Theme of Loneliness, Isolation, & Alienation in Literature with Examples

Humans are social creatures. Most of us enjoy communication and try to build relationships with others. It’s no wonder that the inability to be a part of society often leads to emotional turmoil.

World literature has numerous examples of characters who are disconnected from their loved ones or don’t fit into the social norms. Stories featuring themes of isolation and loneliness often describe a quest for happiness or explore the reasons behind these feelings.

In this article by Custom-Writing.org , we will:

- discuss isolation and loneliness in literary works;

- cite many excellent examples;

- provide relevant quotations.

🏝️ Isolation Theme in Literature

- 🏠 Theme of Loneliness

- 👽 Theme of Alienation

- Frankenstein

- The Metamorphosis

- Of Mice and Men

- ✍️ Essay Topics

🔍 References

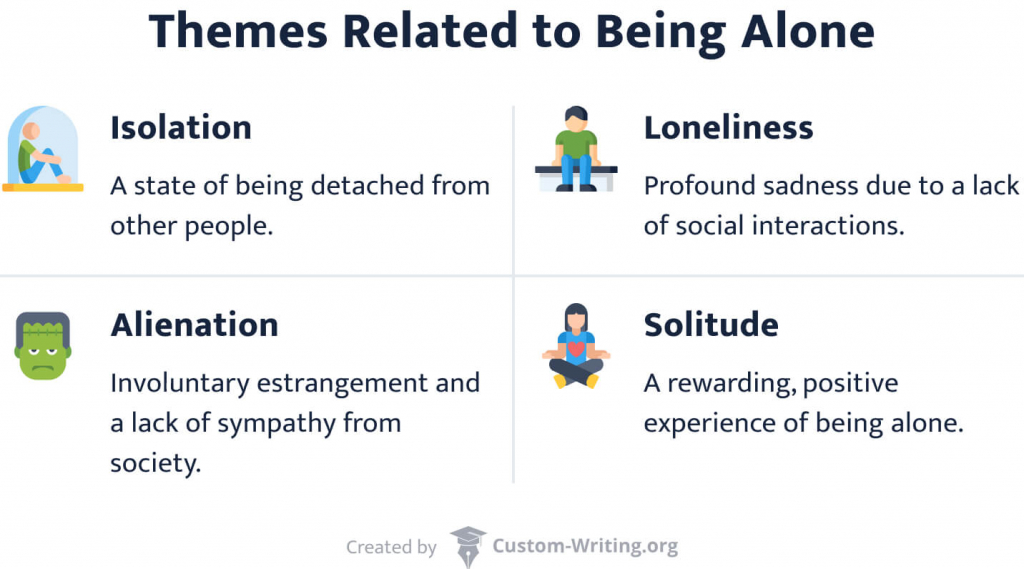

Isolation is a state of being detached from other people, either physically or emotionally. It may have positive and negative connotations:

- In a positive sense, isolation can be a powerful source of creativity and independence.

- In negative terms , it can cause mental suffering and difficulties with interpersonal relationships.

Theme of Isolation and Loneliness: Difference

As you can see, isolation can be enjoyable in certain situations. That’s how it differs from loneliness : a negative state in which a person feels uncomfortable and emotionally down because of a lack of social interactions . In other words, isolated people are not necessarily lonely.

Isolation Theme Characteristics with Examples

Now, let’s examine isolation as a literary theme. It often appears in stories of different genres and has various shades of meaning. We’ll explain the different uses of this theme and provide examples from literature.

Forced vs. Voluntary Isolation in Literature

Isolation can be voluntary or happen for external reasons beyond the person’s control. The main difference lies in the agent who imposes isolation on the person:

- If someone decides to be alone and enjoys this state of solitude, it’s voluntary isolation . The poetry of Emily Dickinson is a prominent example.

- Forced isolation often acts as punishment and leads to detrimental emotional consequences. This form of isolation doesn’t depend on the character’s will, such as in Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter .

Physical vs. Emotional Isolation in Literature

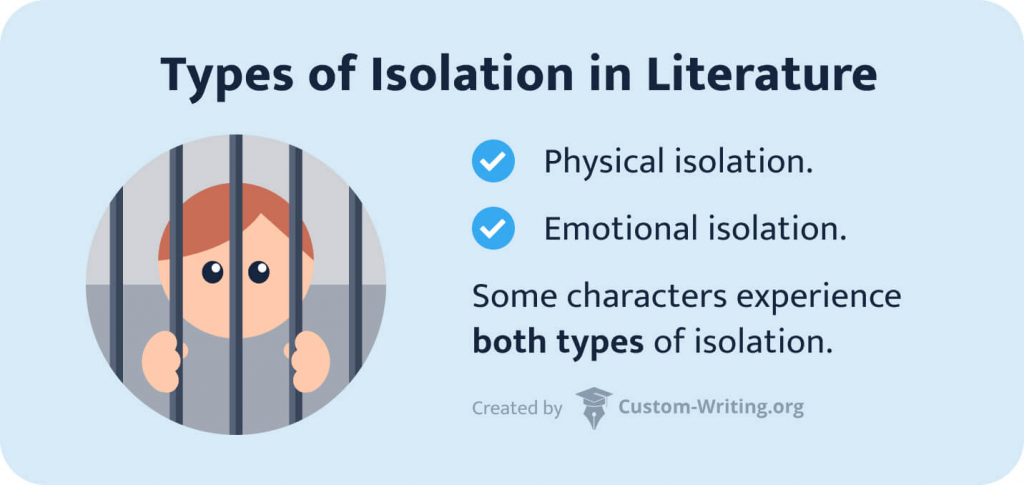

Aside from forced and voluntary, isolation can be physical or emotional:

- Isolation at the physical level makes the character unable to reach out to other people, such as Robinson Crusoe being stranded on an island.

- Emotional isolation is an inner state of separation from other people. It also involves unwillingness or inability to build quality relationships. A great example is Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye .

These two forms are often interlinked, like in A Rose for Emily . The story’s titular character is isolated from the others both physically and emotionally .

Symbols of Isolation in Literature

In literary works dedicated to emotional isolation, authors often use physical artifacts as symbols. For example, the moors in Wuthering Heights or the room in The Yellow Wallpaper are means of the characters’ physical isolation. They also symbolize a much deeper divide between the protagonists and the people around them.

🏠 Theme of Loneliness in Literature

Loneliness is often used as a theme in stories of people unable to build relationships with others. Their state of mind always comes with sadness and a low self-esteem. Naturally, it causes profound emotional suffering.

We will examine how the theme of loneliness functions in literature. But first, let’s see how it differs from its positive counterpart: solitude.

Solitude vs. Loneliness: The Difference

| is a profound sadness caused by a lack of company and meaningful relationships. | is a rewarding, positive experience of being alone. For example, some creative people seek solitude to concentrate on their art without social distractions. Importantly, they don’t feel sad about being alone. |

Loneliness Theme: History & Examples

The modern concept of loneliness is relatively new. It first emerged in the 16 th century and has undergone many transformations since then.

- The first formal mention of loneliness appeared in George Milton’s Paradise Lost in the 17 th century. There are also many references to loneliness in Shakespeare’s works.

- Later on, after the Industrial Revolution , the theme got more popular. During that time, people started moving to large cities. As a result, they were losing bonds with their families and hometowns. Illustrative examples of that period are Gothic novels and the works of Charles Dickens .

- According to The New Yorker , the 20 th century witnessed a broad spread of loneliness due to the rise of Capitalism. Philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus explored existential loneliness, influencing numerous authors. The absurdist writings of Kafka and Beckett also played an essential role in reflecting the isolation felt by people in Capitalist societies. Sylvia Plath has masterfully explored mental health struggles related to this condition in The Bell Jar (you can learn more about it in our The Bell Jar analysis .)

👽 Theme of Alienation in Literature

Another facet of being alone that is often explored in literature is alienation . Let’s see how this concept differs from those we discussed previously.

Alienation vs. Loneliness: Difference

While loneliness is more about being on your own and lacking connection, alienation means involuntary estrangement and a lack of sympathy from society. In other words, alienated people don’t fit their community, thus lacking a sense of belonging.

Isolation vs. Alienation: The Difference

| is often seen as a physical condition of separation from a social group or place. In emotional terms, it’s also similar to withdrawal from social activity. | , in turn, doesn’t necessarily involve physical separation. It’s mostly referred to as a lack of involvement and a sense of belonging while being present. It’s closely connected with the , which you can read about in our guide. |

Theme of Alienation vs. Identity in Literature

There is a prominent connection between alienation and a loss of identity. It often results from a character’s self-search in a hostile society with alien ideas and values. These characters often differ from the dominant majority, so the community treats them negatively. Such is the case with Mrs. Dalloway from Woolf’s eponymous novel.

Writers with unique, non-conforming identity are often alienated during their lifetime. Their distinct mindset sets them apart from their social circle. Naturally, it creates discomfort and relationship problems. These experiences are often reflected in their works, such as in James Joyce’s semi-autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man .

Alienation in Modernism

Alienation as a theme is mainly associated with Modernism . It’s not surprising, considering that the 20 th century witnessed fundamental changes in people’s lifestyle. Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution couldn’t help eroding the quality of human bonding and the depth of relationships.

It’s also vital to mention that the two World Wars introduced even greater changes in human relationships. People got more locked up emotionally in order to withstand the war trauma and avoid further turmoil. Consequently, the theme of alienation and comradeship found reflection in the works of Ernest Hemingway , Erich Maria Remarque , Norman Mailer, and Rebecca West, among others.

📚 Books about Loneliness and Isolation: Quotes & Examples

Loneliness and isolation themes are featured prominently in many of the world’s greatest literary works. Here we’ll analyze several well-known examples: Frankenstein, Of Mice and Men, and The Metamorphosis.

Theme of Isolation & Alienation in Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein is among the earliest depictions of loneliness in modern literature. It shows the depth of emotional suffering that alienation can impose.

Victor Frankenstein , a talented scientist, creates a monster from the human body parts. The monster becomes the loneliest creature in the world. Seeing that his master hates him and wouldn’t become his friend, he ruined everything Victor held dear. He was driven by revenge, trying to drive him into the same despair.

The novel contains many references to emotional and physical alienation. It also explores the distinction between voluntary and involuntary isolation:

- The monster is involuntarily driven into an emotionally devastating state of alienation.

- Victor imposes voluntary isolation on himself after witnessing the crimes of his creature.

To learn more about the representation of loneliness and isolation in the novel, check out our article on themes in Frankenstein .

Frankenstein Quotes about Isolation

Here are a couple of quotes from Frankenstein directly related to the theme of isolation and loneliness:

How slowly the time passes here, encompassed as I am by frost and snow…I have one want which I have never yet been able to satisfy and the absence of the object of which I now feel as a most severe evil. I have no friend. Frankenstein , Letter 2

In this quote, Walton expresses his loneliness and desire for company. He uses frost and snow as symbols to refer to his isolation. Perhaps a heart-warming relationship could melt the ice surrounding him.

I believed myself totally unfitted for the company of strangers. Frankenstein , Chapter 3

This quote is related to Victor’s inability to make friends and function as a regular member of society. He also misses his friends and relatives in Ingolstadt, which causes him further discomfort.

I, who had ever been surrounded by amiable companions, continually engaged in endeavouring to bestow mutual pleasure—I was now alone. Frankenstein , Chapter 3

In this quote, Victor shares his fear of loneliness. As a person who used to spend most of his time in social activity among people, Victor feared the solitude that awaited him in Ingolstadt.

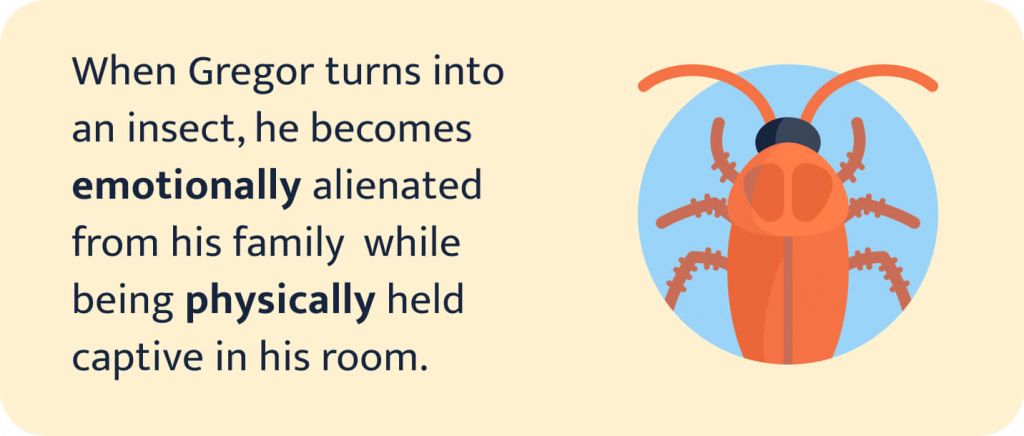

Isolation & Alienation in The Metamorphosis

The Metamorphosis is an enigmatic masterpiece by Franz Kafka, telling a story of a young man Gregor. He is alienated at work and home by his demanding, disrespectful family. He lacks deep, rewarding relationships in his life. As a result, he feels profound loneliness.

Gregor’s family isolates him both as a human and an insect, refusing to recognize his personhood. Gregor’s stay in confinement is also a reflection of his broader alienation from society, resulting from his self-perception as a parasite. To learn more about it, feel free to read our article on themes in The Metamorphosis .

The Metamorphosis: Isolation Quotes

Let’s analyze several quotes from The Metamorphosis to see how Kafka approached the theme of isolation.

The upset of doing business is much worse than the actual business in the home office, and, besides, I’ve got the torture of traveling, worrying about changing trains, eating miserable food at all hours, constantly seeing new faces, no relationships that last or get more intimate. The Metamorphosis , Part 1

In this fragment, Gregor’s lifestyle is described with a couple of strokes. It shows that he lived an empty, superficial life without meaningful relationships.

Well, leaving out the fact that the doors were locked, should he really call for help? In spite of all his miseries, he could not repress a smile at this thought. The Metamorphosis , Part 1

This quote shows how Gregor feels isolated even before anyone else can see him as an insect. He knows that being different will inevitably affect his life and his relationships with his family. So, he prefers to confine himself to voluntary isolation instead of seeking help.

He thought back on his family with deep emotion and love. His conviction that he would have to disappear was, if possible, even firmer than his sister’s. The Metamorphosis , Part 3

This final paragraph of Kafka’s story reveals the human nature of Gregor. It also shows the depth of his suffering in isolation after turning into a vermin. He reconciles with his metamorphosis and agrees to disappear from this world. Eventually, he vanishes from his family’s troubled memories.

Theme of Loneliness in Of Mice and Men

Of Mice and Men is a touching novella by John Steinbeck examining the intricacies of laborers’ relationships on a ranch. It’s a snapshot of class and race relations that delves into the depths of human loneliness. Steinbeck shows how this feeling makes people mean, reckless, and cold.

Many characters in this story suffer from being alienated from the community:

- Crooks is ostracized because of his race, living in a separate shabby house as a misfit.

- George also suffers from forced alienation because he takes care of the mentally disabled Lennie.

- Curley’s wife is another character suffering from loneliness. This feeling drives her to despair. She seeks the warmth of human relationships in the hands of Lennie, which causes her accidental death.

Isolation Quotes: Of Mice and Men

Now, let’s analyze a couple of quotes from Of Mice and Men to see how the author approached the theme of loneliness.

Guys like us who work on ranches are the loneliest guys in the world, they ain’t got no family, they don’t belong no place. Of Mice and Men , Section 1

In this quote, Steinbeck describes several dimensions of isolation suffered by his characters:

- They are physically isolated , working on large farms where they may not meet a single person for weeks.

- They have no chances for social communication and relationship building, thus remaining emotionally isolated without a life partner.

- They can’t develop a sense of belonging to the place where they work; it’s another person’s property.

Candy looked for help from face to face. Of Mice and Men , Section 3

Candy’s loneliness on the ranch becomes highly pronounced during his conflict with Carlson. The reason is that he is an old man afraid of being “disposed of.” The episode is an in-depth look into a society that doesn’t cherish human relationships, focusing only on a person’s practical utility.

I never get to talk to nobody. I get awful lonely. Of Mice and Men , Chapter 5

This quote expresses the depth of Curley’s wife’s loneliness. She doesn’t have anyone with whom she would be able to talk, aside from her husband. Curley is also not an appropriate companion, as he treats his wife rudely and carelessly. As a result of her loneliness, she falls into deeper frustration.

✍️ Essay on Loneliness and Isolation: Topics & Ideas

If you’ve got a task to write an essay about loneliness and isolation, it’s vital to pick the right topic. You can explore how these feelings are covered in literature or focus on their real-life manifestations. Here are some excellent topic suggestions for your inspiration:

- Cross-national comparisons of people’s experience of loneliness and isolation.

- Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality among the elderly.

- Public health consequences of extended social isolation .

- Impact of social isolation on young people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Connections between social isolation and depression.

- Interventions for reducing social isolation and loneliness among older people.

- Loneliness and social isolation among rural area residents.

- The effect of social distancing rules on perceived loneliness.

- How does social isolation affect older people’s functional status?

- Video calls as a measure for reducing social isolation.

- Isolation, loneliness, and otherness in Frankenstein .

- The unique combination of addiction and isolation in Frankenstein .

- Exploration of solitude in Hernan Diaz’ In the Distance .

- Artificial isolation and voluntary seclusion in Against Nature .

- Different layers of isolation in George Eliot’s Silas Marner .

- Celebration of self-imposed solitude in Emily Dickinson’s works.

- Buddhist aesthetics of solitude in Stephen Batchelor’s The Art of Solitude .

- Loneliness of childhood in Charles Dickens’s works.

- Moby-Dick : Loneliness in the struggle.

- Medieval literature about loneliness and social isolation.

Now you know everything about the themes of isolation, loneliness, and alienation in fiction and can correctly identify and interpret them. What is your favorite literary work focusing on any of these themes? Tell us in the comments!

❓ Themes of Loneliness and Isolation FAQs

Isolation is a popular theme in poetry. The speakers in such poems often reflect on their separation from others or being away from their loved ones. Metaphorically, isolation may mean hiding unshared emotions. The magnitude of the feeling can vary from light blues to depression.

In his masterpiece Of Mice and Men , John Steinbeck presents loneliness in many tragic ways. The most alienated characters in the book are Candy, Crooks, and Curley’s wife. Most of them were eventually destroyed by the negative consequences of their loneliness.

The Catcher in the Rye uses many symbols as manifestations of Holden’s loneliness. One prominent example is an image of his dead brother Allie. He’s the person Holden wants to bond with but can’t because he is gone. Holden also perceives other people as phony or corny, thus separating himself from his peers.

Beloved is a work about the deeply entrenched trauma of slavery that finds its manifestation in later generations. Characters of Beloved prefer self-isolation and alienation from others to avoid emotional pain.

In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World , all people must conform to society’s rules to be accepted. Those who don’t fit in that established order and feel their individuality are erased from society.

- What Is Solitude?: Psychology Today

- Loneliness in Literature: Springer Link

- What Literature and Language Tell Us about the History of Loneliness: Scroll.in

- On Isolation and Literature: The Millions

- 10 Books About Loneliness: Publishers Weekly

- Alienation: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Isolation and Revenge: Where Victor Frankenstein Went Wrong: University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- On Isolation: Gale

- Top 10 Books About Loneliness: The Guardian

- Emily Dickinson and the Creative “Solitude of Space:” Psyche

- Share to Facebook

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Have you ever loved? Even if you haven’t, you’ve seen it in countless movies, heard about it in songs, and read about it in some of the greatest books in world literature. If you want to find out more about love as a literary theme, you came to the right...

Death is undoubtedly one of the most mysterious events in life. Literature is among the mediums that allow people to explore and gain knowledge of death—a topic that in everyday life is often seen as taboo. This article by Custom-Writing.org will: 💀 Significance of Death in Literature Why is it...

Wouldn’t it be great if people of all genders could enjoy equal rights? When reading stories from the past, we can realize how far we’ve made since the dawn of feminism. Books that deal with the theme of gender inspire us to keep fighting for equality. In this article, our...

What makes a society see some categories of people as less than human? Throughout history, we can see how people divided themselves into groups and used violence to discriminate against each other. When groups of individuals are perceived as monstrous or demonic, it leads to dehumanization. Numerous literary masterpieces explore the meaning of monstrosity and show the dire consequences of dehumanization. This article by Custom-Writing.org will: 👾 Monstrosity:...

Revenge provides relief. Characters in many literary stories believe in this idea. Convinced that they were wronged, they are in the constant pursuit of revenge. But is it really the only way for them to find peace? This article by Custom-Writing.org is going to answer this and other questions related...

Is money really the root of all evil? Many writers and poets have tried to answer this question. Unsurprisingly, the theme of money is very prevalent in literature. It’s also connected to other concepts, such as greed, power, love, and corruption. In this article, our custom writing team will: explore...

Have you ever asked yourself why some books are so compelling that you keep thinking about them even after you have finished reading? Well, of course, it can be because of a unique plotline or complex characters. However, most of the time, it is the theme that compels you. A...

The American Dream theme encompasses crucial values, such as freedom, democracy, equal rights, and personal happiness. The concept’s definition varies from person to person. Yet, books by American authors can help us grasp it better. Many agree that American literature is so distinct from English literature because the concept of...

A fallen leaf, a raven, the color black… What connects all these images? That’s right: they can all symbolize death—one of literature’s most terrifying and mysterious concepts. It has been immensely popular throughout the ages, and it still fascinates readers. Numerous symbols are used to describe it, and if you...

The most ancient text preserved to our days raises more questions than there are answers. When was The Iliad written? What was the purpose of the epic poem? What is the subject of The Iliad? The Iliad Study Guide prepared by Custom-Writing.org experts explores the depths of the historical context...

The epic poem ends in a nostalgic and mournful way. The last book is about a father who lost his son and wishes to make an honorable funeral as the last thing he could give him. The book symbolizes the end of any war when sorrow replaces anger. Book 24,...

The main values glorified in The Iliad and The Odyssey are honor, courage, and eloquence. These three qualities were held as the best characteristics a person could have. Besides, they contributed to the heroic code and made up the Homeric character of a warrior. The Odyssey also promotes hospitality, although...

‘A painful absence all of the time’: the best descriptions of loneliness in literature

The last word, our series about emotions in books, focuses on depictions of isolation this month, from a memoir of grief to Sam Selvon’s Windrush chronicle

L onely, as words go, is a bit of a loner. As the critic Christopher Ricks writes, it pleasingly has “only” one rhyme, and no real synonyms. After all, being alone and being lonely are quite different things. For all this, poets and writers, from Audre Lorde to Philip Larkin, have made much of loneliness, drawn to the challenge of bringing us close to an emotion whose very nature is to stay at a distance.

Some lonely renderings turn out to be a bit of a sham. Records show that when Wordsworth “wandered lonely as a cloud”, his sister Dorothy was strolling companionably beside him, and she liked the daffodils too. Thoreau’s standing as the poster-boy of solitude, living “alone” and “Spartan like” by Walden Pond, starts to unravel when one actually reads his book, which contains a hefty chapter on “Visitors”. (The fact that Thoreau’s mum probably helped out with his laundry has also – maybe unfairly – raised a few eyebrows.)

It is, of course, perfectly possible to feel lonely in the company of others. “Loneliness”, as Olivia Laing writes, “doesn’t necessarily require physical solitude, but rather an absence or paucity of connection”. Her Lonely City is a powerful account of the loneliness explored and expressed by writers ranging from Alfred Hitchcock to Billie Holiday, combined with Laing’s own experience as a “citizen of loneliness”: “I often wished”, she writes, “I could find a way of losing myself altogether until the intensity diminished”.

Loneliness may be a condition that’s tricky to categorise but it is also, in Laing’s words, “difficult to confess”. Indeed, loneliness’s favourite companion seems to be shame. One of the many beauties of Kent Haruf’s small-town love story, Our Souls At Night, is the way in which his heroine breaks this seeming taboo, surprising her neighbour with an unconventional proposal, not of marriage, but of a kind of lo-fi pyjama party. “I’m lonely”, Addie candidly states. “I think you might be too. I wonder if you would come and sleep in the night with me. And talk”.

after newsletter promotion

For some, such as Gail Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant, loneliness is a lived atmosphere, a kind of chronic condition. For others, it comes from a tectonic shift – a sudden loss or bereavement. As Juliet Rosenfeld writes in her memoir, The State of Disbelief, the painful force of her husband’s death made her feel as if she’d been captured by an unseen captor: “I learnt quickly that to protest would make no difference, and choice-less, I submitted to this saboteur with no prospect at all of release or freedom. I believed for a long time that I would never feel differently. I felt a painful absence and loneliness all of the time .”

“We read to know we are not alone”, as C S Lewis famously didn’t say (the line belongs to his on-screen persona in Shadowlands). So it is a sad irony that books which might best provide company nearly didn’t see the light of day. Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness was banned, after its first publication, for more than 30 years, accused of promoting “unnatural practices between women”. Because of that judgment, many readers missed an encounter with the beauty of the novel’s prose, its tender account of the heroine as she reflects on her childhood home. She dreams of “the scent of damp rushes growing by water; the kind, slightly milky odour of cattle; the smell of dried rose-leaves and orris-root and violets”, and knew “what it was to feel terribly lonely, like a soul that wakes up to find itself wandering, unwanted, between the spheres”.

This sense of loneliness as a kind of between-ness, an uncharted territory, is movingly captured in Sam Selvon’s 1956 novel, The Lonely Londoners. This Windrush chronicle charts the trials of those arriving at Waterloo from the West Indies, as they struggle to navigate the “unrealness” of London. Selvon’s hero, Moses Aloetta, becomes, over time, the reluctant guide to this latter-day Waste Land. Selvon leaves us with Moses’s lyrical and allusive understanding of the city’s “great aimlessness”. Standing on the banks of the Thames, he conjures a vision of a world in which we are all, in the end, alone together:

As if … on the surface, things don’t look so bad, but when you go down a little, you bounce up a kind of misery and pathos and a frightening – what? He don’t know the right word, but he have the right feeling in his heart. As if the boys laughing, but they only laughing because they ’fraid to cry.

- The last word

- William Wordsworth

- Olivia Laing

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- Essay Editor

The Theme of Loneliness in Life in Literature

1. introduction.

This is a classic work and includes a variety of aspects that aid our understanding of the issues surrounding the theme of loneliness. In order to understand fully the issues and the impact that loneliness has towards the ending of life, we have posed several questions about the nature of loneliness and its effects. This has been used as a guide, helping with our understanding of the themes in the book and answering these questions by providing possible solutions and examples of the impact towards the issue raised. This work acknowledges that to fully understand the issues of loneliness, one has to consider what loneliness actual is and its effects. Our understanding of loneliness is the state of the mind being isolated from others, mostly caused by the absence of a person in which a deep emotional bond has been formed i.e. a friend or relative. This is resolved and explained as, a state of being alone, or the feeling that one is alone, but it can be noted that to be alone, is not the same as feeling alone. From this it is possible to suggest that loneliness is purely a state of mind, a feeling, and at that the individual can endure the feeling of loneliness even when surrounded by others, for he may have lost someone he had a bond with, or the company of others does not substitute for that person. Throughout the book there are various types of loneliness that affect the characters and this has a large impact towards the issues of the character's and their quality of life. This aspect raised was something considered in our questions and was very well explained with responses and examples in the instance where the character Candy is deeply saddened by the loss of his life long friend and companion, a dog. This is the pet's absences that has cause a deep bond to be broken and has left him feeling that he has nothing to live for. Lennie, also experiences an intense form of loneliness, firstly by the separating from his close friend and companion George, who is his aid and guidance and secondly to the knowledge of the death of Curley's wife, where his fear and confusion ignites anger from the others and force him to run and hide from them. Lennie's fears for his life lead to the desperation and mirroring of George's situation of how he would cope alone. These are quite profound examples, which illustrate, the effects and the causes of loneliness, posing a view that some loneliness begins through loss and that it has the potential to be damaging to someone, especially if what is known as a cure, is unattainable.

1.1. Definition of loneliness

Seeing as loneliness is not simply a "state of being alone", it is necessary to explore the definition of loneliness. When reading through books, the typical definition of loneliness will be altered, as will with each individual who is asked. There are as many definitions as there are experiences of loneliness, for each person's experience is different. However, generally speaking, loneliness is "the unpleasant experience that occurs when a person's network of social relations is deficient in some important way, either quantitatively or qualitatively". This may occur for several different reasons: through isolation forced on an individual (i.e. as a punishment), by the person shunning society because they believe that they are not accepted, or it may occur despite a person being surrounded by others. This last point is important, for it must be made clear that loneliness is not the same as being alone. There are many situations in literature, particularly Shakespeare, where characters are thrust into circumstances where they are "alone", but this does not necessarily mean they are lonely. For example, there is a great misunderstanding in the final scene of Hamlet, where Gertrude speaks of Ophelia's death by saying that she climbed into a willow tree and the branch broke and "thus her absence is discover'd". This suggests that Ophelia was alone when in fact, she was surrounded by a King, two courtiers, and a Queen, but the manner of her death and burial was so ambiguous that nobody knew what had become of her. This situation was one of too much grief for Ophelia's loved ones, too embarrassing to attempt to resolve, and it led to them removing her from their thoughts and thus from their lives. Ophelia was psychologically cut off from the society she had known, despite the close proximity of others. This situation was the catalyst to Ophelia's loneliness, and it is possible to be any one of Ophelia's loved ones who feels such grief that they too become cut off from society, or even the modern-day individual who may undergo a change in career or move to a new city and lose contact with friends and relatives. There are many ways to become cut off from society, and it is not always through choice.

1.2. Importance of exploring loneliness in literature

Loneliness is a very important theme in literature. Regardless of what the actual situation of the author, a feeling of being alone has an effect on everyone. Those who are alone do not always feel lonely, and those who are lonely are not always alone. It is a feeling that can be felt during good times and bad, by rich and poor, young and old, in far off places or close to home. It is a feeling that has no true definition, but to the individual who feels it, it is all too real. And this is what often makes the theme of loneliness so consuming in many great works of writing. Because it is a feeling that can have many faces across all of humanity, there is a great depth of material that can be written on the subject. This is why this theme is often found at the center of the human condition, which is a main focus of "The Theme of Loneliness in International Literature". At this point, the reader may be wondering why read about the sadness of others when one could pick a more cheery topic to hold their interest? The answer is simple. Any person who reads for more than just the idle passing of time is always studying the same thing: themselves. And self-study cannot go very far without learning from others of their own kind. The stories and struggles of other human beings are a mirror to our own. If we look closely enough, we can always see some part of ourselves. And so, readers will often find strength in reading about another person who is in the same state as they are in at the present. This is why there is always an odd fascination with tragic stories of doom and gloom. This too is a form of self-study by learning what not to do by observing the mistakes of others. Often times in the study of the human condition, people wish to find out why others act the way they do. Global work is most often a product of its age and the mental state of its author. In reading the work and observing the artist's life, one often attempts to draw parallels between the two. Here is a good example of where one can have a deeper understanding of someone else through shared experiences. And so, a person who is learning about loneliness may find great comfort in reading about a single person who has conquered that same form of loneliness. They may then draw hope from a story and strive to find the same end. And so, through these methods of self-study, a person can learn a great deal from the written experiences of others. Any reader will undoubtedly find characters who are alone in their situation is a reflection of themselves, and this is one of the deepest roots of the human condition.

2. Loneliness in Classic Literature

Throughout the landscape of literature there have been innumerable works centered around the theme of loneliness. Many authors use this theme to better illustrate the emotions and workings of a character. This is the case with Moby Dick by Herman Melville, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, and The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. In each of these novels, the main character is so engulfed with a feeling of loneliness and alienation it affects the way they act and view the world around them. In Moby Dick, Ishmael is the only character that is developed throughout the novel. Ishmael is a lonely soul with a strong need for companionship. His feelings of despair started when his close friend Queequeg became very ill and Ishmael presumed he was going to die: "With much dealing, and so some light..." (Melville 393). Illness and the devils are vague terms that lead the reader to believe that Queequeg's bout with death was brought on by something darker than just a common illness. This greatly troubles Ishmael for he has no one else in the world to turn to for companionship at this time. He then starts to feel alone when aboard the Pequod. At the masthead, he ponders his reason for signing onto such a perilous journey and comes to the conclusion that: "...a mighty whaling mission was something wherein a number of men did a number of things comprehensive of the one purpose, in various relays and if revalves; which was done on the same thing, that thing was to kill whales..." (Melville 406). Ishmael feels that his noble aims and deeds failed because they were all done for different purposes, his being to get companionship through cooperation on a whaling voyage. His feeling of loneliness is a driving force that causes Ishmael to constantly question himself and his rationale for the situations he is in.

2.1. Loneliness portrayed in "Moby-Dick"

In "Moby-Dick", Ishmael is a very lonely character. His loneliness is a result of many things. He has lost faith in humanity, and it is also suggested that he has lost faith in God. Ishmael also feels separate from the greater masses of humanity, feeling that he is on a different plane of existence to the common man. Ishmael also feels isolated from the men that he is to serve with on the whaling ship, as he does not fit the typical image of a harpooner. The 30th chapter of "Moby-Dick" titled "The Pipe" gives an introduction into the loneliness of Ishmael. Ishmael has ascended into the main-top of the ship, a place where he is completely isolated from anyone else. At this point, Ishmael observes Queequeg through the lens of the main-top. He comments that Queequeg is "the savages of good nature" and wishes that he can be like him. He then gets onto the subject of humanity and his own place within mankind. This is the first indication of his loneliness, and it is a recurring theme throughout the book. Ishmael's feelings of loneliness often drive him to contemplate suicide, a method of escape from his loneliness. This is first hinted at in chapter 10 when Ishmael is examining Queequeg's collection of spears and decides against killing himself. The idea receives consideration again when the ship is away at sea and Ishmael decides whether or not it is better "To fly to others that we know not of" and to "drown" in the ocean. Ishmael's contemplation of suicide picks up pace when he is introduced to the gloomy and solemn first mate of the ship, Captain Ahab. Ishmael feels the darkness of Ahab and decides that it would be best if he "flies from the world's wisdom". This is a logical conclusion of his thoughts as Ishmael feels too wise to simply follow Ahab into what he feels is doom, and does not want his parting to be "drowned in a foul mist of fire". This progression eventually leads to Ishmael seeking an escape through joining a whaling ship as a means to break from the ever-tightening grip of his loneliness.

2.2. The theme of isolation in "Frankenstein"

Due to the remote circumstances of his creation, the being is left in isolation from society and his immediate surroundings. It is the isolation from society and the relationship with a creator that twists the hope that leads him through this trying time into an experience of increasing anger, vengeance, and eventually his downfall. This penchant for isolation is not exclusive to the being. Robert Walton shares a similar form of isolation that the being endures. Like the being, this isolation allows him to find solace in gaining knowledge, albeit the ice-entrapped ship is a more fitting place to gain knowledge than the pursuit of forbidden knowledge in the creation of life. Although the form of the isolation and the motivations to gaining knowledge differ, the parallel between the two instances allows the being to feel a somewhat affiliation with Walton, and it is this affiliation that leads him to agree to tell his story to the ship's captain. The methodology and personality differences between Walton and the being represent the two outcomes of being isolated from the rest of humanity in search of knowledge and companionship. Like the being, the pursuit of knowledge in solitude leads to an experience of sorrow and a loss of hope. This is exemplified by Walton's words at the end of the story when the being asks that he continue to strive for more, which he later admits was a great mistake.

2.3. The lonely existence of Jay Gatsby in "The Great Gatsby"

Gatsby's is the tale of a tortured man who threw away his one real chance at happiness and love of self to follow a meaningless dream. At his best, Gatsby is a kind of heroic figure: a man who has been through war and lived, through poverty, and has finally managed, through hard work and ingenuity, to achieve a level of material success unmatched by even those who had been born into American aristocracy. But Gatsby's passage to the world of the very rich is quick and easy; he is for instance able to support himself with no visible means of support, by the time he meets Daisy. He becomes a bootlegger to attain quick money; in Latham's term, a criminal entrepreneur. He buys the mansion solely to be near Daisy; even though she now lives just across the bay with her husband. Gatsby's fire of love is doused when he is unable to repeat the past, and the dream of love and happiness of he and Daisy being together dies, in accordance to Nick because Gatsby "had been full of the idea so long, dreamed it right through to the end, waited with his teeth set, so he could act at the moment, he f***d up an attempt that was unsuited to him". If the American dream is anything at all Gatsby's wish is a crude and hopeless effort to achieve it. He will stop at nothing in order to attain the love of Daisy, an apprehension best exemplified by Nick's recollections of a conversation with Gatsby in which he wanted to fix Nick up in a deal of "way you can pick up a little money on the side".

3. Loneliness in Contemporary Literature

The social isolation of today's individuals is a universal theme in contemporary literature. It is a literary effort to benchmark the social changes apparent in Western societies from the 1950s to the turn of the century. The increasing political and media emphasis on the family at this time has, according to Maxine Blyton in The Times, "pushed single people to the margins," resulting in social disconnectedness manifesting in unprecedented individualism, decreased concern for others, and increased loneliness and unhappiness. This is reflected in contemporary fiction through the exploration of individual alienation and its effect on mental states, and while such themes are not deemed exclusive to contemporary literature, it is the focus on the individual’s place in the world and sense of identity that distinguishes these works from their modern counterparts. Oliphant is a changed woman with strained social skills and a traumatic past. We learn of her university days where an event has ostracized her from her peers, and her dealings with her colleagues do little to end her isolation as she is socially awkward and perceived as strange. Throughout the novel, Eleanor feels a strong yearning to be "normal" and uses this as a reference to achieve a sense of belonging she has never known. Her chance meeting with Raymond is the catalyst for change in the novel, and though the relationship brings new experiences and feelings of joy to Eleanor, it is not without initial frustration and clashes due to their contrasting social skills and class. Through the character of Eleanor, Honeyman wonderfully portrays the sad and often confused state of those who suffer from long-term isolation. He exposes the harsh reality that, despite a genuine desire to connect with others, solitary individuals are often ill-equipped with social skills and subsequently act in ways that are not conducive to forming lasting relationships. This, in turn, leads to further rejection and deepens the alienation felt. Eleanor's feelings of inadequacy and despair are summed up in an insightful statement: "I suppose one of the reasons I'm on my own is that I have little idea of how to form relationships." In his novel, Honeyman sends a powerful message about the desperate effects of loneliness and the innate human desire to belong.

3.1. The exploration of loneliness in "Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine"

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman is a novel about a woman called Eleanor Oliphant who lives a life of loneliness. It covers her working hours and her time spent outside of her home. Honeyman explores the theme of severance through Eleanor's childhood-inflicted pain, her intrinsic barriers, and society's failure to assimilate with the unknown or atypical. Eleanor's childhood is revealed to have been a significant contributor to her state of loneliness and detachment from society. It alludes to several key incidents that have shaped her into the person she is in the present day. She explains to the reader that her father put her into care when she was young, as he claims he could not attend to her needs. This is one incident that has lasting repercussions on her current state. Though an innocent child, Eleanor was branded as an atypical and problematic figure. This separation from her family also serves as an origin for her feelings of severance, which become apparent in her later years. This abandonment had also led to Eleanor being brought up in care. Eleanor describes the experience as unpleasant and at times neglectful. This would contribute further to her feelings of loneliness, as she lacked significant contact with any loving figure, and she was further branded as atypical due to the fact she received "input" from a social worker. Overall, her father's decision and the fact he gave no logical explanation or apology serve as the foremost origin of her loneliness, for it was the point at which she was separated from her family and branded as a societal anomaly. This sense of loneliness continues throughout the novel, and Eleanor finds that she cannot identify with anyone and feels completely averse from others due to her strange upbringing.

3.2. The theme of solitude in "Norwegian Wood"

Set in the late 1960s, Norwegian Wood illustrates the story of Toru Watanabe, a young student in Tokyo. The novel is a reminiscence of his past, particularly his love life. One significant event that affected him greatly is the death of his close friend, Kizuki. They were both 17. Kizuki committed suicide for no apparent reason when they were in the third year of high school. The death drove Watanabe to befriend Kizuki's girlfriend, Naoko, and Nagasawa, the boyfriend of one of his high school classmates. This new group of friends decided to visit a reclusive farm in the countryside, where Naoko would subsequently choose to live in solitude due to her inability to cope with Kizuki's death. These events and a growing romance between Watanabe and Naoko lead to a sequence of situations and emotions that ultimately resulted in Watanabe's psychological transformation and the commencement of his adulthood. The theme of solitude is evident primarily through Naoko's character. Toru Watanabe often finds himself lost in thought about her, increasingly so as he finds out that her condition worsens. After Kizuki's death, she is unable to cope with his absence and soon begins losing her mental stability. Her move to the sanatorium represents her newfound state of mind: a blurred world in which she feels detached because she continues to think of living in a world with Kizuki at the meadow. The setting of the sanatorium and later a secluded mountain retreat represents her idea of finding a place to belong and a place that is cut off from the rest of the world. Her suicide at the end of the story and the metaphorical death of her character, in which she loses touch with Watanabe, the only one she truly loved, signifies the ultimate visual of Naoko's long journey in seeking a place where she feels at ease, finally reaching a point in which she seeks it in death. This is by no means a positive statement, but through Naoko, Murakami effectively illustrates the inner conflict that an individual faces when they are feeling detached and seeking a place to belong, often with contrasting results.

3.3. The isolated characters in "The Catcher in the Rye"

The novel "The Catcher in the Rye" has been described as one of the best novels of its time. Contrary to belief, it is not just an account of an unusual teenager in New York City but also considered a study of a teenager, an analysis of a boy who is lost in adolescence and literally on the edge. Through his red hunting hat, the ducks in the pond, the Museum of Natural History, and his wish to be the "catcher in the rye," Holden battles with the fear of change and the unknown. Throughout the novel, we see Holden Caulfield, the protagonist, demand the companionship of those he encounters. We also see him shying away from any opportunity of integrating into society and following the mainstream. This behavior can result from a fear of unknown territory. It has been said that this state of mind is due to his lack of confidence in himself and the world around him. Holden sets standards for his peers and categorizes them. This is a cause of the "phoniness" which he constantly refers to. He believes that everyone is out for themselves and can care less about him. One of the prime examples of his behavior is shown when Stradlater, Holden's dorm mate at Pencey Prep, is getting ready for a date with Jane Gallagher, an old friend of Holden's. He remarks, "You're playing the record too damn fast," I said. "That's a guy's jacket, not a goddamned tuxedo." I didn't want to hurt his feelings, but it was more than I could take. (p. 29) This comment leads to a fight sparked by Stradlater who does not appreciate Holden's attempt to critique and improve his appearance.

4. Conclusion

The enduring relevance of the theme of loneliness in literature has led in recent years to a plethora of critical attention from a broad range of theoretical stances. Whether the analysis has grown out of existentialist, Marxist, structuralist, feminist or post-modernist theory, a great deal of this material shares some of the very assumptions about the nature of loneliness and its human significance that literature itself puts forward. However, in one rather important sense, criticism has been unable to match the understanding of loneliness elaborated through great works of fiction, poetry or drama, because it has often had to approach the study of lonely states in ardour to decode their cultural, social, political or personal meanings, thus at times the singular experience of loneliness as such has been overlooked. It is true that deeper analysis of the lonely lifestyle can in certain instances yield important insights, for a narrative of loneliness is invariably a narrative of disjuncture, often between self and society, self and the natural world, or conflicting selves; and a full critical understanding of this disjuncture can only further our understanding of the human condition. Discussing loneliness in terms of "isolation" or "alienation" is the thematic criticism stock-in-trade. However, the literary representation of lonely states is itself often a tacit critique of such modes, for in giving literary form to what is in essence a wordless experience of longing or absence, it holds up to the fictional world and its readers a vision of the connectivity its protagonist has lost, or yearns for. At its best, this can act as an allegory for the disjuncture of the modern age or some part of the human situation as the inquiring reader recognizes the emptiness of a certain character’s place or senses that in constructing a brave new world, man has too often lost something precious. A case in point is Wordsworth's famous evocation of the solitary reaper "beholding her on solitary highland". The poet overhearing the girl's song finds it haunt him long after he has wandered away and can never again listen to a similar strain from the vales without an image of that one girl. It is a touching snapshot of a moment shared with an anonymous figure that has reverberated powerfully within the writer, and it has proved so evocative a scene that generations of English students have been asked to imagine just who the highland lass was. Yet the cold facts of the poem are that the poet no more speaks with the girl nor returns to that dale and in giving the episode this much poignancy Wordsworth has inadvertently created a sense of loss and absence.

4.1. The enduring relevance of the theme of loneliness in literature

In tackling the endurance of the theme of loneliness in literature, it is paramount that the analysis is not only restricted to texts penned decades or centuries ago. The enduring quality of literature has meant that older texts have never ceased to be re-read, but it has also created an impetus for the production of new texts which revisit old themes in the modern context. Through the exploration of both older and newer works, one can see that the theme of loneliness has not only endured, but evolved over time. In the modern globalised world, the melting away of previous social structures has given way to new types of loneliness. This is illustrated in Ben Okri's novel Astonishing the Gods, where the relocation of an African man to an unspecified megacity in which he is unable to converse the local language brings about a profound sense of alienation and loneliness. Literature criticism often focuses on an interpretation of a text in terms of its social and historical context. While such an approach invariably sheds light on the work in question, it is arguable that the critical value of a text can also be determined by its ability to transcend the context in which it was created. If we take the view that some themes are pertinent regardless of the date of their consideration, then the works which deal with these themes in a profound yet historically transcendent manner must be considered to have an enduring relevance. It can be argued that texts whose themes are only relevant to the period or context in which they were written are of limited critical value, as they will become increasingly difficult to understand for those without the necessary historical knowledge. An enduring theme, however, can be appreciated by readers from a wide variety of backgrounds and eras. The theme of loneliness is clearly transcendent: as long as humans exist, there will be the possibility for some to feel cut off from others.

4.2. The impact of loneliness on readers' understanding of the human condition

Introduction: When readers are exposed to the lonely characters that inhabit the world of literary fiction, there is an empathetic reaction which inspires the reader to not only feel for the character, but to also reflect on their own life and the world around them. This inevitably leads to an exploration of the human condition, and an inquiry into the true 'nature of things'. It is a difficult task to pinpoint the intrinsic understanding that is developed about the human condition through reading about lonely characters, but one can identify the various ways in which an understanding has been developed and the effect that it has had. Sympathy and Empathy for the Human Condition: When one is reading about a lonely character who is experiencing an emotional state which resonates with the reader's own emotional state, the reader will feel a sympathetic emotion. This sympathy often arises from an empathetic reaction to the emotions of the character. Empathy for another human being naturally leads to reflection on one's own self. The emotions experienced by the character become a mirror which reflects one's own life, and one's own emotion. In giving the reader a heightened self-awareness and understanding of their own emotions and the relationship between the two, empathy for a lonely character draws a strong parallel between the circumstances of the character and the circumstances of the reader. Futility: As the reader is challenged by the lonely characters of Steinbeck or the tragic isolation of Melville's Bartleby, there is often the realization that the characters' situation is without hope. It is here that one is exposed to the futility of the human condition and its struggle. This realization has a profound effect on many readers, leading to an understanding about the nature of life and some of its harsher realities.

Related articles

Análise da expressão "fica sobre" no contexto das relações de poder na literatura contemporânea.

1. Introdução A expressão "fica sobre" tem sido objeto de estudo no contexto das relações de poder na literatura contemporânea, devido à sua relevância na construção de significados e na representação de dinâmicas hierárquicas e submissão. Essa análise visa lançar luz sobre as diferentes interpretações e usos dessa expressão, bem como seu papel na negociação de poder entre personagens e grupos sociais. Ao compreender a complexidade desse fenômeno linguístico, espera-se contribuir para uma compr ...

Análisis de una bibliografía crítica sobre la evolución de la literatura latinoamericana contemporánea

1. Introducción Este trabajo pretende ser una introducción al análisis de un campo nuevo dentro de la bibliografía general sobre la literatura latinoamericana contemporánea: los estudios comparativos. Dichos estudios resultan ser en realidad comparativos no exactamente porque procuren establecer categorías generales de análisis, sino porque en su gran mayoría recurren a las expresiones literarias de los distintos países latinoamericanos para "ilustrar" y a veces contrastar esos enunciados gener ...

Análisis de la bibliografía crítica sobre la obra de Gabriel García Márquez

1. Introducción a la obra de Gabriel García Márquez En el presente trabajo de tesis se analiza la figura de Gabriel García Márquez. Se realiza un recorrido por su vida y se examina la biografía crítica de su obra, siguiendo un planteamiento cronológico. El texto está estructurado en dos partes, correspondiendo la primera a la labor crítica realizada durante la vida del escritor. Se efectuará un análisis de sus relaciones con el ambiente literario y político colombiano y sudamericano, centrándos ...

Themes and Symbolism in Ivo Andric's Novel "Prokleta Avlija"

1. Introduction to Ivo Andric and His Work The life and work of Ivo Andric are certainly important for the study of literatures of the former Yugoslavia. His symbolic novel, Prokleta avlija, introduces both students and the wider public not only to his significant contribution to the multilingual Yugoslav literary world but also to the cultural tapestry of Adamant's Balkans. Traditionally, Andric is well known as an "observer of the Serbian people," and Prokleta avlija is his masterpiece, beaut ...

An analysis of Albert Camus' existentialist themes in the novel 'La Chute' (The Fall)

1. Introduction to Albert Camus and 'La Chute' The French-Algerian writer and Nobel Prize winner, Albert Camus (1913-1960), is one of the best-known and most widely read 20th-century authors. His novels, such as L'Étranger (The Outsider, also known as The Stranger), Lettres à un ami allemand (Letters to a German Friend, published posthumously), and La Peste (The Plague), have been translated into many languages, and his journalistic and philosophical essays have been included in over a hundred ...

The Importance and Impact of Bibliographic Research in Academic Studies

1. Introduction Bibliographic research is a decisive and indispensable factor for the writing of academic work. The very word "research" ends up orbiting a multitude of investigative possibilities, not necessarily related to the acquisition of previously known and treated information. Conceptually, it is taken to look for a relationship, factor, process, system, product or any other form of phenomenon investigated. Carrying out bibliographic research allows the student to develop critical and r ...

Análisis crítico sobre temas de justicia social en la literatura contemporánea

1. Introducción Durante el siglo XIX, la corriente más importante de la filosofía moral anglosajona, apenas ilustró un cambio científico, pronto llamado la teoría de la evolución. La misma mantenía estrechas relaciones con individuos selectos de la especie humana (Teoría de la Evolución Natural) y había adoptado esa teoría como solución a múltiples problemas políticos y sociales. Así, al considerar especialmente dignos de preservarse y reproducirse a aquellos que son mejor adaptados a las cambi ...

The Importance of Identifying Research Gaps in Academic Studies

1. Introduction Both students and faculty researchers are expected to engage in academic research that offers something demonstrably new and important to the body of literature investigating the subject matter at hand. The pressure to "say something new" often seems more urgent to academic researchers than it actually is, but the fact remains: all too often, important research gaps are overlooked. Academic research should contribute to the field by answering pressing questions. Therefore, this ...

The Stories Women Tell of Loneliness

E mily Dickinson is American literature’s famed recluse. “Silence is Infinity,” she wrote—and her solitude was generative. Loneliness, as she figured it , was “the Maker of the soul.” But what about women today? Are they relishing their solitude? In May 2021, preliminary research findings were presented at the American Heart Association’s Epidemiology, Prevention, Lifestyle, and Cardiometabolic Health Conference that suggested social isolation and loneliness were each associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women.

As I scrolled past this news, I found my copy of Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest novel, Whereabouts , which follows an unnamed narrator through a period of quiet desperation. The novel, spread over 40-something chapters and translated by Lahiri from her own Italian, features the mundane, uninspiring, and domestic. We see the narrator go on walks with a friend, sit alone, look at other people, speculate about their relationships with one another, ponder the nature of loneliness, engage with her elderly mother.

A similar thread of loneliness weaves through another recent novel, Natsuko Imamura’s The Woman in the Purple Skirt , which has been translated from the Japanese by Lucy North. Imamura’s is a tale of isolation punctuated by slapstick humor. The nameless narrator is a deeply confounded, lonely, aimless person. She is also a stalker. Seated at the fringes of society and her workplace, she obsessively watches a colleague in a purple skirt, betraying no hint of guilt at stalking this near stranger. That the narrator’s unnerving internal monologue also happens to be very funny at times only makes it more interesting.

I found the anonymity, obsession, and absurdity of Imamura’s novel and the peevish, circuitous, and perambulatory tone of Lahiri’s Whereabouts echoed in the BBC Three show Fleabag . As an angry and dazzlingly intelligent young woman, Fleabag ’s eponymous protagonist is certainly more glamorous and gregarious than Lahiri’s and Imamura’s central characters, but she, too, is a profoundly feminine portrait of bitter loneliness. “Women are born with pain built in,” a character asserts in Fleabag ’s Emmy-winning second season. “We carry it within ourselves throughout our lives. Men don’t. They have to seek it out.” We see the utter loneliness of the character Fleabag, whose two closest companions—her mother and her best friend—have died. She is suffering from a lack of attention.

Unlike Emily Dickinson, all three of these central characters are nameless (Imamura’s calls herself “the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan,” while Lahiri’s is at times addressed as “Signora”) and none of them has much appetite for being by themselves. Reading Whereabouts and The Woman in the Purple Skirt during the summer months, I found myself haunted by an old, familiar loneliness, made worse by my fears that it is a sadness particular to certain women.

For each of these three characters, one emotion is central: a kind of melancholy depicted as unique to women, transferred as if from centuries of repression, loneliness, and being thoroughly misunderstood. Sometimes the sadness takes second place to the unending drama of their lives, but mostly it is their primary experience. The three of them are restless, prone to snooping, and out of place wherever they are. They yearn to be noticed, known, and loved. Fleabag offers the best zingers (“I want someone to tell me what to believe in, who to vote for, who to love, and how to tell them”), while the Signora and the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan carry their burdens quietly, marinating a soulful broth of melancholy in the face of their dejection.

By cataloging the variousness of loneliness, Lahiri captures the attention of readers living through yet another year of the pandemic, with most forms of usual communication circumscribed. Her narrator laments, “In spring I suffer. The season doesn’t invigorate me, I find it depleting.” Anyone who has been through a momentary dip in their lives will know what she is talking about. Similarly, on mortality: “For the past few days there’s been a strange sensation under the skin at my throat, something along the lines of an irregular palpitation. I only feel it when I’m sitting at home, reading on my couch. That is, when I’m most relaxed, when I’m expecting to feel at peace. It lasts for a few seconds, then passes.”

Beneath Lahiri’s prose lies the particular connection between her women characters and loneliness. The Signora is strung out and cut off from her cultural and historical milieu. As readers, we return to a familiar world in which the characters understand that loneliness is simultaneously a scourge as well as a blessing. If you get too much of it, you lose your mind; if you get very little of it, then, too, you lose your balance.

Lahiri employs stark imagery to evoke the Signora’s emotional state. Anyone who has ever been near the waters of depression knows what she is referring to. Her protagonist suffers from melancholy, is haunted by the burdens of seclusion, but is (secretly) hopeful for the future. When she is subjected to a litany of her mother’s aches and pains, she notes, “I fear I’m a terrible daughter who ignores her mother, whose fault is to be excessively alive.” Here, Lahiri gestures to existential angst, building on longing and loneliness as recurrent themes in her novels.

After a night out, Fleabag, played by the writer-actor Phoebe Waller-Bridge, sits on the stoop outside her father’s house. She looks him in the eye, telling him: “I have a horrible feeling I am a greedy, perverted, selfish, apathetic, cynical, depraved, morally bankrupt woman who can’t even call herself a feminist.” He smiles. “You get all that from your mother,” he says, bringing the night and the conversation to an end. The feeling of feminine loneliness is intensified here—made clear in Fleabag’s despondency, then exacerbated by her father’s suggestion that she inherited her worst traits from her mother, motioning towards a generational form of suffering.

Imamura’s narrator, meanwhile, is bereft in ways that are mysterious and subliminal. She imposes her emotions on the object of her obsession. “The Woman in the Purple Skirt sat down on the bench, a lonely little figure, and enjoyed the last few sips of the sports drink. Then she looked down at her lap and examined her nails. She really did remind me of Meichan, my old friend from elementary school.”

In these poignant depictions of lack, we can perceive elements of the depression, mental illnesses, and misery (now exaggerated by the pandemic) affecting many across the world. Imamura captures the texture of this malaise precisely:

But when I looked carefully, it was clear that what she felt inwardly didn’t match what she projected outwardly. She wasn’t actually enjoying being a part of it all—not in her heart. Even if her lips were smiling, her eyes were not. All the other cleaners had animated expressions on their faces, but she alone had a touch of sadness about her. She was forcing herself, trying to appear to be having fun so as not to dampen the mood.

As artists, Waller-Bridge, Imamura, North, and Lahiri know how to combine naked confessionalism and comic artifice to tap veins of hungry emotion—anger, fear, and, particularly, deep sadness. They are not averse to having their protagonists walk into conventional, potentially sentimental situations, or trudge that thin line between sanity and berserk obsession. The emotionality of their characters plays out in abrupt, uncomfortable ways. These are headstrong, independent women who know better than to have an emotional breakdown—and they do everything that they can not to give in, until they can’t.

While men are, statistically, more prone to suicide, it seems that women are more likely to suffer from depression. A 2009 study in the US notes: “By many objective measures the lives of women in the United States have improved over the past 35 years, yet we show that measures of subjective well-being indicate that women’s happiness has declined both absolutely and relative to men.” Building on this, studies by the WHO have highlighted that women disproportionately suffer from common mental disorders (depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints). Clinical depression—twice as common in women—was predicted to be the second leading factor in the global disability burden by 2020.

Loneliness contributes to, compounds, and pressurizes these burdens. Depression and sadness undercut connection, as we see in Whereabouts , when a restorative break at a friend’s vacant country house reinforces the loneliness of Lahiri’s narrator. The novel proffers a muted portrait of urban solitude marked by undercurrents of not-knowing, longing, and desolation.

The Woman in the Yellow Cardigan feels her isolation more sharply on her days off. The pace of Imamura’s fiction is sober but highlights a disquieting undertow even to the most slapstick of moments. With each passing chapter we see a new layer to the narrator’s loneliness, revealing how strangely isolated she is, creating a patina of distress.

These writers know how to combine naked confessionalism and comic artifice to tap veins of hungry emotion.

The narrator makes disconcerting asides, like:

I considered all the hotel shampoo she could have availed herself of at absolutely no charge. And not only shampoo: conditioner, body wash, bars of soap. … I knew that nearly all the cleaning staff had bottles of shampoo with the hotel crest on their bathroom shelf at home. Everybody’s hair smelled exactly the same, day after day. The only one who was any different was the Woman in the Purple Skirt.

The chilling display of too much interest in another woman’s life is deadpan and scary. A study in voyeurism, the book makes the reader uncomfortable about knowing so much, yet so little, about the narrator’s fixation with the Woman in the Purple Skirt.

In contrast to the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan’s stringent detachment, Fleabag’s unnamed protagonist is so desperately lonely that she hooks up with the first guy who shows interest in her. She breaks the fourth wall to tell the audience of her propensity for these kinds of self-centered, self-destructive antics, while Imamura’s and Lahiri’s character’s motivations are implicit, coiled inside themselves.

These women fill their lives with routines and rituals, some of which are embarrassingly devoid of meaning or circular exercises in theorizing loneliness. “Solitude: it’s become my trade,” Lahiri’s narrator writes. “As it requires a certain discipline, it’s a condition I try to perfect.” Talking of her dead mother, Fleabag says, “With all the love I have for her. I don’t know where to put it now.” The Woman in The Yellow Cardigan wastes her days looking for the familiar face of her estranged sister in a sea of strangers. In the geographies of their lives, in the way they spend their days and live out their obsessions, these women might be markedly different from one another, but loneliness threads through, stitching them together across time, narratives, geographies.

“Nomadland” Swerves from the Manly Road Movie

It is pertinent to note that both Whereabouts and The Woman in the Purple Skirt are works of clear-eyed translation. In an essay for Words Without Borders published in April 2021, Lahiri notes, “The responsibility of translation is as grave and as precarious as that of a surgeon who is trained to transplant organs, or to redirect the blood flow to our hearts, and I wavered at length over the question of who would perform the surgery.” Through these books, both North and Lahiri reveal themselves as quiet seekers of perverse pleasures, working silently into oblivious hours, helping something so grand and pithy in one language find resonance and form in another. In their translations, they render these stories as complex and deeply realized character studies, told with an ambition that would otherwise not be afforded the works in their original languages because of their limited reach.

Lahiri’s Whereabouts was first published in Italian, as Dove Mi Trovo (2018) . She translated it herself, making it the first book published by Knopf to be translated by its own author. Taking the austere, plotless story from Italian and rendering it in English was a task that both petrified and inspired her. And it shows. Lahiri is a meticulous observer of human behavior, good and bad. In the English translation, she loads the most stilted, banal observations with tension. The narrative of Whereabouts unfolds alongside the development of that skill: the narrator, though intensely lonely, is still only beginning to learn how to navigate life alone, to take in experiences and render them powerfully.

Imamura, in The Woman in the Purple Skirt , depicts the life of her narrator as broken, jagged, and abstract, a blend of not-so-youthful obsession with the urge to reach out for someone elusive. North’s translation into English from Imamura’s original Japanese creates a pressing sense that the narrator is grappling with her life. North creates a portrait that shows how certain human traits transcend cultural boundaries. The elements of society, workplace, and general economic downturn are familiar, but there will always be that someone who exists outside these strict peripheries. Towards the end of the novel, the protagonist asks her boss for a loan. He is shocked:

Do you have any idea how many complaints have been made about you by the other staff, saying that even when you do come to work, you often just take off somewhere and disappear? … Usually … you are quiet as a mouse, and now, the first time you open your mouth, it’s to pester me for a loan? What’s the matter with you? Do you have no shame? Someone at your stage in life. Don’t you think you should be a little more restrained in the requests you make of others?

There is poetry to be found in these women’s loneliness, quirk in the slapstick drama, and poignancy in their ways of handling life—but we all know what’s in store for them. No matter how far or wide they cast their net, melancholy will always be a heartbeat away. One extra martini, one more sullen evening alone, one wayward night spent with the wrong guy—anything could send them tipping into a rabbit hole of ceaseless depression. It’s only they who can save themselves. In the face of this truth, what matters is how they keep their bodies and spirits intact, no matter how daunting the obsessions.

As I powerlessly glare at the screen in front of me, a glass of wine waits at the dinner table. It’s only 2 p.m. and I ought to know better. But it’s a Saturday, and I am completely alone. I have no one to talk to, so I give in to the unceasing, animal pleasures of loneliness.

You Might Also Like

Modes of Witness: On “The Singularity” and “The Simple Art of ...

Phantoms of Patriarchy: On Ditlevsen & Bachmann

Fighting Discrimination and Sexual Violence in Women’s Prisons

Lahiri’s Metamorphoses

Tracing Women: Haitian and Black Cuban Women Archivists

On Our Nightstands: July 2024

Loneliness in Literature

Cite this chapter.

- Hamilton B. Gibson 2

133 Accesses

1 Citations

The subject of loneliness in literature is so vast that it is difficult to know how to approach it within the limits of one chapter. It has been a theme treated so often throughout the ages that all that can be done here is to call attention to its use in different periods, and to see how society has regarded loneliness according to the changing Zeitgeist Sometimes writers have concentrated on loneliness associated with old age, as in the Book of Ecclesiastes, which has been mentioned in a previous chapter, and in more modern times loneliness is treated as a problem throughout adult life. Occasionally the loneliness of childhood is dealt with, as in a number of Charles Dickens’s books which refer to his own childhood. Mark Twain’s Huck Finn said, ‘I felt so lonesome I most wished I was dead’ and his remedy for his lonely fits was to fall asleep; Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye experienced it more or less as a permanent problem, and he too regarded death as the final solution for loneliness: ‘I felt so lonesome, all of a sudden, I almost wished I was dead.’ The present book is about loneliness in later life, but it is important to realize that the things that make people lonely are really the same in childhood, mid-adulthood and old age. We are really the same people in our later life, although we have to cope with new problems that come with our age.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Robert Potter, The English Morality Play , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1975.

Google Scholar

G. Cooper and C. Worthan (eds), The Summoning of Everyman , Nederlands, W.A.: Western Australian Press, 1980.

St Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologia , quoted in Ronald Rolheiser, The Restless Heart , London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1979.

Francesco Petrarca, De Vita Solitaria , Leiden: Universitaire Pers Leiden, 1990.