Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER GUIDE

- 12 May 2021

Good presentation skills benefit careers — and science

- David Rubenson 0

David Rubenson is the director of the scientific-communications firm No Bad Slides ( nobadslides.com ) in Los Angeles, California.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

A better presentation culture can save the audience and the larger scientific world valuable time and effort. Credit: Shutterstock

In my experience as a presentation coach for biomedical researchers, I have heard many complaints about talks they attend: too much detail, too many opaque visuals, too many slides, too rushed for questions and so on. Given the time scientists spend attending presentations, both in the pandemic’s virtual world and in the ‘face-to-face’ one, addressing these complaints would seem to be an important challenge.

I’m dispirited that being trained in presentation skills, or at least taking more time to prepare presentations, is often not a high priority for researchers or academic departments. Many scientists feel that time spent improving presentations detracts from research or clocking up the numbers that directly affect career advancement — such as articles published and the amount of grant funding secured. Add in the pressing, and sometimes overwhelming, bureaucratic burdens associated with working at a major biomedical research institute, and scientists can simply be too busy to think about changing the status quo.

Improving presentations can indeed be time-consuming. But there are compelling reasons for researchers to put this near the top of their to-do list.

You’re probably not as good a presenter as you think you are

Many scientists see problems in colleagues’ presentations, but not their own. Having given many lousy presentations, I know that it is all too easy to receive (and accept) plaudits; audiences want to be polite. However, this makes it difficult to get an accurate assessment of how well you have communicated your message.

Why your scientific presentation should not be adapted from a journal article

With few exceptions, biomedical research presentations are less effective than the speaker would believe. And with few exceptions, researchers have little appreciation of what makes for a good presentation. Formal training in presentation techniques (see ‘What do scientists need to learn?’) would help to alleviate these problems.

Improving a presentation can help you think about your own research

A well-designed presentation is not a ‘data dump’ or an exercise in advanced PowerPoint techniques. It is a coherent argument that can be understood by scientists in related fields. Designing a good presentation forces a researcher to step back from laboratory procedures and organize data into themes; it’s an effective way to consider your research in its entirety.

You might get insights from the audience

Overly detailed presentations typically fill a speaker’s time slot, leaving little opportunity for the audience to ask questions. A comprehensible and focused presentation should elicit probing questions and allow audience members to suggest how their tools and methods might apply to the speaker’s research question.

Many have suggested that multidisciplinary collaborations, such as with engineers and physical scientists, are essential for solving complex problems in biomedicine. Such innovative partnerships will emerge only if research is communicated clearly to a broad range of potential collaborators.

It might improve your grant writing

Many grant applications suffer from the same problem as scientific presentations — too much detail and a lack of clearly articulated themes. A well-designed presentation can be a great way to structure a compelling grant application: by working on one, you’re often able to improve the other.

It might help you speak to important, ‘less-expert’ audiences

As their career advances, it is not uncommon for scientists to increasingly have to address audiences outside their speciality. These might include department heads, deans, philanthropic foundations, individual donors, patient groups and the media. Communicating effectively with scientific colleagues is a prerequisite for reaching these audiences.

Collection: Conferences

Better presentations mean better science

An individual might not want to spend 5 hours improving their hour-long presentation, but 50 audience members might collectively waste 50 hours listening to that individual’s mediocre effort. This disparity shows that individual incentives aren’t always aligned with society’s scientific goals. An effective presentation can enhance the research and critical-thinking skills of the audience, in addition to what it does for the speaker.

What do scientists need to learn?

Formal training in scientific presentation techniques should differ significantly from programmes that stress the nuances of public speaking.

The first priority should be to master basic presentation concepts, including:

• How to build a concise scientific narrative.

• Understanding the limitations of slides and presentations.

• Understanding the audience’s time and attention-span limitations .

• Building a complementary, rather than repetitive, relationship between what the speaker says and what their slides show.

The training should then move to proper slide design, including:

• The need for each slide to have an overarching message.

• Using slide titles to help convey that message.

• Labelling graphs legibly.

• Deleting superfluous data and other information.

• Reducing those 100-word text slides to 40 words (or even less) without losing content.

• Using colour to highlight categories of information, rather than for decoration.

• Avoiding formats that have no visual message, such as data tables.

A well-crafted presentation with clearly drawn slides can turn even timid public speakers into effective science communicators.

Scientific leaders have a responsibility to provide formal training and to change incentives so that researchers spend more time improving presentations.

A dynamic presentation culture, in which every presentation is understood, fairly critiqued and useful for its audience, can only be good for science.

Nature 594 , S51-S52 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01281-8

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Related Articles

- Conferences and meetings

- Research management

Grass-roots pressure grows to boost support for breastfeeding scientists

Career Feature 08 NOV 24

‘Anyone engaging in scientific practice shouldn’t be excluded’: The United Kingdom’s only Black chemistry professor, on diversity

Career Q&A 06 NOV 24

Science communication will benefit from research integrity standards

Editorial 06 NOV 24

ChatGPT is transforming peer review — how can we use it responsibly?

World View 05 NOV 24

I botched my poster presentation — how do I perform better next time?

Career Feature 27 SEP 24

Academics say flying to meetings harms the climate — but they carry on

News 13 SEP 24

Distributed peer review: how Ukraine has reaped the benefits and minimized the risks

Correspondence 05 NOV 24

Is there a ‘Goldilocks zone’ for paper length?

Nature Index 05 NOV 24

2025 International Young Scholars Forum of International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University

Researchers in the fields of life sciences, healthcare, or the intersection of medicine, industry, and information technology.

Yiwu, Zhejiang, China

International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University

Tenure-track Assistant Professor - Inflammation, Metabolism, or Therapeutic Targeting

Washington D.C. (US)

The George Washington University

JUNIOR GROUP LEADER

JUNIOR GROUP LEADER Professor position The International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Warsaw (IIMCB), Poland

Poland (PL)

International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Warsaw

Postdoc, Student, and Technician Positions at Harvard Medical School—Most Recent Nature Manuscript!

Immediate positions are available to study the novel "stem-immunology". A manuscript from our group has been most recently accepted in Nature.

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School Center for Inflammation Research

Postdoctoral fellow

Postdoctoral position in Immuno oncology research in NCI designated Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami

Miami, Florida (US)

Sylvester comprehensive cancer center, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

Advantages and Disadvantages of Presentation

Curious about the Advantages and Disadvantages of Presentations? Presentations can effectively convey information, engage audiences, and enhance understanding. However, they may also pose challenges, such as time constraints and reliance on technology. This blog explores both the benefits and drawbacks of using Presentations.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Effective Communication Skills

- Presenting with Impact Training

- Interpersonal Skills Training Course

- Effective Presentation Skills & Techniques

- Public Speaking Course

Have you ever wondered why some Presentations captivate audiences while others fall flat? Or how you can leverage the strengths of Presentations to enhance your communication skills? Presentations are a strong tool for conveying information, but what are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Presentation methods? In this blog, we’ll explore the key benefits and potential drawbacks of using Presentations in various settings.

Understanding the Advantages and Disadvantages of Presentation techniques can help you make informed decisions about when and how to use them effectively. Ready to elevate your Presentation game and avoid common pitfalls? Let’s dive in and discover the best practices for creating impactful Presentations!

Table of Contents

1) What is a Presentation: A Brief Introduction

2) Advantages of Presentations

3) Disadvantages of Presentations

4) How to Make a Successful Presentation?

5) Conclusion

What is a Presentation: A Brief Introduction

A Presentation is a method of conveying information, ideas, or data to an audience using visual aids and spoken words. It can be formal or informal and is used in various settings, including business meetings, educational environments, conferences, and public speaking engagements. Presenters use visual elements like slides, charts, graphs, images, and multimedia to support and enhance their spoken content. The aim is to engage the audience, communicate the message effectively, and leave a lasting impact by focusing on the key elements of presentation skills ..

The success of a Presentation hinges on the presenter’s ability to organise content coherently, engage the audience, and deliver information clearly and compellingly. Moreover, Presentation Skill s are applicable to a wide range of scenarios, from business proposals and academic research to sales pitches and motivational speeches.

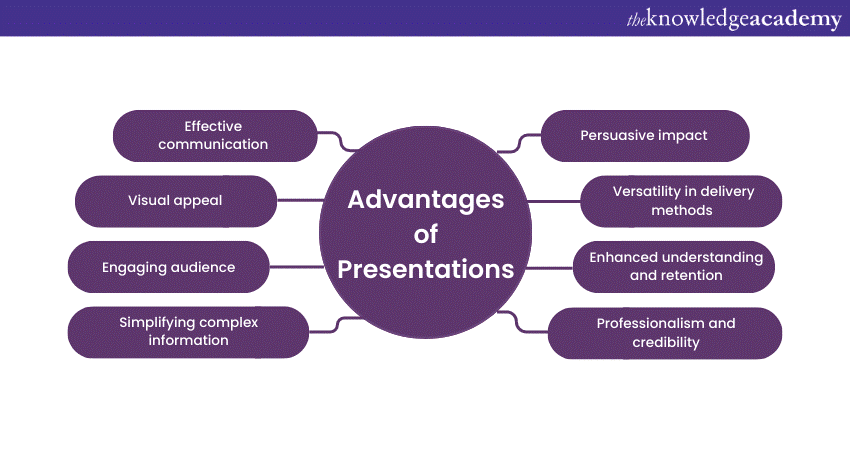

Advantages of Presentations

1) Effective Communication

One of the primary advantages of Presentations is their ability to facilitate effective communication . Whether you're addressing a small group of colleagues or a large audience at a conference, Presentations help you to convey your message clearly and succinctly. By structuring your content and using visuals, you can ensure that your key points are highlighted and easily understood by the audience.

2) Visual Appeal

"Seeing is believing," and Presentations capitalise on this aspect of human psychology. The use of visuals, such as charts, graphs, images, and videos, enhances the overall appeal of the content. These visual aids not only make the information more engaging but also help reinforce the main ideas, making the Presentation more memorable for the audience.

3) Engaging the Audience

Captivating your audience's attention is crucial for effective communication. Presentations provide ample opportunities to engage your listeners through various means. By incorporating storytelling , anecdotes, and real-life examples, you can nurture an emotional connection with your audience. Additionally, interactive elements like polls, quizzes, and group activities keep the audience actively involved throughout the Presentation.

4) Simplifying Complex Information

Complex ideas and data can often be overwhelming, making it challenging to convey them effectively. However, Presentations excel in simplifying intricate information. By simplifying complex concepts into clear and interconnected slides, you can present the information in a logical sequence, ensuring that the audience grasps the content more easily.

Revolutionise your classroom experience with our Blended Learning Essentials Course – book your spot now!

5) Persuasive Impact

Presentations are powerful tools for persuasion and influence. Whether you're convincing potential clients to invest in your product, advocating for a particular cause, or delivering a motivational speech, a well-crafted Presentation can sway the audience's opinions and inspire action. The combination of visual and verbal elements enables you to make a compelling case for your ideas, leaving a lasting impact on the listeners.

6) Versatility in Delivery Methods

Another advantage of Presentations lies in their flexibility and versatility in terms of delivery methods. Gone are the days when Presentations were limited to in-person meetings. Today, technology allows presenters to reach a wider audience through various platforms, including webinars, online videos, and virtual conferences. This adaptability makes Presentations an ideal choice for modern communication needs.

7) Enhanced Understanding and Retention

When information is presented in a visually appealing and structured manner, it aids in better understanding and retention. Human brains process visuals faster and more effectively than plain text, making Presentations an ideal medium for conveying complex concepts. The combination of visual elements and spoken words create a multi-sensory experience, leading to increased information retention among the audience.

8) Professionalism and Credibility

In professional settings, well-designed Presentations lend an air of credibility and professionalism to the presenter and the topic being discussed. A thoughtfully crafted Presentation shows that the presenter has put effort into preparing and organising the content, which in turn enhances the audience's trust and receptiveness to the information presented. Explore more on the principles of presentation to improve your skills.

Learn to captivate any audience with confidence and clarity – join our Presentation Skills Course and transform your communication abilities!

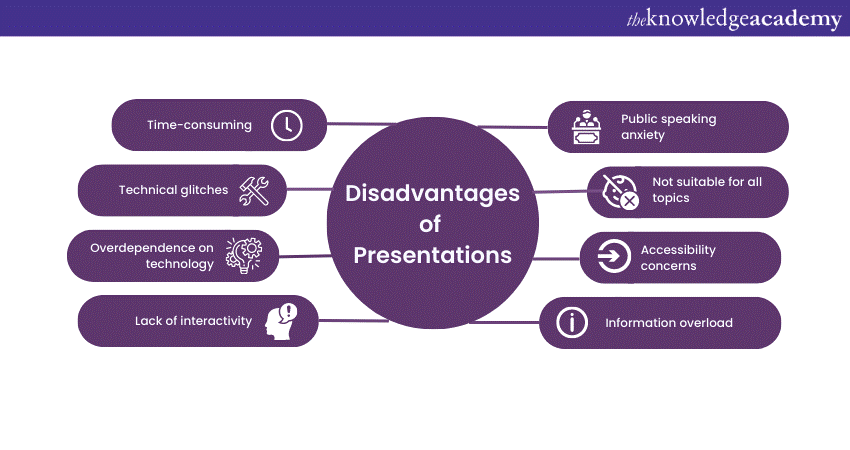

Disadvantages of Presentations

1) Time-consuming

Creating a compelling Presentation can be a time-consuming process. From researching and gathering relevant information to designing visually appealing slides, a significant amount of effort goes into ensuring that the content is well-structured and impactful. This time investment can be challenging, especially when presenters have tight schedules or are faced with last-minute Presentation requests.

2) Technical Glitches

Presentations heavily rely on technology, and technical glitches can quickly turn a well-prepared Presentation into a frustrating experience. Projectors may malfunction, slides might not load correctly, or audiovisual components may fail to work as expected. Dealing with such technical issues during a Presentation can disrupt the flow and distract both the presenter and the audience.

Turn raw data to actionable insights with our Data Analysis Skills Training – join us and advance your analytical abilities!

3) Overdependence on Technology

In some cases, presenters may become overly reliant on the visuals and technology, neglecting the importance of direct engagement with the audience. Overloaded slides with excessive text can make presenters read directly from the slides, undermining the personal connection and interaction with the listeners. This overdependence on technology can lead to a lack of spontaneity and authenticity during the Presentation.

4) Lack of Interactivity

Traditional Presentations, particularly those delivered in large auditoriums, may lack interactivity and real-time feedback. In comparison, modern Presentation formats can incorporate interactive elements; not all Presentations provide opportunities for audience participation or discussions. This one-sided communication can lead to reduced engagement and limited opportunities for clarifying doubts or addressing queries.

5) Public Speaking Anxiety

For many individuals, public speaking can be a nerve-wracking experience. Presenting in front of an audience, especially in formal settings, can trigger anxiety and stage fright. This anxiety may affect the presenter's delivery and confidence, impacting the overall effectiveness of the Presentation. Overcoming public speaking anxiety requires practice, self-assurance, and effective stress management techniques.

6) Not Suitable for all Topics

While Presentations are an excellent medium for conveying certain types of information, they may not be suitable for all topics. Some subjects require in-depth discussions, hands-on demonstrations, or interactive workshops, which may not align well with the traditional slide-based Presentation format. Choosing the appropriate communication method for specific topics is crucial to ensure effective knowledge transfer and engagement.

7) Accessibility Concerns

In a diverse audience, some individuals may face challenges in accessing and comprehending Presentation materials. For example, people with visual impairments may find it difficult to interpret visual elements, while those with hearing impairments may struggle to follow the spoken content without proper captions or transcripts. Addressing accessibility concerns is vital to ensure inclusivity and equal participation for all attendees.

8) Information Overload

Presentations that bombard the audience with excessive information on each slide can lead to information overload. When the audience is overwhelmed with data, they may struggle to absorb and retain the key points. Presenters should strike a balance between providing adequate information and keeping the content concise and focused.

How to Make a Successful Presentation?

Now that we know the Advantages and Disadvantages of Presentations, we will provide you with some tips on how to make a successful Presentation.

1) Understand your audience's needs and interests to tailor your content accordingly.

2) Begin with an attention-grabbing introduction to captivate the audience from the Start of Presentation .

3) Structure your Presentation in a clear and coherent manner with a beginning, middle, and end.

4) Keep slides simple and avoid overcrowding with excessive text; use bullet points and keywords.

5) Incorporate high-quality images, graphs, and charts to enhance understanding and engagement.

6) Rehearse your Presentation multiple times to improve your delivery and confidence.

7) Show passion for your topic and maintain good eye contact to build trust with the audience.

8) Include relevant anecdotes and case studies to make your points more relatable and memorable.

9) Encourage audience participation through questions, polls, or discussions to keep them engaged.

10) Respect the allotted time for your Presentation and pace your delivery accordingly.

11) Summarise your key points and leave the audience with a clear takeaway or call to action.

12) Request feedback after the Presentation to identify areas for improvement and grow as a presenter.

Sign up for our Presenting With Impact Training and transform your Presentations with impactful skills.

Conclusion

Understanding the Advantages and Disadvantages of Presentation methods can significantly enhance your communication skills and audience engagement. By comprehending the strengths and mitigating the weaknesses, you can create impactful Presentations that leave a lasting impression. So, apply these insights and watch your effectiveness soar!

Advance you career with our Business Writing Course – register today and gain the skills to communicate with clarity and confidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Strong Presentation skills can boost your ability to clearly and persuasively communicate ideas. This can lead to increased networking opportunities, as people are more likely to connect with and refer to someone who presents confidently and effectively.

Good Presentation skills are crucial for educators and trainers as they ensure information is delivered clearly and engagingly. Effective Presentations help maintain audience interest, facilitate better understanding, and promote active participation, ultimately leading to improved learning outcomes.

The Knowledge Academy takes global learning to new heights, offering over 30,000 online courses across 490+ locations in 220 countries. This expansive reach ensures accessibility and convenience for learners worldwide.

Alongside our diverse Online Course Catalogue, encompassing 17 major categories, we go the extra mile by providing a plethora of free educational Online Resources like News updates, Blogs , videos, webinars, and interview questions. Tailoring learning experiences further, professionals can maximise value with customisable Course Bundles of TKA .

The Knowledge Academy’s Knowledge Pass , a prepaid voucher, adds another layer of flexibility, allowing course bookings over a 12-month period. Join us on a journey where education knows no bounds.

The Knowledge Academy offers various Presentation Skills Training , including the Data Analysis Skills Course, Blended Learning essentials Course, and Business Writing Course. These courses cater to different skill levels, providing comprehensive insights into Presentation Skills .

Our Business Skills Blogs cover a range of topics related to Presentation Skills, offering valuable resources, best practices, and industry insights. Whether you are a beginner or looking to advance your Business Skills, The Knowledge Academy's diverse courses and informative blogs have got you covered.

Upcoming Business Skills Resources Batches & Dates

Fri 6th Dec 2024

Fri 3rd Jan 2025

Fri 7th Mar 2025

Fri 2nd May 2025

Fri 4th Jul 2025

Fri 5th Sep 2025

Fri 7th Nov 2025

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Biggest black friday sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- ISO 9001 Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Scientific Presenting: Using Evidence-Based Classroom Practices to Deliver Effective Conference Presentations

Lisa a corwin, amy prunuske, shannon b seidel.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*Address correspondence to: Shannon B. Seidel ( [email protected] ).

Received 2017 Aug 1; Revised 2017 Oct 26; Accepted 2017 Oct 27.

This article is distributed by The American Society for Cell Biology under license from the author(s). It is available to the public under an Attribution–Noncommercial–Share Alike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons License.

Scientific presenting is the use of scientific teaching principles—active learning, equity, and assessment—in conference presentations to improve learning, engagement, and inclusiveness. This essay presents challenges presenters face and suggestions for how presenters can incorporate active learning strategies into their scientific presentations.

Scientists and educators travel great distances, spend significant time, and dedicate substantial financial resources to present at conferences. This highlights the value placed on conference interactions. Despite the importance of conferences, very little has been studied about what is learned from the presentations and how presenters can effectively achieve their goals. This essay identifies several challenges presenters face when giving conference presentations and discusses how presenters can use the tenets of scientific teaching to meet these challenges. We ask presenters the following questions: How do you engage the audience and promote learning during a presentation? How do you create an environment that is inclusive for all in attendance? How do you gather feedback from the professional community that will help to further advance your research? These questions target three broad goals that stem from the scientific teaching framework and that we propose are of great importance at conferences: learning, equity, and improvement. Using a backward design approach, we discuss how the lens of scientific teaching and the use of specific active-learning strategies can enhance presentations, improve their utility, and ensure that a presentation is broadly accessible to all audience members.

Attending a conference provides opportunities to share new discoveries, cutting-edge techniques, and inspiring research within a field of study. Yet after presenting at some conferences, you might leave feeling as though you did not connect with the audience, did not receive useful feedback, or are unsure of where you fit within the professional community. Deciding what to cover in a presentation may be daunting, and you may worry that the audience did not engage in your talk. Likewise, for audience members, the content of back-to-back talks may blur together, and they may get lost in acronyms or other unfamiliar jargon. Audience members who are introverted or new to the field may feel intimidated about asking a question in front of a large group containing well-known, outspoken experts. After attending a conference, one may leave feeling curious and excited or exhausted and overwhelmed, wondering what was gained from presenting or attending.

Conferences vary widely in purpose and location, ranging from small conferences hosted within home institutions to large international conferences featuring experts from around the world. The time and money spent to host, attend, and present at conferences speaks to the value placed on engaging in these professional interactions. Despite the importance of conferences to professional life, there is rarely time to reflect on what presenters and other conference attendees learn from participating in conferences or how conferences promote engagement and equity in the field as a whole. A significant portion of most conference time is devoted to the delivery of oral presentations, which traditionally are delivered in a lecture style, with questions being initiated by a predictable few during question-and-answer sessions.

In this essay, we discuss how you can use a backward design approach and scientific presenting strategies to overcome three key challenges to effectively presenting to diverse conference audiences. The challenges we consider here include the following:

Engagement in learning: ensuring that your audience is engaged and retains what is important from a talk

Promoting equity: creating an environment that is inclusive of all members of the research field

Receiving feedback: gathering input from the professional community to improve as a researcher and presenter

At conferences, learning and advancement of a field is paramount, similar to more formal educational settings. Thus, we wrote these presenting challenges to align with the central themes presented in the scientific teaching framework developed by Handelsman and colleagues (2007) . “Learning” aligns with “active learning,” “equity” with “diversity,” and “feedback” with “assessment.” Using the scientific teaching framework and a backward design approach, we propose using evidence-based teaching strategies for scientific presenting in order to increase learning, equity, and quality feedback. We challenge you , the presenter, to consider how these strategies might benefit your future presentations.

BACKWARD DESIGN YOUR PRESENTATION: GOALS AND AUDIENCE CONSIDERATIONS

How will you define the central goals of your presentation and frame your presentation based on these goals? Begin with the end in mind by clearly defining your presentation goals before developing content and activities. This is not unlike the process of backward design used to plan effective learning experiences for students ( McTighe and Thomas, 2003 ). Consider what you, as a presenter, want to accomplish. You may want to share results supporting a novel hypothesis that may impact the work of colleagues in your field or disseminate new techniques or methodologies that could be applied more broadly. You may seek feedback about an ongoing project. Also consider your audience and what you hope they will gain from attending. You may want to encourage your colleagues to think in new and different ways or to create an environment of collegiality. It is good to understand your audience’s likely goals, interests, and professional identities before designing your presentation.

How can you get to know these important factors about your audience? Although it may not be possible to predict or know all aspects of your audience, identify sources of information you can access to learn more about them. Conference organizers, the website for the conference, and previous attendees may be good sources of information about who might be in attendance. Conference organizers may have demographic information about the institution types and career stages of the audience. The website for a conference or affiliated society often describes the mission of the organization or conference. Finally, speaking with individuals who have previously attended the conference may help you understand the culture and expectations of your audience. This information may enable you to tailor your talk and select strategies that will engage and resonate with audience members of diverse backgrounds. Most importantly, reflecting on the information you gather will allow you to evaluate and better define your presentation goals.

Before designing your presentation, write between two and five goals you have for yourself or your audience (see Vignettes 1 and 2 for sample goals). Prioritize your goals and evaluate which can be accomplished with the time, space, and audience constraints you face. Once you have established both your goals and knowledge of who might attend your talk, it is time to design your talk. The Scientific Presenting section that follows offers specific design suggestions to engage the audience in learning, promote equity, and receive high-quality feedback.

Situation: Mona Harrib has been asked to give the keynote presentation at a regional biology education research conference. As a leader in the field, Mona is well known and respected, and she has a good grasp on where the field has been and where it is going now.

Presentation Goals: She has three goals she wants to accomplish with her presentation: 1) to introduce her colleagues to the self-efficacy framework, 2) to provide new members of her field opportunities to learn about where the field has been, and 3) to connect these new individuals with others in the field.

Scientific Presenting Strategy: Mona has 50 minutes for her presentation, with 10 minutes for questions. Her opening slide, displayed as people enter the room, encourages audience members to “sit next to someone you have not yet spoken to.” Because her talk will discuss self-efficacy theory and the various origins of students’ confidence in their ability to do science, she begins by asking the audience members to introduce themselves to their neighbors and to describe an experience in which they felt efficacious or confident in their ability to do something and why they felt confident. She circulates around the room, and asks five groups to share their responses. This provides an audience-generated foundation that she uses to explain the framework in more detail. For historical perspective, she relates each framework component back to prior research in the field. She ends with some recent work from her research group and asks participants to discuss with their partners how the framework could be used to explain the results of her recent study. She again gathers and reports several examples to the whole group that illustrate ways in which the data might be interpreted. She then asks the audience to write a question that they still have about this research on note cards, which she collects and reviews after the presentation. After reviewing the cards, she decides to incorporate a little more explanation about a few graphs in her work to help future audiences digest the information.

Situation: Antonio Villarreal is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, who has recently been selected for a 15-minute presentation in the Endocytic Trafficking Minisymposium at the American Society for Cell Biology Annual Meeting. He has attended this conference twice, so he has a sense of the audience, space, and culture of the meeting. In his past experiences, he has found that the talks often blur together, and it is especially difficult to remember key ideas from the later talks in each session.

Presentation Goals: With a manuscript in preparation and his upcoming search for a faculty position, Antonio has the following three goals for his presentation: 1) to highlight the significance of his research in a memorable way; 2) to keep the audience engaged, because his presentation is the ninth out of 10 talks; and 3) to receive feedback that will prepare him to give professional job talks.

Scientific Presenting Strategy: Antonio took a class as a postdoctoral fellow about evidence-based practices in teaching and decides he would like to incorporate some active learning into his talk to help his audience learn. He worries that with only 15 minutes he does not have a lot of time to spare. So he sets up the background and experimental design for the audience and then projects only the two axes of his most impactful graph on the screen with a question mark in the middle where the data would be. Rather than simply showing the result, he asks the audience to turn to a neighbor and make a prediction about the results they expect to see. He cues the audience to talk to one another by encouraging them to make a bold prediction! After 30 seconds, he quells the chatter and highlights two different predictions he heard from audience members before sharing the results. At the end of his presentation, he asks the audience to turn to a neighbor once again and discuss what the results mean and what experiment they would try next. He also invites them to talk further with him after the session. The questions Antonio receives after his talk are very interesting and help him consider alternative angles he could pursue or discuss during future talks. He also asks his colleague Jenna to record his talk on his iPhone, and he reviews this recording after the session to prepare him for the job market.

SCIENTIFIC PRESENTING: USING A SCIENTIFIC TEACHING PERSPECTIVE TO DESIGN CONFERENCE PRESENTATIONS

Presenters, like teachers, often try to help their audiences connect new information with what they already know ( National Research Council, 2000 ). While a conference audience differs from a student audience, evidence and strategies collected from the learning sciences can assist in designing presentations to maximize learning and engagement. We propose that the scientific teaching framework, developed by Handelsman and colleagues (2007) to aid in instructional design, can be used as a tool in developing presentations that promote learning, are inclusive, and allow for the collection of useful feedback. In this section, we discuss the three pillars of scientific teaching: active learning, diversity, and assessment. We outline how they can be used to address the central challenges outlined earlier and provide specific tips and strategies for applying scientific teaching in a conference setting.

Challenge: Engagement in Learning

Consider the last conference you attended: How engaged were you in the presentations? How many times did you check your phone or email? How much did you learn from the talks you attended? Professional communities are calling for more compelling presentations that convey information successfully to a broad audience (e.g., Carlson and Burdsall, 2014 ; Langin, 2017 ). Active-learning strategies, when combined with constructivist approaches, are one way to increase engagement, learning, and retention ( Prince, 2004 ; Freeman et al. , 2014 ). While active-learning strategies are not mutually exclusive with the use of PowerPoint presentations in the dissemination of information, they do require thoughtful design, time for reflection, and interaction to achieve deeper levels of learning ( Chi and Wylie, 2014 ). This may be as simple as allowing 30–60 seconds for prediction or discussion in a 15-minute talk. On the basis of calls for change from conference goers and organizers and research on active-learning techniques, we have identified several potential benefits of active learning likely to enhance engagement in conference presentations:

Active learning increases engagement and enthusiasm. Active learning allows learners to maintain focus and enthusiasm throughout a learning experience (e.g., Michael, 2006 ). Use of active learning may particularly benefit audience members attending long presentations or sessions with back-to-back presenters.

Active learning improves retention of information. Active reflection and discussion with peers supports incorporation of information into one’s own mental models and creates the connections required for long-term retention of information (reviewed in Prince, 2004 ).

Active learning allows for increased idea exchange among participants. Collaborative discourse among individuals with differing views enhances learning, promotes argumentation, and allows construction of new knowledge ( Osborne, 2010 ). Active-learning approaches foster idea exchange and encourage interaction, allowing audience members to hear various perspectives from more individuals.

Active learning increases opportunities to build relationships and expand networks. Professional networking is important for expansion of professional communities, enhancing collaborations, and fostering idea exchange. Short collaborative activities during presentations can be leveraged to build social networks and foster community in a professional setting, similar to how they are used in instruction ( Kember and Leung, 2005 ; Kuh et al ., 2006 ).

While a multitude of ways to execute active learning exist, we offer a few specific suggestions to quickly engage the audience during a conference presentation ( Table 1 ). In the spirit of backward design, we encourage you to identify learning activities that support attainment of your presentation goals. Some examples can be found in Vignettes 1 and 2 (section 1), which illustrate hypothetical scenarios in which active learning is incorporated into presentations at professional conferences to help meet specific goals.

Active-learning strategies for conference presentations

Similar to giving a practice talk before the conference, we encourage you to test out active-learning strategies in advance, particularly if you plan to incorporate technology, because technological problems can result in disengagement ( Hatch et al ., 2005 ). Practicing presentation activities within a research group or local community will provide guidance on prompts, timing, instructions, and audience interpretation to identify problems and solutions before they occur during a presentation. This will help to avoid activities that are overly complex or not purpose driven ( Andrew et al ., 2011 ).

Challenge: Equity and Participation

Consider the last conference you attended: Did you hear differing opinions about your work or did the dominant paradigms prevail? Who asked questions; was it only high-status experts in the field? Did you hear from multiple voices? Did newer members, like graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, engage with established members of the community? In classroom settings, equity and diversity strategies improve learning among all students and particularly support students from underrepresented groups in science by decreasing feelings of exclusion, alleviating anxiety, and counteracting stereotype threat ( Haak et al ., 2011 ; Walton et al ., 2012 ; Eddy and Hogan, 2014 ). Likewise, in a conference setting, strategies that promote equitable participation and recognize the positive impact of diversity in the field may help increase equity more broadly and promote a sense of belonging among participants. Conference audiences are oftentimes even more diverse than the typical classroom environment, being composed of individuals from different disciplines, career stages, and cultures. Incorporating strategies that increase the audience’s understanding and feelings of inclusion in the professional community may impact whether or not an individual continues to engage in the field. We have identified three central benefits of equity strategies for presenters and their professional communities:

Equity strategies increase accessibility and learning. As a presenter, you should ensure that presentations and presentation materials 1) allow information to be accessed in various forms, so that differently abled individuals may participate fully, and 2) use straightforward language and representations. You can incorporate accessible versions of conference materials (e.g., captioned videos) or additional resources, such as definitions of commonly used jargon necessary to the presentation (e.g., Miller and Tanner, 2015 ). You may consider defining jargon or acronyms in your talk to increase accessibility for individuals who might struggle to understand the full meaning (e.g., new language learners or individuals who are new to the field).

Equity strategies support inclusion of diverse views and priorities. Creating space for individuals from different backgrounds to express views on a topic supports critical evaluation of ideas and paradigms within a community and prevents members of the community from developing myopic or one-sided views on a subject. This helps to increase creative efforts and enhance new ideas that drive a community forward and sustain its growth ( Richard and Shelor, 2002 ; Bassett-Jones, 2005 ). Furthermore, welcoming individuals from all backgrounds allows us to address relevant priorities for more populations and thus for our work to serve more communities ( Hacker, 2013 ). These strategies can be accomplished by creating space for more individuals to participate in active-learning or question-and-answer sessions (e.g., asking for more hands; Table 2 ) or by deliberately using inclusive language as is recommended when teaching nonnative language learners ( Motschenbacher, 2017 ) or serving patients in healthcare (e.g., Rossi and Lopez, 2017 ).

Equity strategies promote a sense of belonging among all individuals. Creating a welcoming, inclusive environment will make the community attractive to new members and help to increase community members’ sense of belonging. Sense of belonging helps individuals in a community to view themselves as valued and important, which serves to motivate these individuals toward productive action. This increases positive affect, boosts overall community morale, and supports community development ( Winter-Collins and McDaniel, 2000 ). Belonging can increase if it is specifically emphasized as important and if individuals make personal connections to others, such as during small-group work (see Table 2 ).

Equity strategies for conference presentations (as presented in Tanner, 2013 )

Many strategies discussed in prior sections, such as using active learning and having clear goals, help to promote equity, belonging, and access. In Table 2 , we expand on previously mentioned strategies and discuss how specific active-learning and equity strategies promote inclusiveness. These tips for facilitation are primarily drawn from Tanner’s 2013 feature on classroom structure, though they apply to the conference presentation setting as well.

An overarching goal of conferences is to help build a thriving, creative, inclusive, and accessible community. Being transparent about which equity strategies you are using and why you are using them may help to promote buy-in and encourage others to use similar strategies. By taking the above actions as presenters and being deliberate in our incorporation of equity and diversity strategies, we can help our professional communities to thrive, innovate, and grow.

Challenge: Receiving Feedback

Consider your last conference presentation: What did you take away from the presentation? Did you gather good ideas during the session? Were the questions and comments you received useful for advancing your work? If you were to present this work again, what changes might you make? In the classroom, assessment drives learning of content, concepts, and skills. At conferences, we, as presenters, take the role of instructor in teaching our peers (including members of our research field) about new findings and innovations. However, assessment at conferences differs from classroom assessment in important ways. First, at conferences, you are unlikely to present to the same audience multiple times; therefore, the focus of the assessment is purely formative—to determine whether the presentation accomplished its goals. This feedback can aid in your professional development toward being an effective communicator. Second, at conferences, you are speaking to a diverse group of colleagues who have varied expertise, and feedback from the audience will provide information that may improve your research. Indeed, conferences are a prime environment to draw on a diversity of expertise to identify relevant information, resources, and alternative interpretations of data. These characteristics of conferences give rise to three possible types of presentation assessments ( Hattie and Timperley, 2007 ):

Feed-up: assessment of the achievement of presentation goals: Did I achieve my goals as a presenter?

Feed-back: assessment of whether progress toward project goals is being achieved: Is my disciplinary work or research progressing effectively?

Feed-forward: input on which activities should be undertaken next: What are the most important next steps in this work for myself and my professional community?

Though a lot of feedback at conferences occurs in informal settings, you can take the initiative to incorporate assessment strategies into your presentation. Many of the simple classroom techniques described in the preceding sections, like polling the audience and hearing from multiple voices, support quick assessment of presentation outcomes ( Angelo and Cross, 1993 ). In Table 3 , we elaborate on possible assessment strategies and provide tips for gathering effective feedback during presentations.

Assessment and feedback strategies for conference presentations

a We suggest these questions for a simple, yet informative postpresentation feed-up survey about your presentation: What did you find most interesting about this presentation? What, if anything, was unclear or were you confused about (a.k.a. muddiest point)? What is one thing that would improve this presentation? Similarly, to gather information for a feedback/feed-forward assessment, we recommend: What did you find most interesting about this work? What about this project needs improvement or clarification? What do you consider an important next step that this work might take?

Technology can assist in implementing assessment, and we predict that there will be many future technological innovations applicable to the conference setting. Live tweeting or backchanneling is occurring more frequently alongside presentations, with specific hashtags that allow audience members to initiate discussions and generate responses from people who are not even in the room ( Wilkinson et al ., 2015 ). After the presentation, you and your audience members can continue to share feedback and materials through email list servers and QR codes. Self-assessment by reviewing a video from the session can support both a better understanding of audience engagement and self-reflection ( van Ginkel et al ., 2015 ). There are benefits from gathering data from multiple assessment strategies, but as we will discuss in the next section, there are barriers that impact the number of recommended learning, equity, and assessment strategies you might chose to implement.

NAVIGATING BARRIERS TO SCIENTIFIC PRESENTING

Though we are strong advocates for a scientific presenting approach, there are several important barriers to consider. These challenges are similar to what is faced in the classroom, including time, space, professional culture, and audience/student expectations.

One of the most important barriers to consider is culture, as reflected in the following quote:

Ironically, the oral presentations are almost always presented as lectures, even when the topic of the talk is about how lecturing is not very effective! This illustrates how prevalent and influential the assumptions are about the expected norms of behavior and interaction at a scientific conference. Even biologists who have strong teaching identities and are well aware of more effective ways to present findings choose, for whatever reason (professional culture? professional identity?), not to employ evidence-based teaching and communication methods in the venue of a scientific conference. ( Brownell and Tanner, 2012 , p. 344)

As this quote suggests, professional identity and power structures exist within conference settings that may impact the use of scientific presenting strategies. Trainees early in their careers will be impacted by disciplinary conference norms and advisor expectations and should discuss incorporating new strategies with a trusted mentor. In addition, incorporating scientific presenting strategies can decrease your control as a presenter and may even invoke discomfort and threaten your or your audience’s professional identities.

Balance between content delivery and active engagement presents another potential barrier. Some may be concerned that active learning takes time away from content delivery or that using inclusive practices compromises the clarity of a central message. Indeed, there is a trade-off between content and activity, and presenters have to balance presenting more results with time spent on active learning that allows the audience to interpret the results. We suggest that many of these difficulties can be solved by focusing on your goals and audience background, which will allow you to identify which content is critical and hone your presentation messaging to offer the maximum benefit to the audience. Remember that coverage of content does not ensure learning or understanding and that you can always refer the audience to additional content or clarifying materials by providing handouts or distributing weblinks to help them engage as independent learners.

Physical space and time may limit participants’ interaction with you and one another. Try to view your presentation space in advance and consider how you will work within and possibly modify that space. For example, if you will present in a traditional lecture hall, choose active learning that can be completed by an individual or pairs instead of a group. By being aware of the timing, place in the conference program, and space allotted, you can identify appropriate activities and strategies that will fit your presentation and have a high impact. Available technology, support, and resources will also impact the activities and assessments you can implement and may alleviate some space and time challenges.

As novice scientific presenters dealing with the above barriers and challenges, “failures” or less than ideal attempts at scientific presenting are bound to occur. The important thing to remember is that presenting is a scientific process, and just as experiments rarely work perfectly the first time they are executed, so too does presenting in a new and exciting way. Just as in science, challenges and barriers can be overcome with time, iterations, and thoughtful reflection.

STRUCTURING A CONFERENCE TO FACILITATE SCIENTIFIC PRESENTING

Although presenters can opt to use backward design and incorporate scientific presenting strategies, they do not control other variables like the amount of time allotted to each speaker, the size or shape of the room they present in, or the technology available. These additional constraints are still important and may impact a presenter’s ability to use audience-centered presentation methods. Conference organizers are in a powerful position to support presenters’ ability to implement the described strategies and to provide the necessary logistical support to maximize the likelihood of success. Organizers often set topics, determine the schedule, book spaces, identify presenters, and help establish conference culture.

So how can conference organizers affect change that will promote active engagement and equity in conference presentations?

Use backward design for the conference as a whole. Just as presenters can use backward design to set their specific learning goals, conference organizers can set goals for the meeting as a whole to support the conference community.

Vary conference structures and formats based on the needs of the community. Conference presentation structures vary widely, but it is worth considering why certain session structures are used. To what extent does it serve the community to have back-to-back 10-minute talks for several hours? Many people will have the chance to present, but does the audience gain anything? Are there topics that would be better presented in a workshop format or a roundtable discussion? What other structures might benefit the conference community and their goals?

Choose a space that is conducive to active presentations or consider creative ways to use existing spaces. The spaces available for conferences are typically designed for lecture formats. However, organizers can seek out spaces that facilitate active presenting by choosing rooms with adaptable formats in which furniture can be moved to facilitate small-group discussions. They can also provide tips on how to work within existing spaces, such as encouraging participants to sit near the front of a lecture hall or auditorium.

Give explicit expectations to presenters. Organizers could inform presenters that active, engaging, evidence-based sessions are encouraged or expected. This will help cultivate the use of scientific presenting within the community.

Provide examples or support for presenters to aid in design of active learning, equity strategies, and assessment. Videos with examples of the described techniques, a quick reference guide, or access to experts within the field who would be willing to mentor presenters could be critical for supporting a conference culture that uses scientific presenting. For example, researchers at the University of Georgia have developed a repository of active-learning videos and instructions for instructors interested in developing these skills (REALISE—Repository for Envisioning Active-Learning Instruction in Science Education, https://seercenter.uga.edu/ realisevideos_howto ).

Collect evidence about conference structure and use it to inform changes. Surveying audience members and presenters to better understand the benefits and challenges of particular session formats can help inform changes over multiple years. Organizers should coordinate these efforts with presenters so they are aware of what data will be collected and disseminated back to them.

Although scientific teaching has increasingly become standard practice for evidence-based teaching of science courses, there are potentially great benefits for transforming our oral presentations in science and science education by incorporating the rigor, critical thinking, and experimentation that are regularly employed within research. The strategies suggested in this paper can serve as a starting point for experimentation and evaluation of presentation and conference efficacy. Using scientific presentation strategies may expedite the advancement of fields by increasing engagement and learning at conference presentations. Equity strategies can increase inclusion and community building among members of our research areas, which will help research fields to grow and diversify. Finally, regularly incorporating assessment into our presentations should improve the quality and trajectory of research projects, further strengthening the field. Both individual presenters and conference organizers have a role to play in shifting conference culture to tackle the challenges presented in this paper. We urge you to consider your role in taking action.

Acknowledgments

We thank Justin Hines, Jenny Knight, and Kimberly Tanner for thoughtful suggestions on early drafts of this article.

- Andrew T. M., Leonard M. J., Colgrove C. A., Kalinowski S. T. (2011). Active learning not associated with student learning in a random sample of college biology courses. CBE—Life Sciences Education , (4), 394–405. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Angelo T. A., Cross K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bassett-Jones N. (2005). The paradox of diversity management, creativity and innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management , (2), 169–175. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brownell S. E., Tanner K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and … tensions with professional identity. CBE—Life Sciences Education , (4), 339–346. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlson M., Burdsall T. (2014). In-progress sessions create a more inclusive and engaging regional conference. American Sociologist , , 177. 10.1007/s12108-014-9220-2 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chi M. T. H., Wylie R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist , (4), 219–243. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eddy S. L., Hogan K. A. (2014). Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work. CBE—Life Sciences Education , (3), 453–468. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman S., Eddy S. L., McDonough M., Smith M. K., Okoroafor N., Jordt H., Wenderoth M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA , (23), 8410–8415. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haak D. C., HilleRisLambers J., Pitre E., Freeman S. (2011). Increased structure and active learning reduce the achievement gap in introductory biology. Science , (6034), 1213–1216. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hacker K. (2013). Community-based participatory research . Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Handelsman J., Miller S., Pfund C. (2007). Scientific teaching . New York: Macmillan. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hatch J., Jensen M., Moore R. (2005). Manna from heaven or clickers from hell. Journal of College Science Teaching , (7), 36 [ Google Scholar ]

- Hattie J., Timperley H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research , (1), 81–112. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kember D., Leung D. Y. (2005). The influence of active learning experiences on the development of graduate capabilities. Studies in Higher Education , (2), 155–170. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuh G., Kinzie J., Buckley J., Bridges B. K., Hayek J. C. (2006). What matters to student success: A review of the literature (Commissioned Report for the National Symposium on Postsecondary Student Success: Spearheading a Dialog on Student Success . Retrieved July 3, 2017, from https://nces.ed.gov/npec/pdf/kuh_team_report.pdf .

- Langin K. M. (2017). Tell me a story! A plea for more compelling conference presentations. The Condor , (2), 321–326. [ Google Scholar ]

- McTighe J., Thomas R. S. (2003). Backward design for forward action. Educational Leadership , (5), 52–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Michael J. (2006). Where’s the evidence that active learning works. Advances in Physiology Education , (4), 159–167. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller S., Tanner K. D. (2015). A portal into biology education: An annotated list of commonly encountered terms. CBE—Life Sciences Education , (2), fe2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Motschenbacher H. (2017). Inclusion and foreign language education. ITL—International Journal of Applied Linguistics , (2), 159–189. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Research Council. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school . (expanded ed.). Washington, DC: National Academies Press; https://doi.org/10.17226/9853 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Osborne J. (2010). Arguing to learn in science: The role of collaborative, critical discourse. Science , (5977), 463–466. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prince M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education , (3), 223–231. [ Google Scholar ]

- Richard O. C., Shelor R. M. (2002). Linking top management team age heterogeneity to firm performance: Juxtaposing two mid-range theories. International Journal of Human Resource Management , (6), 958–974. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rossi A. L., Lopez E. J. (2017). Contextualizing competence: Language and LGBT-based competency in health care. Journal of Homosexuality , (10), 1330–1349. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tanner K. D. (2013). Structure matters: Twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity. CBE—Life Sciences Education , (3), 322–331. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van Ginkel S., Gulikers J., Biemans H., Mulder M. (2015). Towards a set of design principles for developing oral presentation competence: A synthesis of research in higher education. Educational Research Review , , 62–80. [ Google Scholar ]

- Walton G. M., Cohen G. L., Cwir D., Spencer S. J. (2012). Mere belonging: The power of social connections. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , (3), 513. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilkinson S. E., Basto M. Y., Perovic G., Lawrentschuk M., Murphy D. G. (2015). The social media revolution is changing the conference experience: Analytics and trends from eight international meetings. BJU International , (5), 839–846. 10.1111/bju.12910 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Winter-Collins A., McDaniel A. M. (2000). Sense of belonging and new graduate job satisfaction. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development , (3), 103–111. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (212.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload