Gun Violence Must Stop. Here's What We Can Do to Prevent More Deaths

Listen to "How Communities Can Prevent Gun Violence," a Prevention Institute podcast episode

Time and again, we are heartbroken by the news of another mass shooting. Part of our healing must be the conviction that we will do everything in our power to keep these tragedies from happening in a nation that continues to face a pandemic of gun violence. It's not only the high-profile mass shootings that we must work to prevent, but also the daily death-by-guns that claims more than 30,000 lives every year.

We know that these deaths are a predictable outcome of our country’s lack of political will to make a change and an underinvestment in prevention approaches that work. Through a public health approach that focuses on drawing from evidence and addressing the factors that increase or decrease the risk of gun violence, particularly in communities that are disproportionately impacted, we can save lives.

Each time a major tragedy occurs, the discourse tends to focus on addressing a specific venue. In the wake of the deadly shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas School in Parkland, Florida on February 14, 2018, there is an understandable focus on school safety. We strongly support broad engagement of community members, including young people and other survivors of gun violence, policymakers, and others, in insisting that schools be safe. We must also insist on that same level of safety for our places of worship, shopping malls, movie theaters, concert venues, nightclubs, workplaces, neighborhoods, and homes.

We are listening to young people from all races, classes, and sexualities, in Florida, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and throughout the country, who are unifying to speak truth to power. We have renewed hope that, together, we can prevent gun violence— not just in the case of mass shootings but also in the case of domestic violence, suicide, community violence, and violence involving law enforcement. We first developed this list after the Sandy Hook tragedy in 2012. The public health approach has evolved since then, and we have now updated it, including more attention to addressing multiple forms of gun violence.

The recommendations below begin with attention to reducing immediate risks related to guns, broaden to address the underlying contributors to gun violence, and then address the prevention infrastructure necessary to ensure effectiveness. We also include recommendations related to new frontiers for research and practice, to ensure that we continue to learn, innovate, and increase our impact over time. The set of recommendations illustrate that one program or policy alone is not going to significantly reduce gun violence, but rather, through comprehensive strategies, we can achieve safety in our homes, schools, and communities.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

Gun safety: Reduce the imminent risk of lethality through sensible gun laws and a culture of safety.

1. Sensible gun laws: Reduce easy access to dangerous weapons.

2. Establish a culture of gun safety.

- Reduce firearm access to youth and individuals who are at risk of harming themselves or others.

- Hold the gun industry accountable and ensure there is adequate oversight over the marketing and sales of guns and ammunition.

- Engage responsible gun dealers and owners in solutions.

- Insist on mandatory training and licensing for owners.

- Require safe and secure gun storage.

Underlying contributors to gun violence: systematically reduce risks and increase resilience in individuals, families, and communities.

3. Public health solutions: Recognize gun violence as a critical and preventable public health problem.

4. Comprehensive solutions: Support community planning and implementation of comprehensive community safety plans that include prevention and intervention.

5. Trauma, connection, and services: Expand access to high quality, culturally competent, coordinated, social, emotional, and mental health supports and address the impact of trauma.

Prevention Infrastructure: ensure effectiveness and sustainability of efforts

6. Support gun violence research: Ensure that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and others have the resources to study this issue and provide science-based guidance.

7. Health system: Establish a comprehensive health system in which violence prevention is a health system responsibility and imperative.

New Frontiers: continue to learn, innovate, and increase impact through research and practice

8. Community healing: Prevent community trauma.

9. Mental health and wellbeing: Invest in communities to promote resilience and mental health and wellbeing.

10. Support health y norms about masculinity: Explore the pathways between gun violence and harmful norms that have been about maintaining power and privilege.

11. Impulsive anger: Explore the linkages between anger and gun violence.

12. Economic development: Reduce concentrated disadvantage and invest in employment opportunities.

13. Law enforcement violence: Establish accountability for sworn officers and private security.

14. Technology: Advance gun safety and self-defense technology.

FULL RECOMMENDATIONS for Preventing Gun Violence

Gun safety: Part of a public health approach to gun violence is about preventing the imminent risk of lethality through sensible gun laws and a culture of safety.

- Sensible gun laws: Reduce easy access to dangerous weapons by banning high capacity magazines and bump stocks, requiring universal background checks without loopholes, instituting waiting periods , and reinstituting the assault weapons ban immediately.

- Establish a culture of gun safety: As the nation on earth with the most guns, we must make sure people are safe.

- Reduce firearm access to youth and individuals who are at risk of harming themselves or others . This includes keeping guns out of the hands of those who have been violent toward their partners and families, and those with previous violent convictions, whether through expanding lethality assessment and background checks or supporting domestic violence bills , and gun violence restraining orders .

- Hold the gun industry accountable and ensure there is adequate oversight over the marketing and sales of guns and ammunition . Five percent of gun dealers sell 90% of guns used in crimes, and must be held accountable to a code of conduct . Further, states can pass laws requiring sellers to obtain state licenses, maintain records of sales, submit to inspections and fulfill other requirements. Unlike other industries, gun companies have special legal protections against liability leaving them immune from lawsuits. There is a need to repeal gun industry immunity laws in states that have them, and resist their enactment in states without current immunity laws. Increasingly, in the absence of legislative action, organizations are divesting from companies that manufacture firearms, and consumers are pressuring companies directly. More and more companies are setting new policies about what they are selling to the public and/or who they are selling products to.

- Engage responsible gun dealers and owners in solutions. For example, some gun dealers and range owners are already being trained in suicide prevention .

- Insist on mandatory training and licensing for owners . This training should include recurring education to renew permits, with a graduated licensing process at least as stringent as for driver's licenses.

- Require safe and secure gun storage. For example, in King County, Washington, public health has teamed up with firearm storage device retailers. In addition to safe storage being tax exempt in Washington, through the LOK-IT-UP initiative , residents can learn about the importance of safe storage, purchase devices at discounted rates and learn how to practice safe storage in the home.

Underlying contributors to gun violence: Risk and resilience. A public health approach to preventing gun violence expands solutions beyond gun access to reduce additional risk factors associated with gun violence and bolster resilience in individuals, families, and communities.

- Public health solutions: Recognize gun violence as a critical and preventable public health problem. Gun violence is a leading cause of premature death in the country. Yet, unlike other preventable causes of death, we haven't mustered the political will to address it. Gun violence is most noticed when multiple people die at once, but it affects too many communities and families on a daily basis whether through suicide, domestic violence, community violence, or other forms. Data shows that risk for firearm violence varies substantially by age, race, gender, and geography, in patterns that are quite different for suicide and homicide. Through a public health approach, we have learned that violence is preventable across all of its forms. The public health approach studies data on various forms of violence and who is affected and identifies the biggest risk factors and what’s protective, and develops policy, practice, and program solutions in partnership with other sectors and community members. Many communities and groups have adopted a public health approach to preventing violence such as Prevention Institute’s UNITY City Network and Cities United , a growing network of over 100 mayors.

- Comprehensive solutions: Support community planning and implementation of comprehensive community safety plans that include prevention and intervention. A growing research base demonstrates that it is possible to prevent shootings and killings through approaches such as hospital-based intervention programs , the Cure Violence model , and Advance Peace . A growing number of safety plans across the country include upstream strategies such as youth employment , neighborhood economic development, safe parks , restoring vacant land , and reducing alcohol outlet density . Following the implementation of Minneapolis’ Blueprint for Action to Prevent Youth Violence , which prioritized prevention and upstream strategies, the City experienced a 62% reduction in youth gunshot victims, a 34% reduction in youth victims of crime, and a 76% reduction in youth arrests with a gun from 2007-2015. Yet too many communities lack the resources to do what is needed. We must commit to helping communities identify and implement solutions.

- Trauma, connection, and services: Expand access to high quality, culturally competent, coordinated, social, emotional, and mental health supports and a ddress the impact of trauma. Too often gun violence is blamed on mental illness, when in fact in most cases people who carry out shootings do not have a diagnosable mental illness. However, throughout a community, members often recognize individuals who are disconnected and/or otherwise in need of additional supports and services. It is critical to reduce the stigma associated with mental health needs and support our children, friends, family members, and neighbors in seeking and obtaining appropriate supports. For this to work, communities need resources to assess and connect individuals at a high risk for harming themselves or others to well-coordinated social, emotional, and mental health supports and services, particularly in critical times of crisis and high need. Further, trauma can have damaging effects on learning, behavior, and health across the life course, especially during key developmental stages such as early childhood and adolescence, and can increase the risk for multiple forms of violence . We need to do more to recognize trauma, develop trauma-informed protocols, including for law enforcement, and support healing and treatment for individuals who have experienced or are experiencing trauma, including from exposure to violence in any form.

Prevention Infrastructure: Beyond addressing the risk and underlying factors of gun violence, a public health approach also entails building a prevention infrastructure with mechanisms for scale, sustainability, and effectiveness. The UNITY RoadMap is a tool to support prevention infrastructure.

- Support gun violence research: Ensure that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and others have the resources to study this issue and provide science-based guidance. The CDC, the nation's public health agency, has long been restricted from conducting the kind of research that will support solutions to reduce gun violence. CDC can track, assess, and develop strategies to prevent gun violence, just as we do with influenza and tainted spinach. In the absence of sufficient tracking and evidence at the federal level, California launched the Firearm Violence Prevention Research Center at UC Davis, and other states are proposing to establish research centers as well.

- Health system: Establish a comprehensive health system in which violence prevention is a health system responsibility and imperative. The Movement towards Violence as a Health Issue , which consists of over 400 individuals representing more than 100 organizations across the country dedicated to a health and community response to violence has proposed a framework for addressing and preventing violence in all of its forms. Moving away from the current, fragmented approach to violence that leans heavily on the justice system, this unifying framework encourages and supports extensive cross-sector collaboration. The framework includes 18 system elements such as public health departments, primary care, behavioral health care, law enforcement and the justice system, schools, and faith-based institutions, which together can move the nation toward safety, health, and equity.

New Frontiers: A public health approach includes continuous learning and innovation to increase impact through research and practice. These emerging areas require further examination and are important additions to reducing the impact of gun violence in our society.

- Community healing: Prevent community trauma. Community trauma can result from experiencing violence and it can also increase the likelihood of violence, contributing to a mutually reinforcing cycle. Let’s support healing and resilience through strategies that rebuild social relationships and networks, reclaim and improve public spaces, promote community healing, and foster economic stability and prosperity. Prevention Institute’s Adverse Community Experiences and Resilience Framework , provides an approach for addressing and preventing community trauma.

- Mental health and wellbeing: Invest in communities to promote resilience and mental health and wellbeing. Mental illness is not at the root of our country’s high rate of gun violence, in fact, people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators. However, we know we can do more to foster mental health and wellbeing in the first place . Through our national initiative, Making Connections for Mental Health and Wellbeing Among Men and Boys , with communities across the US, we’re learning that there are pillars of wellbeing that promote wellbeing which is supportive of efforts to prevent multiple forms of violence, including belonging/connectedness, control of destiny, dignity, hope/aspiration, safety and trust. We are also seeing community members come together to change their community environments to promote mental health and wellbeing, including as a suicide prevention approach.

- Support healthy norms about masculinity: Explore the pathways between gun violence and harmful norms that have been about maintaining power and privilege. The majority of men do not perpetrate gun violence; however, the majority of people who use guns against others and themselves are boys and men. For instance, the majority of the mass shooters over decades have been men. How do expectations about masculinity in different cultural contexts that promote, domination, control, and risk-taking connect to distress, bias and discrimination, and gun violence perpetration? How do gaps in expectations of power and privilege versus reality play into this? Why does our dominant culture permit a destructive desire for power over others? Answering questions like these can glean important insights and help us move toward a culture of equitable safety.

- Impulsive anger: Explore the linkages between anger and gun violence. More research is needed to examine patterns of impulse control, empathy, problem solving, and anger management across shootings, as well as interactions of these functions with the harmful norms described in the previous recommendation. Through a public health approach, we want to understand who is at a greater risk for violence as a means to creating long-term solutions to stop the issue in the first place. Further analysis may provide answers regarding particular linkages and what to do when functions are compromised.

- Economic development: Reduce concentrated disadvantage and invest in employment opportunities. As Rev. Gregory Boyle has long said of his work in East Los Angeles, “Nothing stops a bullet like a job.” Lack of employment opportunities increases the risk for gun violence, and on the other hand, economic opportunity protects against violence. Promoting equitable access to education programs, job training, and employment programs with mentorship for residents of neighborhoods with concentrated disadvantage, especially young people can be effective in reducing gun violence. For example, a study of One Summer Chicago Plus , a jobs program designed to reduce violence and prepare youth from some of the city’s most violence neighborhoods for the labor market – saw a 43% drop in violent-crime arrests of participants. Further, neighborhood-based economic development strategies such as Business Improvement Districts that bring public and private partners together to invest in neighborhood services, activities, and improvements, have also been shown to reduce violence, including gun violence.

- Law enforcement violence: Establish accountability for sworn officers and private security. Ensure that police and security industries examine disparities regarding who they protect versus who is most often harmed as a result of their actions. With this information, these sectors should develop effective approaches to reduce harm in those populations, including unarmed African American men and people with mental illnesses. Current approaches being explored include implicit-bias training , problem-oriented policing , and restorative justice . Moving forward, it’s important to determine and understand the most effective strategies.

- Technology: Advance gun safety and self-defense technology. As the call for gun safety continues to increase, we must consider the role of new technologies . Just as cars continue to have new safety measures embedded in the technology, from fingerprint scanners to PIN codes and RFID chips, there are ongoing developments to increase the safety of guns and gun storage that require further analysis to assess effectiveness. In addition, technologies that are alternatives to guns are being developed to support self-protection to reduce the perceived need for a firearm for self-defense.

As our families, communities, and country reel from terrible daily tragedies, we must vow to change our culture and our policies and to stop this cycle of violence. We should be able to live in our homes, send our children to first grade, pray in our houses of worship, shop in our local malls, and walk through our streets and neighborhoods without being shot. Together we can take action in the memory of those who died and insist that this never happen again. Please take action and support changes like those outlined above to prevent gun violence.

Learn more about preventing gun violence from other organizations and resources we’ve found helpful:

American Journal of Public Health

American Public Health Association

American Psychological Association

Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence

Everytown for Gun Safety

Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence

Harvard T.H. School of Public Health

Hope and Heal Fund

Interdisciplinary Group on Preventing School and Community Violence call to action

International Firearm Injury Prevention and Policy

Movement towards Violence as a Health Issue

Pew Research Center Americans’ views on guns and gun ownership

RAND Corporation

Smart Tech Challenges Foundation

Smarter Crime Control: A Guide to a Safer Future for Citizens, Communities, and Politicians.

Speak for Safety campaign for Gun Violence Restraining Order

States for Gun Safety Coalition

The Joyce Foundation

University of California, Davis – Violence Prevention Program

Violence Policy Center

If you have additional resources we should add to the list, email [email protected] .

Supported by a grant from the Langeloth Foundation

Related Publications

Prevention institute summary of recommendations to prevent gun violence, prevention institute full recommendations for preventing gun violence.

Center for Gun Violence Solutions

- Make a Gift

- Stay Up-To-Date

- Research & Reports

- State-By-State Data

- Firearm Violence in the United States

- National Survey of Gun Policy

The Public Health Approach to Prevent Gun Violence

A public health approach to prevent gun violence brings together a range of experts across sectors—including researchers, advocates, legislators, community-based organizations, and others—in a common effort to develop, evaluate, and implement equitable, evidence-based solutions.

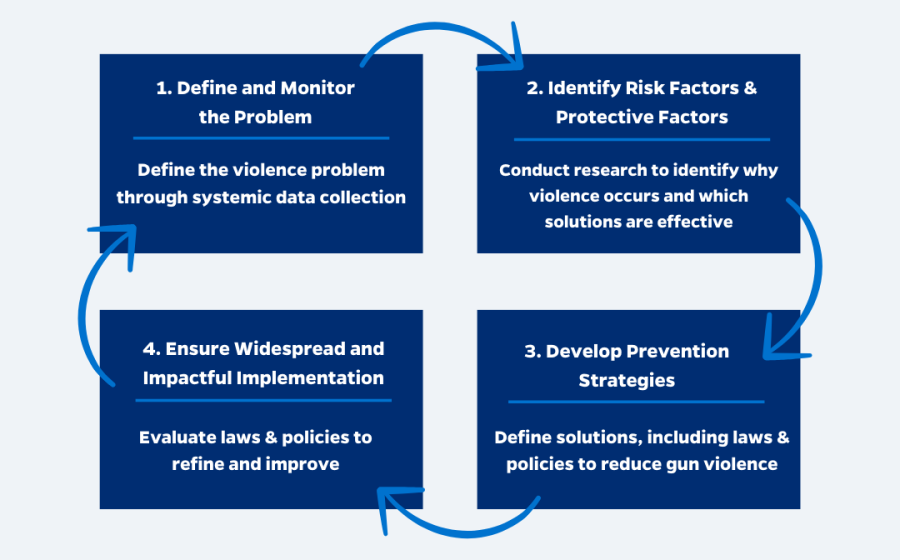

Public health is the science of reducing and preventing injury, disease, and death and promoting the health and well-being of populations through the use of data, research, and effective policies and practices. A public health approach to prevent gun violence is a population level approach that addresses both firearm access and the factors that contribute to and protect from gun violence. This approach brings together institutions and experts across disciplines in a common effort to: 1) define and monitor the problem, 2) identify risk and protective factors, 3) develop and test prevention strategies, and 4) ensure widespread adoption of effective strategies. By using a public health approach we can prevent gun violence in all its forms and strive towards health equity, where everyone can live free from gun violence.

Quick Facts About the Public Health Approach to Prevent Gun Violence:

Gun violence is a public health epidemic,.

resulting in nearly 45,000 deaths annually in recent years (2019-2021) and an estimated 76,000 nonfatal injuries. 1,2

The public health approach

addresses the many forms of gun violence by focusing both on firearm access and underlying risk factors that contribute to gun violence.

The public health approach is divided into four steps:

(1) define and monitor the problem,

(2) identify risk and protective factors,

(3) develop prevention strategies, and

(4) ensure widespread adoption of effective strategies.

The public health epidemic of gun violence is preventable.

We recommend evidence-based solutions to prevent gun death and injury in all of its forms. These solutions include, Firearm Purchaser Licensing, Extreme Risk Protection Orders and Domestic Violence Protection Orders, safe and secure gun storage, r egulating the public carry of firearms , and Community Violence Intervention.

On This Page

Each day more than 120 Americans die by firearms. 3 These deaths are preventable.

A comprehensive public health approach is needed to address the gun violence epidemic. This approach brings together a wide range of experts to determine the problem, identify key risk factors, develop evidence-based policies and programs, and ensure effective implementation and evaluation. Through a public health approach to gun violence, we can cure this epidemic, save thousands of lives, and make gun violence in America rare and abnormal.

What is Public Health?

Public health is the science of reducing and preventing injury, disease, and death and promoting the health and well-being of populations through the use of data, research, and effective policies and practices. Public health works to address the underlying causes of a disease or injury before they occur, promote healthy behaviors, and control the spread of outbreaks. Public health researchers and practitioners then work with communities and populations to implement and evaluate programs and policies that are based on research. Policymakers, researchers, and advocates have successfully used the public health approach in the United States to drastically decrease premature death rates, reduce injury, and improve the health and well-being of the population, including by eradicating diseases like polio, promoting widespread usage of vaccines, reducing smoking-related deaths, addressing environmental toxins, and decreasing motor vehicle crashes.

Why is Gun Violence a Public Health Epidemic?

Gun violence is a public health epidemic that affects the well-being and public safety of all Americans. In 2021, nearly 49,000 Americans were killed by gun violence, more than the number of Americans killed in car crashes. 4 An additional 76,000 Americans suffer nonfatal firearm injuries, and millions of Americans face the trauma of losing a loved one or living in fear of being shot. 5 The impacts of gun violence, both direct and indirect, inflict an enormous burden on American society. When a child is shot and killed, they lose decades of potential: the potential to grow up, have a family, contribute to society, and pursue their passions in life. When compared to other communicable and infectious diseases, gun violence often poses a larger burden on society in terms of potential years of life lost. In 2020, firearm deaths accounted for 1,131,105 years of potential life lost before the age of 65—more than diabetes, stroke, and liver disease combined. 6

Scope of Gun Violence

Americans are impacted by various forms of gun violence – including suicide, homicide, and unintentional deaths, as well as nonfatal gunshot injuries, threats, and exposure to gun violence in communities and society.

Firearm Suicide:

Each year, nearly 25,000 Americans die by firearm suicide. 7

Half of all suicide deaths are by firearm. 8

Suicide attempts by firearm are almost always deadly — 9 out of 10 firearm suicide attempts result in death. 9

Access to a firearm in the home increases the odds of suicide more than three-fold. 10

Firearm Homicide:

Each year 18,000 Americans die by firearm homicide. 11

Eight out of ten (79%) of homicides are committed with a firearm. 12

Access to firearms — such as the presence of a gun in the home — doubles the risk for homicide victimization. 13,14

The firearm homicide rate in the United States is 25.2 times higher than other industrialized countries. 15

Domestic Violence:

More than half of female intimate partner homicides are committed with a gun. 16

There are about 4.5 million women in America who have been threatened with a gun and nearly 1 million women who have been shot or shot at by an intimate partner. 17

A woman is five times more likely to be murdered when her abuser has access to a gun. 18

Police-Involved Shootings:

1,000 Americans are shot and killed by police every year. 19

Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by police-involved shootings and are killed at more than twice the rate as White Americans. 20

An estimated 800 of people are wounded by police shootings each year. 21

Unintentional Shootings:

Each year, more than 520 people die from unintentional firearm injuries — an average of one death every 17 hours. 22

More than 140 children and teens (0-19) die each year due to unintentional gun injuries. 23

Americans are four times more likely to die from an unintentional gun injury than people living in other high-income countries. 24

Mass Shootings:

Each year, there are an estimated 600 mass shootings with four or more people shot and/or killed in a single event — more than 500 people are killed and 2,000 are injured. 25

From 2019 to 2021, there were an average of 27 incidents annually where four or more people were killed at a single event —in total more than 130 people were killed. 26

From 2013 to 2022, the number of mass shootings (shootings where four or more people were shot and/or killed) have doubled; so too has the number of people killed and injured from the shootings. 27

States with more permissive gun laws and greater gun ownership had higher rates of mass shootings. 28

Nonfatal Firearm Injuries:

For every person in the United States who dies by firearm, two people are treated at hospitals for nonfatal gunshot wounds. 29

Each year there are over 76,000 nonfatal gunshot injuries, costing hospitals an estimated $2.8 billion annually. 30,31

Gun assaults and unintentional injuries make up the vast majority of nonfatal gun injuries; gun suicide attempts accounted for aproximetaly 5% of nonfatal gun injuries. 32

Exposure to Gun Violence:

More than half of all adults in the U.S. report that they, or a family member have been involved in a gun violence-related incident. 33

One in five adults say they have had a family member killed by a gun.

One in five adults report being personally threated or intimated with a gun. 34

One-third of US adults report that fear of a mass shooting has prevented them from attending certain places or events. 35

How Public Health Differs from Healthcare

People often assume that public health is the same as healthcare. While both strive to improve health and well-being, they approach this goal differently. In healthcare, the focus is on improving the health of the individual. In contrast, public health focuses on improving the health of an entire population through large-scale interventions and prevention programs.

Public health works to address the many factors that determine the health and well-being of populations. These factors are often referred to as risk and protective factors. They are characteristics or behaviors in individuals, families, communities, and the larger society that increase or decrease the likelihood of premature death, injury, or poor health.

What is the Public Health Approach?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization outline a public health approach to violence prevention based on four steps: (1) define and monitor the problem, (2) identify risk and protective factors, (3) develop and test prevention strategies, (4) ensure widespread adoption of effective strategies. 36,37

Researchers and policymakers need reliable data to understand the scope and complexity of gun violence. There are many different types of gun violence, and each type often requires different prevention strategies. Collecting and distributing reliable firearm data is essential to combating gun violence through a public health approach. Gun violence prevention researchers need reliable and timely data around the number of firearm fatalities and nonfatal injuries that occur in the United States each year. This data should include the demographics of the victim and shooter (if applicable), the location and time of the shooting, and the type of gun violence that occurred. Databases should classify the types of gun violence (suicides, intimate partner violence, mass shootings, interpersonal violence, police shootings, unintentional injuries) based on clearly defined and standardized definitions. This data should be made widely available and easily accessible to the general public free of charge.

The public health approach focuses on prevention and addresses population level risk factors that lead to gun violence and protective factors that reduce gun violence. A thorough body of research has identified specific risk factors, both at the individual level and at the community and societal level, which increase the likelihood of engaging in gun violence. At an individual level, having access to guns is a risk factor for violence, increasing the likelihood that a dangerous situation will become fatal. Simply having a gun in one's home doubles the chance of dying by homicide and increases the likelihood of suicide death by over three-fold. 38 Other individual risk factors closely linked to gun violence include: a history of violent behavior, exposure to violence, and risky alcohol and drug use. 39,40 Community level factors also increase the likelihood of gun violence. Under-resourced neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty, lack of economic opportunity, and social mobility are more likely to experience high rates of violence. These community level factors are often the result of deep structural inequities rooted in racism. 41,42 Policies and programs should mitigate risk factors and promote protective factors at the individual and community levels.

Policymakers and practitioners must craft interventions which address the risk factors for gun violence. These interventions should be routinely tested to ensure they are effective and equitable; rigorous evaluations should be conducted on a routine basis. The foundation for effective gun violence prevention policy is a universal background check law, ensuring that each person who seeks to purchase or transfer a firearm undergoes a background check prior to purchase. Universal background checks should be supplemented by a firearm purchaser licensing system, which regulates and tracks the flow of firearms, to ensure that firearms do not make it into the hands of prohibited individuals. Building upon this, policymakers can create interventions which target behavioral risk-factors for gun violence (e.g. extreme risk laws, DVPO) and they can push for policies which address community risk factors that lead to violence (e.g. investing in community based violence prevention programs). In addition to these gun violence prevention policies, there are a number of evidence-based strategies that can reduce gun violence within communities. For example, community based violence intervention programs work to de-escalate conflicts, interrupt cycles of retaliatory violence, and support those at elevated risk for violence.

While it is essential to pass strong laws, it is equally important to enforce and implement these laws and to scale up evidence-based programs. Strong gun violence prevention policies are only effective if they are properly implemented and enforced in an equitable manner. A key focus of the public health approach is ensuring that these strategies are not only effective but that they also promote equity. Historically disenfranchised groups should be involved in the implementation process to ensure that public health strategies do not have unintended consequences. For example, gun violence prevention policies should be consistently evaluated to ensure that they do not stigmatize individuals living with mental illness or perpetuate the discriminatory and racist practices embedded in the criminal justice system. The public health approach includes a focus on allocating funds for implementation and evaluation of these gun violence prevention strategies at the federal, state, and local level. Funds should be allocated to train the proper stakeholders to ensure that new policies and programs are properly adopted and achieve measurable and equitable outcomes.

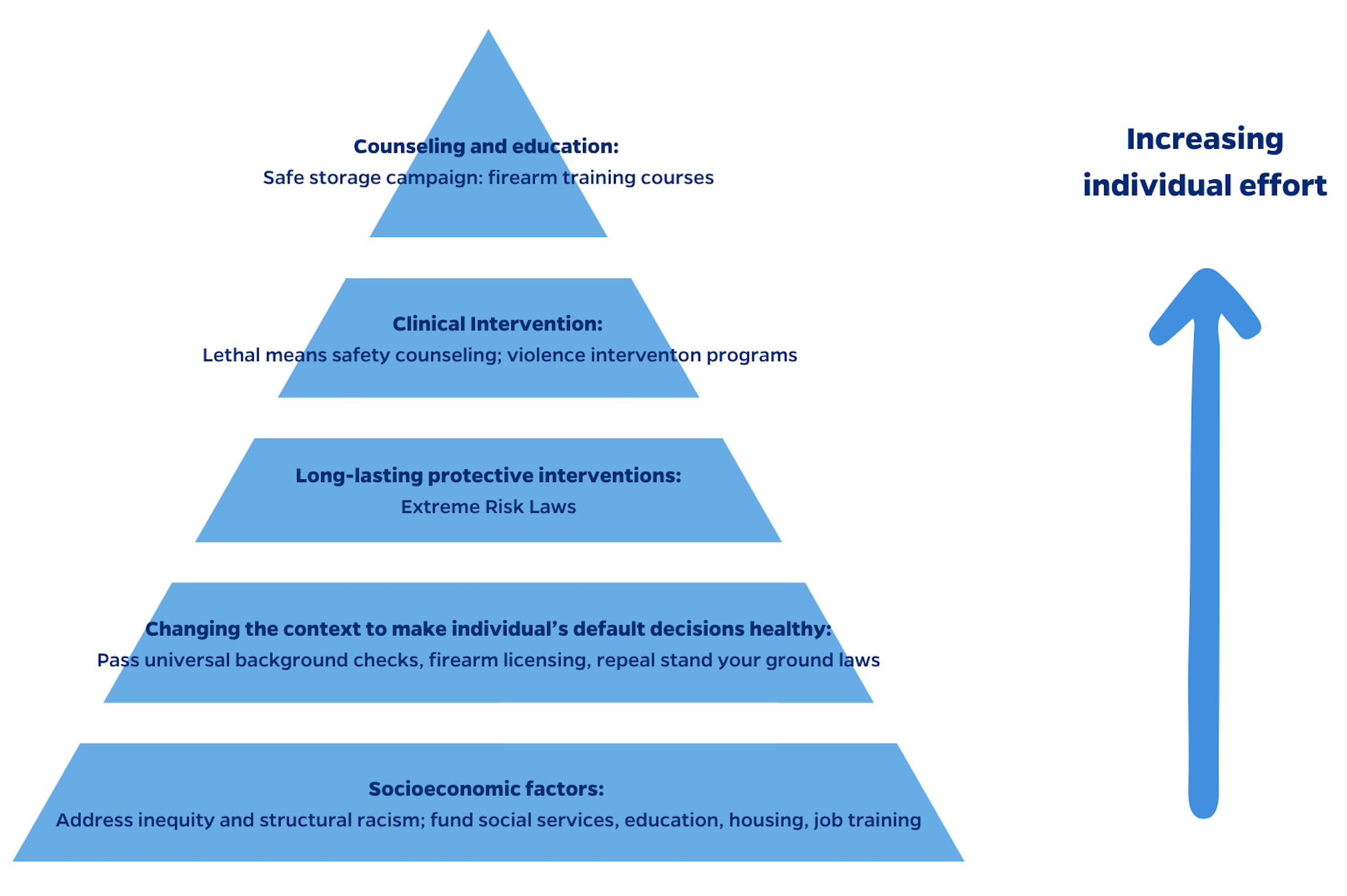

Health Impact Pyramid

The goal of public health is to maximize the overall health and well-being of populations. Public health practitioners do this by developing a wide-range of interventions. These interventions address risk and protective factors ranging from factors at the individual level to the societal level. The public health pyramid helps researchers conceptualize the many different levels of intervention needed to address a public health problem like gun violence. 43

At the top of the pyramid are narrowly tailored interventions that work with individuals at risk for gun violence. These interventions, like lethal means safety counseling and violence intervention programs, can have tremendous impact in reducing gun violence. Yet, they also require individual action. These programs provide the tools and support to change behavior, but the individuals themselves must be willing to take action and change behavior.

The middle of the pyramid includes interventions that require less individual action. They are often laws and policies that change the environments within communities to mitigate risk factors. One such policy is universal background checks and firearm purchaser licensing. Research shows that when individuals are required to undergo a background check and obtain a license to purchase a firearm, far fewer firearms are diverted into illegal markets and used to perpetrate violence.

At the bottom of the public health pyramid are the conditions within society that lead to poor health outcomes like gun violence. These factors are often referred to as the root causes or social determinants of health. Socioeconomic factors, such as racial disparities, inequality, poverty, inadequate housing and education, are all risk factors for interpersonal gun violence. Policies that address these root causes have enormous potential to reduce gun violence and improve health. These policies, while requiring a broad collective effort to achieve, require minimal individual effort to be effective at reducing gun violence.

How Do We Address Gun Violence Through the Public Health Approach?

The public health approach is multifaceted and comprehensive and brings together institutions and experts across disciplines in a common effort to develop a variety of evidence-based interventions. 45 This comprehensive approach to tackling public health crises in America has been used over the last century to eradicate diseases like polio, reduce smoking deaths, and make cars safer. This public health approach has saved millions of lives. We can learn from the public health successes -- like car safety -- and apply these lessons to preventing gun violence.

Applying the public health successes of car safety to prevent gun violence

One of the greatest American public health successes is our nation’s work to make cars safer.

By using a comprehensive public health approach to car safety, the United States reduced per-mile driving deaths by nearly 80% from 1967 to 2017. 46 This public health approach to car safety prevented more than 3.5 million deaths over these fifty years. 47 In the years since 2017 car crashes have begun to increase. This recent increase illustrates how threats to public health constantly evolve, and the work of public health practitioners is never complete. They must continue to monitor the problem, identify emerging risks, and develop new solutions. While the work in U.S. auto safety is far from complete, the comparisons illustrates the steps needed to address the epidemic of gun violence. To reduce gun violence, we should apply this same time-tested public health approach.

Sources: National Traffic Highway Safety Administration (NTHSA). Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities and Fatality Rates, 1899-2017; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1968-2017 on CDC WONDER Online Database.

Applying the Public Health Successes of Auto Safety to Gun Violence Prevention

Recommendations.

Apply the public health approach for effective gun violence prevention.

Public health is the science of reducing and preventing injury, disease, and death and promoting the health and well-being of populations through the use of data, research, and effective policies and practices. The public health approach has been successfully applied to tackle a wide variety of complex health problems at the population level. Gun violence is a public health epidemic that requires a public health solution. We recommend the following:

Better Data Collection

Federal, state, and local governments should collect more comprehensive gun violence data for fatal and non-fatal firearm injuries, shootings that may not involve physical injuries, and firearm-involved crimes where no shots were fired, including domestic violence-related threats. Federal, state, and local governments should make data publicly available where possible and particularly to researchers studying gun violence and its prevention.

Research Funding

Enhanced research funding is key for advancing knowledge and improving public health interventions and outcomes. Federal, state, and local governments, in addition to foundations and universities, should dedicate funding to research gun violence prevention.

Evidence-based Policies and Practices

Gun violence is a muliticated problem that takes many forms and requires a multitude of data-driven solutions. Gun violence prevention policies and practices should be evidence-based.

- Firearm Purchaser Licensing or permit-to-purchase laws require all prospective gun purchasers to obtain license prior to buying a gun from a dealer or a private seller. These laws enhance universal background checks by establishing a licensing application process as well as considering additional components such as fingerpinting, a more through vetting process, and a built-in waiting period to prevent individuals with a history of violence, those at risk for future interpersonal violence or suicide, and gun traffickers from obtaining firearms.

- Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO) is a civil process allowing law enforcement, family members, and, in some states, medical professionals and other parties to petition a court to temporarily restrict access to guns from individuals determined to be at elevated risk of harming themselves or others. ERPO laws are associated with lower rates of firearm suicide and have been successfully used in mass shooting threats. 48

- Community Violence Intervention (CVI) programs aim to identify and support the small number of people at risk for violence by providing them with wraparound mental health and social supports. Investing in CVI programs provides a public health approach to gun violence prevention, interrupting cycles of violence, and addressing the unique needs of the community where systemic racism, disinvestment, and trauma occur.

- Safe and secure gun storage practices, such as Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws, require households with a child or teen to keep firearms unloaded and locked when unattended. These practices promote responsible firearm storage practices protecting children and teenagers from various forms of gun violence, including unintentional shootings and gun suicides. CAP laws are linked to sizable reductions in child and teen gun deaths, including reductions in youth suicide, accidental shootings, and homicides. 49,50

- Public carry of firearms poses a serious threat to safety. Permissive public carry and “stand your ground” laws increase violence by allowing people with violent histories to carry their firearms in public, providing more opportunities for armed intimidation and shootings in response to hostile interactions, and increasing criminals’ access to guns. States should regulate the carrying of guns in public by prohibiting open carry of firearms particularly in sensitive places, passing strong concealed carry permitting laws, and repealing “stand your ground” laws.

Implementation and Evaluation

It is essential to pass evidence-based policies that address gun violence, but that is not enough. Gun violence takes many forms and impacts a variety of groups, requiring ongoing surveillance and evaluation to ensure effective implementation of policies and practices. Federal, state, and local governments should dedicate resources to ensure proper implementation, education and ongoing evaluation of gun violence prevention policies.

1 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

2 Song Z, Zubizarreta JR, & Giuriato M. (2022). Changes in health care spending, use, and clinical outcomes after nonfatal firearm injuries among survivors and family members. Annals of Internal Medicine . https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-2812

3 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

4 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

5 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health . https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

6 National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. WISQARS Years of Potential Life Lost (YPLL) Report. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

7 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

8 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

9 Conner A, Azrael D, & Miller M. (2019). Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A nationwide population-based study. Annals of Internal Medicine .

10 Anglemyer A, Horvath T, & Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine .

11 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

12 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

13 Anglemyer A, Horvath T, & Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Annals of Internal Medicine .

14 Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, & Kresnow MJ. (2004). Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study . American Journal of Epidemiology .

15 Choron R, Spitzer S, & Sakran JV. (2019). Firearm violence in America: is there a solution? Advances in Surgery.

16 Zeoli AM, Malinski R, & Turchan B. (2016). Risks and targeted interventions: Firearms in intimate partner violence . Epidemiologic Reviews .

17 Sorenson SB, & Schut RA. (2018). Nonfatal Gun Use in Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review of the Literature . Trauma, Violence, & Abuse .

18 Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, Block C, Campbell D, Curry MA… & Laughon K. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study . American Journal of Public Health.

19 Fatal Force database . (2020). Washington Post .

20 Fatal Force database . (2020). Washington Post .

21 Average annual nonfatal shootings by police, 2018-2020. Ward, J. A. (2023). Beyond Urban Fatalities: An Analysis of Shootings by Police in the United States (Doctoral dissertation, Johns Hopkins University).

22 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

23 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death. Available: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html.

24 Solnick SJ, & Hemenway D. (2019). Unintentional firearm deaths in the United States 2005–2015 . Injury Epidemiology.

25 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Gun Violence Archive. (2023). Available: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/ .

26 Three-year average, 2019-2021. Gun Violence Archive. (2023). Available: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/ .

27 Gun Violence Archive. (2023). Available: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/ .

28 Reeping PM, Cerda M, Kalesan B, Wiebe DJ, Galea S, & Branas CC. (2019). State gun laws, gun ownership, and mass shootings in the US: Cross sectional time series. BMJ Journal . https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l542

29 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health . https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

30 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health . https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

31 Avraham JB, Frangos SG, & DiMaggio CJ. (2018). The epidemiology of firearm injuries managed in US emergency departments . Injury Epidemiology.

32 Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health . https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925

33 One in Five Adults Say They’ve Had a Family Member Killed by a Gun, Including Suicide, and One in Six Have Witnessed a Shooting; Among Black Adults, a Third Have Experienced Each. (2023). KFF. Available: https://www.kff.org/other/press-release/one-in-five-adults-say-theyve-had-a-family-member-killed-by-a-gun-including-suicide-and-one-in-six-have-witnessed-a-shooting-among-black-adults-a-third-have-experienced-each/

34 One in Five Adults Say They’ve Had a Family Member Killed by a Gun, Including Suicide, and One in Six Have Witnessed a Shooting; Among Black Adults, a Third Have Experienced Each. (2023). KFF. Available: https://www.kff.org/other/press-release/one-in-five-adults-say-theyve-had-a-family-member-killed-by-a-gun-including-suicide-and-one-in-six-have-witnessed-a-shooting-among-black-adults-a-third-have-experienced-each/

35 One-third of US Adults say fear of mass shootings prevents them from going to certain places or events. (2019) American Psychological Association. Press Release. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2019/08/fear-mass-shooting

36 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention.

37 World Health Organization. Violence Prevention Alliance. The Public Health Approach .

38 Anglemyer A, Horvath T, & Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Annals of Internal Medicine .

39 Consortium for Risk‐Based Firearm Policy. (2013). Guns, public health, and mental illness: An evidence-based approach for state policy .

40 Consortium for Risk‐Based Firearm Policy. (20 23). Alcohol Misuse and Gun Violence: An Evidence-Based Approach for State Policy. Available: https://riskbasedfirearmpolicy.org/reports/alcohol-misuse-and-gun-violence-an-evidence-based-approach-for-state-policy/

41 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Risk and Protective Factors .

42 Sampson RJ. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press.

43 Frieden TR. (2010). A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. American journal of public health.

44 Frieden, TR. (2010). A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health . https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652

45 Hemenway D, & Miller M. (2013). Public health approach to the prevention of gun violence . New England Journal of Medicine.

46 Traffic Safety Facts: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data. (2020). Annual Report Tables . National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Available:

47 On 50th anniversary of ralph nader’s ‘unsafe at any speed,’ safety group reports auto safety regulation has saved 3.5 million lives. (2015). The Nation.

48 Research on Extreme Risk Protection Orders: An Evidence-Based Policy That Saves Lives. (2023). Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Available: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2023-02/research-on-extreme-risk-protection-orders.pdf

49 Azad HA, Monuteaux MC, Rees CA, Siegel M, Mannix R, Lee LK, Sheehan KM, & Fleegler EW. (2020). Child Access Prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 Years, 1991-2016. JAMA Pediatrics. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2761305

50 Webster DW, Vernick JS, Zeoli AM, & Manganello JA. (2004). Association between youth-focused firearm laws and youth suicides. Jama Network. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/199194

Support Our Life Saving Work

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Case Discussions

- Special Symposiums

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with Public Health Ethics?

- About Public Health Ethics

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, the burden of firearm violence, understanding and reducing firearm violence is complex and multi-factorial, interventions and recommendations, conclusions, research ethics.

- < Previous

Firearm Violence in the United States: An Issue of the Highest Moral Order

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Chisom N Iwundu, Mary E Homan, Ami R Moore, Pierce Randall, Sajeevika S Daundasekara, Daphne C Hernandez, Firearm Violence in the United States: An Issue of the Highest Moral Order, Public Health Ethics , Volume 15, Issue 3, November 2022, Pages 301–315, https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phac017

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Firearm violence in the United States produces over 36,000 deaths and 74,000 sustained firearm-related injuries yearly. The paper describes the burden of firearm violence with emphasis on the disproportionate burden on children, racial/ethnic minorities, women and the healthcare system. Second, this paper identifies factors that could mitigate the burden of firearm violence by applying a blend of key ethical theories to support population level interventions and recommendations that may restrict individual rights. Such recommendations can further support targeted research to inform and implement interventions, policies and laws related to firearm access and use, in order to significantly reduce the burden of firearm violence on individuals, health care systems, vulnerable populations and society-at-large. By incorporating a blended public health ethics to address firearm violence, we propose a balance between societal obligations and individual rights and privileges.

Firearm violence poses a pervasive public health burden in the United States. Firearm violence is the third leading cause of injury related deaths, and accounts for over 36,000 deaths and 74,000 firearm-related injuries each year ( Siegel et al. , 2013 ; Resnick et al. , 2017 ; Hargarten et al. , 2018 ). In the past decade, over 300,000 deaths have occurred from the use of firearms in the United States, surpassing rates reported in other industrialized nations ( Iroku-Malize and Grissom, 2019 ). For example, the United Kingdom with a population of 56 million reports about 50–60 deaths per year attributable to firearm violence, whereas the United States with a much larger population, reports more than 160 times as many firearm-related deaths ( Weller, 2018 ).

Given the pervasiveness of firearm violence, and subsequent long-term effects such as trauma, expensive treatment and other burdens to the community ( Lowe and Galea, 2017 ; Hammaker et al. , 2017 ; Jehan et al. , 2018 ), this paper seeks to examine how various evidence-based recommendations might be applied to curb firearm violence, and substantiate those recommendations using a blend of the three major ethics theories which include—rights based theories, consequentialism and common good. To be clear, ours is not a morally neutral paper wherein we weigh the merits of an ethical argument for or against a recommendation nor is it a meta-analysis of the pros and cons to each public health recommendation. We intend to promote evidence-based interventions that are ethically justifiable in the quest to ameliorate firearm violence.

It is estimated that private gun ownership in the United States is 30% and an additional 11% of Americans lived with someone who owed a gun in 2017 ( Gramlich and Schaeffer, 2019 ). Some of the reported motivations for carrying a firearm include protection against people (anticipating future victimization or past victimization experience) and hunting or sport shooting ( Schleimer et al. , 2019 ). A vast majority of firearm-related injuries and death occur from intentional harm (62% from suicides and 35% from homicides) versus 2% of firearm-related injuries and death occurring from unintentional harm or accidents (e.g. unsafe storage) ( Fowler et al. , 2015 ; Lewiecki and Miller, 2013 ; Monuteaux et al. , 2019 ; Swanson et al. , 2015 ).

Rural and urban differences have been noted regarding firearms and its related injuries and deaths. In one study, similar amount of firearm deaths were reported in urban and rural areas ( Herrin et al. , 2018 ). However, the difference was that firearm deaths from homicides were higher in urban areas, and deaths from suicide and unintentional deaths were higher in rural areas ( Herrin et al. , 2018 ). In another study, suicides accounted for about 70% of firearm deaths in both rural and urban areas ( Dresang, 2001 ). Hence, efforts to implement these recommendations have the potential to prevent most firearm deaths in both rural and urban areas.

The burden of firearm injuries on society consists of not only the human and economic costs, but also productivity loss, pain and suffering. Firearm-related injuries affect the health and welfare of all and lead to substantial burden to the healthcare industry and to individuals and families ( Corso et al. , 2006 ; Tasigiorgos et al. , 2015 ). Additionally, there are disparities in firearm injuries, whereby firearm injuries disproportionately affect young people, males and non-White Americans ( Peek-Asa et al. , 2017 ). The burden of firearm also affects the healthcare system, racial/ethnic minorities, women and children.

Burden on Healthcare System

Firearm-related fatalities and injuries are a serious public health problem. On average more than 38 lives were lost every day to gun related violence in 2018 ( The Education Fund to Stop Gun Violence (EFSGV), 2020 ). A significant proportion of Americans suffer from firearm non-fatal injuries that require hospitalization and lead to physical disabilities, mental health challenges such as post-traumatic stress disorder, in addition to substantial healthcare costs ( Rattan et al. , 2018 ). Firearm violence and related injuries cost the U.S. economy about $70 billion annually, exerting a major effect on the health care system ( Tasigiorgos et al. , 2015 ).

Victims of firearm violence are also likely to need medical attention requiring high cost of care and insurance payouts which in turn raises the cost of care for everyone else, and unavoidably becomes a financial liability and source of stress on the society ( Hammaker et al. , 2017 ). Firearm injuries also exert taxing burden on the emergency departments, especially those in big cities. Patients with firearm injuries who came to the emergency departments tend to be overwhelmingly male and younger (20–24 years old) and were injured in an assault or unintentionally ( Gani et al. , 2017 ). Also, Carter et al. , 2015 found that high-risk youth (14–24 years old) who present in urban emergency departments have higher odds of having firearm-related injuries. In fact, estimates for firearm-related hospital admission costs are exorbitant. In 2012, hospital admissions for firearm injuries varied from a low average cost of $16,975 for an unintentional firearm injury to a high average cost of $32,237 for an injury from an assault weapon ( Peek-Asa et al. , 2017 ) compared with an average cost of $10,400 for a general hospital admission ( Moore et al. , 2014 ).

Burden on Racial/Ethnic Minorities, Women and Children

Though firearm violence affects all individuals, racial disparities exist in death and injury and certain groups bear a disproportionate burden of its effects. While 77% of firearm-related deaths among whites are suicides, 82% of firearm-related deaths among blacks are homicides ( Reeves and Holmes, 2015 ). Among black men aged 15–34, firearm-related death was the leading cause of death in 2012 ( Cerdá, 2016 ). The racial disparity in the leading cause of firearm-related homicide among 20- to 29-year-old adults is observed among blacks, followed by Hispanics, then whites. Also, victims of firearms tend to be from lower socioeconomic status ( Reeves and Holmes, 2015 ). Understanding behaviors that underlie violence among young adults is important. Equally important is the fiduciary duty of public health officials in creating public health interventions and policies that would effectively decrease the burden of gun violence among all Americans regardless of social, economic and racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Another population group that bears a significant burden of firearm violence are women. The violence occurs in domestic conflicts ( Sorenson and Vittes, 2003 ; Tjaden et al. , 2000 ). Studies have shown that intimate partner violence is associated with an increased risk of homicide, with firearms as the most commonly used weapon ( Leuenberger et al. , 2021 ; Gollub and Gardner, 2019 ). However, firearm threats among women who experience domestic violence has been understudied ( Sullivan and Weiss, 2017 ; Sorenson, 2017 ). It is estimated that nearly two-thirds of women who experience intimate partner violence and live in households with firearms have been held at gunpoint by intimate partners ( Sorenson and Wiebe, 2004 ). Firearms are used to threaten, coerce and intimidate women. Also, the presence of firearms in a home increases the risk of women being murdered ( Campbell et al. , 2015 ; Bailey et al. , 1997 ). Further, having a firearm in the home is strongly associated with more severe abuse among pregnant women in a study by McFarlane et al. (1998) . About half of female intimate partner homicides are committed with firearms ( Fowler, 2018 ; Díez et al. , 2017 ). Some researchers reported that availability of firearms in areas with fewer firearms restrictions has led to higher intimate partner homicides ( Gollub and Gardner, 2019 ; Díez et al. , 2017 ).

In the United States, children are nine times more likely to die from a firearm than in most other industrialized nations ( Krueger and Mehta, 2015 ). Children here include all individuals under age 18. These statistics highlight the magnitude of firearm injuries as well as firearms as a serious pediatric concern, hence, calls for appropriate interventions to address this issue. Unfortunately, children and adolescents have a substantial level of access to firearms in their homes which contributes to firearm violence and its related injuries ( Johnson et al. , 2004 ; Kim, 2018 ). About half of all U.S. households are believed to have a firearm, making firearms one of the most pervasive products consumed in the United States ( Violano et al. , 2018 ). Consequently, most of the firearms used by children and youth to inflict harm including suicides are obtained in the home ( Johnson et al. , 2008 ). Beyond physical harm, children experience increased stress, fear and anxiety from direct or indirect exposure to firearms and its related injuries. These effects have also been reported as predictors of post-traumatic stress disorders in children and could have long-term consequences that persist from childhood to adulthood ( Holly et al. , 2019 ). Additionally, the American Psychological Association’s study on violence in the media showed that witnessing violence leads to fear and mistrust of others, less sensitivity to pain experienced by others, and increases the tendency of committing violent acts ( Branas et al. , 2009 ; Calvert et al. , 2017 ).

As evidenced from the previous sections, firearm violence is a complex issue. Some argue that poor mental health, violent video games, substance abuse, poverty, a history of violence and access to firearms are some of the reasons for firearm violence ( Iroku-Malize and Grissom, 2019 ). However, the prevalence and incidence of firearm violence supersedes discrete issues and demonstrates a complex interplay among a variety of factors. Therefore, a broader public health analysis to better understand, address and reduce firearm violence is warranted. Some important factors as listed above should be taken into consideration to more fully understand firearm violence which can consequently facilitate processes for mitigation of the frequency and severity of firearm violence.

Lack of Research Prevents Better Understanding of Problem of Firearm Violence

A major stumbling block to understanding the prevalence and incidence of firearm related violence exists from a lack of rigorous scientific study of the problem. Firearm violence research constitutes less than 0.09% of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual budget ( Rajan et al. , 2018 ). Further research on firearm violence is greatly limited by the Dickey Amendment, first passed in 1996 and annually thereafter in budget appropriations, which prohibits use of federal funds to advocate or promote firearm control ( Rostron, 2018 ). As such, the Dickey Amendment impedes future federally funded research, even as public health’s interest in firearm violence prevention increased ( Peetz and Haider, 2018 ; Rostron, 2018 ). In the absence of rigorous research, a deeper understanding and development of evidence-based prevention measures continue to be needed.

Lack of a Public Health Ethical Argument Against Firearm Use Impedes Violence Prevention

We make an argument that gun violence is a public health problem. While some might think that public health is primarily about reducing health-related externalities, it is embedded in key values such as harm reduction, social justice, prevention and protection of health and social justice and equity ( Institute of Medicine, 2003 ). Public health practice is also historically intertwined with politics, power and governance, especially with the influence of the states decision-making and policies on its citizens ( Lee and Zarowsky, 2015 ). According to the World Health Organization, health is a complete physical, mental and social well-being that is not just the absence of injury or disease ( Callahan, 1973 ). Health is fundamental for human flourishing and there is a need for public health systems to protect health and prevent injuries for individuals and communities. Public health ethics, then, is the practical decision making that supports public health’s mandate to promote health and prevent disease, disability and injury in the population. It is imperative for the public health community to ask what ought to be done/can be done to curtail firearm violence and its related burdens. Sound public health ethical reasoning must be employed to support recommendations that can be used to justify various public policy interventions.

The argument that firearm violence is a public health problem could suggest that public health methods (e.g. epidemiological methods) can be used to study gun violence. Epidemiological approaches to gun violence could be applied to study its frequency, pattern, distribution, determinants and measure the effects of interventions. Public health is also an interdisciplinary field often drawing on knowledge and input from social sciences, humanities, etc. Gun violence could be viewed as a crime-related problem rather than public health; however, there are, of course, a lot of ways to study crime, and in this case with public health relevance. One dominant paradigm in criminology is the economic model which often uses natural experiments to isolate causal mechanisms. For example, it might matter whether more stringent background checks reduce the availability of guns for crime, or whether, instead, communities that implement more stringent background checks also tend to have lower rates of gun ownership to begin with, and stronger norms against gun availability. Therefore, public health authorities and criminologists may tend to have overlapping areas of expertise aimed to lead to best practices advice for gun control.

Our paper draws on three major theories: (1) rights-based theories, (2) consequentialism and (3) the common good approach. These theories make a convergent case for firearm violence, and despite their significant divergence, strengthen our public health ethics approach to firearm. The key aspects of these three theories are briefly reviewed with respect to how one might use a theory to justify an intervention or recommendation to reduce firearm injuries.

Rights-Based Theories

The basic idea of the rights framework is that people have certain rights, and that therefore it is impermissible to treat people in certain ways even if doing so would promote the overall good. People have rights to safety, security and an environment generally free from risky pitfalls. Conversely, people also have a right to own a gun especially as emphasized in the U.S.’s second amendment. Another theory embedded within our discussion of rights-based theories is deontology. Deontological approaches to ethics hold that we have moral obligations or duties that are not reducible to the need to promote some end (such as happiness or lives saved). These duties are generally thought to specify what we owe to others as persons ( rights bearers ). There are specific considerations that define moral behaviors and specific ways in which people within different disciplines ought to behave to effectively achieve their goals.

Huemer (2003) argued that the right to own a firearm has both a fundamental (independent of other rights) and derivative justification, insofar as the right is derived from another right - the right to self-defense ( Huemer, 2003 ). Huemer gives two arguments for why we have a right to own a gun:

People place lots of importance on owning a gun. Generally, the state should not restrict things that people enjoy unless doing so imposes substantial risk of harm to others.

People have a right to defend themselves from violent attackers. This entails that they have a right to obtain the means necessary to defend themselves. In a modern society, a gun is a necessary means to defend oneself from a violent attacker. Therefore, people have a right to obtain a gun.

Huemer’s first argument could be explained that it would be permissible to violate someone’s right to own or use a firearm in order to promote some impersonal good (e.g. number of lives saved). Huemer’s second argument also justifies a fundamental right to gun ownership. According to Huemer, gun restrictions violate the right of individual gun owners to defend themselves. Gun control laws will result in coercively stopping people to defend themselves when attacked. To him, the right to self-defense does seem like it would be fundamental. It seems intuitive to argue that, at some level, if someone else attacks a person out of the blue, the person is morally required to defend themselves if they cannot escape. However, having a right to self-defense does not entail that your right to obtain the means necessary to that thing cannot be burdened at all.

While we have a right to own a gun, that right is weaker than other kinds of rights. For example, gun ownership seems in no way tied to citizenship in a democracy or being a member of the community. Also, since other nations/democracies get along fine without a gun illustrates that gun ownership is not important enough to be a fundamental right. Interestingly, the UK enshrines a basic right to self-defense, but explicitly denies any right to possess any particular means of self-defense. This leads to some interesting legal peculiarities where it can be illegal to possess a handgun, but not illegal to use a handgun against an assailant in self-defense.

In the United States, implementing gun control policies to minimize gun related violence triggers the argument that such policies are infringements on the Second Amendment, which states that the rights to bear arms shall not be infringed. The constitution might include a right to gun ownership for a variety of reasons. However, it is not clear from the text itself that the right to bear arms is supposed to be as fundamental as the right to freedom of expression. Further, one could argue, then, that any form of gun regulation is borne from the rationale to retain our autonomy. Protections from gun violence are required to treat others as autonomous agents or as bearers of dignity. We owe others certain protections and affordances at least in part because these are necessary to respect their autonomy (or dignity, etc.). We discuss potential recommendations to minimize gun violence while protecting the rights of individuals to purchase a firearm if they meet the necessary and reasonable regulatory requirements. Most of the gun control regulations discussed in this article could provide an opportunity to ensure the safety of communities without unduly infringing on the right to keep a firearm.

Consequentialism

Consequentialism is the view that we should promote the common good even if doing so infringes upon some people’s (apparent) rights. The case for gun regulation under this theory is made by showing how many lives it would save. Utilitarianism, a part of consequentialist approach proposes actions which maximize happiness and the well-being for the majority while minimizing harm. Utilitarianism is based on the idea that a consequence should be of maximum benefit ( Holland, 2014 ) and that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness as the ultimate moral norm. If one believes that the moral purpose of public health is to make decisions that will produce maximal benefits for most affected, remove or prevent harm and ensure equitable distribution of burdens and benefits ( Bernheim and Childress, 2013 ), they are engaging in a utilitarian theory. Rights, including the rights to bear arms, are protected so long as they preserve the greater good. However, such rights can be overridden or ignored when they conflict with the principle of utility; that is to say, if greater harm comes from personal possession of a firearm, utilitarianism is often the ethical theory of choice to restrict access to firearms, including interventions that slow down access to firearms such as requiring a gun locker at home. However, it is important to note that utilitarians might also argue that one has to weigh how frustrating a gun locker would be to people who like to go recreationally hunting. Or how much it would diminish the feeling of security for someone who knows that if a burglar breaks in, it might take several minutes to fumble while inputting the combination on their locker to access their gun.

Using a utilitarian approach, current social statistics show that firearm violence affects a great number of people, and firearm-related fatalities and injuries threaten the utility, or functioning of another. Therefore, certain restrictions or prohibitions on firearms can be ethically justifiable to prevent harm to others using a utilitarian approach. Similarly, the infringement of individual freedom could be warranted as it protects others from serious harm. However, one might argue that a major flaw in the utilitarian argument is that it fails to see the benefit of self-defense as a reasonable benefit. Utilitarianism as a moral theory would weigh the benefits of proposed restrictions against its costs, including its possible costs to a felt sense of security on the part of gun owners. A utilitarian argument that neglects some of the costs of regulations wouldn’t be a very good argument.