How to Write a Critical Response Essay: Step-by-Step Guide

Graduating without sharpening your critical thinking skills can be detrimental to your future career goals. To spare you the trouble, college teachers assign critical response tasks to prepare learners for making rational decisions.

Critical response papers also help professors assess the knowledge of each student on a relevant topic. They expect learners to conduct an in-depth analysis of each source and present their opinions based on the information they managed to retrieve.

This article aims to help students who have no idea how to write critical response essays. It offers insight into academic structuring, formatting, and editing rules. Here is our step-by-step recipe for writing a critical response essay.

What Is a Critical Response Essay?

The critical response essay displays the writer’s reaction to a written work. By elaborating on the content of a book, article, or play, you should discuss the author’s style and strategy for achieving the intended purpose. Ideally, the paper requires you to conduct a rhetorical analysis, interpret the text, and synthesize findings.

Instead of sharing somebody else’s solution on the subject matter, here you present your argumentation. Unlike a descriptive essay, this paper should demonstrate your strong expository skills. Often, a custom writing service can prove helpful if you find your evaluation essay time-consuming. Offering a value judgment about a specific topic takes time to acquire.

Another thing you should consider is not just focusing on the flaws. Though this is not a comparison and contrast essay, you must also reveal the strengths and present them without exaggeration. What matters is to develop your perspective on the work and how it affects the readership through implicit and explicit writing means.

Besides assessing your ability to develop coherent argumentation, professors will also grade your paper composition skills. They want to ensure you can critically reflect on various literature pieces. Hence, it’s essential to learn to analyze your topic thoroughly. This way, you gain a deep understanding and can organize a meaningful text.

Critical Response Essay & Other Essay Types

Standard essays contain three main segments: introduction, main body, and conclusion. But any other aspect beyond this vague outline differs depending on the assigned type. And while your critical response resembles an opinion essay since it expresses your viewpoint, you must distinguish it from other kinds.

For example, let’s consider a classification essay or a process essay. The first only lists the features of a particular object or several concepts to group them into categories. The second explains how something happens in chronological order and lists the phases of a concrete process. Hence, these variants are purely objective and lack personal reflection.

A narrative essay is more descriptive, with a focal point to tell a story. Furthermore, there’s the definition essay, an expository writing that provides information about a specific term. The writer, while showcasing their personal interpretation, must avoid criticism of the matter. Professional personal statement writers can provide assistance in creating the best essay that reflects the writer’s individual opinion.

Finally, though you can find some resemblances with an argumentative paper, critical responses comprise two parts. First, you quickly make an analytical summary of the original work and then offer a critique of the author’s writing. When drafting, it’s advisable to refrain from an informal essay format.

What Is the Structure of a Critical Response Essay?

The critical essay will have a typical structure consisting of five paragraphs. It is the most effective and easiest to follow. Here’s a brief demonstration of what you should include in each segment.

Introduction

The introductory paragraph reveals your main argument related to the analysis. You should also briefly summarize the piece to acquaint the reader with the text. The purpose of the introduction is to give context and show how you interpreted the literary work.

These paragraphs discuss the main themes in the book or article. In them, ensure you provide comments on the context, style, and layout. Moreover, include as many quotations from the first-hand text or other sources to support your interpretation.

However, finding memorable quotes and evidence in the original book can be challenging. If you have difficulties drafting a body paragraph, write your essay online with the help of a custom writing platform. These experts will help you show how you reached your conclusions.

This paragraph restates all your earlier points and how they make sense. Hence, try to bind all your comments together in an easily digestible way for your readers. The ultimate purpose is to help the audience understand your logic and unify the essay’s central idea with your interpretations.

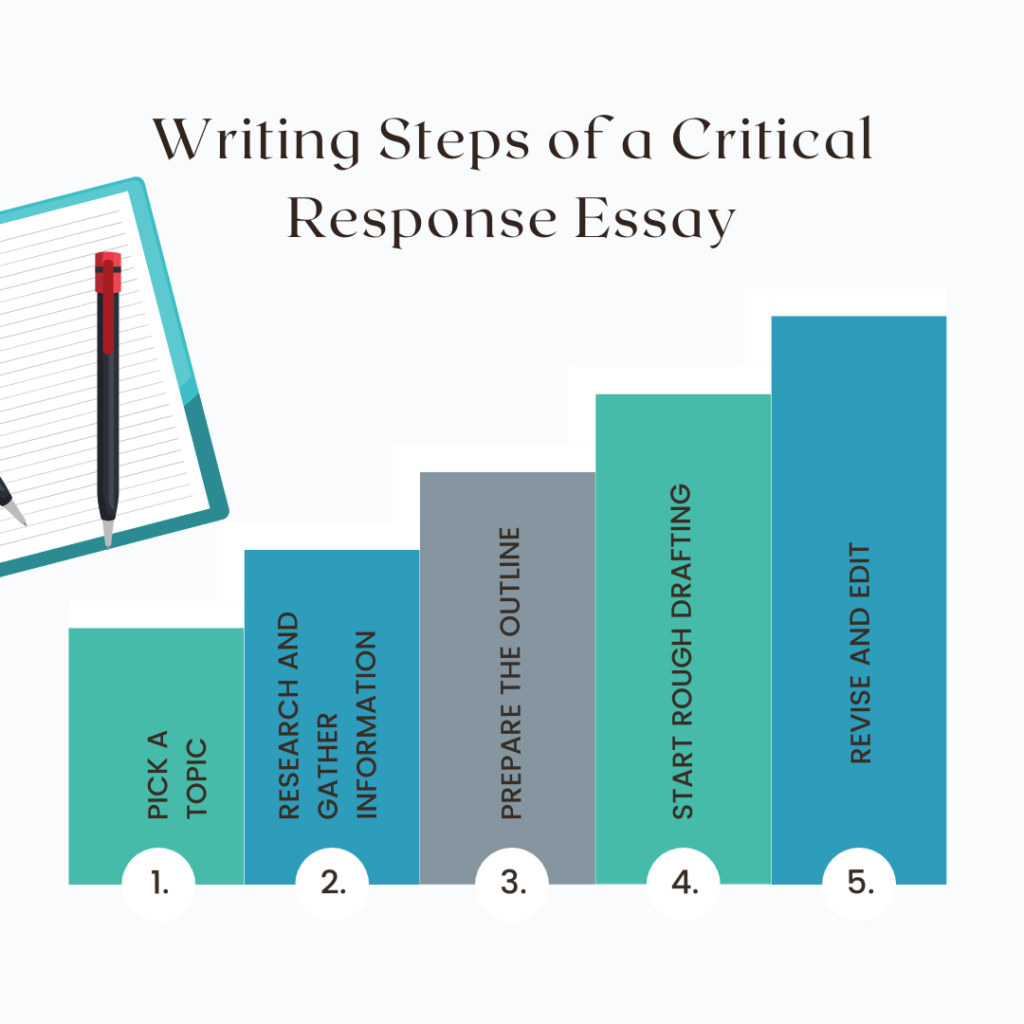

Writing Steps of a Critical Response Essay

If you wonder how to write a critical response, remember that it takes time and proper planning. You will have to address multiple data, draft ideas, and rewrite your essay fast and efficiently. Follow the methods below to organize better and get a high grade without putting too much pressure on your shoulders.

1. Pick a Topic

Professors usually choose the topic and help you grasp the focus of the research. Yet, in some cases, you might be able to select a theme you like. When deciding, ensure the book can provide several arguments, concepts, or phenomena to review. You should also consider if there’s enough available data for analysis.

2. Research and Gather Information

This assignment means you cannot base your argumentation on personal beliefs and preferences. Instead, you must be flexible and accept different opinions from acknowledged scholarly sources. Moreover, ensure you have a reliable basis for your comments.

In short, avoid questionable resources and be accurate when referencing. Finding a single article claiming the concept or idea is correct and undisputable isn’t enough. You must read and consult various sources and conduct a meticulous examination.

3. Prepare the Outline

Define your claim or thesis statement and think of a “catch” sentence that will attract the reader’s attention. You must also consider titling an essay and giving background data and facts. At this stage, it’s also recommendable to establish the number of body segments. This step will help you get a more precise writing plan you will later reinforce with examples and evidence.

4. Start Rough Drafting

When writing your first draft, consider dedicating each section to a distinct argument or supporting evidence that proves your point. Cite and give credit as appropriate and ensure your text flows seamlessly and logically. Also, anticipate objections from opponents by including statements grounding your criticism.

5. Revise and Edit

Typically, your rough draft will require polishing. The best approach is to sleep on it to reevaluate its quality in detail. Check the relevance of your thesis statement and argumentation and ensure your work is free of spelling and grammatical mistakes. Also, your sentences should be concise and straight to the point, without irrelevant facts or fillers.

The Dos and Don’ts in Critical Response Essay Writing

Check your work against the following dos and don’ts for a perfect written piece.

- Pick an intriguing title.

- Cite each source, including quotations and theoretical information.

- Connect sentences by using transition words for an essay like “First,” “Second,” “Moreover,” or “Last” for a good flow.

- Start writing in advance because last-minute works suffer from poor argumentation and grammar.

- Each paragraph must contain an analysis of a different aspect.

- Use active verbs and dynamic nouns.

- Ask a friend or classmate to proofread your work and give constructive comments.

- Check the plagiarism level to ensure it’s free of copied content.

- Don’t exceed the specified word limit.

- Follow professional formatting guidelines.

- Your summary must be short and not introduce new information.

- Avoid clichés and overusing idioms.

- Add the cited bibliography at the end.

Related posts:

- Persuasive Essay: a Comprehensive Guide & Help Source

- How to Write a News Story

- How to Write an Autobiography Essay: Guide for College Students

- A Foolproof Guide to Creating a Causal Analysis Essay

Improve your writing with our guides

How to Write a Scholarship Essay

Definition Essay: The Complete Guide with Essay Topics and Examples

Critical Essay: The Complete Guide. Essay Topics, Examples and Outlines

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing the Critical Response Essay (CRE)

The Critical Response Essay is a multi-paragraph, multi-page essay that requires you to take one of your Critical Response Paragraphs and revise it to create a more complex and stronger argument. You should choose your best CRP or the one that most interests you. Focus on making it not only a longer argument, but also a better argument, using what you’ve learned since writing the original piece to improve the argument and the writing itself (argument form, paragraph form, and grammar). Also use what you’ve learned from my feedback and from our discussions in class and individual conferences. You must include confutation.

ARGUMENT FORM

CREs require that you use classical argument form. The parts of this kind of argument are as follow:

Key Takeaways

- Introduction Paragraph , ending with claim

- [ Confutation as first argument paragraph ?]

- Argument Paragraphs (two or three): Begin with a subclaim , then support it by providing textual evidence and analysis of evidence [including confutation within?]

- [ Confutation as final argument paragraph ?]

- Conclusion [confutation as conclusion?]

- Works Cited

Your title may not be simply the title of the story or the assignment. It must be a title that is specific to your argument.

INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPH with CLAIM

- Introduce the story and the author about which you are writing. If you’re writing about a film, identify the director.

- Call attention to the features of the story on which you will base your argument. This is the ONLY part of the essay in which you may summarize parts of the story.

- END the introduction with your CLAIM.

- If you have no claim, you have no argument, and therefore you may earn a disappointing grade.

- Likewise, if your claim does not appear in the introduction, your reader has no way of knowing what your subclaims and evidence are attempting to prove.

- It’s not like a joke where you save the punchline until last.

- It’s not mystery-writing, where you don’t identify the murderer until the end.

- It’s an argument. So for your reader to understand what is the point of all the evidence and analysis you’re working so hard to create, you must tell her, in the introduction, what you’re trying to argue and prove.

Writing an Arguable Claim

- Think in terms of theme .

- Theme cannot be expressed with just a word or even a short phrase, like sibling rivalry or fear of marriage. Those are interesting topics, but they are not yet themes.

- To turn a topic into a theme, you must be able to say what the story shows us about the topic , that relates to real life beyond the story.

“Beauty and the Beast” illustrates sibling rivalry.

This is an insufficient claim about theme because it doesn’t give me even a hint of what you think the story says about sibling rivalry. Unless you plan to tell me that in the next sentence, there’s a problem with your claim. By the way, a claim can be more than one sentence.

Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s “Beauty and the Beast” illustrates how sibling rivalry can be caused by unnecessary competition for mates, particularly in the case of sisters.

Now that’s an arguable claim because it includes author, title, a topic, and what the story says about the topic and how it relates to real life.

You can make this claim even stronger (and give yourself greater confidence that your argument will be persuasive) by including the main textual evidence you will cite.

Or you could revise this idea to discuss how cultural expectations play a role in this kind of rivalry and unhealthy competition. See the CRP Example for something like that.

If it helps, you can think of these components as part of a formula.

Let X be the story and some particular feature of it.

Let Y be the theme you are arguing.

Instead of an equal sign, we insert a verb that expresses the relationship between X and Y:

(=) illustrates, shows, portrays, dramatizes, suggests (etc.)

In this example:

Let X be the elder sisters’ resentment toward Beauty.

Let Y be how sibling rivalry can be caused by competition for mates.

Notice in the example below how this process creates an arguable claim.

(X) The elder sisters’ resentment toward Beauty in “Beauty and the Beast”

(Y) how sibling rivalry can be caused by competition for mates.

ARGUMENT PARAGRAPHS

- Support the claim with argument paragraphs.

- How many you need is up to you, but generally at least two, in some cases three or four.

- Begin EVERY argument paragraph with a TOPIC SENTENCE

- The topic sentence is like a mini-claim, the paragraph’s claim

- Tells me what you’ll argue in this paragraph

- And tells or shows how this point supports the main claim.

- Support the topic sentence with textual evidence and analysis

- Quotations and your analysis of them.

- See the Quotation Sandwich document for guidance.

- Vary the verbs you use to incorporate quotations into your sentences. DO NOT use the words “says,” “states,” or “writes” (or any forms of these verbs). See the document titled “Effective Verbs for Introducing Quotations in Canvas for many possible verbs that you may use.

- Use transitional terms—also called “signposts”—to show the relationships from one point to the next and from one paragraph to the next. The internet is full of lists of transitional terms. Here’s one good source: Transition Words.

CONFUTATION

Confutation makes an argument stronger by dealing with opposing points and evidence.

- Confutation includes the following parts:

- Presenting opposition fairly (opposing claims or ideas)

Remember that the opposition must not be a “straw man.” That is, you must engage with something that a careful reader would actually argue, not a simplistic, obviously erroneous reading.

Some readers might argue that the sisters are not abusive toward Beauty.

This example is a straw man statement. No one would seriously argue this point because the sisters actually plot to get Beauty killed, and what could be more abusive than that?

- Refuting the opposition: showing how it is incorrect or at least as correct as your reading.

- Directly after the introduction

- o Directly before the conclusion

- o As part of the conclusion

- o Within paragraphs, to deal with possible alternative interpretations of your textual evidence.

Consider a confutation involving the fairy who appears at the end of “Beauty and the Beast” and what she does to Beauty’s sisters. That is, she punishes the two sisters for their bad behavior. Some readers see this as fair because those mean girls get what’s coming to them. But others see it as a missed opportunity to promote sisterhood among all three of the girls. Here are examples of how to write these points as a complete confutation.

State the opposition, as fairly as possible: When the fairy punishes the two sisters for their bad behavior, some readers see this extreme punishment as fair because those mean girls finally get what is coming to them.

Refute the opposition: But by imposing this punishment, the fairy misses a chance to promote sisterhood among all three of the girls. But if she has such powerful magic, that she can turn young women to stone, shouldn’t she be able to teach them to love each other instead?

This refutation includes a rhetorical question; it is not meant for you to answer, but to leave the reader thinking about your ideas. You are not required to pose your refutation as a question; this is just one way to write your refutation.

What do you do with a conclusion? Do not just restate your claim, even if you change some of the wording. That’s not worth your reader’s time. So what is worth your reader’s time?

- A kind of wrap-up: What’s the point of this argument? What has been learned here and why does it matter? What do you want you and your reader to have learned or created together?

- And why is this important? Does it apply to real life now? How?

- Certainly the spirit of your claim will be here. But not just your claim reworded.

- o Because you’ve just been feeding it and exercising it,

- o So now it’s bigger and more interesting.

- o So you should be able to talk it about it with greater complexity and authority. Don’t go crazy and add new ideas—remember you’re wrapping things up.

- Confutation as Conclusion: You may be able to write a conclusion that includes confutation. Why might this be a useful strategy? Why might it be problematic?

Understanding the difference between claim and conclusion

- the conclusion is similar to the claim

- and yet more detailed and complete in meaning.

- Notice the relationship between the CLAIM and the Conclusion in this example:

The story of “The Frog King, or Iron Henry” illustrates and even promotes the importance of consent in relationships.

In this way, the story highlights the importance of understanding and respecting the value of consent. This tale teaches readers to stand up for themselves and refuse to give in to situations that will clearly cause discomfort or danger.

Keep this guidance and these examples handy as you draft your essay, and remember that I’m happy to answer questions and review drafts within the time constraints announced in class.

Introduction to Literature Copyright © by Judy Young is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Critical Response Essay

Students have to write different types of essays all the time. However, they face many problems when it comes to writing a critical response essay. Why is it so hard to manage? What are the main components of it? We will answer all these questions in our complete guide to help you learn how you can write this type of essays quickly and easily.

What Is a Critical Response Essay?

First things first – let’s find out what a critical response essay is and what components it includes.

It is an assignment that is based on your analytical skills. It implies the understanding of the primary source, such as literary work, movie or painting (its problematic, content, and significance), and the ability to perform critical thinking and reflect your opinion on the given subject.

The aim of critical response essay is to get familiarised with the subject, form your opinion (the agreement or disagreement with the author), reveal the problematic of the piece and support your claims with evidence from the primary source.

For example, your task might be to analyze the social structure in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

How Is It Different From Other Essay Types?

Every essay you write has a very similar structure that consists of an introduction, the main body, and the conclusion. While this type is not an exception and is quite similar to an analytical essay , it still has differences. One of those is the fact that it contains two parts. The first part includes a quick summary of the analyzed work. The second part is a critique – a response to the author’s opinion, facts, examples, etc.

What Should You Pay Attention To?

Before we dive into the guide and the steps of crafting your critical essay, let’s take a look at some of the most common pitfalls that often occur during the writing process of a piece like this.

Not knowing what you are writing about.

This makes no sense, right? So, be sure to read the piece that your topic is based on and make sure you understand what it is about.

Not understanding what your task is.

Be attentive to the task and make sure you understand what is required from you. You would be surprised if you knew how many essays are written without even touching the main question or problematic.

Being in a hurry.

A lot of students start working on their essays at the very last moment and do it in haste. You can avoid a lot of mistakes if you are attentive, focused, and organized. If you have too little time to write a strong response essay yourself, you can always get the assistance of a professional writing service. This will help you to be on time with your assignment without sacrificing its quality.

And now let’s begin your journey of writing an essay.

Step 1. Examine the Primary Source

Before starting actually writing your critical essay, you need to get acquainted with the subject of your analysis. It might be an article, a book or any other type of text. Sometimes, this task is given for pieces of art, such as a painting or a movie.

So, the first step would be to gain as much information about the subject as possible. You might also search for some reviews or research papers on the subject. Be sure to examine the primary source thoroughly and read the complete text if it is a piece of writing.

Advice: make notes while you are working with your primary source. Highlight the main points that will build a basis for your analysis and which you can use to form your opinion on. Notes will also help you to structure your essay.

- Did you read the whole text or examined your primary source thoroughly?

- Did you find information on the topic of your assignment?

- Did you write down the key points that you are going to use for your essay?

Step 2. Analyze the Source and Your Notes

After you finished with your primary source, try to analyze and summarize all of your findings. Identify the problematic of the piece and find the appropriate notes that you have made to structure your future essay.

Formulate your opinion – are you agree or disagree with the author? Can you support your statements with evidence?

- Did you examine all the notes you have?

- Did you form your opinion on the subject?

- Did you find the arguments to support your main point?

- Did you succeed to define the strengths and weaknesses of the work?

Step 3. Write Your Essay

After you have all of the needed materials next to you, you can start working on the text of your essay.

- First of all, write a critical response essay rough draft.

- Reread your draft and make your edits.

- Proofread and edit your final version.

- Check for plagiarism, grammatical and punctuation errors.

- Write a Works Cited page or bibliography page (if required).

Now, we will look at each part of your essay in detail. Keep in mind that you have to follow the guidelines provided by your teacher or professor. Some critical response essay examples will come in handy at this step.

How to Write a Critical Response Introduction

Your introduction is the part where you have to provide your thesis statement. Once you have your opinion and your thoughts organized, it’s pretty easy to make them transform into a statement that all your essay will be built on. Express your agreement or disagreement with the author.

For example, your thesis statement might be:

“Romeo and Juliet” by Shakespeare is a masterpiece that raises the problem of social inequality and classes differentiation which aggravates the drama culmination.

Advice: make sure you have evidence to support your thesis statement later in the text. Make your introduction in the form of a brief summary of the text and your statement. You need to introduce your reader to the topic and express your opinion on it.

- Did you embed your thesis statement?

- Is your thesis statement complete and suitable for the topic?

- Can you support your thesis statement with evidence?

- Did you summarize the analyzed subject?

- Did you start your introduction with a catchy sentence – a powerful statement, fact, quote or intriguing content?

- Did you include a transition sentence at the end of your introduction?

How to Write Critical Response Paragraphs

Explain each of your main points in separate body paragraphs. Structure your text so that the most strong statement with the following supporting evidence is placed first. Afterward, explain your other points and provide examples and evidence from the original text.

Remember that each of your statements should support your main idea – your thesis statement. Provide a claim at the beginning of the paragraph and then develop your idea in the following text. Support each of your claims with at least one quote from the primary source.

For example:

To distinguish the division between classes and express the contribution of each social class Shakespeare used different literary methods. For example, when a person from a lower class speaks, Shakespeare uses prose:

NURSE I saw the wound, I saw it with mine eyes (God save the mark!) here on his manly breast— A piteous corse, a bloody piteous corse, Pale, pale as ashes, all bedaubed in blood, All in gore blood. I swoonèd at the sight. (3.2.58-62)

At the same time upper-class characters speak in rhymed verse:

MONTAGUE But I can give thee more, For I will raise her statue in pure gold, That while Verona by that name is known, There shall no figure at such rate be set As that of true and faithful Juliet. (5.3.309-313)

- Did you support your thesis statement with claims?

- Do your claims appeal to critical response questions?

- Did you provide evidence for each claim?

How to Write Critical Response Conclusion

The best way to conclude your essay is to restate your thesis statement in different phrasing. Summarize all of your findings and repeat your opinion on the subject. A one- or two-paragraph conclusion is usually enough if not requested more.

We’ve also prepared some critical response essay topics for you:

- Explain the changes of the character throughout the novel: Frodo from Lord of the Rings /Dorian Gray from The Picture of Dorian Gray .

- Examine a setting and the atmosphere in the novel Gone with the Wind/Jane Eyre .

- Investigate the cultural or historical background in Romeo and Juliet/Macbeth .

- Describe the impact of the supporting character: Horatio in Hamlet /Renfield in Dracula .

- Describe the genre of the work and its influence on the mood of the piece: To Build a Fire/ For Whom the Bell Tolls.

This was our step-by-step guide to writing your perfect critical response essay. We hope our tips will be useful to you!

Related posts

1.3 Glance at Critical Response: Rhetoric and Critical Thinking

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use words, images, and specific rhetorical terminology to understand, discuss, and analyze a variety of texts.

- Determine how genre conventions are shaped by audience, purpose, language, culture, and expectation.

- Distinguish among different types of rhetorical situations and communicate effectively within them.

Every day you find yourself in rhetorical situations and use rhetoric to communicate with and to persuade others, even though you might not realize you are doing it. For example, when you voice your opinion or respond to another’s opinion, you are thinking rhetorically. Your purpose is often to convince others that you have a valid opinion, and maybe even issue a call to action. Obviously, you use words to communicate and present your position. But you may communicate effectively through images as well.

Words and Images

Both words and images convey information, but each does so in significantly different ways. In English, words are written sequentially, from left to right. A look at a daily newspaper or web page reveals textual information further augmented by headlines, titles, subtitles, boldface, italics, white space, and images. By the time readers get to college, they have internalized predictive strategies to help them critically understand a variety of written texts and the images that accompany them. For example, you might be able to predict the words in a sentence as you are reading it. You also know the purpose of headers and other markers that guide you through the reading.

To be a critical reader, though, you need to be more than a good predictor. In addition to following the thread of communication, you need to evaluate its logic. To do that, you need to ask questions such as these as you consider the argument: Is it fair (i.e., unbiased)? Does it provide credible evidence? Does it make sense, or is it reasonably plausible? Then, based on what you have decided, you can accept or reject its conclusions. You may also consider alternative possibilities so that you can learn more. In this way, you read actively, searching for information and ideas that you understand and can use to further your own thinking, writing, and speaking. To move from understanding to critical awareness, plan to read a text more than once and in more than one way. One good strategy is to ask questions of a text rather than to accept the author’s ideas as fact. Another strategy is to take notes about your understanding of the passage. And another is to make connections between concepts in different parts of a reading. Maybe an idea on page 4 is reiterated on page 18. To be an active, engaged reader, you will need to build bridges that illustrate how concepts become part of a larger argument. Part of being a good reader is the act of building information bridges within a text and across all the related information you encounter, including your experiences.

With this goal in mind, beware of passive reading. If you ever have been reading and completed a page or paragraph and realized you have little idea of what you’ve just read, you have been reading passively or just moving your eyes across the page. Although you might be able to claim you “read” the material, you have not engaged with the text to learn from it, which is the point of reading. You haven’t built bridges that connect to other material. Remember, words help you make sense of the world, communicate in the world, and create a record to reflect on so that you can build bridges across the information you encounter.

Images, however, present a different set of problems for critical readers. Sometimes having little or no accompanying text, images require a different skill set. For example, in looking at a photograph or drawing, you find different information presented simultaneously. This presentation allows you to scan or stop anywhere in the image—at least theoretically. Because visual information is presented simultaneously, its general meaning may be apparent at a glance, while more nuanced or complicated meanings may take a long time to figure out. And even then, odds are these meanings will vary from one viewer to another.

In the well-known image shown in Figure 1.3 , do you see an old woman or a young woman? Although the image remains static, your interpretation of it may change depending on any number of factors, including your experience, culture, and education. Once you become aware of the two perspectives of this image, you can see the “other” easily. But if you are not told about the two ways to “see” it, you might defend a perspective without realizing that you are missing another one. Most visuals, however, are not optical illusions; less noticeable perspectives may require more analysis and may be more influenced by your cultural identity and the ways in which you are accustomed to interpreting. In any case, this image is a reminder to have an open mind and be willing to challenge your perspectives against your interpretations. As such, like written communication, images require analysis before they can be understood thoroughly and evaluation before they can be judged on a wider scale.

If you have experience with social media, you may be familiar with the way users respond to images or words by introducing another image: the meme . A meme is a photograph containing text that presents one viewer’s response. The term meme originates from the Greek root mim , meaning “mime” or “mimic,” and the English suffix -eme . In the 1970s, British evolutionary biologist and author Richard Dawkins (b. 1941) created the term for use as “a unit of cultural transmission,” and he understood it to be “the cultural equivalent of a gene.” Today, according to the dictionary definition, memes are “amusing or interesting items that spread widely through the Internet.” For example, maybe you have seen a meme of an upset cat or of a friend turning around to look at something else while another friend is relating something important. The text that accompanies these pictures provides some expression on the part of the originator that the audience usually finds humorous, relatable, or capable of arousing any range of emotion or thought. For example, in the photograph shown in Figure 1.4 of a critter standing at attention, the author of the text conveys anxiousness. The use of the word like has been popularized in the meme genre to mean “to give an example.”

While these playful aspects of images are important, you also should recognize how images fit into the rhetorical situation. Consider the same elements, such as context and genre, when viewing images. You may find multiple perspectives to consider. In addition, where images show up in a text or for an audience might be important. These are all aspects of understanding the situation and thinking critically. Engaged readers try to connect and build bridges to information across text and images.

As you consider your reading and viewing experiences on social media and elsewhere, note that your responses involve some basic critical thinking strategies. Some of these include summary, paraphrase, analysis, and evaluation, which are defined in the next section. The remaining parts of this chapter will focus on written communication. While this chapter touches only briefly on visual discourse, Image Analysis: What You See presents an extensive discussion on visual communication.

Relation to Academics

As with all disciplines, rhetoric has its own vocabulary. What follows are key terms, definitions, and elements of rhetoric. Become familiar with them as you discuss and write responses to the various texts and images you will encounter.

- Analysis : detailed breakdown or other explanation of some aspect or aspects of a text. Analysis helps readers understand the meaning of a text.

- Authority : credibility; background that reflects experience, knowledge, or understanding of a situation. An authoritative voice is clear, direct, factual, and specific, leaving an impression of confidence.

- Context : setting—time and place—of the rhetorical situation. The context affects the ways in which a particular social, political, or economic situation influences the process of communication. Depending on context, you may need to adapt your text to audience background and knowledge by supplying (or omitting) information, clarifying terminology, or using language that best reaches your readers.

- Culture : group of people who share common beliefs and lived experiences. Each person belongs to various cultures, such as a workplace, school, sports team fan, or community.

- Evaluation : systematic assessment and judgment based on specific and articulated criteria, with a goal to improve understanding.

- Evidence : support or proof for a fact, opinion, or statement. Evidence can be presented as statistics, examples, expert opinions, analogies, case studies, text quotations, research in the field, videos, interviews, and other sources of credible information.

- Media literacy : ability to create, understand, and evaluate various types of media; more specifically, the ability to apply critical thinking skills to them.

- Meme : image (usually) with accompanying text that calls for a response or elicits a reaction.

- Paraphrase : rewording of original text to make it clearer for readers. When they are part of your text, paraphrases require a citation of the original source.

- Rhetoric : use of effective communication in written, visual, or other forms and understanding of its impact on audiences as well as of its organization and structure.

- Rhetorical situation : instance of communication; the conditions of a communication and the agents of that communication.

- Social media : all digital tools that allow individuals or groups to create, post, share, or otherwise express themselves in a public forum. Social media platforms publish instantly and can reach a wide audience.

- Summary : condensed account of a text or other form of communication, noting its main points. Summaries are written in one’s own words and require appropriate attribution when used as part of a paper.

- Tone : an author’s projected or perceived attitude toward the subject matter and audience. Word choice, vocal inflection, pacing, and other stylistic choices may make the author sound angry, sarcastic, apologetic, resigned, uncertain, authoritative, and so on.

As you read through these terms, you likely recognize most of them and realize you are adept in some rhetorical situations. For example, when you talk with friends about your trip to the local mall, you provide details they will understand. You might refer to previous trips or tell them what is on sale or that you expect to see someone from school there. In other words, you understand the components of the rhetorical situation. However, if you tell your grandparents about the same trip, the rhetorical situation will be different, and you will approach the interaction differently. Because the audience is different, you likely will explain the event with more detail to address the fact that they don’t go to the mall often, or you will omit specific details that your grandparents will not understand or find interesting. For instance, instead of telling them about the video game store, you might tell them about the pretzel café.

As part of your understanding of the rhetorical situation, you might summarize specific elements, again depending on the intended audience. You might speak briefly about the pretzel café to your friends but spend more time detailing the various toppings for your grandparents. If, by chance, you have previously stopped to have a pretzel, you might provide your analysis and evaluation of the service and the food. Once again, you are engaged in rhetoric by showing an understanding of and the ability to develop a strategy for approaching a particular rhetorical situation. The point is to recognize that rhetorical situations differ, depending, in this case, on the audience. Awareness of the rhetorical situation applies to academic writing as well. You change your presentation, tone, style, and other elements to fit the conditions of the situation.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-3-glance-at-critical-response-rhetoric-and-critical-thinking

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

IMAGES

VIDEO