U.S. Constitution.net

Federalist papers and the constitution.

During the late 1780s, the United States faced significant challenges with its initial governing framework, the Articles of Confederation. These issues prompted the creation of the Federalist Papers, a series of essays aimed at advocating for a stronger central government under the newly proposed Constitution. This article will examine the purpose, key arguments, and lasting impact of these influential writings.

Background and Purpose of the Federalist Papers

The Articles of Confederation, though a pioneer effort, left Congress without the power to tax or regulate interstate commerce, making it difficult to pay off Revolutionary War debts and curb internal squabbles among states.

In May 1787, America's brightest political minds convened in Philadelphia and created the Constitution—a document establishing a robust central government with legislative, executive, and judicial branches. However, before it could take effect, the Constitution needed ratification from nine of the thirteen states, facing opposition from critics known as Anti-Federalists.

The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay under the pseudonym "Publius," aimed to calm fears and win support for the Constitution. Hamilton initiated the project, recruiting Madison and Jay to contribute. Madison drafted substantial portions of the Constitution and provided detailed defenses, while Jay, despite health issues, also contributed essays.

The Federalist Papers systematically dismantled the opposition's arguments and explained the Constitution's provisions in detail. They gained national attention, were reprinted in newspapers across the country, and eventually collated into two volumes for broader distribution.

Hamilton emphasized the necessity of a central authority with the power to tax and enforce laws, citing specific failures under the Articles like the inability to generate revenue or maintain public order. Jay addressed the need for unity and the inadequacies of confederation in foreign diplomacy.

The Federalist Papers provided the framework needed to understand and eventually ratify the Constitution, remaining essential reading for anyone interested in the foundations of the American political system.

Key Arguments in the Federalist Papers

Among the key arguments presented in the Federalist Papers, three themes stand out:

- The need for a stronger central government

- The importance of checks and balances

- The dangers of factionalism

Federalist No. 23 , written by Alexander Hamilton, argued for a robust central government, citing the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton contended that empowering the central government with the means to enforce laws and collect taxes was essential for the Union's survival and prosperity.

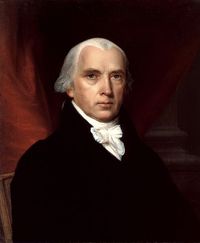

In Federalist No. 51 , James Madison addressed the principle of checks and balances, arguing that the structure of the new government would prevent any single branch from usurping unrestrained power. Each branch—executive, legislative, and judicial—would have the means and motivation to check the power of the others, safeguarding liberty.

Federalist No. 10 , also by Madison, delved into the dangers posed by factions—groups united by a common interest adverse to the rights of others or the interests of the community. Madison acknowledged that factions are inherent within any free society and cannot be eliminated without destroying liberty. He argued that a well-constructed Union would break and control the violence of faction by filtering their influence through a large republic.

Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 brought the concept of judicial review to the forefront, establishing the judiciary as a guardian of the Constitution and essential for interpreting laws and checking the actions of the legislature and executive branches. 1

The Federalist Papers meticulously dismantled Anti-Federalist criticisms and showcased how the proposed system would create a stable and balanced government capable of both governing effectively and protecting individual rights. These essays remain seminal works for understanding the underpinnings of the United States Constitution and the brilliance of the Founding Fathers.

Analysis of Federalist 10 and Federalist 51

Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 are two of the most influential essays within the Federalist Papers, elucidating fundamental principles that continue to support the American political system. They were carefully crafted to address the concerns of Anti-Federalists who feared that the new Constitution might pave the way for tyranny and undermine individual liberties.

In Federalist 10 , James Madison addresses the inherent dangers posed by factions. He argues that a large republic is the best defense against their menace, as it becomes increasingly challenging for any single faction to dominate in a sprawling and diverse nation. The proposed Constitution provides a systemic safeguard against factionalism by implementing a representative form of government, where elected representatives act as a filtering mechanism.

Federalist 51 further elaborates on how the structure of the new government ensures the protection of individual rights through a system of checks and balances. Madison supports the division of government into three coequal branches, each equipped with sufficient autonomy and authority to check the others. He asserts that ambition must be made to counteract ambition, emphasizing that the self-interest of individuals within each branch would serve as a natural check on the others. 2

Madison also delves into the need for a bicameral legislature, comprising the House of Representatives and the Senate. This dual structure aims to balance the demands of the majority with the necessity of protecting minority rights, thereby preventing majoritarian tyranny.

Together, Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 form a comprehensive blueprint for a resilient and balanced government. Madison's insights address both the internal and external mechanisms necessary to guard against tyranny and preserve individual liberties. These essays speak to the enduring principles that have guided the American republic since its inception, proving the timeless wisdom of the Founding Fathers and the genius of the American Constitution.

Impact and Legacy of the Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers had an immediate and profound impact on the ratification debates, particularly in New York, where opposition to the Constitution was fierce and vocal. Alexander Hamilton, a native of New York, understood the weight of these objections and recognized that New York's support was crucial for the Constitution's success, given the state's economic influence and strategic location. The essays were carefully crafted to address New Yorkers' specific concerns and to persuade undecided delegates.

The comprehensive detail and logical rigor of the Federalist Papers succeeded in swaying public opinion. They systematically addressed Anti-Federalist critiques, such as the fear that a strong central government would trample individual liberties. Hamilton, Madison, and Jay argued for the necessity of a powerful, yet balanced federal system, capable of uniting the states and ensuring both national security and economic stability.

In New York, the Federalist essays began appearing in newspapers in late 1787 and continued into 1788. Despite opposition, especially from influential Anti-Federalists like Governor George Clinton, the arguments laid out by "Publius" played a critical role in turning the tide. They provided Federalists with a potent arsenal of arguments to counter Anti-Federalists at the state's ratification convention. When the time came to vote, the persuasive power of the essays contributed significantly to New York's eventual decision to ratify the Constitution by a narrow margin.

The impact of the Federalist Papers extends far beyond New York. They influenced debates across the fledgling nation, helping to build momentum towards the required nine-state ratification. Their detailed exposition of the Constitution's provisions and the philosophic principles underlying them offered critical insights for citizens and delegates in other states. The essays became indispensable tools in the broader national dialogue about what kind of government the United States should have, guiding the country towards ratification.

The long-term significance of the Federalist Papers in American political thought and constitutional interpretation is substantial. Over the centuries, they have become foundational texts for understanding the intentions of the Framers. Jurists, scholars, and lawmakers have turned to these essays for guidance on interpreting the Constitution's provisions, shaping American constitutional law. Judges, including the justices of the Supreme Court, have frequently cited these essays in landmark rulings to elucidate the Framers' intent.

The Federalist Papers have profoundly influenced the development of American political theory, contributing to discussions about federalism, republicanism, and the balance between liberty and order. Madison's arguments in Federalist No. 10 have become keystones in the study of pluralism and the mechanisms by which diverse interests can coexist within a unified political system.

The essays laid the groundwork for ongoing debates about the role of the federal government, the balance of power among its branches, and the preservation of individual liberties. They provided intellectual support for later expansions of constitutional rights through amendments and judicial interpretations.

Their legacy also includes a robust defense of judicial review and the judiciary's role as a guardian of the Constitution. Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 provided a compelling argument for judicial independence, which has been a cornerstone in maintaining the rule of law and protecting constitutional principles against transient political pressures.

The Federalist Papers were crucial in the ratification of the Constitution, particularly in the contentious atmosphere of New York's debates. Their immediate effect was to facilitate the acceptance of the new governing framework. In the long term, their meticulously argued positions have provided a lasting blueprint for constitutional interpretation, influencing American political thought and practical governance for over two centuries. The essays stand as a testament to the foresight and philosophical acumen of the Founding Fathers, continuing to illuminate the enduring principles of the United States Constitution.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

How Did Magna Carta Influence the U.S. Constitution?

The 13th‑century pact inspired the U.S. Founding Fathers as they wrote the documents that would shape the nation.

The Founding Fathers Feared Political Factions Would Tear the Nation Apart

The Constitution's framers viewed political parties as a necessary evil.

Checks and Balances

Separation of Powers The idea that a just and fair government must divide power between various branches did not originate at the Constitutional Convention, but has deep philosophical and historical roots. In his analysis of the government of Ancient Rome, the Greek statesman and historian Polybius identified it as a “mixed” regime with three branches: […]

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- ENCYCLOPEDIA

- IN THE CLASSROOM

Home » Articles » Topic » Groups and Organizations » Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalists

Mitzi Ramos

and John R. Vile

The Anti-Federalists's opposition to ratifying the Constitution was a powerful force in the origin of the Bill of Rights to protect Americans' civil liberties. The Anti-Federalists were chiefly concerned with too much power invested in the national government at the expense of states. (Howard Chandler Christy's interpretation of the signing of the Constitution, painted in 1940.)

The Anti-Federalists opposed the ratification of the 1787 U.S. Constitution because they feared that the new national government would be too powerful and thus threaten individual liberties, given the absence of a bill of rights.

Their opposition was an important factor leading to the adoption of the First Amendment and the other nine amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights .

The political split between Anti-Federalists and the Federalists began in the summer of 1787 when 55 delegates attended the Constitutional Convention meeting in Philadelphia to draw up a new plan of government to replace the government under the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation was created by the Second Continental Congress and ratified by the states in 1781. The delegates in 1787 had decided to draw up a new plan of government rather than simply revise the Articles.

The Articles had created a confederal government, with a Congress with limited authority and states retaining primary sovereignty. The proposed new Constitution created a federal government in which national laws were supreme over state laws and in which the government could act directly upon individuals. Whereas the Articles had a single branch of government concentrated in a unicameral (one house) Congress in which each state had an equal vote, the new Constitution provided for three independent branches with a bicameral Congress in which one house was represented according to population.

New constitution was not prefaced with declaration of rights

The new constitution primarily attempted to protect liberties against this more powerful government through a system of separation of powers, federalism and other checks and balance. Although it contained some explicit prohibitions, such as those on the states in Article I, Section 9, and those on the states in Article I, Section 10, it was not, like many state counterparts, prefaced with a declaration or bill of rights such as the Virginia Declaration of Rights that George Mason had authored.

Whereas the Articles had required unanimous state legislative consent to amendments, the new constitution provided that it would go into effect when ratified by 9 or more of the 13 states. Moreover, it provided that such ratification would be conducted by special state conventions rather than by existing state legislatures. Once ratified, the document could be amended by a special convention called by Congress at the request of two-thirds of the states or by amendments proposed by two-thirds majorities of both houses of Congress, which were subsequently ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures or by specially called state conventions.

Some delegates thought changes to federalist government too radical

From the outset of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, there were delegates who thought that these changes were too radical. Some delegates such as John Lansing Jr. and Robert Yates from New York and Luther Martin of Maryland, simply left the Convention, but even among those who stayed, three delegates (George Mason and Edmund Randolph of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts of Massachusetts) decided not to sign.

Of these individuals, George Mason might have been the most important because, just a week before the Constitution was signed, Mason had proposed the addition of a bill of rights, which 10 of 10 states voting had rejected as unnecessary. One of the reasons that Mason had offered for adding such a bill was that “it would give great quiet to the people” (Farrand, 1966, II, 587).

When the Constitution was sent to the states for ratification, supporters of the document, arguably seeking to minimize the differences between the proposed constitution and its predecessor, called themselves Federalists . Capitalizing on the fact that they were offering solutions to what they perceived to be the problems under the Articles, they further dubbed those who opposed ratification as Anti-Federalists.

Patrick Henry was an outspoken anti-Federalist. The Anti-Federalists included small farmers and landowners, shopkeepers, and laborers. When it came to national politics, they favored strong state governments, a weak central government, the direct election of government officials, short term limits for officeholders, accountability by officeholders to popular majorities, and the strengthening of individual liberties. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain, portrait by George Bagby Matthews and Thomas Sully)

Anti-Federalists were concerned about excessive power of national government

The Anti-Federalists included small farmers and landowners, shopkeepers, and laborers. When it came to national politics, they favored strong state governments, a weak central government, the direct election of government officials, short term limits for officeholders, accountability by officeholders to popular majorities, and the strengthening of individual liberties. In terms of foreign affairs, they were pro-French.

Federalists were, as a whole, better organized and connected. Writing under the pen name of Publius, Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay wrote a series of 85 powerful newspaper essays known as The Federalist Papers. To combat the Federalist campaign, the Anti-Federalists published a series of articles and delivered numerous speeches against ratification of the Constitution.

These independent writings and speeches have come to be known collectively as The Anti-Federalist Papers .

Although Patrick Henry , Melancton Smith, and others eventually came out publicly against the ratification of the Constitution, which they would vigorously debate in the state ratifying conventions, the majority of the Anti-Federalists advocated their position under pseudonyms . Nonetheless, historians have concluded that the major Anti-Federalist writers included Robert Yates (Brutus), most likely George Clinton (Cato), Samuel Bryan (Centinel), and either Melancton Smith or Richard Henry Lee (Federal Farmer).

By way of these speeches and articles, Anti-Federalists brought to light fears of:

- the excessive power of the national government at the expense of the state government;

- the disguised monarchic powers of the president;

- apprehensions about a federal court system and its control over the states;

- fears that Congress might seize too many powers under the necessary and proper clause and other open-ended provisions;

- concerns, partly based on the writing of the French philosopher, the Baron de Montesquieu and addressed in Federalist No. 10, that republican government could not work in a land the size of the United States;

- special concern over the role of the Senate in ratifying treaties without concurrence in the House of Representatives;

- fear that Congress was not large enough adequately to represent the people within the states;

- and their most successful argument against the adoption of the Constitution — the lack of a bill of rights to protect individual liberties.

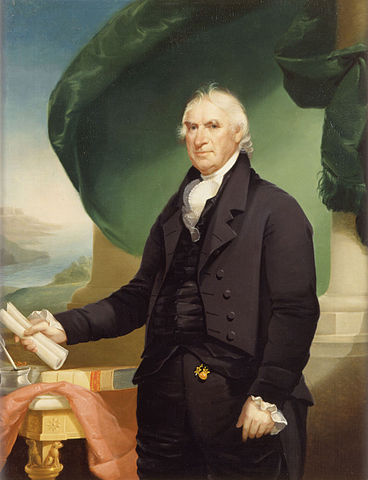

George Clinton was most likely a writer of The Anti-Federalist Papers under the pseudonym Cato. These papers were a series of articles published to combat the Federalist campaign. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain, portrait by Ezra Ames)

Anti-Federalists pressured for adoption of Bill of Rights

The Anti-Federalists failed to prevent the adoption of the Constitution, but their efforts were not entirely in vain. Even before the adoption of the First Amendment, the debates and their outcome thus vindicated the importance of freedom of speech and press in achieving national consensus. Moreover, Anti-Federalists, most notably Patrick Henry , acceded to the Convention and sought legal means of change once the document had been ratified because they believed that it had been properly ratified.

Although many Federalists initially argued against the necessity of a bill of rights to ensure passage of the Constitution, they promised to add amendments to it specifically protecting individual liberties. Upon ratification, James Madison introduced 12 amendments during the First Congress in 1789. The states ratified 10 of these, which took effect in 1791 and are known today collectively as the Bill of Rights .

Had Anti-Federalists drafted the amendments, they would have undoubtedly contained structural reforms within the new government that Federalists successfully avoided in part by heading off pressures for a second constitutional convention that might have reversed many of the provisions of the first. Madison’s hope for an amendment in the Bill of Rights that would limit the states was not adopted, undoubtedly because of opposition by Anti-Federalists who already feared the power of the new national government.

Although the Federalists and Anti-Federalists reached a compromise that led to the adoption of the Constitution, this harmony did not filter into the presidency of George Washington .

Political division within the cabinet of the newly created government emerged in 1792 over fiscal policy. Those who supported Alexander Hamilton’s aggressive policies and expansive constitutional interpretations formed the Federalist Party, while those, including some former Federalists, who supported Thomas Jefferson’s view favoring stricter constitutional construction and opposing the establishment of a national bank, the assumption of state debts, and other Hamiltonian proposals formed the Jeffersonian Party.

The Jeffersonian party, led by Jefferson and James Madison, became known as the Republican or Democratic-Republican Party, the precursor to the modern Democratic Party.

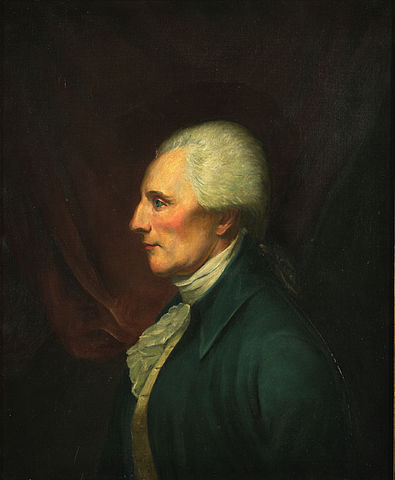

Richard Henry was a possible writer of anti-Federalist essays with the pseudonym Federal Farmer. (Image via National Portrait Gallery, public domain, portrait by Charles Wilson Peale)

Election of Jefferson repudiated the Federalist-sponsored Alien and Sedition Acts

The Democratic-Republican Party gained national prominence through the election of Thomas Jefferson as president in 1801.

This election is considered a turning point in U.S. history because it led to the first era of party politics, pitting the Federalist Party against the Democratic-Republican Party. This election is also significant because it served to repudiate the Federalist-sponsored Alien and Sedition Acts — which made it more difficult for immigrants to become citizens and criminalized oral or written criticisms of the government and its officials — and it shed light on the importance of party coalitions.

In fact, the Democratic-Republican Party proved to be more dominant due to the effective alliance it forged between the Southern agrarians and Northern city dwellers.

The election of James Madison in 1808 and James Monroe in 1816 further reinforced the importance of the dominant coalitions within the Democratic-Republican Party.

With the death of Alexander Hamilton and retirement of John Quincy Adams from politics, the Federalist Party disintegrated.

After the War of 1812 ended, partisanship subsided across the nation. In the absence of the Federalist Party, the Democratic-Republican Party stood unchallenged. The so-called Era of Good Feelings followed this void in party politics, but it did not last long with the Federalist Party later being replaced respectively by the Whig and Republican Parties.

Some scholars see echoes of the Federalist/Anti-Federalist debates in the continuing tension between those who emphasize state over national powers, in proposals to reduce and limit terms in public office, and in disagreements between those who are more likely to embrace new institutional changes and those who are fearful that they might lead to unintended negative consequences..

This article was originally published in 2009. Mitzi Ramos is an instructor of political science at Northeastern Illinois University. John R. Vile is the dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University and a history professor.

Send Feedback on this article

How To Contribute

The Free Speech Center operates with your generosity! Please donate now!

Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers

A compilation of our

11 Activities

Primary Source

1 Activities

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays arguing in support of the United States Constitution . Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay were the authors behind the pieces, and the three men wrote collectively under the name of Publius .

Seventy-seven of the essays were published as a series in The Independent Journal , The New York Packet , and The Daily Advertiser between October of 1787 and August 1788. They weren't originally known as the "Federalist Papers," but just "The Federalist." The final 8 were added in after.

At the time of publication, the authorship of the articles was a closely guarded secret. It wasn't until Hamilton's death in 1804 that a list crediting him as one of the authors became public. It claimed fully two-thirds of the essays for Hamilton. Many of these would be disputed by Madison later on, who had actually written a few of the articles attributed to Hamilton.

Once the Federal Convention sent the Constitution to the Confederation Congress in 1787, the document became the target of criticism from its opponents. Hamilton, a firm believer in the Constitution, wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."

Alexander Hamilton was the force behind the project, and was responsible for recruiting James Madison and John Jay to write with him as Publius. Two others were considered, Gouverneur Morris and William Duer . Morris rejected the offer, and Hamilton didn't like Duer's work. Even still, Duer managed to publish three articles in defense of the Constitution under the name Philo-Publius , or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written, in honor of the great Roman Publius Valerius Publicola . The original Publius is credited with being instrumental in the founding of the Roman Republic. Hamilton thought he would be again with the founding of the American Republic. He turned out to be right.

John Jay was the author of five of the Federalist Papers. He would later serve as Chief Justice of the United States. Jay became ill after only contributed 4 essays, and was only able to write one more before the end of the project, which explains the large gap in time between them.

Jay's Contributions were Federalist: No. 2 , No. 3 , No. 4 , No. 5 , and No. 64 .

James Madison , Hamilton's major collaborator, later President of the United States and "Father of the Constitution." He wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers, although Madison himself, and many others since then, asserted that he had written more. A known error in Hamilton's list is that he incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64 , has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that the disputed papers were written by Madison, but as the writers themselves released no complete list, no one will ever know for sure.

Opposition to the Bill of Rights

The Federalist Papers, specifically Federalist No. 84 , are notable for their opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights . Hamilton didn't support the addition of a Bill of Rights because he believed that the Constitution wasn't written to limit the people. It listed the powers of the government and left all that remained to the states and the people. Of course, this sentiment wasn't universal, and the United States not only got a Constitution, but a Bill of Rights too.

No. 1: General Introduction Written by: Alexander Hamilton October 27, 1787

No.2: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay October 31, 1787

No. 3: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 3, 1787

No. 4: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 7, 1787

No. 5: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 10, 1787

No. 6:Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 14, 1787

No. 7 The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 15, 1787

No. 8: The Consequences of Hostilities Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 20, 1787

No. 9 The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 21, 1787

No. 10 The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: James Madison November 22, 1787

No. 11 The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 24, 1787

No 12: The Utility of the Union In Respect to Revenue Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 27, 1787

No. 13: Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 28, 1787

No. 14: Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered Written by: James Madison November 30, 1787

No 15: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 1, 1787

No. 16: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 4, 1787

No. 17: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 5, 1787

No. 18: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 7, 1787

No. 19: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 8, 1787

No. 20: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 11, 1787

No. 21: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 12, 1787

No. 22: The Same Subject Continued: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 14, 1787

No. 23: The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 18, 1787

No. 24: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 19, 1787

No. 25: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 21, 1787

No. 26: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 22, 1787

No. 27: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 25, 1787

No. 28: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 26, 1787

No. 29: Concerning the Militia Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 9, 1788

No. 30: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 28, 1787

No. 31: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 1, 1788

No. 32: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 33: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 34: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 35: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 36: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 8, 1788

No. 37: Concerning the Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 11, 1788

No. 38: The Same Subject Continued, and the Incoherence of the Objections to the New Plan Exposed Written by: James Madison January 12, 1788

No. 39: The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 40: The Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined and Sustained Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 41: General View of the Powers Conferred by the Constitution Written by: James Madison January 19, 1788

No. 42: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 22, 1788

No. 43: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 23, 1788

No. 44: Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States Written by: James Madison January 25, 1788

No. 45: The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Union to the State Governments Considered Written by: James Madison January 26, 1788

No. 46: The Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared Written by: James Madison January 29, 1788

No. 47: The Particular Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Power Among Its Different Parts Written by: James Madison January 30, 1788

No. 48: These Departments Should Not Be So Far Separated as to Have No Constitutional Control Over Each Other Written by: James Madison February 1, 1788

No. 49: Method of Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government Written by: James Madison February 2, 1788

No. 50: Periodic Appeals to the People Considered Written by: James Madison February 5, 1788

No. 51: The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments Written by: James Madison February 6, 1788

No. 52: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 8, 1788

No. 53: The Same Subject Continued: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 9, 1788

No. 54: The Apportionment of Members Among the States Written by: James Madison February 12, 1788

No. 55: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 13, 1788

No. 56: The Same Subject Continued: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 16, 1788

No. 57: The Alleged Tendency of the New Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many Written by: James Madison February 19, 1788

No. 58: Objection That The Number of Members Will Not Be Augmented as the Progress of Population Demands Considered Written by: James Madison February 20, 1788

No. 59: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 22, 1788

No. 60: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 23, 1788

No. 61: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 26, 1788

No. 62: The Senate Written by: James Madison February 27, 1788

No. 63: The Senate Continued Written by: James Madison March 1, 1788

No. 64: The Powers of the Senate Written by: John Jay March 5, 1788

No. 65: The Powers of the Senate Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 7, 1788

No. 66: Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 8, 1788

No. 67: The Executive Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 11, 1788

No. 68: The Mode of Electing the President Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 12, 1788

No. 69: The Real Character of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 14, 1788

No. 70: The Executive Department Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 15, 1788

No. 71: The Duration in Office of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 18, 1788

No. 72: The Same Subject Continued, and Re-Eligibility of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 19, 1788

No. 73: The Provision For The Support of the Executive, and the Veto Power Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 21, 1788

No. 74: The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 25, 1788

No. 75: The Treaty Making Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 26, 1788

No. 76: The Appointing Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 1, 1788

No. 77: The Appointing Power Continued and Other Powers of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 2, 1788

No. 78: The Judiciary Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 14, 1788

No. 79: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 18, 1788

No. 80: The Powers of the Judiciary Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 21, 1788

No. 81: The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 25, 1788

No. 82: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 2, 1788

No. 83: The Judiciary Continued in Relation to Trial by Jury Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 5, 1788

No. 84: Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 16, 1788

No. 85: Concluding Remarks Written by: Alexander Hamilton August 13, 1788

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Oak Hill Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Oak Hill Publishing Company. Box 6473, Naperville, IL 60567 For questions or comments about this site please email us at [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Federalist Papers were written and published to urge New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution, which was drafted in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. In lobbying for adoption of the Constitution over the existing Articles of Confederation, the essays explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail.

These issues prompted the creation of the Federalist Papers, a series of essays aimed at advocating for a stronger central government under the newly proposed Constitution. This article will examine the purpose, key arguments, and lasting impact of these influential writings.

The Federalist Papers were written to help convince Americans that the Constitution would not threaten freedom. Federalist Paper authors, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay teamed up in 1788 to write a series of essays in defense of the Constitution.

The Anti-Federalist papers failed to halt the ratification of the Constitution but they succeeded in influencing the first assembly of the United States Congress to draft the Bill of Rights. [2] These works were authored primarily by anonymous contributors using pseudonyms such as "Brutus" and the "Federal Farmer." Unlike the Federalists, the ...

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first...

The Anti-Federalists opposed the ratification of the 1787 U.S. Constitution because they feared that the new national government would be too powerful and thus threaten individual liberties, given the absence of a bill of rights.

Why did the Anti-Federalist so strongly oppose the proposed Constitution? In this rapid-fire episode of BRI’s Primary Source Essentials and Brutus 1 summary, learn the arguments made in Brutus 1 against the Constitution.

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays arguing in support of the United States Constitution. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay were the authors behind the pieces, and the three men wrote collectively under the name of Publius.

Core readings for a study of the Constitution include the carefully reasoned essays written by the most accomplished political theorists of the day—including the Federalist Papers by Publius (James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay), and Anti-Federalist essays by Cato, Centinel, the Federal Farmer, the Columbian Patriot, and other ...

Federalist papers, series of 85 essays on the proposed new Constitution of the United States and on the nature of republican government, published between 1787 and 1788 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in an effort to persuade New York state voters to support ratification.