), is associated with eros ( Emanuele et al., 2007 ). Polymorphisms of genes that regulate vasopressin receptors (AVPR1a rs3), oxytocin receptors (OXTR rs53576), dopamine 4 receptors (DRD4-7R), and dopamine transmission (COMT rs4680) are associated with activity in the ventral tegmental area which, in turn, is associated with eros in newlyweds ( Acevedo et al., 2020 ).

Neurobiology

Neuroimaging studies (see Supplementary Table 2 ) implicate dozens of brain regions in romantic love. We focus, here, on only some of the most frequently replicated findings in an attempt to simplify a description of the neural activity associated with romantic love and explain its psychological characteristics. Romantic love, at least in people who are in a relationship with their loved one, appears to be associated with activity (activation or deactivation compared with a control condition) in four main overlapping systems: reward and motivation, emotions, sexual desire and arousal, and social cognition.

Reward and motivation structures associated with romantic love include those found in the mesolimbic pathway: the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and medial prefrontal cortex ( Xu et al., 2015 ). Activity in the mesolimbic pathway substantiates the claim that romantic love is a motivational state ( Fisher et al., 2005 ) and helps to explain why romantic love is characterized by psychological features such as longing for reciprocity, desire for complete union, service to the other, maintaining physical closeness, and physiological arousal ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ).

Emotional centers of the brain associated with romantic love include the amygdala, the anterior cingulate cortex ( Bartels and Zeki, 2000 ; Aron et al., 2005 ; Fisher et al., 2010 ; Younger et al., 2010 ; Zeki and Romaya, 2010 ; Stoessel et al., 2011 ; Acevedo et al., 2012 ; Scheele et al., 2013 ; Song et al., 2015 ), and the insula ( Bartels and Zeki, 2000 ; Aron et al., 2005 ; Ortigue et al., 2007 ; Fisher et al., 2010 ; Younger et al., 2010 ; Zeki and Romaya, 2010 ; Stoessel et al., 2011 ; Acevedo et al., 2012 ; Xu et al., 2012b ; Song et al., 2015 ). Activity in these structures helps to explain romantic love’s emotional features such as negative feelings when things go awry, longing for reciprocity, desire for complete union, and physiological arousal ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ).

The primary areas associated with both romantic love and sexual desire and arousal include the caudate, insula, putamen, and anterior cingulate cortex ( Diamond and Dickenson, 2012 ). The involvement of these regions helps to explain why people experiencing romantic love feel extremely sexually attracted to their loved one ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ). The neural similarities and overlapping psychological characteristics of romantic love and sexual desire are well documented (see Hatfield and Rapson, 2009 ; Cacioppo et al., 2012a ; Diamond and Dickenson, 2012 ).

Social cognition centers in the brain repeatedly associated with romantic love include the amygdala, the insula ( Adolphs, 2001 ), and the medial prefrontal cortex ( Van Overwalle, 2009 ). Social cognition plays a role in the social appraisals and cooperation characteristics of romantic love. Activity in these regions helps to explain psychological characteristics such as actions toward determining the other’s feelings, studying the other person, and service to the other ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ).

In addition to activity in these four systems, romantic love is associated with activity in higher-order cortical brain areas that are involved in attention, memory, mental associations, and self-representation ( Cacioppo et al., 2012b ). Mate choice (a function of romantic love detailed below) has been specifically associated with the mesolimbic pathway and hypothalamus ( Calabrò et al., 2019 ). The mesolimbic pathway, thalamus, hypothalamus, amygdala, septal region, prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, and insula have been specifically associated with human sexual behavior ( Calabrò et al., 2019 ), which has implications for the sex function of romantic love (detailed below).

Isolated studies have identified sex differences in the neurobiological activity associated with romantic love. One study ( Bartels and Zeki, 2004 ) found activity in the region ventral to the genu in only women experiencing romantic love. One preliminary study of romantic love (see Fisher et al., 2006 ) found that “[m]en tended to show more activity than women in a region of the right posterior dorsal insula that has been correlated with penile turgidity and male viewing of beautiful faces. Men also showed more activity in regions associated with the integration of visual stimuli. Women tended to show more activity than men in regions associated with attention, memory and emotion” (p. 2181).

Endocrinology

Romantic love is associated with changes in circulating sex hormones, serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin, cortisol, and nerve growth factor systems. Table 2 presents the endocrine factors which are found to be different, compared to controls, in people experiencing romantic love. More information about the controlled studies discussed in this subsection is presented in Supplementary Table 3 . Endocrine factors associated with romantic love have most of their psychological and other effects because of their role as a hormone (e.g., sex hormones, cortisol) or neurotransmitter (e.g., serotonin, dopamine), although many factors operate as both (see Calisi and Saldanha, 2015 ) or as neurohormones.

Significant results of controlled endocrine studies investigating romantic love.

<, lower level than control; >, higher level than controls; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; NGF, nerve growth factor; LH, luteinizing hormone; *, decreased transporter density is indicative of higher extracellular neurotransmitter levels.

Romantic love is associated with changes in the sex hormones testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone ( Marazziti and Canale, 2004 ; Durdiakova et al., 2017 ; Sorokowski et al., 2019 ), although the findings have been inconsistent. Testosterone appears to be lower in men experiencing romantic love than controls ( Marazziti and Canale, 2004 ) and higher eros scores are associated with lower levels of testosterone in men ( Durdiakova et al., 2017 ). Lower levels of testosterone in fathers are associated with greater involvement in parenting (see Storey et al., 2020 , for review). The direction of testosterone change in women is unclear (see Marazziti and Canale, 2004 ; Sorokowski et al., 2019 ). Sex hormones are involved in the establishment and maintenance of sexual characteristics, sexual behavior, and reproductive function ( Mooradian et al., 1987 ; Chappel and Howles, 1991 ; Holloway and Wylie, 2015 ). Some sex hormones can influence behavior through their organizing effects resulting from prenatal and postnatal exposure. In the case of romantic love, however, the effects of sex hormones on the features of romantic love are the result of activating effects associated with behaviorally contemporaneous activity. It is possible that sex hormones influence individual differences in the presentation of romantic love through their organizing effect (see Motta-Mena and Puts, 2017 ; Luoto et al., 2019 ; Arnold, 2020 ; McCarthy, 2020 , for descriptions of organizing and activating effects of testosterone, estradiol, and progesterone). Changes in sex hormones could help to explain the increase in sexual desire and arousal associated with romantic love ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ; Hatfield and Rapson, 2009 ; Diamond and Dickenson, 2012 ).

Romantic love is associated with decreased serotonin transporter density ( Marazziti et al., 1999 ) and changes in plasma serotonin ( Langeslag et al., 2012 ), although inconsistencies have been found in the direction of change according to sex. In one study, men experiencing romantic love displayed lower serotonin levels than controls and women displayed higher serotonin levels than controls ( Langeslag et al., 2012 ). Decreased serotonin transporter density is indicative of elevated extracellular serotonin levels ( Mercado and Kilic, 2010 ; Jørgensen et al., 2014 ). However, decreased levels of serotonin are thought to play a role in depression, mania, and anxiety disorders ( Mohammad-Zadeh et al., 2008 ), including obsessive-compulsive disorder (for a discussion of the relationship between serotonin and OCD, see Baumgarten and Grozdanovic, 1998 ; Rantala et al., 2019 ). One study showed that a sample of mainly women (85% women) experiencing romantic love have similar levels of serotonin transporter density to a sample of both women and men (50% women) with obsessive-compulsive disorder ( Marazziti et al., 1999 ), which could account for the intrusive thinking or preoccupation with the loved one associated with romantic love ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ).

Lower dopamine transporter density and lower dopamine transporter maximal velocity in lymphocytes have been found in people experiencing romantic love ( Marazziti et al., 2017 ). This is indicative of increased dopamine levels ( Marazziti et al., 2017 ) and is consistent with neuroimaging studies (e.g., Takahashi et al., 2015 ; Acevedo et al., 2020 ) showing activation of dopamine-rich regions of the mesolimbic pathway. One study ( Dundon and Rellini, 2012 ) found no difference in dopamine levels in urine in women experiencing romantic love compared with a control group. Dopamine is involved in reward behavior, sleep, mood, attention, learning, pain processing, movement, emotion, and cognition ( Ayano, 2016 ). Up-regulation of the dopamine system could help to explain the motivational characteristics of romantic love such as longing for reciprocity, desire for complete union, service to the other, and maintaining physical closeness ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ).

There are no studies that have specifically investigated oxytocin levels in romantic love (at least none that measure romantic love with a validated scale). However, studies ( Schneiderman et al., 2012 , Schneiderman et al., 2014 ; Ulmer-Yaniv et al., 2016 ) have demonstrated that people in the early stages of their romantic relationship have higher levels of plasma oxytocin than controls (singles and new parents). We infer this to mean that reciprocated romantic love is associated with elevated oxytocin levels. Oxytocin plays a role in social affiliation ( IsHak et al., 2011 ) and pair-bonding ( Young et al., 2011 ; Acevedo et al., 2020 ). Oxytocin receptors are prevalent throughout the brain including in the mesolimbic pathway (e.g., Bartels and Zeki, 2000 ). Elevated oxytocin could account for many of the behavioral features of romantic love such as actions toward determining the other’s feelings, studying the other person, service to the other, and maintaining physical closeness ( Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 ).

Romantic love has been associated with elevated cortisol levels ( Marazziti and Canale, 2004 ), although this has not been replicated ( Sorokowski et al., 2019 ), and one study measuring cortisol in saliva found the opposite ( Weisman et al., 2015 ). Different results could be attributed to different length of time in a relationship between the samples (see Garcia, 1997 ; de Boer et al., 2012 ). Cortisol plays a role in the human stress response by directing glucose and other resources to various areas of the body involved in responding to environmental stressors while simultaneously deactivating other processes (such as digestion and immune regulation, Mercado and Hibel, 2017 ). Elevated cortisol levels may play a role in pair-bond initiation ( Mercado and Hibel, 2017 ) and are indicative of a stressful environment.

Romantic love is associated with higher levels of nerve growth factor, and the intensity of romantic love correlates with levels of nerve growth factor ( Emanuele et al., 2006 ). Nerve growth factor is a neurotrophic implicated in psycho-neuroendocrine plasticity and neurogenesis ( Berry et al., 2012 ; Aloe et al., 2015 ; Shohayeb et al., 2018 ) and could contribute to some of the neural and endocrine changes associated with romantic love.

Insights From the Mechanisms of Psychopathology

Despite “madness” being mentioned in one review of the neurobiology of love ( Zeki, 2007 ) and psychopathology being discussed in studies investigating the endocrinology of romantic love (e.g., Marazziti et al., 1999 , 2017 ), the similarities between romantic love and psychopathology are under-investigated. An understanding of the mechanisms that regulate addiction, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders may help to shed light on the psychological characteristics and mechanisms underlying romantic love and identify areas for future research.

Conceptualizing romantic love as a “natural addiction” (e.g., Fisher et al., 2016 ) not only helps to explain romantic love’s psychological characteristics but provides insight into the mechanisms underlying it (e.g., Zou et al., 2016 ). For example, a neurocircuitry analysis of addiction, drawing on human and animal studies, reveals mechanisms of different “stages” of addiction that have implications for romantic love: binge/intoxication (encompassing drug reward and incentive salience), withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation ( Koob and Volkow, 2016 ). Each of these stages is associated with particular neurobiological activity and each stage could be represented in romantic love. This may mean that the findings of studies investigating the neurobiology of romantic love (which rely primarily on studies where visual stimuli of a loved one are presented) equates to the binge/intoxication stage of addiction. Findings from studies investigating romantic rejection ( Fisher et al., 2010 ; Stoessel et al., 2011 ; Song et al., 2015 ) may equate to the withdrawal/negative affect stage of addiction. Findings from resting-state fMRI studies ( Song et al., 2015 ; Wang et al., 2020 ) may equate to the preoccupation/anticipation stage of addiction. The result is that current neuroimaging studies may paint a more detailed picture of the neurobiology of romantic love than might initially be assumed.

Mood is an emotional predictor of the short-term prospects of pleasure and pain ( Morris, 2003 ). The adaptive function of mood is, essentially, to integrate information about the environment and state of the individual to fine-tune decisions about behavioral effort ( Nettle and Bateson, 2012 ). Elevated mood can serve to promote goal-oriented behavior and depressed mood can serve to extinguish such behavior ( Wrosch and Miller, 2009 ; Bindl et al., 2012 ; Nesse, 2019 ). Anxious mood is a response to repeated threats ( Nettle and Bateson, 2012 ). Because romantic love can be a tumultuous time characterized by emotional highs, lows, fear, and trepidation, and can involve sustained and repetitive efforts to pursue and retain a mate, it follows that mood circuitry would be closely intertwined with romantic love. Additionally, because romantic love concerns itself with reproduction, which is the highest goal in the realm of evolutionary fitness, it makes sense that mood may impact upon the way romantic love manifests. Understanding the mechanisms that regulate mood can provide insights into psychological characteristics of romantic love and the mechanisms that regulate it. No studies have directly investigated the mechanisms that contribute to changes in mood in people experiencing romantic love. However, insights can be taken from research into the mechanisms of mood and anxiety disorders.

While addiction, hypomania, depression, and anxiety symptoms in people experiencing romantic love may be the normal manifestation of particular mechanisms, symptoms associated with psychopathology may be the manifestations of malfunctioning mechanisms as a result of evolutionary mismatch (see Durisko et al., 2016 ; Li et al., 2018 ). As a result, the mechanisms that cause romantic love and those that cause psychopathology may not be precise models with which to investigate the other. Nonetheless, the mechanisms that cause psychopathology may provide a useful framework with which to base future research into romantic love. Conversely, it may also be that our understanding of the mechanisms that cause romantic love could be a useful framework with which to further investigate psychopathology.

The drug reward and incentive salience features of the binge/intoxication stage of addiction involve changes in dopamine and opioid peptides in the basal ganglia (i.e., striatum, globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and substantia nigra pars reticulata, Koob and Volkow, 2016 ). No research has investigated opioids in romantic love, despite them being involved in monogamy in primates (see French et al., 2018 ) and pair-bonding in rodents ( Loth and Donaldson, 2021 ). The negative emotional states and dysphoric and stress-like responses in the withdrawal/negative affect stage are caused by decreases in the function of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway and recruitment of brain stress neurotransmitters (i.e., corticotropin-releasing factor, dynorphin), in the extended amygdala ( Koob and Volkow, 2016 ). No studies have investigated corticotropin-releasing factor in romantic love. The craving and deficits in executive function in the preoccupation/anticipation stage of addiction involve the dysregulation of projections from the prefrontal cortex and insula (e.g., glutamate), to the basal ganglia and extended amygdala ( Koob and Volkow, 2016 ). No studies have investigated glutamate in romantic love. There are at least 18 neurochemically defined mini circuits associated with addiction ( Koob and Volkow, 2016 ) that could be the target of research into romantic love. It is likely that romantic love has similar, although not identical, mechanisms to addiction (see Zou et al., 2016 ; Wang et al., 2020 ).

Mania/hypomania (bipolar disorder)

Similar to the brain regions implicated in romantic love, the ventral tegmental area has been associated with mania ( Abler et al., 2008 ), the ventral striatum has been associated with bipolar disorder ( Dutra et al., 2015 ), and the amygdala has been associated with the development of bipolar disorder ( Garrett and Chang, 2008 ). These findings should be interpreted with caution, however, as replicating neuroimaging findings in bipolar disorder has proven difficult (see Maletic and Raison, 2014 ). Research implicates two interrelated prefrontal–limbic networks in elevated mood, which overlap with activity found in romantic love: the automatic/internal emotional regulatory network which includes the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, nucleus accumbens, globus pallidus, and the thalamus, and the volitional/external regulatory network which includes the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, mid- and dorsal-cingulate cortex, ventromedial striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus ( Maletic and Raison, 2014 ).

Norepinephrine (theorized to be involved in romantic love, e.g., Fisher, 1998 , 2000 ), serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine play a role in bipolar disorder ( Manji et al., 2003 ). One study ( Dundon and Rellini, 2012 ) found no difference in norepinephrine levels in urine in women experiencing romantic love compared with a control group. No studies have investigated acetylcholine in romantic love but romantic love is associated with serotonin ( Marazziti et al., 1999 ; Langeslag et al., 2012 ) and dopamine activity ( Marazziti et al., 2017 ). Similar to the endocrine factors implicated in romantic love ( Emanuele et al., 2006 ; Schneiderman et al., 2012 , 2014 ; Ulmer-Yaniv et al., 2016 ), bipolar patients in a period of mania have also demonstrated higher oxytocin ( Turan et al., 2013 ) and nerve growth factor ( Liu et al., 2014 ) levels and lower levels of serotonin ( Shiah and Yatham, 2000 ). Additionally, there is some evidence that women diagnosed with bipolar disorder present with higher levels of testosterone whereas men present with lower levels of testosterone compared with sex-matched controls ( Wooderson et al., 2015 ). Similar findings have been found in romantic love ( Marazziti and Canale, 2004 ). Dysfunction in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, where cortisol plays a major role, has also been implicated in bipolar disorder ( Maletic and Raison, 2014 ). Cortisol probably plays a role in romantic love ( Marazziti and Canale, 2004 ; Weisman et al., 2015 ).

Neuroimaging studies have implicated changes in functional connectivity in the neural circuits involved in affect regulation in people experiencing depression ( Dean and Keshavan, 2017 ). Increased functional connectivity has been found in networks involving some of the same regions, such as the amygdala, the medial prefrontal cortex, and nucleus accumbens in both people experiencing romantic love and people who recently ended their relationship while in love ( Song et al., 2015 ).

There are a number of endocrine similarities between romantic love and depression. One major pathophysiological theory of depression is that it is caused by an alteration in levels of one or more monoamines, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine ( Dean and Keshavan, 2017 ). Altered dopamine transmission in depression may be characterized by a down-regulated dopamine system (see Belujon and Grace, 2017 ), which is inferred from numerous human and animal studies, including successful treatment in humans with a dopamine agonist. In romantic love, however, dopamine appears to be up-regulated, especially in areas of the mesolimbic pathway (e.g., Marazziti et al., 2017 ; Bartels and Zeki, 2000 ; Acevedo et al., 2020 ). This could account for some findings that romantic love is associated with a reduction in depression symptoms ( Bajoghli et al., 2013 , 2017 ). However, these need to be reconciled with contrasting findings that romantic love is associated with increased depression symptoms ( Bajoghli et al., 2014 ; Kuula et al., 2020 ) and evidence suggesting that a relationship breakup in people experiencing romantic love is associated with depression symptoms ( Stoessel et al., 2011 ; Price et al., 2016 ; Verhallen et al., 2019 ). The mechanisms that underlie depression might provide a framework for such efforts.

Dysregulation of the HPA axis and associated elevated levels of cortisol is theorized to be one contributor to depression ( Dean and Keshavan, 2017 ). Changes in oxytocin and vasopressin systems (theorized to be involved in romantic love, e.g., Fisher, 1998 , 2000 ; Carter, 2017 ; Walum and Young, 2018 ) are associated with depression (see Purba et al., 1996 ; Van Londen et al., 1998 ; Neumann and Landgraf, 2012 ; McQuaid et al., 2014 ). No studies have investigated vasopressin in people experiencing romantic love. There is also decreased neurogenesis and neuroplasticity in people experiencing depression ( Dean and Keshavan, 2017 ), the opposite of which can be inferred to occur in romantic love because of its substantial neurobiological activity and elevated nerve growth factor (see Berry et al., 2012 ; Aloe et al., 2015 ; Shohayeb et al., 2018 ).

The insular cortex, cingulate cortex, and amygdala are implicated in anxiety and anxiety disorders ( Martin et al., 2009 ). There is also evidence that cortisol, serotonin and norepinephrine are involved ( Martin et al., 2009 ). The substantial overlap between the mechanisms regulating romantic love and those causing anxiety and anxiety disorders provides an opportunity to investigate specific mechanistic effects on the psychological characteristics of romantic love. Assessing state anxiety and these mechanisms concurrently in people experiencing romantic love may be a fruitful area of research.

There is also a need to clarify the role of the serotonin system in romantic love. Similar serotonin transporter density in platelets in people experiencing romantic love and OCD suggests a similar serotonin-related mechanism in both ( Marazziti et al., 1999 ). However, lower serotonin transporter density in platelets is indicative of higher extracellular serotonin levels ( Mercado and Kilic, 2010 ; Jørgensen et al., 2014 ). This is despite lower levels of serotonin being theorized to contribute to anxiety ( Mohammad-Zadeh et al., 2008 ). One study found lower circulating serotonin levels in men experiencing romantic love than controls and higher levels of circulating levels of serotonin in women experiencing romantic love than controls ( Langeslag et al., 2012 ). Insights from the mechanisms regulating anxiety disorders may help to provide a framework with which to further investigate the role of the serotonin system in romantic love and reconcile these findings.

Insights From Cognitive Biases

Positive illusions are cognitive biases about a relationship and loved one that are thought to have positive relationship effects ( Song et al., 2019 ). The research into positive illusions does not use samples of people explicitly experiencing romantic love, and instead uses people in varied stages of a romantic relationship, including those in longer-term pair-bonds. One study ( Swami et al., 2009 ), however, did find a correlation between the “love-is-blind bias” (one type of positive illusion) and eros scores. We also know that cognitive biases resembling positive illusions do exist in romantic love. Both the Passionate Love Scale (e.g., “For me, ____ is the perfect romantic partner,” Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986 , p. 391) and the eros subscale of the Love Attitudes Scale (e.g., “My lover fits my ideal standards of physical beauty/handsomeness,” Hendrick and Hendrick, 1986 , p. 395) include questions about a respondent’s loved one that resemble measures of positive illusions. Understanding the mechanism that regulates positive illusions will provide a model against which the mechanisms regulating the cognitive features of romantic love can be assessed.