An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J R Soc Med

- v.102(1); 2009 Jan 1

Kidnapping and hostage-taking: a review of effects, coping and resilience

Introduction.

Although the history of kidnapping and hostage-taking is a very long one, it is only relatively recently that there has been a systematic attempt to understand the effects, both long-term and short-term, on individuals and their families. This is an important issue for clinical and academic reasons. The advice of mental health professionals is sought with increasing frequency with regard to the strategic management of hostage incidents and the clinical management of those who have been abducted. There is evidence to suggest that how best to help those who have been taken hostage is a sensitive and complex matter, and those who deal with such individuals should be as well informed as possible since such events can have long-term adverse consequences, particularly on young children.

This paper addresses the following:

- the background in terms of the history of this phenomenon, the motives behind it and the authorities' responses thereto;

- the psychological and physical effects of being taken hostage;

- coping and survival strategies;

- issues which require further research.

Early texts refer to the kidnapping of Abram's nephew (Lot), Julius Caesar and Richard the Lionheart. In medieval times, knights displayed their noble heritage through heraldic devices in the hope that their higher perceived market value would increase their chances of being kept alive for ransom rather than being killed. In the 17th century, children were stolen from their families for ‘export’ to the North American colonies as servants and labourers. (Hence, ‘kid’ meaning ‘child’, and ‘nap’ or ‘nab’ meaning ‘to snatch’.) Press-ganging was a means of ensuring an adequate supply of personnel for the merchant fleet during the 19th century.

Certain high profile events, much due to the efforts of the media, highlighted the psychological impact of kidnapping. For example, one of the earliest was the kidnapping on 1 March 1932 by Bruno Hauptmann, a German carpenter, of Colonel Charles Lindbergh's son for ransom. 1 The suffering of the child's parents, and the difficulties of the police enquiry, were exacerbated by widespread speculation and misinformation, and serial random notes. The mutilated body of the child was found and the perpetrator was executed on 3 April 1936. This event caused public revulsion, and the revision of the authorities' bargaining and investigating methods, particularly by the FBI, and even the suicide of a waitress to the family, who was cleared in the enquiries.

In 1972, the ‘Black September’ group (an auxiliary faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation) took hostage the Israeli wrestling team at the Munich Olympics. The unsuccessful negotiations, and the tragic deaths of the whole team during an abortive rescue effort by the German Border Police, were relayed throughout the world by the international media. 2 Also, after this tragedy, many international authorities revised their strategies for dealing with hostage incidents and sieges.

Motives for taking hostages

Motives can be divided into ‘expressive’ (i.e. an effort to voice and/or publicize a grievance or express a frustrated emotion) and ‘instrumental’ (i.e. to obtain a particular outcome such as ransom). 3 In reality it is usually difficult to identify any single motive, particularly when the event is terrorist-inspired. Material motives (e.g. ransom) may be conveniently masked by alleged religious, political and moral ones. Moreover, ransoms may be used to fund political and religious activities. Also, some insurgency groups sell hostages on to other groups for their own purposes.

The taking of foreign hostages has become a particularly popular modus operandi for terrorists (who tend to be well-organized and selective in their ‘target’ hostages), particularly due to their cynical but generally effective use of extensive media coverage. Also, the frequency of kidnapping of overseas personnel has markedly increased in Afghanistan since the US invasion in 2001. Unfortunately, the death toll among hostages is high in Afghanistan and Iraq. A particularly distasteful feature of hostage-taking in these countries is the video-taped executions of hostages, such as those of Nick Berg (a US businessman) and Ronald Schultz (a US security consultant), and their broadcast by Al Jazeera or Al Arabia: such broadcasts represent, however, a powerful psychological weapon, which, as indicated by Pape, 4 runs the risk of losing public support and sympathy.

Other areas which have become high-risk ones for hostage-taking are Nigeria and Colombia. Most incidents in the former are carried out by criminal gangs for ransom, such as the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta – MEND. Ransoms in both countries are often on a modest scale to ensure they can be paid. This strategy is sometimes referred to as ‘Express Kidnapping’. The frequency of hostage incidents in Colombia has increased 1600% between 1987 and 2000. 5 The motives there appear to be largely criminal, for financial gain, rather than political. Sometimes such events are described as ‘Economic Extortive Kidnapping’. These events can have demoralizing effects on families, who may lose all faith in supportive agencies and organizations, according to a follow-up study by Navia and Ossa. 5

Authorities' responses

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the prevailing model of dealing with such incidents, particularly in the prisons of the USA, had been the ‘Suppression Model’ (i.e. the use of overwhelming physical force). 6 This approach can still be used successfully as was shown by the interventions of the Special Air Service in response to the Iranian Embassy Siege in 1980 in London. However, such successes are not common, and they require extremely careful planning and execution. Armed response has now generally yielded to the techniques of negotiation and conflict resolution in recognition of the risks that an armed response creates for hostages. Such risks were tragically demonstrated at the 1972 Munich Olympics. 2 More recently, the catastrophic failures by the Russian authorities to rescue the patrons of the Dubrovka theatre in Moscow in 2002 and the children and staff of the Beslan school in 2004, confirmed how risky armed intervention by the authorities can be. The last two incidents resulted in the deaths of 130 and 334 hostages, respectively.

From a psychological point of view, negotiation ‘buys time’ to enable:

- hostages, perpetrators and the authorities to ‘cool down’;

- the authorities to clarify the motives of the perpetrator(s);

- the authorities to gather intelligence;

- the authorities to formulate a rescue strategy (should negotiation fail).

Unfortunately, from the hostages' point of view progress may seem to be very slow, and they commonly wonder why the authorities do not ‘do something’, including effecting their rescue by force.

Psychological and physical effects of being a hostage

For ethical and practical reasons, particularly if children are involved, the follow-up of hostages on release is difficult. 7 Thus, the scientific and clinical database is relatively modest. Much reliance is therefore placed on autobiographical and biographical accounts of high profile hostages (e.g. Waite, 8 Slater, 9 Keenan 10 and Shaw 11 ).

Psychological effects

In general terms, the psychological impact of being taken hostage is similar to that of being exposed to other trauma, including terrorist incidents and disasters for adults 12 and children. 13

Typical adult reactions include:

- Cognitive : impaired memory and concentration; confusion and disorientation; intrusive thoughts (‘flashbacks’) and memories; denial (i.e. that the event has happened); hypervigilance and hyperarousal (a state of feeling too aroused, with a profound fear of another incident);

- Emotional : shock and numbness; fear and anxiety (but panic is not common); 14 helplessness and hopelessness; dissociation (feeling numb and ‘switched off’ emotionally); anger (at anybody – perpetrators, themselves and the authorities); anhedonia (loss of pleasure in doing that which was previously pleasurable); depression (a reaction to loss); guilt (e.g. at having survived if others died, and for being taken hostage);

- Social : withdrawal; irritability; avoidance (of reminders of the event).

Denial (i.e. a complete or partial failure to acknowledge what has really happened) has often been maligned as a response to extreme stress, but it has survival value (at least in the short term) by allowing the individual a delayed period during which he/she has time to adjust to a painful reality. For example, some hostages in the Moscow theatre siege initially believed that the appearance of the heavily armed Chechnyan rebels was part of the military musical performance. 15

Two extreme reactions have also been noted, namely, ‘frozen fright’ and ‘psychological infantilism’. 16 The former refers to a paralysis of the normal emotional reactivity of the individual, and the latter reaction is characterized by regressed behaviour such as clinging and excessive dependence on the captors.

Extended periods of captivity may also lead to ‘learned helplessness’ 17 in which individuals come to believe that no matter what they do to improve their circumstances, nothing is effective. This is reminiscent of the automaton-like state reported by concentration camp victims (‘walking corpses’). 18

Genuine psychopathology has also been noted. A follow-up study of ransom victims in Sardinia found that about 50% suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and about 30% experienced major depression. 19 The International Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (ICD-10) 20 also recognizes the ‘Enduring personality change after a catastrophic experience’ (F62.0) as a possible chronic outcome after a hostage incident. This condition is characterized by:

- a hostile or mistrustful attitude;

- social withdrawal and estrangement;

- feelings of emptiness or hopelessness;

- a chronic feeling of being ‘on edge’ as if constantly threatened.

For the diagnosis to be made the symptoms must have endured for at least two years.

The severe and sustained impact on children is demonstrated by several abductions, including that of the children involved in the Chowchilla incident in San Francisco. Terr 21 confirmed, after that incident (in which 26 children and their driver were abducted and held in a vehicle underground) all the children displayed signs of PTSD, and some symptoms worsened over time (e.g. shame, pessimism and ‘death dreams’).

Denial, ‘frozen fright’, ‘psychological infantilism’ and ‘learned helplessness’ are not age-specific. Children may also display: school refusal, loss of interest in studies, dependent and regressed behaviour, preoccupation with the event, playing at being the ‘rescuer’, stubborn and oppositional behaviour, and risk-taking. The impact can be particularly serious if the children have been detained over an extended period and if the incident entailed a breach of trust. 22

Physical effects

Hostages are likely to have to endure, particularly during sustained periods of captivity, an exacerbation of pre-existent physical conditions, such as asthma and diabetes. Also, the detention itself may generate new conditions due to a lack of the basics of healthy living, such as a nutritious diet, warmth, exercise, fresh air and sleep.

At-risk and resilience factors

As yet there is no clear delineation of all factors which conduce to an adverse outcome following being taken hostage. However, there is evidence that women (especially younger women), more than men, are at risk of such an outcome, as are those of low educational level, and those exposed to an extended period of captivity. 23 An extensive review 24 also suggests that the following may contribute to a poorer post-release adjustment: passive-dependent traits; a belief that one's fate is exclusively in the hands of others; and a dogmatic-authoritarian attitude. Among children, younger age and pre-existent family problems, 15 and the loss of education and the need for post-incident medical care 25 may also contribute to adjustment problems.

In recent years, there has been a move in the trauma field from a ‘pathogenic’ model (which emphasizes illness and problems of adjustment) to a ‘resilience’ model (which emphasizes coping and ‘personal growth’ through adversity). While there are uncertainties as to how best to define and measure resilience, this perspective offers a more positive and optimistic approach. Certainly, it is worth emphasizing that many survivors do appear to cope over time, particularly if their family and social environment is supportive. Moreover, a number of high profile hostages (e.g. Terry Waite 8 ) have demonstrated how they have used their experiences constructively after their release. Adopting a ‘resilience’ approach to this kind of trauma may also enhance our understanding the best coping strategies for hostages during their captivity, and for the development of better post-incident care management for them.

Coping and survival strategies

Although it is usually regarded as an ‘effect’ of being taken hostage, the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ will be regarded here as a means of coping and surviving since it certainly enables, on many occasions, hostages to deal with extreme and life-threatening circumstances. The term was first coined by criminologist, Nils Bejerot, to describe the unexpected reactions of hostages both during and after an armed bank raid in Sweden in 1973. 26 It was noted that, despite being subject to a life-threatening situation by the raiders, the hostages (three women and one man) forged positive relationships with their captors even to the point of helping to finance their defence after their apprehension. Conversely, the hostage-takers began to bond with their captives. This paradoxical reaction has been noted in many other incidents. The 10-year-old girl, Natascha Kampusch, who was held captive for eight years bonded with her abductor to such an extent that, on his suicide immediately after her escape, she blamed the police for his death and clearly grieved his death. 27

It is not clear why some individuals react in this fashion while others do not. Some merely seek to escape. For example, in Georgia, Peter Shaw, a British financial adviser, was detained in freezing underground conditions and regularly beaten. Fearing his imminent execution, he courageously sought escape. Others maintain hostility to their captors and refusal to accede to requests to convert to Islam (e.g. Yvonne Ridley, 28 a British journalist held for 11 days by the Taliban). However, certain conditions do increase the likelihood of the Stockholm reaction. These include:

- an extended and emotionally charged environment;

- an adverse environment shared by hostages and hostage-takers (e.g. poor diet and physical discomfort);

- when threats to life are not carried out (e.g. ‘mock executions’);

- when there has to be a marked dependence by the hostages on the hostage-takers for even the most basic needs;

- when there are opportunities for bonding between captives and their captors in circumstances in which the former have not been ‘dehumanized’. (Some hostage-takers aim to dehumanize hostages by hooding them, depriving them of their names, any identifying details and possessions, treating them as ‘animals’ and changing regularly their guards – as did Saddam Hussein with his ‘human shields’ in Kuwait.)

The disadvantages of this reaction are that the hostages after the incident may feel guilty and embarrassed about the way they have reacted. It means that the authorities cannot totally rely on hostages for accurate intelligence or expect them to contribute to any escape plan.

Although PTSD and the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ reaction both reflect the severity of the experience, the former is more related to the level of physical violence displayed towards the hostage, whereas the latter reaction is correlated with the level of humiliation and deprivation. 21 For some individuals it may represent their hope for escape or a way of achieving a psychological separation between their previous ‘normal’ way of life and their new circumstances. The validity of the concept has been challenged by Namnyak et al. , 26 and they suggest that its features lack rigorous empirical evaluation, as well as validated diagnostic criteria, but owes much to the bias of personal and media reporting. Others, for example Cantor and Price, 29 view this concept through the prism of evolutionary theory in a fashion which casts light on this phenomenon as well as on other unequal power relationships, including ‘boy soldiers’ and their leaders, abused children and their parents, and cases of complex PTSD.

Other individual methods of coping with extended captivity include: use of distraction (e.g. mental arithmetic, reading and fantasy); regular discipline (e.g. with regard to personal hygiene and exercise); taking one day at a time; and trying to find something positive in the situation (e.g. Terry Waite 8 began preparing in his mind his autobiography). Jacobsen describes how a group of adolescents, following a skyjacking, viewed their experience initially with a sense of excitement and adventure and were particularly helpful to young mothers with children on the aircraft. 30

Issues which require further research

There are extensive but important gaps in the literature. For example, in relation to attachment theory, it is not clear whether children in particular are affected principally by the emotional stimulation or drive reduction, as the Stockholm Syndrome develops. What underpins this bonding, for different individuals in different crises, has yet to be determined. It is also unclear to what extent the apparent motives of the perpetrators influences the bonding between captor and captive (although it can be difficult to identify the true motives of, for example, terrorists who take hostages). We also need to know more about the interaction between terrorists (who characteristically create a ‘public’ event) and other external agencies, such as the authorities and the media, and the terrorists themselves whose motives, level of determination etc may not be identical. 31 With regard to psychological interventions, particularly in the case of children, we also lack much clarity.

This is a complex and delicate area of research; perpetrators may be inaccessible or unreliable witnesses, and there is the omnipresent risk of re-traumatizing survivors through rehearsal of deeply disturbing experiences. Our current database is however too narrow to fashion a better understanding of such events and how to devise strategies and associated training to deal with them.

This review is inevitably constrained by word length, and it is confined to articles cast in English. It is not able to address the impact of hostage-taking and kidnapping on the families of the victims or on those, such as therapists and police family liaison officers who have to respond to the psychological aftermath of such incidents. This review has however highlighted key issues relating to the motives underlying crimes of this kind and how individuals cope during them and subsequently react. While survivors of such experiences commonly demonstrate remarkable resilience, there is no doubt that those experiences can produce a legacy of chronic emotional disturbance and compromised relationships.

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests DAA is a part-time police consultant, paid by honorarium to the Robert Gordon University, and an unpaid trainer in hostage negotiation at the Scottish Police College

Funding None

Ethical approval Not applicable

Guarantor DAA

Contributorship Both authors contributed equally with regard to the literature search and the drafting of the article

Acknowledgements

Articles on Kidnapping

Displaying 1 - 20 of 30 articles.

Bri Lee’s and Louise Milligan’s predictable first novels combine noughties feminist politics with the swagger of 80s bonkbusters

Liz Evans , University of Tasmania

Kidnapping in Nigeria: criminalising ransom payment isn’t working - families need support

Oludayo Tade , University of Ibadan

Finding Ukraine’s stolen children and bringing perpetrators to justice: lessons from Argentina

Francesca Lessa , University of Oxford and Svitlana Chernykh , Australian National University

Jihadists and bandits are cooperating. Why this is bad news for Nigeria

Folahanmi Aina , Royal United Services Institute

4 plays that dramatize the kidnapping of children during wars

Magda Romanska , Emerson College

Why Nigerian kidnap law banning families from paying ransoms may do more harm than good

Ayoade Onireti , University of Salford

Conviction of two Michigan kidnap plotters highlights danger of violent conspiracies to US democracy

Amy Cooter , Middlebury

Nigeria’s spiralling insecurity: five essential reads

Adejuwon Soyinka , The Conversation

Who’s at risk of being kidnapped in Nigeria?

Al Chukwuma Okoli , Federal University Lafia

Russia’s reported abduction of Ukrainian children echoes other genocidal policies, including US history of kidnapping Native American children

Marcia Zug , University of South Carolina

Rising vigilantism: South Africa is reaping the fruits of misrule

Loren B Landau , University of the Witwatersrand and Jean Pierre Misago , University of the Witwatersrand

Military postings put strains on Nigerian families: here’s what some told us

Rethinking ukuthwala, the South African ‘bride abduction’ custom

Nyasha Karimakwenda , University of Cape Town

Nigeria: why do children keep getting kidnapped? – podcast

Gemma Ware , The Conversation and Wale Fatade , The Conversation

Nigeria has a new police chief. Here’s an agenda for him

Lanre Ikuteyijo , Obafemi Awolowo University

Why children are prime targets of armed groups in northern Nigeria

Hakeem Onapajo , Nile University of Nigeria

Attacks at sea aren’t all linked to piracy. Why it’s important to unpick what’s what

Dirk Siebels , University of Greenwich

Lessons from embedding with the Michigan militia – 5 questions answered about the group allegedly plotting to kidnap a governor

Amy Cooter , Vanderbilt University

Fighting piracy in the Gulf of Guinea needs a radical rethink

Humanitarian forensic scientists trace the missing, identify the dead and comfort the living

Ahmad Samarji , Phoenicia University and Dina Shokry , Cairo University

Related Topics

- Nigeria kidnapping

- Peacebuilding

Top contributors

Reader (Associate Professor) Department of Political Science, Federal University of Lafia, Nigeria, Federal University Lafia

Director of Research, Academic Development, and Innovation at the Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism, Middlebury

Sociologist/Criminologist/Victimologist and Media Communication Expert, University of Ibadan

PhD (Maritime Security), University of Greenwich

Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science and International Relations, Nile University of Nigeria

Reader in Political Economy, King's College London

Emeritus Professor of Private Law, University of Cape Town

Senior Lecturer in Sociology, Keele University

Associate Professor in International Relations of the Americas, UCL

Lecturer in Visual Anthropology

Professor of Forensic Medicine, Cairo University

Lecturer in Political Economy, SOAS, University of London

Senior lecturer, Ekiti State University

Political Scientist, University of the Western Cape

Head of Research Programme, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Abduction of Children

Introduction, general overviews.

- Offense, Offender, and Victim Characteristics

- Familial Abduction

- Stranger Abduction

- Awareness and Prevention

- AMBER Alert and Other Official Responses

- Social Constructions

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Child Protection

- Child Trafficking and Slavery

- Child Welfare Law in the United States

- Children and Violence

- Divorce and Custody

- History of Childhood in America

- Innocence and Childhood

- Moral Panics

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Agency and Childhood

- Childhood Publics

- Children in Art History

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Abduction of Children by J. Mitchell Miller , Stephanie M. Koskinen LAST REVIEWED: 11 October 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 25 September 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791231-0226

Few crime topics elicit as much fear and concern as child abduction, which is also commonly known as child kidnapping. Child abduction, or kidnapping, is a criminal offense that entails the wrongful taking of a minor by force or violence, manipulation or fraud, or persuasion. There are basically two types of child abduction; familial-parental and the much-exaggerated stranger abductor. Parental abductions are heavily contextualized in child custody and involve far less physical danger to child victims than stranger abductions, which include the majority of violence and sexual violence associated with more extreme abduction events. Despite the popular culture myth of “abduction waves” and pedophiles lurking in the shadows, child abduction is actually a rare phenomenon, as indicated by Shutt, et al. 2004 (cited under Social Constructions ), which likened abduction likelihood to the rarity of a lightning strike. Nonetheless, media hype and sensationalism have framed both popular culture and social-legal constructions of abduction frequency, risk, and offender and victim stereotypes, most notably stranger/pedophile abductors and abduction epidemics. The extant academic literature on child abduction can be observed as a three-pronged typology of 1) historical works, more so accounts of well-known US child kidnappings such as the Lindbergh baby, Adam Walsh, and, more recently, Elizabeth Smart, and international research on abduction for ransom, custody, vice work, and military servitude; 2) legal overviews and opinions, both domestically and internationally, with the latter especially focused on abduction legislation initiatives within Hague Conference; and 3) the focus of this article, empirical scientific works primarily appearing in refereed journal articles. The majority of this literature originates from the behavioral (psychology) and social sciences (criminology and criminal justice, sociology, and political science) and, to a lesser degree, from professional school orientations (social work, nursing, and public health). As a rare event and relatively myopic, though seriously consequential, phenomenon, there isn’t a discernable number of reference works, anthologies, or established published bibliographies informing the child abduction knowledge base. Fortunately, there is a sizeable body of empirical works on child abduction to characterize the nature of the offense, its perpetrator and victim participants, and responses by juvenile and criminal justice as well as other stakeholder agencies. While substantial research attention has addressed child abduction in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Europe, this coverage is based on American research over the last few decades. This empirical literature on child abduction is presented in annotated form as a thematic taxonomy comprised of the following: 1) General Overviews , 2) Offense, Offender, and Victim Characteristics , 3) Familial Abduction , 4) Stranger Abduction , 5) Awareness and Prevention , 6) AMBER Alert and Other Official Responses , and 7) Social Constructions .

Research on child abduction in Boudreaux, et al. 2000 and more recently Walsh, et al. 2016 provides general overviews of the phenomenon. Palmer and Noble 1984 places selective emphasis on incidence rates, motivations, abduction typologies, and historical perspectives, while Heide, et al. 2009 synthesizes the literature on sexually motivated events. These refereed journal articles collectively constitute an empirical overview of child abduction that is enriched by an Oxford University Press book, Fass 1997 , and a technical report, Finkelhor, et al. 1990 , which detail and contextualize the general nature of abduction events.

Boudreaux, M. C., W. D. Lord, and S. E. Etter. “Child Abduction: An Overview of Current and Historical Perspectives.” Child Maltreatment 5.1 (2000): 63–71.

This journal article provides a comprehensive review of empirical literature on child abduction extant at the turn of the 20th century. Major themes include incidence rates, dichotomous operational definition of child abduction (legal/social), victim and offender characteristics, and a motivational typology (maternal longing, sex, retribution, profit, and homicidal intent). Risk factors, victim selection, and evidence-based responses such as child safety training programs and improved investigative practices are also summarized.

Fass, P. S. Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America . New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

This book presents a chronological unfolding of child abduction in the United States. Moving through famous kidnapping cases in American history, from the Ross case (“the crime of the century”) to the Vanderbilt custody abduction and the Lindbergh kidnapping, child abduction is characterized as a rare event exaggerated by the press. Fass presents narrative insight into family life, parenting, and media coverage.

Finkelhor, D., A. Sedlak, and G. T. Hotaling. Missing, Abducted, Runaway, and Thrownaway Children in America: First Report, Numbers and Characteristics National Incidence Studies: Executive Summary. Darby, PA: Diane, 1990.

This report provides a typology of missing and abducted children based on FBI case data. The authors present national estimates in nonfamily and family abduction categories including missing children data on cases where the children have run away or have otherwise gone missing without implication of any crime. The authors urge special attention to and policy focus on high-risk children, who are most likely to be victimized or become perpetrators of crime.

Heide, K. M., E. Beauregard, and W. C. Myers. “Sexually Motivated Child Abduction Murders: Synthesis of the Literature and Case Illustration.” Victims and Offenders 4.1 (2009): 58–75.

This analysis of sexual murders that involve children focuses on offenders who abduct their victims. Offender characteristics are studied, touching on trauma at birth, behavioral issues in childhood, and emotional and physical abuse. The authors suggest that a delay or cessation in personality development may be the root cause for offenders’ actions.

Palmer, C. E., and D. N. Noble. “Child Snatching: Motivations, Mechanisms, and Melodrama.” Journal of Family Issues 5.1 (1984): 27–46.

This article features data from a variety of offender and criminal justice professional interviews. The authors dichotomize motivations for “child snatching” between concern for the child and satisfaction of personal needs. Common factors among child abduction cases are analyzed, such as motivations, planning, hostility, trauma, familial involvement, and agency involvement. The authors recommend extended study of child snatchers and increased involvement by law enforcement.

Walsh, J. A., J. L. Krienert, and C. L. Comens. “Examining 19 Years of Officially Reported Child Abduction Incidents (1995–2013): Employing a Four Category Typology of Abduction.” Criminal Justice Studies 29.1 (2016): 21–39.

This journal article uses NIBRS data to identify child abduction characteristics. Findings suggest that media sensationalism is the cause of misconceptions and an overemphasis on stranger abduction, which are rare in comparison to acquaintance or family abductions.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Childhood Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abduction of Children

- Aboriginal Childhoods

- Addams, Jane

- ADHD, Sociological Perspectives on

- Adolescence and Youth

- Adolescent Consent to Medical Treatment

- Adoption and Fostering

- Adoption and Fostering, History of Cross-Country

- Adoption and Fostering in Canada, History of

- Advertising and Marketing, Psychological Approaches to

- Advertising and Marketing, Sociocultural Approaches to

- Africa, Children and Young People in

- African American Children and Childhood

- After-school Hours and Activities

- Aggression across the Lifespan

- Ancient Near and Middle East, Child Sacrifice in the

- Animals, Children and

- Animations, Comic Books, and Manga

- Anthropology of Childhood

- Archaeology of Childhood

- Ariès, Philippe

- Attachment in Children and Adolescents

- Australia, History of Adoption and Fostering in

- Australian Indigenous Contexts and Childhood Experiences

- Autism, Females and

- Autism, Medical Model Perspectives on

- Autobiography and Childhood

- Benjamin, Walter

- Bereavement

- Best Interest of the Child

- Bioarchaeology of Childhood

- Body, Children and the

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Boy Scouts/Girl Guides

- Boys and Fatherhood

- Breastfeeding

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie

- Bruner, Jerome

- Buddhist Views of Childhood

- Byzantine Childhoods

- Child and Adolescent Anger

- Child Beauty Pageants

- Child Homelessness

- Child Mortality, Historical Perspectives on Infant and

- Child Protection, Children, Neoliberalism, and

- Child Public Health

- Childcare Manuals

- Childhood and Borders

- Childhood and Empire

- Childhood as Discourse

- Childhood, Confucian Views of Children and

- Childhood, Memory and

- Childhood Studies and Leisure Studies

- Childhood Studies in France

- Childhood Studies, Interdisciplinarity in

- Childhood Studies, Posthumanism and

- Childhoods in the United States, Sports and

- Children and Dance

- Children and Film-Making

- Children and Money

- Children and Social Media

- Children and Sport

- Children and Sustainable Cities

- Children as Language Brokers

- Children as Perpetrators of Crime

- Children, Code-switching and

- Children in the Industrial Revolution

- Children with Autism in a Brazilian Context

- Children, Young People, and Architecture

- Children's Humor

- Children’s Museums

- Children’s Parliaments

- Children’s Reading Development and Instruction

- Children's Views of Childhood

- China, Japan, and Korea

- China's One Child Policy

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights Movement and Desegregation

- Classical World, Children in the

- Clothes and Costume, Children’s

- Colonial America, Child Witches in

- Colonialism and Human Rights

- Colonization and Nationalism

- Color Symbolism and Child Development

- Common World Childhoods

- Competitiveness, Children and

- Conceptual Development in Early Childhood

- Congenital Disabilities

- Constructivist Approaches to Childhood

- Consumer Culture, Children and

- Consumption, Child and Teen

- Conversation Analysis and Research with Children

- Critical Approaches to Children’s Work and the Concept of ...

- Cultural psychology and human development

- Debt and Financialization of Childhood

- Discipline and Punishment

- Discrimination

- Disney, Walt

- Divorce And Custody

- Domestic Violence

- Drawings, Children’s

- Early Childhood

- Early Childhood Care and Education, Selected History of

- Eating disorders and obesity

- Education: Learning and Schooling Worldwide

- Environment, Children and the

- Environmental Education and Children

- Ethics in Research with Children

- Europe (including Greece and Rome), Child Sacrifice in

- Evolutionary Studies of Childhood

- Family Meals

- Fandom (Fan Studies)

- Female Genital Cutting

- Feminist New Materialist Approaches to Childhood Studies

- Feral and "Wild" Children

- Fetuses and Embryos

- Films about Children

- Films for Children

- Folk Tales, Fairy Tales and

- Foundlings and Abandoned Children

- Freud, Anna

- Freud, Sigmund

- Friends and Peers: Psychological Perspectives

- Froebel, Friedrich

- Gay and Lesbian Parents

- Gender and Childhood

- Generations, The Concept of

- Geographies, Children's

- Gifted and Talented Children

- Globalization

- Growing Up in the Digital Era

- Hall, G. Stanley

- Happiness in Children

- Hindu Views of Childhood and Child Rearing

- Hispanic Childhoods (U.S.)

- Historical Approaches to Child Witches

- History of Childhood in Canada

- HIV/AIDS, Growing Up with

- Homeschooling

- Humor and Laughter

- Images of Childhood, Adulthood, and Old Age in Children’s ...

- Infancy and Ethnography

- Infant Mortality in a Global Context

- Institutional Care

- Intercultural Learning and Teaching with Children

- Islamic Views of Childhood

- Japan, Childhood in

- Juvenile Detention in the US

- Klein, Melanie

- Labor, Child

- Latin America

- Learning, Language

- Learning to Write

- Legends, Contemporary

- Literary Representations of Childhood

- Literature, Children's

- Love and Care in the Early Years

- Magazines for Teenagers

- Maltreatment, Child

- Maria Montessori

- Marxism and Childhood

- Masculinities/Boyhood

- Material Cultures of Western Childhoods

- Mead, Margaret

- Media, Children in the

- Media Culture, Children's

- Medieval and Anglo-Saxon Childhoods

- Menstruation

- Middle Childhood

- Middle East

- Miscarriage

- Missionaries/Evangelism

- Moral Development

- Multi-culturalism and Education

- Music and Babies

- Nation and Childhood

- Native American and Aboriginal Canadian Childhood

- New Reproductive Technologies and Assisted Conception

- Nursery Rhymes

- Organizations, Nongovernmental

- Parental Gender Preferences, The Social Construction of

- Pediatrics, History of

- Peer Culture

- Perspectives on Boys' Circumcision

- Philosophy and Childhood

- Piaget, Jean

- Politics, Children and

- Postcolonial Childhoods

- Post-Modernism

- Poverty, Rights, and Well-being, Child

- Pre-Colombian Mesoamerica Childhoods

- Premodern China, Conceptions of Childhood in

- Prostitution and Pornography, Child

- Psychoanalysis

- Queer Theory and Childhood

- Race and Ethnicity

- Racism, Children and

- Radio, Children, and Young People

- Readers, Children as

- Refugee and Displaced Children

- Reimagining Early Childhood Education, Reconceptualizing a...

- Relational Ontologies

- Relational Pedagogies

- Rights, Children’s

- Risk and Resilience

- School Shootings

- Sex Education in the United States

- Social and Cultural Capital of Childhood

- Social Habitus in Childhood

- Social Movements, Children's

- Social Policy, Children and

- Socialization and Child Rearing

- Socio-cultural Perspectives on Children's Spirituality

- Sociology of Childhood

- South African Birth to Twenty Project

- South Asia, History of Childhood in

- Special Education

- Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence

- Spock, Benjamin

- Sports and Organized Games

- Street Children

- Street Children And Brazil

- Subcultures

- Teenage Fathers

- Teenage Pregnancy

- The Bible and Children

- The Harms and Prevention of Drugs and Alcohol on Children

- The Spaces of Childhood

- Theater for Children and Young People

- Theories, Pedagogic

- Transgender Children

- Twins and Multiple Births

- Unaccompanied Migrant Children

- United Kingdom, History of Adoption and Fostering in the

- United States, Schooling in the

- Value of Children

- Views of Childhood, Jewish and Christian

- Violence, Children and

- Visual Representations of Childhood

- Voice, Participation, and Agency

- Vygotsky, Lev and His Cultural-historical Approach to Deve...

- Welfare Law in the United States, Child

- Well-Being, Child

- Western Europe and Scandinavia

- Witchcraft in the Contemporary World, Children and

- Work and Apprenticeship, Children's

- Young Carers

- Young Children and Inclusion

- Young Children’s Imagination

- Young Lives

- Young People, Alcohol, and Urban Life

- Young People and Climate Activism

- Young People and Disadvantaged Environments in Affluent Co...

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Parental Kidnapping - Research Issues and Priorities

Additional details, related topics, similar publications.

- Is Dating Aggression Victimization a Risk Factor or a Consequence of Other Forms of Victimization? A Longitudinal Assessment With Latino Youth

- Child Trauma Response Team (CTRT): Social Media Posts

- Associations of exposure to intimate partner violence and parent-to-child aggression with child competence and psychopathology symptoms in two generations

Adjusting to life after being held hostage or kidnapped

Hostage and kidnap survivors can experience stress reactions including denial, impaired memory, shock, numbness, anxiety, guilt, depression, anger, and a sense of helplessness.

- Physical Abuse and Violence

Freedom almost always brings a sense of elation and relief. However, adjusting back to the real world after being held hostage can be just as difficult as abruptly leaving it. Upon release, many hostage survivors are faced with transitioning from conditions of isolation and helplessness to sensory overload and freedom. This transition often results in significant adjustment difficulties.

Hostage and kidnap survivors can experience stress reactions. Typical reactions occur in:

- Thinking: Intrusive thoughts, denial, impaired memory, decreased concentration, being overcautious and aware, confusion, or fear of the event happening again

- Emotions: Shock, numbness, anxiety, guilt, depression, anger, and a sense of helplessness

- Interactions: Withdrawal and avoidance of family, friends, activities, and being on edge

Such reactions to an extremely stressful event are understandable and normal. These are typical responses and generally decrease after a period of time. It is common for people’s reactions to vary from one individual to another.

According to research, hostage survivors often develop an unconscious bond to their captors and experience grief if their captors are harmed. They may also feel guilty for developing a bond. This is typically referred to as the Stockholm syndrome.

Hostage survivors may also have feelings of guilt for surviving while others did not. It is important for survivors to recognize that these are usual human reactions to being held captive.

When hostages are released, it is essential for them to:

- Receive medical attention

- Be in a safe and secure environment

- Connect with loved ones

- Have an opportunity to talk or journal their experience if and when they choose

- Receive resources and information about how to seek counseling, particularly if their distress from the incident is interfering with their daily lives

- Protect their privacy (e.g. avoid media overexposure including watching and listening to news and participating in media interviews)

- Take time to adjust back into family and work

Family and friends can support survivors by listening, being patient, and focusing on their freedom instead of engaging in negative talk about the captors.

It is important to realize that families and friends of hostages are confronted with numerous issues in coping with fears and uncertainties as well and may also need support in dealing with their own emotional reactions.

Recovery and the future

Released hostages need time to recover from the physical, mental, and emotional difficulties they faced. However, it is important to keep in mind that human beings are highly resilient and can persevere in spite of tragedy. Research shows that positive growth and resilience can occur following trauma.

Hostage survivors may feel lost or have difficulty managing intense reactions and may need help adjusting to their old life following release. If there are chronic indications of stress, continued feelings of numbness, disturbed sleep, as well as other signs, the hostage survivor might want to consider seeking help from a licensed mental health professional, such as a psychologist, who can help develop an appropriate strategy for moving forward.

To find a psychologist in your area, visit APA’s Psychologist Locator .

Thanks to psychologists Raymond Hanbury, PhD, ABPP, and David Romano, PhD, for their assistance with this article.

Bonanno, G., Papa, A., & O’Neill, K. (2001) Loss and Human Resilience. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 10, 193–206.

Speckhard, A., Tabrina, N., Krasnov, V., & Mufel, N. (2005) “Stockholm Effects and Psychological Responses to Captivity in Hostages Held by Suicidal Terrorists” in S. Wessely & V. Krasnov eds. Psychological Responses to the new Terrorism: A NATO Russia Dialogue , IOS Press. pg. 29.

Wessely, S. (2005) Victimhood and Resilience. New England Journal of Medicine, 353, 548–550.

Recommended Reading

Related Reading

- Living well on dialysis

- Recovering from wildfires

You may also like

Advertisement

A Systematic Review of Abduction Prevention Research for Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

- REVIEW ARTICLE

- Published: 14 February 2022

- Volume 34 , pages 937–961, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Christine M. Drew ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3995-6678 1 ,

- Sarah G. Hansen 2 &

- Caroline Bell 1

522 Accesses

Explore all metrics

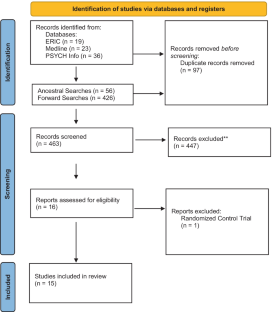

While abduction remains a rare occurrence in the United States, many parents and caregivers have concerns about children’s reactions to strangers and other safety-related behaviors. Abduction is a risk for all children, but may be of specific concern for people with disabilities due to social skill and communication deficits. Behavior analytic interventions can be used to address skill deficits that may leave children with disabilities vulnerable. Systematic searches of electronic databases, forward, and ancestral searches were conducted to find available research on interventions that address abduction-prevention skills for people with disabilities. Fifteen articles were found and summarized. Current interventions assessed in this research included: behavior skills training, in-situ training, video modeling, and social stories, which were used both alone and in combination. Lures were presented mostly by unknown strangers with some studies including responding to uniformed police officers and known individuals. Generalization and maintenance data were included in the majority of studies, and many studies assessed social validity. Research methods were assessed using the What Works Clearinghouse standards and data were assessed using standards for visual analysis. Limitations of the current research are discussed, and future research recommendations are presented.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Safe-Word Intervention for Abduction Prevention in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders

Behavioral skills training to improve the abduction-prevention skills of children with autism.

Teaching Safety Skills to Individuals with Developmental Disabilities

Availability of data and material.

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Abadir, C. M., DeBar, R. M., Vladescu, J. C., Reeve, S. A., & Kupferman, D. M. (2021). Effects of video modeling on abduction-prevention skills by individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis . https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.822

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Anderson, C., Law, J. K., Daniels, A., Rice, C., Mandell, D. S., Hagopian, L., & Law, P. A. (2012). Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 130 (5), 870–877. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0762

Annaz, D., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Johnson, M. H., & Thomas, M. S. (2009). A cross-syndrome study of the development of holistic face recognition in children with autism, Down syndrome, and Williams syndrome. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102 (4), 456–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2008.11.005

Achard, P., & Charpin, A. (2020). Stranger Danger: Parental Attitudes, Child Development and the Fear of Kidnapping.

Banda, D. R., Neisworth, J. T., & Lee, D. L. (2003). High-probability request sequences and young children: Enhancing compliance. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 25 (2), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v25n02_02

Article Google Scholar

Beck, K. V., & Miltenberger, R. G. (2009). Evaluation of a commercially available program and in situ training by parents to teach abduction-prevention skills to children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42 (4), 761–772. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2009.42-761

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Berg, K. L., Shiu, C. S., Feinstein, R. T., Acharya, K., MeDrano, J., & Msall, M. E. (2019). Children with developmental disabilities experience higher levels of adversity. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 89 , 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.03.011

Bergstrom, R., Najdowski, A. C., & Tarbox, J. (2014). A systematic replication of teaching children with autism to respond appropriately to lures from strangers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47 (4), 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.175

British Broadcasting Company. (2018). Larry Nassar Case: USA Gymnastics doctor ‘abused 265 girls’. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-42894833

Bruck, M., London, K., Landa, R., & Goodman, J. (2007). Autobiographical memory and suggestibility in children with autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 19 (1), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070058

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2017). Crime against persons with disabilities, 2009–2015 – statistical tables. Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/capd0915st_sum.pdf . Accessed 21 May 2021.

Collie, C. J., & Shalev Greene, K. (2016). The effectiveness of victim resistance strategies against stranger child abduction: An analysis of attempted and completed cases. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 13 (3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1457

Dogoe, M., & Banda, D. R. (2009). Review of recent research using constant time delay to teach chained tasks to persons with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44 (2), 177–186.

Google Scholar

Doyle, T. F., Bellugi, U., Korenberg, J. R., & Graham, J. (2004). “Everybody in the world is my friend” hypersociability in young children with Williams syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 124 (3), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.20416

Finkelhor, D. (2002). Nonfamily abducted children: National estimates and characteristics . US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Fisher, M. H., Burke, M. M., & Griffin, M. M. (2013). Teaching young adults with disabilities to respond appropriately to lures from strangers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46 (2), 528–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.32

Gast, D. L., Collins, B. C., Wolery, M., & Jones, R. (1993). Teaching preschool children with disabilities to respond to the lures of strangers. Exceptional Children, 59 (4), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299305900403

Giannakakos, A. R., Vladescu, J. C., Kisamore, A. N., Reeve, K. F., & Fienup, D. M. (2020). A review of the literature on safety response training. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29 (1), 64–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-019-09347-4

Godish, D., Miltenberger, R., & Sanchez, S. (2017). Evaluation of video modeling for teaching abduction prevention skills to children with autism spectrum disorder. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 1 (3), 168–175.

Gunby, K. V., Carr, J. E., & Leblanc, L. A. (2010). Teaching abduction-prevention skills to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43 (1), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2010.43-107

Gunby, K. V., & Rapp, J. T. (2014). The use of behavioral skills training and in situ feedback to protect children with autism from abduction lures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47 (4), 856–860. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.173

Johnson, B. M., Miltenberger, R. G., Egemo-Helm, K., Jostad, C. M., Flessner, C., & Gatheridge, B. (2005). Evaluation of behavioral skills training for teaching abduction-prevention skills to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38 (1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2005.26-04

Johnson, B. M., Miltenberger, R. G., Knudson, P., Egemo-Helm, K., Kelso, P., Jostad, C., & Langley, L. (2006). A preliminary evaluation of two behavioral skills training procedures for teaching abduction-prevention skills to schoolchildren. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39 (1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2006.167-04

Jones, L., Bellis, M. A., Wood, S., Hughes, K., McCoy, E., Eckley, L., & Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 380 (9845), 899–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60692-8

Jung, S., & Sainato, D. M. (2013). Teaching play skills to young children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 38 (1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2012.732220

Kerns, C. M., Winder-Patel, B., Iosif, A. M., Nordahl, C. W., Heath, B., Solomon, M., & Amaral, D. G. (2021). Clinically significant anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder and varied intellectual functioning. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1703712

Khemka, I., & Hickson, L. (2017). Empowering women with intellectual and developmental disabilities to resist abuse in interpersonal relationships: Promising interventions and practices. In Religion, Disability, and Interpersonal Violence, (pp. 67–86). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56901-7_5

Kurt, O., & Kutlu, M. (2019). Effectiveness of social stories in teaching abduction-prevention skills to children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49 (9), 3807–3818.

Ledbetter-Cho, K., Lang, R., Davenport, K., Moore, M., Lee, A., O’Reilly, M., Watkins, L., & Falcomata, T. (2016). Behavioral skills training to improve the abduction-prevention skills of children with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9 (3), 266–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0128-x

Ledbetter-Cho, K., Lang, R., Lee, A., Murphy, C., Davenport, K., Kirkpatrick, M., Schollian, M., Moore, M., Billingsley, G., & O’Reilly, M. (2019). Teaching children with autism abduction-prevention skills may result in overgeneralization of the target response. Behavior Modification, 45 (3), 438–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445519865165

Ledford, J. R., & Gast, D. L. (Eds.). (2014). Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Levesque-Wolfe, M. A., Rodriguez, N. M., & Niemeier-Beck, J. J. (2021). Consideration of both discriminated and generalized responding when teaching children with autism abduction prevention skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00541-9

Linder, C., & Lacy, M. (2020). Blue Lights and Pepper Spray: Cisgender College Women’s Perceptions of Campus Safety and Implications of the “Stranger Danger” Myth. The Journal of Higher Education, 91 (3), 433–454.

Mervis, C. B., & John, A. E. (2010). Cognitive and behavioral characteristics of children with Williams syndrome: implications for intervention approaches. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 154 (2), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.30263

Miller, J. M., Kurlycheck, M., Hansen, J. A., & Wilson, K. (2008). Examining child abduction by offender type patterns. Justice Quarterly, 25 (3), 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820802241697

Miller, H. L., Pavlik, K. M., Kim, M. A., & Rogers, K. C. (2017). An exploratory study of the knowledge of personal safety skills among children with developmental disabilities and their parents. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30 (2), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12239

Miltenberger, R. G., Fogel, V. A., Beck, K. V., Koehler, S., Shayne, R., Noah, J., McFee, K., Perdomo, A., Chan, P., Simmons, D., & Godish, D. (2013). Efficacy of the stranger safety abduction-prevention program and parent-conducted in situ training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46 (4), 817–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.80

Moran, E., Warden, D., Macleod, L., Mayes, G., & Gillies, J. (1997). Stranger-danger: What do children know? Child Abuse Review: Journal of the British Association for the Study and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, 6 (1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0852(199703)6:1%3c11::AID-CAR286%3e3.0.CO;2-G

Moscowitz, L., & Duvall, S. S. (2011). “Every parent’s worst nightmare” myths of child abductions in US news. Journal of Children and Media, 5 (2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2011.558267

National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. (2019). Missing Children Statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.missingkids.org/footer/media/keyfacts#missingchildrenstatistics . Accessed 15 Mar 2021.

Pan-Skadden, J., Wilder, D. A., Sparling, J., Severtson, E., Donaldson, J., Postma, N., & Neidert, P. (2009). The use of behavioral skills training and in-situ training to teach children to solicit help when lost: A preliminary investigation. Education and Treatment of Children, 32 (3), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.0.0063

Park, E. Y. (2020). Meta-analysis on the Safety Skill Training of Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1761540

Park, J., Bouck, E., & Duenas, A. (2019). The effect of video modeling and video prompting interventions on individuals with intellectual disability: A systematic literature review. Journal of Special Education Technology, 34 (1), 3–16.

Perry, D. M., & Carter-Long, L. (2016). The Ruderman white paper on media coverage of law enforcement use of force and disability, a media study (2013–2015) and overview. The Ruderman Family Foundation. https://rudermanfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/MediaStudy-PoliceDisability_final-final.pdf . Accessed 9 Apr 2021.

Reimers, T. M., Wacker, D. P., Derby, K. M., & Cooper, L. J. (1995). Relation between parental attributions and the acceptability of behavioral treatments for their child’s behavior problems. Behavioral Disorders, 20 (3), 171–178.

Rodriguez, C. N., & Jackson, M. L. (2020). A safe-word intervention for abduction prevention in children with autism spectrum disorders. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13 , 872–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00418-x

Sanchez, S., & Miltenberger, R. G. (2015). Evaluating the effectiveness of an abduction prevention program for young adults with intellectual disabilities. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 37 (3), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2015.1071178

Santoro, A. F., Shear, S. M., & Haber, A. (2018). Childhood adversity, health and quality of life in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62 (10), 854–863. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12540

Sedlak, A. J., Finkelhor, D., & Brick, J. M. (2017). National estimates of missing children: Updated findings from a survey of parents and other primary caretakers . Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. NCJ, 250089.

Sigafoos, J., O’Reilly, M., Cannella, H., Edrisinha, C., de la Cruz, B., Upadhyaya, M., ... & Young, D. (2007). Evaluation of a video prompting and fading procedure for teaching dish washing skills to adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education , 16 (2), 93–109

Sinclair, J., Hansen, S. G., Machalicek, W., Knowles, C., Hirano, K. A., Dolata, J. K., & Murray, C. (2018). A 16-year review of participant diversity in intervention research across a selection of 12 special education journals. Exceptional Children, 84 (3), 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402918756989

Spivey, C. E., & Mechling, L. C. (2016). Video modeling to teach social safety skills to young adults with intellectual disability. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51 (1), 79–92.

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10 (2), 349–367.

Summers, J., Tarbox, J., Findel-Pyles, R. S., Wilke, A. E., Bergstrom, R., & Williams, W. L. (2011). Teaching two household safety skills to children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5 (1), 629–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.07.008

Tekin-Iftar, E., Olcay, S., Sirin, N., Bilmez, H., Degirmenci, H. D., & Collins, B. C. (2021). Systematic review of safety skill interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Special Education, 54 (4), 239–250.

Ten Eycke, K. D., & Müller, U. (2015). Brief report: New evidence for a social-specific imagination deficit in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45 (1), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2206-7

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. What Works Clearinghouse.

Vasa, R. A., Keefer, A., McDonald, R. G., Hunsche, M. C., & Kerns, C. M. (2020). A scoping review of anxiety in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 13 (12), 2038–2057. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2395

White, C., Shanley, D. C., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Walsh, K., Hawkins, R., & Lines, K. (2018). “Tell, tell, tell again”: The prevalence and correlates of young children’s response to and disclosure of an in-vivo lure from a stranger. Child Abuse & Neglect, 82 , 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.06.001

Wilson, B. J., Martins, N., & Marske, A. L. (2005). Children’s and parents’ fright reactions to kidnapping stories in the news. Communication Monographs, 72 (1), 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/0363775052000342526

Wichnick-Gillis, A. M., Vener, S. M., & Poulson, C. L. (2016). The effect of a script-fading procedure on social interactions among young children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 26 , 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2016.03.004

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Special Education, Rehabilitation, and Counseling, Auburn University, Haley Center 2084, Auburn, AL, 36849, USA

Christine M. Drew & Caroline Bell

Department of Learning Sciences, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Sarah G. Hansen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christine M. Drew .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval, consent to participate, consent to publication, conflicts of interest, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Drew, C.M., Hansen, S.G. & Bell, C. A Systematic Review of Abduction Prevention Research for Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J Dev Phys Disabil 34 , 937–961 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-022-09834-z

Download citation

Accepted : 10 January 2022

Published : 14 February 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-022-09834-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Abduction prevention

- Intellectual and developmental disabilities

- Literature review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

NCJRS Virtual Library

Kidnapping: a brief psychological overview (from understanding and responding to the terrorism phenomenon: a multi-dimensional perspective, p 231-241, 2007, ozgur nikbay and suleyman hancerli, eds. -- see ncj-225118), additional details.

Nieuwe Hemweg 6B , 1013 BG Amsterdam , Netherlands

No download available

Related topics.

- Search UNH.edu

- Search Crimes against Children Research Center

Commonly Searched Items:

- Research Topics

- Meet the Co-Chairs

- Call for Abstracts and Abstract Submisson

- Exhibitor, Sponsor & Advertisement Opportunities

- Venue and Lodging

- Deadlines and Fees

- Researchers and Staff

- History and Funding

- Victim Services

- News and Media

- Training and Events

- Story Archive

- Publications

- Bullying/Peer victimization

- Bystander Behavior

- Child Advocacy Centers

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children

- Exposure to Domestic Violence

- Firearm Violence

- General Child Victimization

- Hate and Bias Victimization

- Impacts of Child Victimization

- Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire JVQ

- Kidnapping and Missing Children

- Physical Abuse

- Polyvictimization ACES (adverse childhood experiences)

- Self-Directed Violence

- Sexual Abuse

- Sexual and Gender Minority Youth

- Sibling Aggression and Abuse

- Technology/Internet Victimization

- Trends in Child Victimization

- Vicarious Trauma

Crimes against Children Research Center

- Bullying/Peer Victimization

- Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children (Sex Trafficking)

- Administering the JVQ-R2

- Available Versions of the JVQ-R2

- Ethical and Legal Issues

- Interpreting JVQ-R2 Scores

- JVQ Translations

- Scoring the JVQ-R2

- Why Ask About Youth Victimization?

- Trends In Child Victimization

- Advisory Board

- Sustainability

- Embrace New Hampshire

- University News

- The Future of UNH

- Campus Locations

- Calendars & Events

- Directories

- Facts & Figures

- Academic Advising

- Colleges & Schools

- Degrees & Programs

- Undeclared Students

- Course Search

- Academic Calendar

- Study Abroad

- Career Services

- How to Apply

- Visit Campus

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Net Price Calculator

- Graduate Admissions

- UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law

- Housing & Residential Life

- Clubs & Organizations

- New Student Programs

- Student Support

- Fitness & Recreation

- Student Union

- Health & Wellness

- Student Life Leadership

- Sport Clubs

- UNH Wildcats

- Intramural Sports

- Campus Recreation

- Centers & Institutes

- Undergraduate Research

- Research Office

- Graduate Research

- FindScholars@UNH

- Business Partnerships with UNH

- Professional Development & Continuing Education

- Research and Technology at UNH

- Request Information

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

Kidnapping Research Paper

View sample crime research paper on kidnapping. Browse criminal justice research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Kidnapping is a widely known felony that may be described as the seizing and carrying away of another person against his or her will. The precise statutory definitions are much more elaborate than the foregoing, and occur in a variety of different forms. Most statutes also prohibit the unlawful restraint of another person. Kidnapping is primarily regulated by state law, though certain federal laws may apply depending on the nature of the offense. In practice, a kidnapping may occur either by the use of force or by deception or enticement. Despite the connotation of the word ‘‘kidnapping,’’ these statutes criminalize the taking of adults as well as children. Thus, a hostage-style holding or taking captive of an adult is prosecutable under kidnapping laws. Many kidnap attempts include requests for ransom money, though this is not necessarily an element of the offense. There are related laws for hostage-taking and ransom demands, and the elements of kidnapping may often overlap with these and other crimes.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, origins of the offense in english law.

Kidnapping laws have been found as far back as three thousand years, where it was written in ancient Jewish law that ‘‘Anyone who kidnaps another and either sells him or still has him when he is caught must be put to death’’ (Exod. 21:16). The earliest ancient English kidnapping law was called ‘‘plagium,’’ and was also punishable by death. The term ‘‘kidnapping’’ is said to have emerged in English law in the late 1600s, referring to the abduction of persons who were then transported to the North American colonies for slavery. William Blackstone, writing in the late 1700s, described the law of kidnapping as the ‘‘forcible abduction or stealing away of a man, woman, or child, from their own country, and sending them into another’’ (p. 955). ‘‘This is unquestionably a very heinous crime, as it robs the king of his subjects, banishes a man from his country, and may in its consequences be productive of the most cruel and disagreeable hardships; and therefore the common law of England has punished it with fine, imprisonment, and pillory’’ (pp. 955–956).

The focus of these early laws, at least in form if not practice, seems to be on the wrongfulness of transporting someone against their will to a different country or place. Given limits of transportation centuries ago, being carried off to a different country was likely to be permanent. Today, however, the law recognizes the additional evil of detaining someone against their will even without transporting him or her to a different region.

The old English common law also contained very similar laws against ‘‘abduction,’’ such as ‘‘the forcible abduction and marriage’’ of a woman (Blackstone, p. 951). The stealing of children from a father was also criminal, as this was seen as not just the stealing of the father’s children, but also his ‘‘heir’’ (pp. 696–697). By contrast, the rationale behind the modern American laws is based on liberty, even for children, as opposed to a loss on the part of their parents or anyone else. The terms ‘‘abduction’’ and ‘‘kidnapping’’ are often used interchangeably. Where they may have had different historical connotations, their use in modern parlance has gradually become synonymous.

Impact of The Lindbergh Kidnapping

The details of the history of the American law of kidnapping are sparse at best, at least until the notorious kidnapping and murder of the oneyear-old son of the famous aviator Charles A. Lindbergh. The capture and trial of the kidnapper, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, sparked great national attention in 1932. Hauptmann was not even tried for kidnapping, which would only have been a high misdemeanor under New Jersey law at the time. With inadequate evidence to prove premeditated murder, the prosecution eventually convicted Hauptmann under the felony murder doctrine for a death resulting during the course of a burglary. Stealing a child was not covered under the burglary laws, so Hauptmann was convicted (and eventually executed) for a death that resulted during the theft of the baby’s clothes ( State v. Hauptmann, 115 N.J.L. 412 (1935)).

This episode caught the nation’s attention and sparked legislative action even before the trial was completed. The result was the so-called Lindbergh Law, adopted by Congress (18 U.S.C. §§ 1201–1202). The Lindbergh Law makes kidnapping a federal crime when the abducted individual is taken across state lines. Though not originally a capital offense, the law was later amended to give juries the discretion to recommend the death penalty in particularly heinous cases. The Supreme Court later declared the death penalty unconstitutional as it applied to the Lindbergh Law ( U.S. v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968)).

Elements of Kidnapping and Related Offenses