Art for our sake: artists cannot be replaced by machines – study

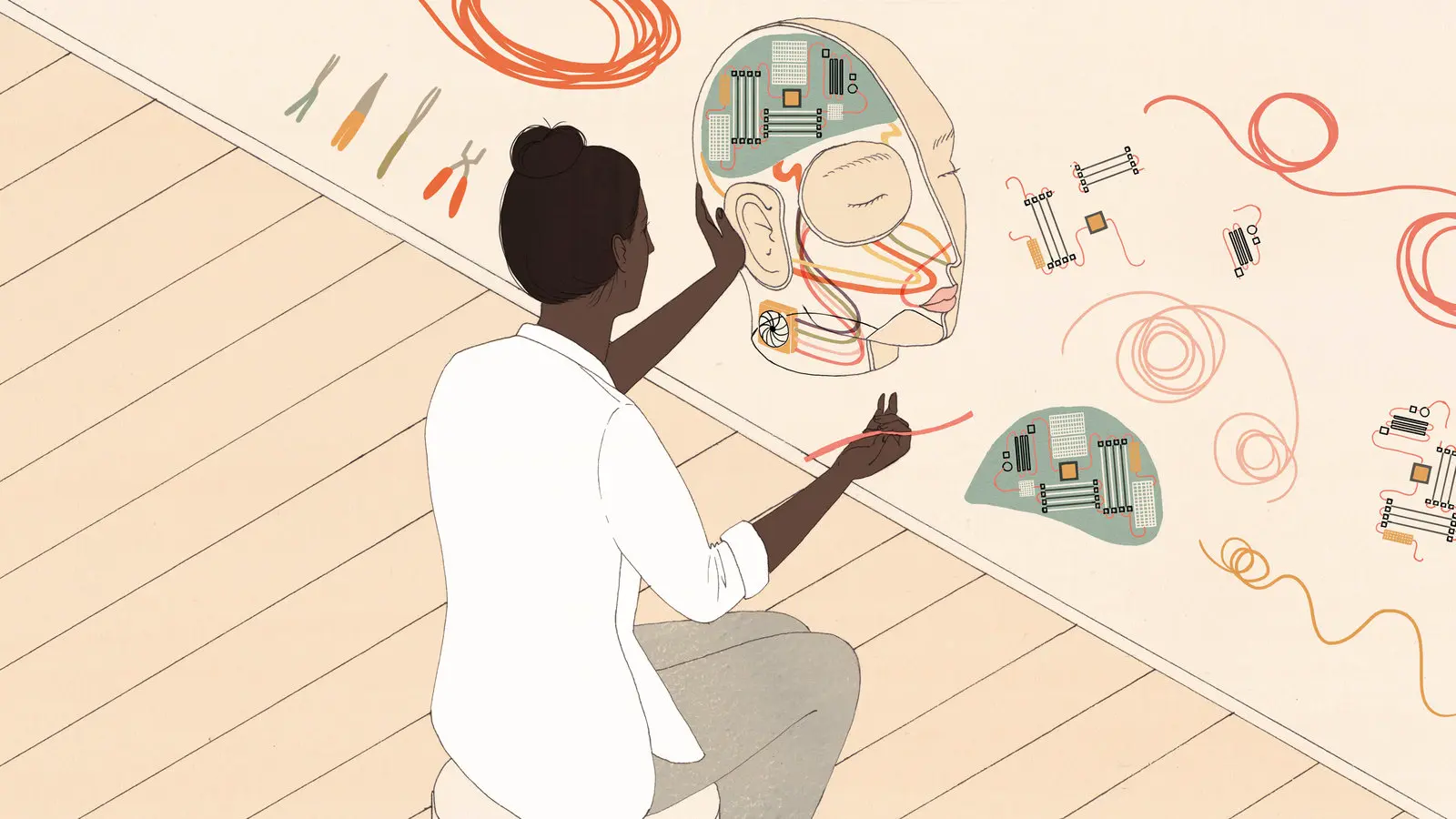

There has been an explosion of interest in ‘creative AI’, but does this mean that artists will be replaced by machines? No, definitely not, says Anne Ploin , Oxford Internet Institute researcher and one of the team behind today’s report on the potential impact of machine learning (ML) on creative work.

The report, ‘ AI and the Arts: How Machine Learning is Changing Artistic Work ’ , was co-authored with OII researchers Professor Rebecca Eynon and Dr Isis Hjorth as well as Professor Michael A. Osborne from Oxford’s Department of Engineering .

Their study took place in 2019, a high point for AI in art. It was also a time of high interest around the role of AI (Artificial Intelligence) in the future of work, and particularly around the idea that automation could transform non-manual professions, with a previous study by Professor Michael A. Osborne and Dr Carl Benedict Frey predicting that some 30% of jobs could, technically, be replaced in an AI revolution by 2030.

Human agency in the creative process is never going away. Parts of the creative process can be automated in interesting ways using AI...but the creative decision-making which results in artworks cannot be replicated by current AI technology

Mx Ploin says it was clear from their research that machine learning was becoming a tool for artists – but will not replace artists. She maintains, ‘The main message is that human agency in the creative process is never going away. Parts of the creative process can be automated in interesting ways using AI (generating many versions of an image, for example), but the creative decision-making which results in artworks cannot be replicated by current AI technology.’

She adds, ‘Artistic creativity is about making choices [what material to use, what to draw/paint/create, what message to carry across to an audience] and develops in the context in which an artist works. Art can be a response to a political context, to an artist’s background, to the world we inhabit. This cannot be replicated using machine learning, which is just a data-driven tool. You cannot – for now – transfer life experience into data.’

She adds, ‘AI models can extrapolate in unexpected ways, draw attention to an entirely unrecognised factor in a certain style of painting [from having been trained on hundreds of artworks]. But machine learning models aren’t autonomous.

Artistic creativity is about making choices ...and develops in the context in which an artist works...the world we inhabit. This cannot be replicated using machine learning, which is just a data-driven tool

‘They aren’t going to create new artistic movements on their own – those are PR stories. The real changes that we’re seeing are around the new skills that artists develop to ‘hack’ technical tools, such as machine learning, to make art on their own terms, and around the importance of curation in an increasingly data-driven world.’

The research paper uses a case study of the use of current machine learning techniques in artistic work, and investigates the scope of AI-enhanced creativity and whether human/algorithm synergies may help unlock human creative potential. In doing so, the report breaks down the uncertainty surrounding the application of AI in the creative arts into three key questions.

- How does using generative algorithms alter the creative processes and embodied experiences of artists?

- How do artists sense and reflect upon the relationship between human and machine creative intelligence?

- What is the nature of human/algorithmic creative complementarity?

According to Mx Ploin, ‘We interviewed 14 experts who work in the creative arts, including media and fine artists whose work centred around generative ML techniques. We also talked to curators and researchers in this field. This allowed us to develop fuller understanding of the implications of AI – ranging from automation to complementarity – in a domain at the heart of human experience: creativity.’

They found a range of responses to the use of machine learning and AI. New activities required by using ML models involved both continuity with previous creative processes and rupture from past practices. There were major changes around the generative process, the evolving ways ML outputs were conceptualised, and artists’ embodied experiences of their practice.

And, says the researcher, there were similarities between the use of machine learning and previous periods in art history, such as the code-based and computer arts of the 1960s and 1970s. But the use of ML models was a “step change” from past tools, according to many artists.

While the machine learning models could help produce ‘surprising variations of existing images’, practitioners felt the artist remained irreplaceable...in making artworks

But, she maintains, while the machine learning models could help produce ‘surprising variations of existing images’, practitioners felt the artist remained irreplaceable in terms of giving images artistic context and intention – that is, in making artworks.

Ultimately, most agreed that despite the increased affordances of ML technologies, the relationship between artists and their media remained essentially unchanged, as artists ultimately work to address human – rather than technical – questions.

Don’t let it put you off going to art school. We need more artists

The report concludes that human/ML complementarity in the arts is a rich and ongoing process, with contemporary artists continuously exploring and expanding technological capabilities to make artworks . Although ML-based processes raise challenges around skills, a common language, resources, and inclusion, what is clear is that the future of ML arts will belong to those with both technical and artistic skills. There is more to come.

But, says Mx Ploin, ‘Don’t let it put you off going to art school. We need more artists.’

Further information

AI and the Arts: How Machine Learning is Changing Artistic Work . Ploin, A., Eynon, R., Hjorth I. & Osborne, M.A. (2022). Report from the Creative Algorithmic Intelligence Research Project. Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, UK. Download the full report .

This report accounts for the findings of the 'Creative Algorithmic Intelligence: Capabilities and Complementarity' project, which ran between 2019 and 2021 as a collaboration between the University of Oxford's Department of Engineering and Oxford Internet Institute.

The report also showcases a range of artworks from contemporary artists who use AI as part of their practice and who participated in our study: Robbie Barrat , Nicolas Boillot , Sofia Crespo , Jake Elwes , Lauren Lee McCarthy , Sarah Meyohas , Anna Ridler , Helena Sarin , and David Young.

DISCOVER MORE

- Support Oxford's research

- Partner with Oxford on research

- Study at Oxford

- Research jobs at Oxford

You can view all news or browse by category

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Art, creativity, and the potential of artificial intelligence.

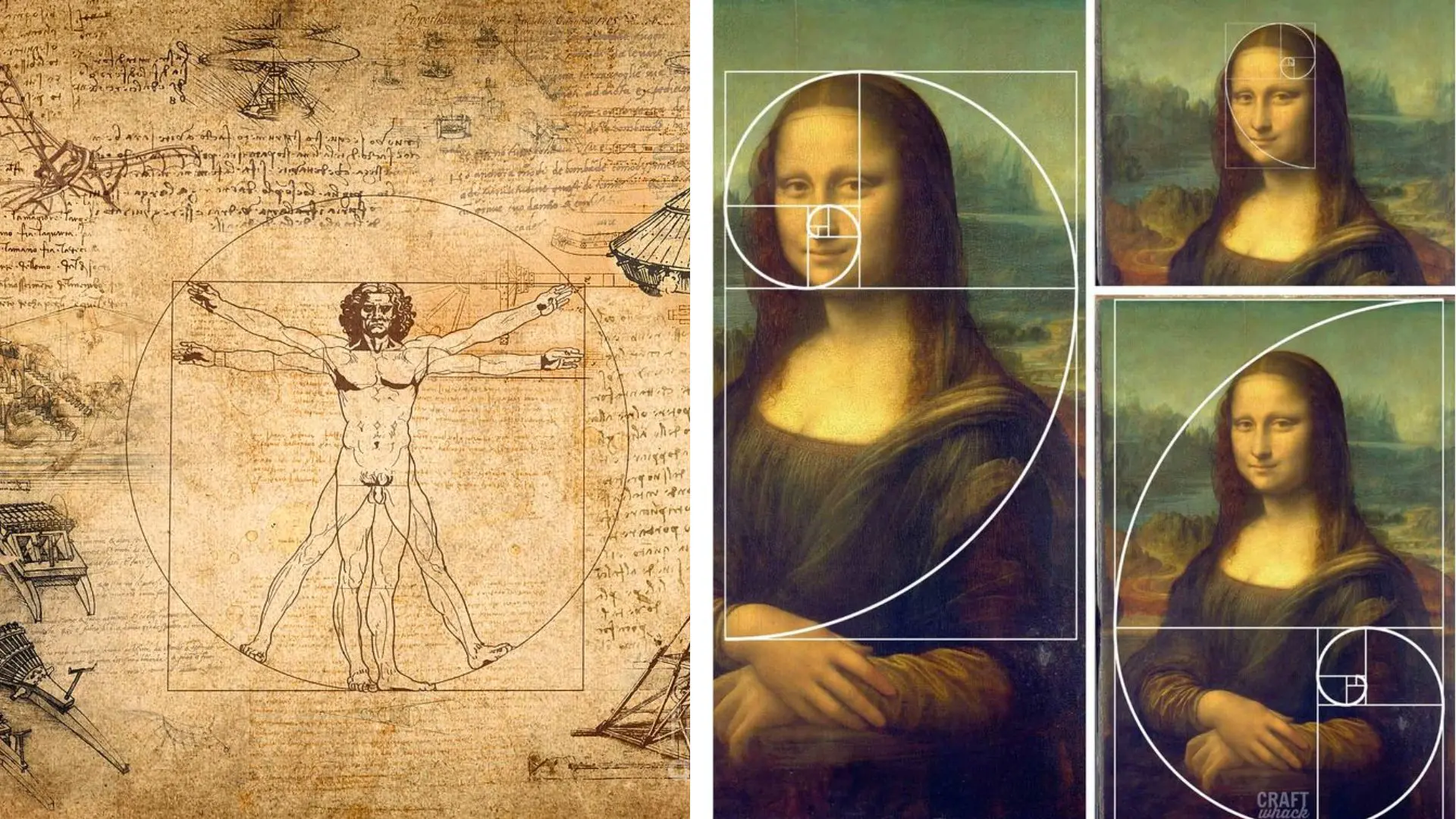

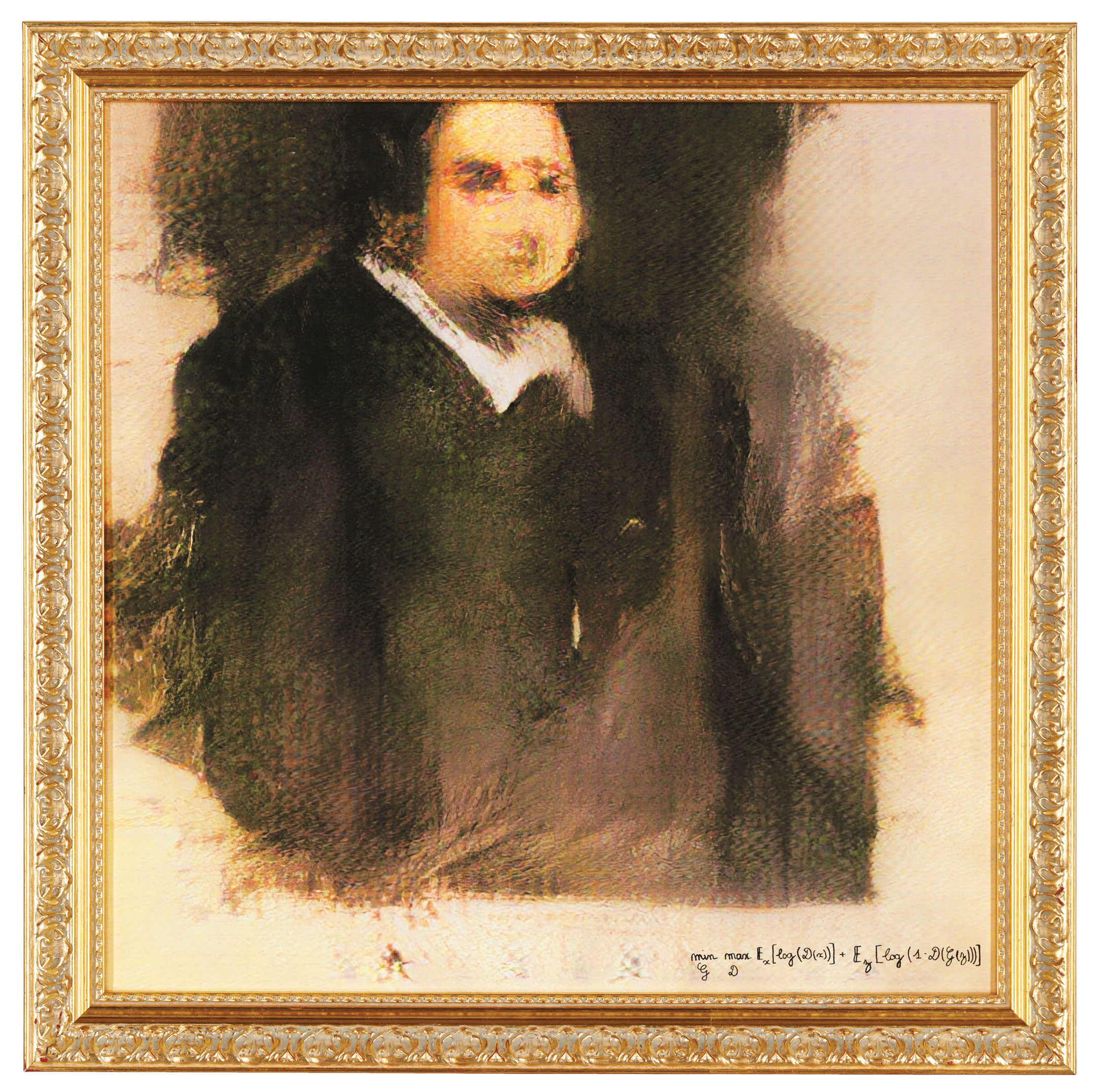

1. AI-Art: GAN, a New Wave of Generative Art

2. pushing the creativity of the machine: creative, not just generative, 3. ai in art and art history, 4. ai art: blurring the lines between the artist and the tool, author contributions, conflicts of interest.

- Agüera y Arcas, Blaise. 2017. Art in the Age of Machine Intelligence. Arts 6: 18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1969. The Work of Art in Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In Illuminations . Edited by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken, pp. 217–51. First published 1936. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berlyne, Daniel E. 1971. Aesthetics and Psychobiology . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts of Meredith Corporation, p. 336. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elgammal, Ahmed, Bingchen Liu, Mohamed Elhoseiny, and Marian Mazzone. 2017. CAN: Creative adversarial networks, generating “art” by learning about styles and deviating from style norms. arXiv , arXiv:1706.07068. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodfellow, Ian, Jean Pouget-Abadie, Mehdi Mirza, Bing Xu, David Warde-Farley, Sherjil Ozair, Aaron Courville, and Yoshua Bengio. 2014. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems . Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 2672–80. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hertzmann, Aaron. 2018. Can Computers Create Art? Arts 7: 18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lewitt, Sol. 1967. Paragraphs on conceptual Art. Artforum 5: 79–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martindale, Colin. 1990. The Clockwork Muse: The Predictability of Artistic Change . New York: Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schneider, Tim, and Naomi Rea. 2018. Has artificial intelligence given us the next great art movement? Experts say slow down, the ‘field is in its infancy. Artnetnews . September 25. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ai-art-comes-to-market-is-it-worth-the-hype-1352011 (accessed on 3 February 2019).

Click here to enlarge figure

Share and Cite

Mazzone, M.; Elgammal, A. Art, Creativity, and the Potential of Artificial Intelligence. Arts 2019 , 8 , 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010026

Mazzone M, Elgammal A. Art, Creativity, and the Potential of Artificial Intelligence. Arts . 2019; 8(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010026

Mazzone, Marian, and Ahmed Elgammal. 2019. "Art, Creativity, and the Potential of Artificial Intelligence" Arts 8, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010026

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Arguments for the Rise of Artificial Intelligence Art: Does AI Art Have Creativity, Motivation, Self-awareness and Emotion?

- Arte 35(3):811-822

- 35(3):811-822

- The University of Edinburgh

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Argyro Ioannidou

- Antonis Lenakakis

- Mingzhu Song

- Zhaoxin Cui

- M. A. W. George

- Ludwig Nagl

- Liyang Wang

- Yonghui Lin

- Alejandra Marinaro

- Jon G McCormack

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

The AI Art Debate: Is it still art if it isn’t expressed by a human (and does it matter)?

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to an ongoing debate about the nature of art and whether AI-generated art can be considered ‘true’ art.

In a traditional sense, people argue that art is a product of human expression, emotion, and experiences. However, others believe that the creative output of AI systems can be considered art in its own right.

In this blog post, we will explore the subject with arguments on both sides of the AI art debate and the implications for the future of artistic expression.

The Argument Against AI Art Being “Art”

Art is Humanity

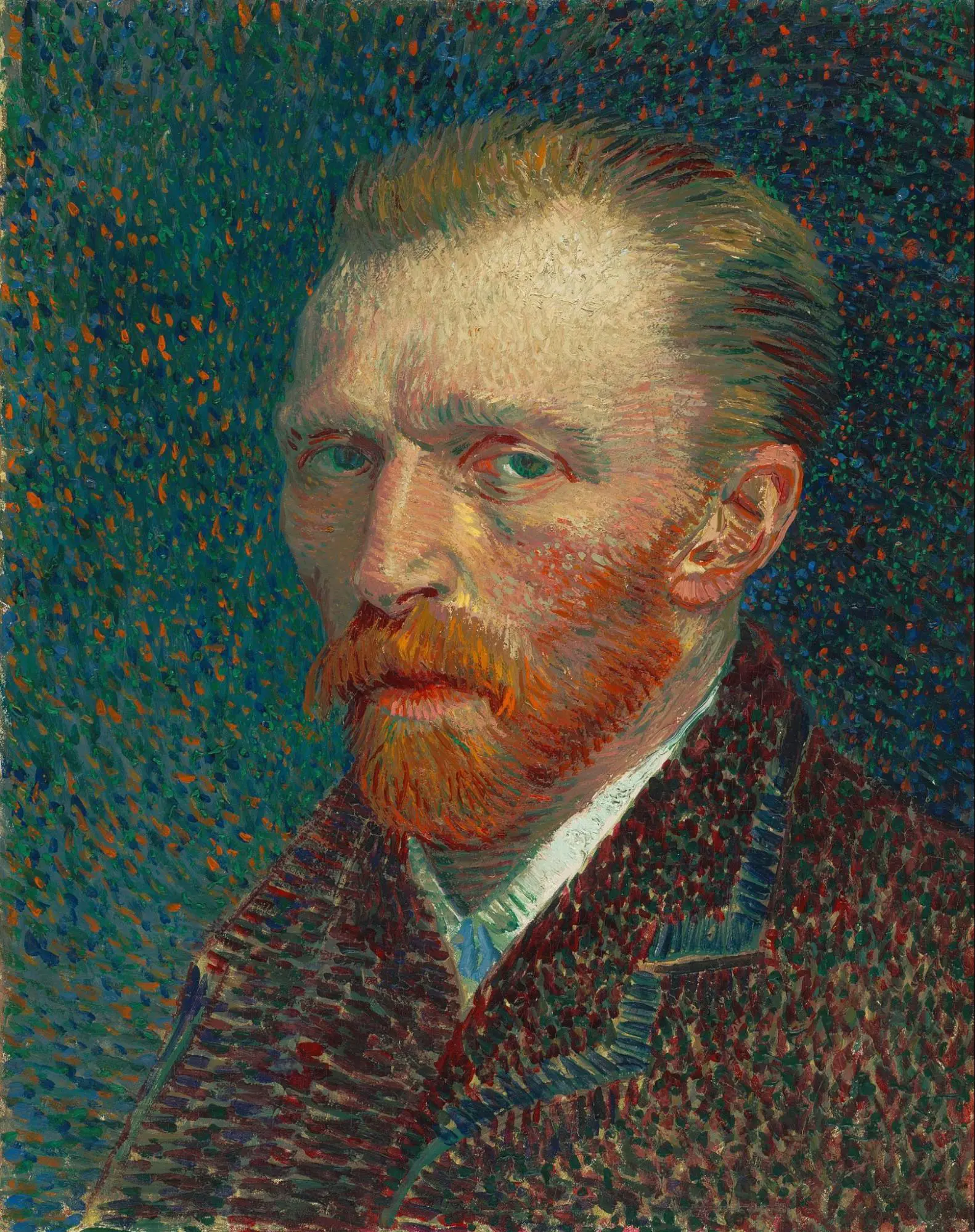

Vincent Willem van Gogh (30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who is among the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In just over a decade he created approximately 2100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of them in the last two years of his life. They include landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and self-portraits, and are characterized by bold, symbolic colours, and dramatic, impulsive, and highly expressive brushwork that contributed to the foundations of modern art. Only one of his paintings was known by name to have been sold during his lifetime. Van Gogh became famous after his suicide at age 37, which followed years of poverty and mental illness.

Critics of AI-generated art argue that art is a product of human expression, experience, and emotion and that machines lack the emotional depth and nuance that human artists bring to their work.

Humans create art as a reflection of their own lives or their perceptions about life. The very act of living as a human, experiencing and expressing as a human, and dying as a human, is unique to humanity itself. The experience of an organic being cannot be dumbed down to mere numbers and data in hopes of mimicking the experiences of human life and emotion.

It can be argued that AI-generated art is devoid of the human element that is essential to the creation of art, or what gives art its true meaning. AI Art Lacks Intentionality

Liberty Leading the People (French: La Liberté guidant le peuple [la libɛʁte ɡidɑ̃ lə pœpl]) is a painting by Eugène Delacroix commemorating the July Revolution of 1830, which toppled King Charles X. A woman of the people with a Phrygian cap personifying the concept of Liberty leads a varied group of people forward over a barricade and the bodies of the fallen, holding aloft the flag of the French Revolution – the tricolour, which again became France's national flag after these events – in one hand and brandishing a bayonetted musket with the other. The figure of Liberty is also viewed as a symbol of France and the French Republic known as Marianne. The painting is sometimes wrongly thought to depict the French Revolution of 1789. Liberty Leading the People is exhibited in the Louvre in Paris.

AI-generated art cannot be considered true art because it lacks “intentionality”. For example, AI could not possibly understand, depict, or recreate the historical significance or context of the painting Liberty Leading the People as shown above.

Intentionality is the fact of being deliberate or purposive. In philosophy, it is the quality of mental states (e.g., thoughts, beliefs, desires, hopes) that consists in their being directed toward some object or state of affairs.

Human artists create art with a specific intention, whether it be to express their emotions, make a political statement, or simply create something beautiful.

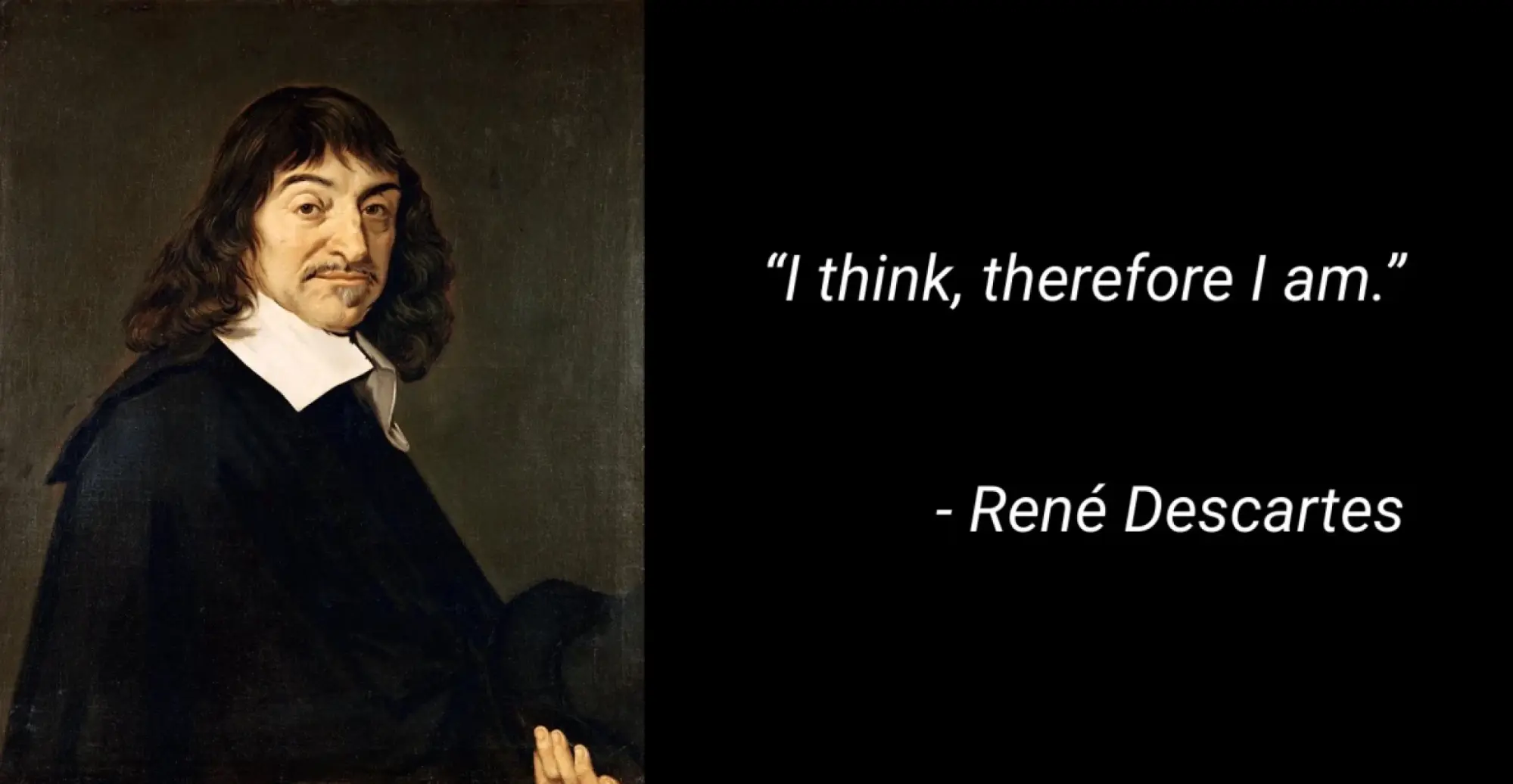

“I think; therefore I am” was the end of the search Descartes conducted for a statement that could not be doubted. He found that he could not doubt that he himself existed, as he was the one doing the doubting in the first place. In Latin (the language in which Descartes wrote), the phrase is “Cogito, ergo sum.”

AI systems, on the other hand, are not capable of intentionality, as they do not possess true “consciousness” or emotions. They cannot be happy or joyous. They do not feel purpose or fulfillment. Conversely, they cannot feel pain, anger, frustration, or sadness.

An AI may mimic human emotions or intelligence/wisdom, but can that truly be considered genuine intelligence when humans program it?

In the traditional sense, the act of an AI mimicking or attempting to instill meaning or intentionality in the “art” it produces is not really “art” as the artificial intelligence program has no emotions, it is not thinking, and there is no intention behind it.

The art that the AI produces is merely copied and pasted from data or numbers and nothing more meaningful lies beyond that.

AI Is Limited By Its Own Bias

AI-generated art is limited by the data it is trained on and is therefore unable to create something truly original on its own.

If you feed it with good information, it can relay the information back to you, but if you feed it with false information, it cannot then turn factually incorrect data into truth. It is unable to distinguish what is truthful or what is ‘good’ on its own - it cannot turn trash into gold.

AI can also be biased because it creates content based on what it thinks its creators like and is limited by what data its creators feed them.

Real art challenges or recontextualizes - it is an act of original thought. Most AI tools can only please. They cannot subvert or invent unless so programmed.

From an ethical perspective, an AI is only as good as the amount of data it can “steal” from human artists and sources, but that is a topic for another time.

AI Art and AI “Everything” - From A Philosophical and Existential Point of View

Existential risk from artificial general intelligence is the hypothesis that substantial progress in artificial general intelligence (AGI) could result in human extinction or an irreversible global catastrophe.

With AI technology advancing at such a rapid rate, people argue even further that there is no point in humans going to school and seeking higher education if robots and AI are going to replace every meaningful task (such as creating art) that humans have traditionally spent their lifetimes doing for thousands of years.

From a purely philosophical and existential point of view - if AI can create all the art there is in the world, then there is no more need for artists, musicians, creators, writers, actors, etc. (the list goes on), removing purpose and fulfillment which is the very meaning of existence for human life.

To stay on topic, however, we will explore this idea in a different blog post.

The Argument for AI Art

The big question remains - is art still considered art if a human didn't create it?

In our journey to answer this question, let us explore why users argue “Yes - AI art is still art”, and why they see no issue in advocating for the usage, development, and advancement of AI-generated or assisted art.

Results Matter, Not Philosophical “Psychobabble”

Those who argue that AI-generated art can be considered “true art” point out that it is the resulting imagery and art created that ultimately matters, and not the means of creation, or its supposed “meaning”.

Once an AI creates a piece of art, the art piece should just be judged “as is”, rather than judged based on any human-perceived idea of meaning (or lack thereof). Just As Good As The “Real” Thing

Proponents of AI art also argue that the creative output of AI systems, when trained on human art, can be aesthetically pleasing, thought-provoking, and emotionally impactful, just like human-generated art.

Art, after all, is subjective, and the “beauty” of an AI-generated art piece is in the eye of the beholder.

Unique In Its Own Right

AI-generated art can be unique, with no two pieces of art ever being the same depending on the prompts and commands you throw at it, making the process and the result a dynamic form of artistic expression in its own right.

By training AI algorithms on large datasets of human-generated art, these algorithms can learn to replicate even the unique styles and techniques of famous and renowned human artists. This is an extension of human creativity, as the AI system is essentially creating art that is inspired by human creativity.

AI Art is (Becoming) Indistinguishable From Human Art

Some even point towards the fact that as technology improves - if we were never explicitly told if a piece of art or tech was created by a human or machine - could we even tell the difference?

If we can’t even tell the difference between what is machine-generated and what is human-generated, blurring the line between “reality” and “virtual”, then what difference does it make in how the art was created?

AI Technology Will Become The “New Normal”

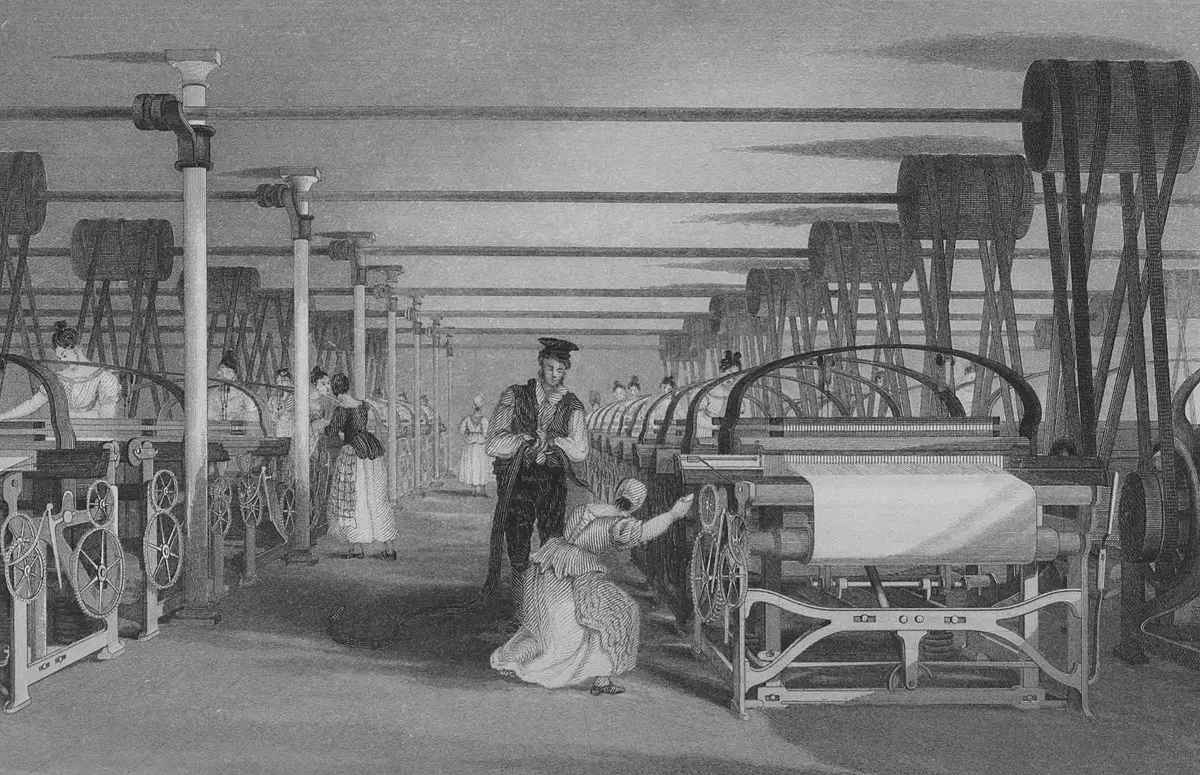

The Industrial Revolution was the transition from creating goods by hand to using machines. Its start and end are widely debated by scholars, but the period generally spanned from about 1760 to 1840.

As technology advances, human life and our way of living will undoubtedly and irrevocably change.

In the world of art specifically, painters and classical artists had to move over and accept new forms of art created by the introduction of human-made technological tools in the past.

The camera invented photography as a new art form and video cameras invented filmography, television, and videography. Musicians who played classical instruments had to give way to electric guitars, electronic music, drum machines, and so on.

At some point in human history, the photographic camera was a completely new technology and threatened the “way of life” of traditional artists everywhere. Now it is accepted as just another way for human beings to capture images and pictures of moments in time and turn them into art.

Just like with the advent of industrial machines, computers, and the internet, the generative AI technology behind AI art and other applications will reach a point where humans will just accept the technology as the new normal baseline (and we are arguably already there). Once a new piece of technology is introduced, it is hard to ignore its use and “put the toothpaste back in the tube”.

AI “Democratizes” Art

Ludo.ai utilizes advanced AI algorithms and machine learning to produce game images, game ideas, video game market research, game elements, and more. Ludo.ai believes in making the video game ideation and production process easier and more efficient for video game developers and studios alike.

In a completely practical sense to human beings (and perhaps to our capitalistic nature), pro-AI art enthusiasts and AI artists alike are more interested in the function AI art and technology serve.

Not everyone is a trained artist or studied art in an art school, and therefore the average person is focused more on the accessibility that AI technology grants rather than whether AI “art” is ethical or was truly created with meaning behind it or not.

AI and AI art can benefit anyone from large corporations, medium to small-sized businesses, indie video game developers, all the way down to the individual solo developer. It promises to make art accessible to everyone and make it much easier and cheaper to create art than ever before, and that is always a positive.

Conclusion: The Implications for the Future of Artistic Expression

The debate around AI art has significant implications for the future of artistic expression.

If we accept AI-generated art as true art, it could lead to a democratization of artistic expression, as anyone with access to AI tools could create art without requiring traditional art skills or training. Additionally, it could provide new opportunities for collaboration between human artists and AI systems.

It is not without negative side effects, however, as fully embracing AI art would lead to a “hyper” commodification and commercialization of art, as art would no longer hold any meaning to humans and would be created solely for profit or to replace human artists to cut costs.

It would be like inventing a food printing machine not to solve world hunger, but to replace the culinary skills of chefs around the world and turn the food industry into a purely money-making scheme rather than farming, preparing, and cooking food for joy, pleasure, culture, and taste.

Embracing AI art would also inevitably lead to a devaluation of traditional art skills and training, as anyone could create “art” with the help of AI tools. Sadly, this was going to happen whether we liked it or not, just like man-made items from a century ago are now either obsolete or all manufactured by machines and rarely by human hands.

On the flip side, if somehow our world leaders gathered together and worked with the creators of AI technology to impose limitations or even bans, AI tech could go down a much weirder and unpredictable, or even dystopian path.

If legal bans were in place, it would protect artists and their livelihoods to continue to be able to make art for a living, but could also create a Prohibition-era world where those who use AI technology wrongfully would be punished or sent to jail.

Ultimately, the debate around AI art is complex and multi-faceted, with valid arguments on both sides. While AI-generated art can be aesthetically pleasing and emotionally impactful, it can be argued that it still lacks the emotional depth and nuance that is unique to human expression.

Whether or not we accept AI-generated art as true art will depend on our definition of art and what we consider to be essential to the (ever-changing) creative process.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

French officer rushes wife, young children out of Salonica as Nazis near

We know about the wars. What about the flowers?

Walking children through a garden of good and evil

If it wasn’t created by a human artist, is it still art.

Illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

Harvard Staff Writer

Writer, animator, architect, musician, and mixed-media artist detail potential value, limit of works produced by AI

The emergence of AI-image generators, such as DALL-E 2 , Discord , Midjourney , and others, has stirred a controversy over whether art generated by artificial intelligence should be considered real art — and whether it could put artists and creators out of work. The Gazette spoke with faculty who are involved in the production of art — a writer, a film animator, an architect, a musician, and a mixed-media artist — to ask them whether they see AI as a threat or a collaborator or a tool to further their own creativity and imagination. The interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

“Most at risk are commercial genres with easily recognizable styles and tropes.”

Photo by Sasha Pedro

Novelist and short-story writer Daphne Kalotay , instructor, Creative Writing & Literature Program, Harvard Extension School

I recently judged a story contest, and reading the shortlist was a clue to the challenges AI might encounter in creating good writing versus great. The best of these human-written stories surprised me with 1) unique ways of viewing the world (personality), 2) linguistic originality, 3) inimitable details that could come only from personal experience. Other stories were written deftly yet lacked these elements of originality and surprise. AI is a superb mimic and quick learner and might easily write strong works in recognizable modes, and with linguistic experimentation if prompted, but — I think — will lack true insight and experience. Most at risk are commercial genres with easily recognizable styles and tropes. Even something like autofiction with its ruminating first-person narrators is easily mimicked — but what will be missing, I’m guessing, is genuine vision from living in a specific physical world.

“That sense of interplay, or the ability to react in the moment, is something that artificial intelligence can’t reproduce.”

Harvard file photo

Saxophonist, percussionist, and composer Yosvany Terry , senior lecturer on music, director of Jazz Bands

When it comes to the performative aspect of music, artificial intelligence is not a concern to me. Music can transmit and represent emotion, and AI cannot do either of those things yet. And especially within jazz and creative music, music is in-the-moment composition, something that happens as musicians are collaborating onstage. That sense of interplay, or the ability to react in the moment, is something that artificial intelligence can’t reproduce because to do that requires being intelligent and having the agency to use your curiosity and your musical vocabulary. Only then, you can be able to react and create music in the moment.

With regards to composition, we know that AI has been used to compose music for film and television for quite a few years. That is a concern because AI is doing the work that musicians used to do. But when you hear those compositions by AI, they lack surprise, emotion, and even silence. I love dramatism in music, and for me, emotion in music is important, and AI is not there yet. As for how music gets to people, this is where we have seen tremendous changes. The many music platforms we have, such as Spotify, YouTube, iTunes, etc., use algorithm-based features, and they make musical recommendations based on what you listen to. We all know that AI is behind it. Musicians would like to see algorithms suggest composers who are less known rather than those who are already popular. The new technology should democratize the field, make sure that people have access to things that are outside the mainstream, and learn to recognize musical traditions that are not only from the Western world.

It’s important to welcome AI with open arms to try to understand what AI can do for us and work with it in creative ways. Any new technology is first seen as a threat to the status quo, like the way radio was received when it first aired. There have always been movements opposing those innovations. I don’t think AI is different, but we must remember that all these innovations are man-made, and as humans we can create and innovate. As a musician, I think we should open our eyes, ears, and arms to work with the new knowledge and innovation that AI can bring.

“AI is acting like a sort of collective unconscious.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Independent animator Ruth Stella Lingford , senior lecturer on Art, Film, and Visual Studies

Often, when I speak to my contemporaries in the animation world, they prefer not to think much about AI. But of course, we need to.

Generally speaking, AI does threaten jobs in the animation industry. I’m told that it is already being used in some large studios. But it will also be a collaborator.

I am told by a knowledgeable friend that it would be possible to train AI on my style and have it work as an assistant in my work. I can see how this would be useful, but, as I actually like the repetitiveness of the animation process, the idea is not very appealing, at least for my own personal work. But it might be a tempting idea in commercial jobs, though I have not explored it yet. In my personal work, the repetition of hand drawing (I draw on a digital tablet) gives me access to a less conscious, intentional side of the creative process, which I think makes the work richer and more nuanced.

Although it is maybe far-fetched to talk about AI as creative or imaginative, the melding of images from different sources, with large elements of the random, closely approximates some aspects of the creative process. AI is acting like a sort of collective unconscious, and I do find some of what it produces very interesting. I don’t suppose that animated films made entirely by AI would be very successful, but used with human guidance throughout the process, they could probably work very well.

I recently attended the Annecy Festival , and many people I spoke to there talked about “riding the shark” — harnessing the power of AI while staying in control. People also predicted the audience’s fatigue with the look of AI. It was noticeable that a high proportion of films shown at this year’s festival were made using recognizably analog techniques — stop-motion, animated painting, etc. — and this seems like a reaction against the dominance of computer-generated imagery in the last years. We do seem to want to see evidence of the human hand. Of course, AI may soon be able to simulate that absolutely seamlessly!

A programmer I spoke to was of the opinion that the panic over the power of AI is hype-manufactured by its makers to disguise its limitations and make it seem sexier. This person saw it going the same way as VR, seeming to offer unlimited potential, but then fizzling out. I would like to think that he’s right, but I can’t quite believe it.

“We should be grateful to be challenged and knocked out of our habits and assumptions!”

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mixed-media artist Matt Saunders ’97, professor and director of undergraduate studies, Department of Art, Film and Visual Studies

To the question of whether AI can be a threat or collaborator, I might respond that every new technology upends conventions and delivers not only new possibilities but a new kind of material intelligence. I am sure many artists will be intrigued by the “agency” of AI and seek ways to grapple or collaborate with it. Many already are. And we should be grateful to be challenged and knocked out of our habits and assumptions! Most of the things that worry me about this fall into the realm of the social and ethical. I hope there are great artists to help us imagine around and work with this new reality.

As to whether it could be creative or comparable, I end up in circular thinking. Art means what we ascribe to it. It can be a provocation, but it is essentially always part of a conversation. Many artists are already using the inventions (and provocations) of AI in works of great substance, but of course the artists are still the ones bringing it into the room. If things change, maybe that will change too.

“If we ask the right questions, AI is going to give us significant answers.”

Sipa via AP Images

Architect and urban planner Moshe Safdie , design critic in architecture, Graduate School of Design

I’ve been following AI since the 1970s, when Marvin Minsky [one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence] and I spent time together. But AI has emerged as the product of an extraordinary computation capacity; algorithm, which is quite different from what Minsky had imagined when he started working on it. For him, AI was the science of making machines be as intelligent as humans, with the capacity for human reasoning.

Right now, it seems to me that AI has an extraordinary capacity to analyze, but I don’t see it yet doing the kinds of things we, architects, do in our head when we design, which involves taking into account a very large number of variables and sorting them out. And yet, as an architect, I think AI can change our lives. If we ask the right questions, AI is going to give us significant answers. For example, I can ask AI, “I have this building that’s sitting on this particular site, and I’d like to optimize the sun, the shadow pattern, and I’d like to position the windows at the place of optimal orientation,” and I think AI could give us a helpful response. We could perfect our designs or improve them based on the response. But I don’t think it’s going to give us the whole answer. For example, if you ask AI to make a garden with hideaways, clearings, and planting arrangements for all the seasons, I think it’ll do that very well. But if you want to have a garden arranged in a way that is magical and pleases you, I’m not sure it can do that.

I’m not frightened of AI at all. I’m intrigued. I think AI will be able to create graphic presentations of extraordinary beauty and interest, but that leads us to the question of what is art. Art has an element that is spiritual, emotional. It is something that happens when you look at Picasso’s “Guernica” and makes you think of the cruelty of humans to humans, or when you look at a Monet piece, and you feel the unity with nature. In terms of art created by AI, I don’t think we can call it art. I don’t see AI yet doing the kind of creative things we do. I can see that it composes a piece of music, but I don’t think it could create Beethoven’s last sonatas on its own. AI can imitate something that’s already been created and regurgitate it in another format, but that is not an original work.

When our firm designed the Jewel Changi Airport in Singapore, our idea was to have retail shops, airport facilities, and an attraction. The idea that this attraction should be a magical garden came from me. I wonder if AI could have come up with the same idea. I don’t think so, but who knows? That would be a very interesting test.

I don’t know if Minsky’s dream of artificial intelligence is attainable because it assumed that AI attains consciousness and independence of thoughts. Therefore, in some ways, artificial intelligence is a misnomer. Maybe I’m underestimating its capacity, but from where I stand as an amateur, because I’m an architect, not a mathematician, it seems to me that intelligence assumes a certain independence and consciousness, which I don’t think AI has right now.

Share this article

More like this.

Will ChatGPT supplant us as writers, thinkers?

What happens when computers take on one of ‘most human’ art forms?

Imagine a world in which AI is in your home, at work, everywhere

You might like.

In novel rooted in family lore, Claire Messud trails three generations of family with Algerian roots, lives shaped by displacement, war, social and political upheaval

Exhibit tracing multicultural exchanges over three centuries finds common threads and plenty of drama, from crown envy to tulip mania

Jamaica Kincaid’s new book presents history of colonialism, identity through plants that helped shape it

John Manning named next provost

His seven-year tenure as Law School dean noted for commitments to academic excellence, innovation, collaboration, and culture of free, open, and respectful discourse

Loving your pup may be a many splendored thing

New research suggests having connection to your dog may lower depression, anxiety

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

MIT Technology Review

- Newsletters

A philosopher argues that an AI can’t be an artist

Creativity is, and always will be, a human endeavor.

- Sean Dorrance Kelly archive page

On March 31, 1913, in the Great Hall of the Musikverein concert house in Vienna, a riot broke out in the middle of a performance of an orchestral song by Alban Berg. Chaos descended. Furniture was broken. Police arrested the concert’s organizer for punching Oscar Straus, a little-remembered composer of operettas. Later, at the trial, Straus quipped about the audience’s frustration. The punch, he insisted, was the most harmonious sound of the entire evening. History has rendered a different verdict: the concert’s conductor, Arnold Schoenberg, has gone down as perhaps the most creative and influential composer of the 20th century.

You may not enjoy Schoenberg’s dissonant music, which rejects conventional tonality to arrange the 12 notes of the scale according to rules that don’t let any predominate. But he changed what humans understand music to be. This is what makes him a genuinely creative and innovative artist. Schoenberg’s techniques are now integrated seamlessly into everything from film scores and Broadway musicals to the jazz solos of Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman.

Creativity is among the most mysterious and impressive achievements of human existence. But what is it?

Creativity is not just novelty. A toddler at the piano may hit a novel sequence of notes, but they’re not, in any meaningful sense, creative. Also, creativity is bounded by history: what counts as creative inspiration in one period or place might be disregarded as ridiculous, stupid, or crazy in another. A community has to accept ideas as good for them to count as creative.

As in Schoenberg’s case, or that of any number of other modern artists, that acceptance need not be universal. It might, indeed, not come for years—sometimes creativity is mistakenly dismissed for generations. But unless an innovation is eventually accepted by some community of practice, it makes little sense to speak of it as creative.

Advances in artificial intelligence have led many to speculate that human beings will soon be replaced by machines in every domain, including that of creativity. Ray Kurzweil, a futurist, predicts that by 2029 we will have produced an AI that can pass for an average educated human being. Nick Bostrom, an Oxford philosopher, is more circumspect. He does not give a date but suggests that philosophers and mathematicians defer work on fundamental questions to “superintelligent” successors, which he defines as having “intellect that greatly exceeds the cognitive performance of humans in virtually all domains of interest.”

Both believe that once human-level intelligence is produced in machines, there will be a burst of progress—what Kurzweil calls the “singularity” and Bostrom an “intelligence explosion”—in which machines will very quickly supersede us by massive measures in every domain. This will occur, they argue, because superhuman achievement is the same as ordinary human achievement except that all the relevant computations are performed much more quickly, in what Bostrom dubs “speed superintelligence.”

So what about the highest level of human achievement—creative innovation? Are our most creative artists and thinkers about to be massively surpassed by machines?

Human creative achievement, because of the way it is socially embedded, will not succumb to advances in artificial intelligence. To say otherwise is to misunderstand both what human beings are and what our creativity amounts to.

This claim is not absolute: it depends on the norms that we allow to govern our culture and our expectations of technology. Human beings have, in the past, attributed great power and genius even to lifeless totems. It is entirely possible that we will come to treat artificially intelligent machines as so vastly superior to us that we will naturally attribute creativity to them. Should that happen, it will not be because machines have outstripped us. It will be because we will have denigrated ourselves.

Human creative achievement, because of the way it is socially embedded, will not succumb to advances in artificial intelligence.

Also, I am primarily talking about machine advances of the sort seen recently with the current deep-learning paradigm, as well as its computational successors. Other paradigms have governed AI research in the past. These have already failed to realize their promise. Still other paradigms may come in the future, but if we speculate that some notional future AI whose features we cannot meaningfully describe will accomplish wondrous things, that is mythmaking, not reasoned argument about the possibilities of technology.

Creative achievement operates differently in different domains. I cannot offer a complete taxonomy of the different kinds of creativity here, so to make the point I will sketch an argument involving three quite different examples: music, games, and mathematics.

Music to my ears

Can we imagine a machine of such superhuman creative ability that it brings about changes in what we understand music to be, as Schoenberg did?

That’s what I claim a machine cannot do. Let’s see why.

Computer music composition systems have existed for quite some time. In 1965, at the age of 17, Kurzweil himself, using a precursor of the pattern recognition systems that characterize deep-learning algorithms today, programmed a computer to compose recognizable music. Variants of this technique are used today. Deep-learning algorithms have been able to take as input a bunch of Bach chorales, for instance, and compose music so characteristic of Bach’s style that it fools even experts into thinking it is original. This is mimicry. It is what an artist does as an apprentice: copy and perfect the style of others instead of working in an authentic, original voice. It is not the kind of musical creativity that we associate with Bach, never mind with Schoenberg’s radical innovation.

So what do we say? Could there be a machine that, like Schoenberg, invents a whole new way of making music? Of course we can imagine, and even make, such a machine. Given an algorithm that modifies its own compositional rules, we could easily produce a machine that makes music as different from what we now consider good music as Schoenberg did then.

But this is where it gets complicated.

We count Schoenberg as a creative innovator not just because he managed to create a new way of composing music but because people could see in it a vision of what the world should be. Schoenberg’s vision involved the spare, clean, efficient minimalism of modernity. His innovation was not just to find a new algorithm for composing music; it was to find a way of thinking about what music is that allows it to speak to what is needed now .

Some might argue that I have raised the bar too high. Am I arguing, they will ask, that a machine needs some mystic, unmeasurable sense of what is socially necessary in order to count as creative? I am not—for two reasons.

First, remember that in proposing a new, mathematical technique for musical composition, Schoenberg changed our understanding of what music is. It is only creativity of this tradition-defying sort that requires some kind of social sensitivity. Had listeners not experienced his technique as capturing the anti-traditionalism at the heart of the radical modernity emerging in early-20th-century Vienna, they might not have heard it as something of aesthetic worth. The point here is that radical creativity is not an “accelerated” version of quotidian creativity. Schoenberg’s achievement is not a faster or better version of the type of creativity demonstrated by Oscar Straus or some other average composer: it’s fundamentally different in kind.

Second, my argument is not that the creator’s responsiveness to social necessity must be conscious for the work to meet the standards of genius. I am arguing instead that we must be able to interpret the work as responding that way . It would be a mistake to interpret a machine’s composition as part of such a vision of the world. The argument for this is simple.

Claims like Kurzweil’s that machines can reach human-level intelligence assume that to have a human mind is just to have a human brain that follows some set of computational algorithms—a view called computationalism. But though algorithms can have moral implications, they are not themselves moral agents. We can’t count the monkey at a typewriter who accidentally types out Othello as a great creative playwright. If there is greatness in the product, it is only an accident. We may be able to see a machine’s product as great, but if we know that the output is merely the result of some arbitrary act or algorithmic formalism, we cannot accept it as the expression of a vision for human good.

For this reason, it seems to me, nothing but another human being can properly be understood as a genuinely creative artist. Perhaps AI will someday proceed beyond its computationalist formalism, but that would require a leap that is unimaginable at the moment. We wouldn’t just be looking for new algorithms or procedures that simulate human activity; we would be looking for new materials that are the basis of being human.

A molecule-for-molecule duplicate of a human being would be human in the relevant way. But we already have a way of producing such a being: it takes about nine months. At the moment, a machine can only do something much less interesting than what a person can do. It can create music in the style of Bach, for instance—perhaps even music that some experts think is better than Bach’s own. But that is only because its music can be judged against a preexisting standard. What a machine cannot do is bring about changes in our standards for judging the quality of music or of understanding what music is or is not.

This is not to deny that creative artists use whatever tools they have at their disposal, and that those tools shape the sort of art they make. The trumpet helped Davis and Coleman realize their creativity. But the trumpet is not, itself, creative. Artificial-intelligence algorithms are more like musical instruments than they are like people. Taryn Southern, a former American Idol contestant, recently released an album where the percussion, melodies, and chords were algorithmically generated, though she wrote the lyrics and repeatedly tweaked the instrumentation algorithm until it delivered the results she wanted. In the early 1990s, David Bowie did it the other way around: he wrote the music and used a Mac app called Verbalizer to pseudorandomly recombine sentences into lyrics. Just like previous tools of the music industry—from recording devices to synthesizers to samplers and loopers—new AI tools work by stimulating and channeling the creative abilities of the human artist (and reflect the limitations of those abilities).

Games without frontiers

Much has been written about the achievements of deep-learning systems that are now the best Go players in the world. AlphaGo and its variants have strong claims to having created a whole new way of playing the game. They have taught human experts that opening moves long thought to be ill-conceived can lead to victory. The program plays in a style that experts describe as strange and alien. “They’re how I imagine games from far in the future,” Shi Yue, a top Go player, said of AlphaGo’s play. The algorithm seems to be genuinely creative.

In some important sense it is. Game-playing, though, is different from composing music or writing a novel: in games there is an objective measure of success. We know we have something to learn from AlphaGo because we see it win.

But that is also what makes Go a “toy domain,” a simplified case that says only limited things about the world.

The most fundamental sort of human creativity changes our understanding of ourselves because it changes our understanding of what we count as good. For the game of Go, by contrast, the nature of goodness is simply not up for grabs: a Go strategy is good if and only if it wins. Human life does not generally have this feature: there is no objective measure of success in the highest realms of achievement. Certainly not in art, literature, music, philosophy, or politics. Nor, for that matter, in the development of new technologies.

In various toy domains, machines may be able to teach us about a certain very constrained form of creativity. But the domain’s rules are pre-formed; the system can succeed only because it learns to play well within these constraints. Human culture and human existence are much more interesting than this. There are norms for how human beings act, of course. But creativity in the genuine sense is the ability to change those norms in some important human domain. Success in toy domains is no indication that creativity of this more fundamental sort is achievable.

It’s a knockout

A skeptic might contend that the argument works only because I’m contrasting games with artistic genius. There are other paradigms of creativity in the scientific and mathematical realm. In these realms, the question isn’t about a vision of the world. It is about the way things actually are.

Might a machine come up with mathematical proofs so far beyond us that we simply have to defer to its creative genius?

Computers have already assisted with notable mathematical achievements. But their contributions haven’t been particularly creative. Take the first major theorem proved using a computer: the four-color theorem, which states that any flat map can be colored with at most four colors in such a way that no two adjacent “countries” end up with the same one (it also applies to countries on the surface of a globe).

Nearly a half-century ago, in 1976, Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken at the University of Illinois published a computer-assisted proof of this theorem. The computer performed billions of calculations, checking thousands of different types of maps—so many that it was (and remains) logistically unfeasible for humans to verify that each possibility accorded with the computer’s view. Since then, computers have assisted in a wide range of new proofs.

But the supercomputer is not doing anything creative by checking a huge number of cases. Instead, it is doing something boring a huge number of times. This seems like almost the opposite of creativity. Furthermore, it is so far from the kind of understanding we normally think a mathematical proof should offer that some experts don’t consider these computer-assisted strategies mathematical proofs at all. As Thomas Tymoczko, a philosopher of mathematics, has argued, if we can’t even verify whether the proof is correct, then all we are really doing is trusting in a potentially error-prone computational process.

Even supposing we do trust the results, however, computer-assisted proofs are something like the analogue of computer-assisted composition. If they give us a worthwhile product, it is mostly because of the contribution of the human being. But some experts have argued that artificial intelligence will be able to achieve more than this. Let us suppose, then, that we have the ultimate: a self-reliant machine that proves new theorems all on its own.

Could a machine like this massively surpass us in mathematical creativity, as Kurzweil and Bostrom argue? Suppose, for instance, that an AI comes up with a resolution to some extremely important and difficult open problem in mathematics.

The capacity for genuine creativity, the kind of creativity that updates our understanding of the nature of being, is at the ground of what it is to be human.

There are two possibilities. The first is that the proof is extremely clever, and when experts in the field go over it they discover that it is correct. In this case, the AI that discovered the proof would be applauded. The machine itself might even be considered to be a creative mathematician. But such a machine would not be evidence of the singularity; it would not so outstrip us in creativity that we couldn’t even understand what it was doing. Even if it had this kind of human-level creativity, it wouldn’t lead inevitably to the realm of the superhuman.

Some mathematicians are like musical virtuosos: they are distinguished by their fluency in an existing idiom. But geniuses like Srinivasa Ramanujan, Emmy Noether, and Alexander Grothendieck arguably reshaped mathematics just as Schoenberg reshaped music. Their achievements were not simply proofs of long-standing hypotheses but new and unexpected forms of reasoning, which took hold not only on the strength of their logic but also on their ability to convince other mathematicians of the significance of their innovations. A notional AI that comes up with a clever proof to a problem that has long befuddled human mathematicians is akin to AlphaGo and its variants: impressive, but nothing like Schoenberg.

That brings us to the other option. Suppose the best and brightest deep-learning algorithm is set loose and after some time says, “I’ve found a proof of a fundamentally new theorem, but it’s too complicated for even your best mathematicians to understand.”

This isn’t actually possible. A proof that not even the best mathematicians can understand doesn’t really count as a proof. Proving something implies that you are proving it to someone . Just as a musician has to persuade her audience to accept her aesthetic concept of what is good music, a mathematician has to persuade other mathematicians that there are good reasons to believe her vision of the truth. To count as a valid proof in mathematics, a claim must be understandable and endorsable by some independent set of experts who are in a good position to understand it. If the experts who should be able to understand the proof can’t, then the community refuses to endorse it as a proof.

For this reason, mathematics is more like music than one might have thought. A machine could not surpass us massively in creativity because either its achievement would be understandable, in which case it would not massively surpass us, or it would not be understandable, in which case we could not count it as making any creative advance at all.

The eye of the beholder

Engineering and applied science are, in a way, somewhere between these examples. There is something like an objective, external measure of success. You can’t “win” at bridge building or medicine the way you can at chess, but one can see whether the bridge falls down or the virus is eliminated. These objective criteria come into play only once the domain is fairly well specified: coming up with strong, lightweight materials, say, or drugs that combat particular diseases. An AI might help in drug discovery by, in effect, doing the same thing as the AI that composed what sounded like a well-executed Bach cantata or came up with a brilliant Go strategy. Like a microscope, telescope, or calculator, such an AI is properly understood as a tool that enables human discovery—not as an autonomous creative agent.

It’s worth thinking about the theory of special relativity here. Albert Einstein is remembered as the “discoverer” of relativity—but not because he was the first to come up with equations that better describe the structure of space and time. George Fitzgerald, Hendrik Lorentz, and Henri Poincaré, among others, had written down those equations before Einstein. He is acclaimed as the theory’s discoverer because he had an original, remarkable, and true understanding of what the equations meant and could convey that understanding to others.

For a machine to do physics that is in any sense comparable to Einstein’s in creativity, it must be able to persuade other physicists of the worth of its ideas at least as well as he did. Which is to say, we would have to be able to accept its proposals as aiming to communicate their own validity to us . Should such a machine ever come into being, as in the parable of Pinocchio, we would have to treat it as we would a human being. That means, among other things, we would have to attribute to it not only intelligence but whatever dignity and moral worth is appropriate to human beings as well. We are a long way off from this scenario, it seems to me, and there is no reason to think the current computationalist paradigm of artificial intelligence—in its deep-learning form or any other—will ever move us closer to it.

Creativity is one of the defining features of human beings. The capacity for genuine creativity, the kind of creativity that updates our understanding of the nature of being, that changes the way we understand what it is to be beautiful or good or true—that capacity is at the ground of what it is to be human. But this kind of creativity depends upon our valuing it, and caring for it, as such. As the writer Brian Christian has pointed out, human beings are starting to act less like beings who value creativity as one of our highest possibilities, and more like machines themselves.

How many people today have jobs that require them to follow a predetermined script for their conversations? How little of what we know as real, authentic, creative, and open-ended human conversation is left in this eviscerated charade? How much is it like, instead, the kind of rule-following that a machine can do? And how many of us, insofar as we allow ourselves to be drawn into these kinds of scripted performances, are eviscerated as well? How much of our day do we allow to be filled with effectively machine-like activities—filling out computerized forms and questionnaires, responding to click-bait that works on our basest, most animal-like impulses, playing games that are designed to optimize our addictive response?

We are in danger of this confusion in some of the deepest domains of human achievement as well. If we allow ourselves to say that machine proofs we cannot understand are genuine “proofs,” for example, ceding social authority to machines, we will be treating the achievements of mathematics as if they required no human understanding at all. We will be taking one of our highest forms of creativity and intelligence and reducing it to a single bit of information: yes or no.

Even if we had that information, it would be of little value to us without some understanding of the reasons underlying it. We must not lose sight of the essential character of reasoning, which is at the foundation of what mathematics is.

So too with art and music and philosophy and literature. If we allow ourselves to slip in this way, to treat machine “creativity” as a substitute for our own, then machines will indeed come to seem incomprehensibly superior to us. But that is because we will have lost track of the fundamental role that creativity plays in being human.

Keep Reading

Most popular.

Supershoes are reshaping distance running

Kenyan runners, like many others, are grappling with the impact of expensive, high-performance shoes.

- Jonathan W. Rosen archive page

Happy birthday, baby! What the future holds for those born today

An intelligent digital agent could be a companion for life—and other predictions for the next 125 years.

- Kara Platoni archive page

This researcher wants to replace your brain, little by little

The US government just hired a researcher who thinks we can beat aging with fresh cloned bodies and brain updates.

- Antonio Regalado archive page

Here’s how people are actually using AI

Something peculiar and slightly unexpected has happened: people have started forming relationships with AI systems.

- Melissa Heikkilä archive page

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from mit technology review.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

If art is how we express our humanity, where does AI fit in?

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

The rapid advance of artificial intelligence has generated a lot of buzz, with some predicting it will lead to an idyllic utopia and others warning it will bring the end of humanity. But speculation about where AI technology is going, while important, can also drown out important conversations about how we should be handling the AI technologies available today.

One such technology is generative AI, which can create content including text, images, audio, and video. Popular generative AIs like the chatbot ChatGPT generate conversational text based on training data taken from the internet.

Today a group of 14 researchers from a number of organizations including MIT published a commentary article in Science that helps set the stage for discussions about generative AI’s immediate impact on creative work and society more broadly. The paper’s MIT-affiliated co-authors include Media Lab postdoc Ziv Epstein SM ’19, PhD ’23; Matt Groh SM ’19, PhD ’23; PhD students Rob Mahari ’17 and Hope Schroeder; and Professor Alex "Sandy" Pentland.

MIT News spoke with Epstein, the lead author of the paper.

Q: Why did you write this paper?

A: Generative AI tools are doing things that even a few years ago we never thought would be possible. This raises a lot of fundamental questions about the creative process and the human’s role in creative production. Are we going to get automated out of jobs? How are we going to preserve the human aspect of creativity with all of these new technologies?

The complexity of black-box AI systems can make it hard for researchers and the broader public to understand what’s happening under the hood, and what the impacts of these tools on society will be. Many discussions about AI anthropomorphize the technology, implicitly suggesting these systems exhibit human-like intent, agency, or self-awareness. Even the term “artificial intelligence” reinforces these beliefs: ChatGPT uses first-person pronouns, and we say AIs “hallucinate.” These agentic roles we give AIs can undermine the credit to creators whose labor underlies the system’s outputs, and can deflect responsibility from the developers and decision makers when the systems cause harm.

We’re trying to build coalitions across academia and beyond to help think about the interdisciplinary connections and research areas necessary to grapple with the immediate dangers to humans coming from the deployment of these tools, such as disinformation, job displacement, and changes to legal structures and culture.

Q: What do you see as the gaps in research around generative AI and art today?

A: The way we talk about AI is broken in many ways. We need to understand how perceptions of the generative process affect attitudes toward outputs and authors, and also design the interfaces and systems in a way that is really transparent about the generative process and avoids some of these misleading interpretations. How do we talk about AI and how do these narratives cut along lines of power? As we outline in the article, there are these themes around AI’s impact that are important to consider: aesthetics and culture; legal aspects of ownership and credit; labor; and the impacts to the media ecosystem. For each of those we highlight the big open questions.

With aesthetics and culture, we’re considering how past art technologies can inform how we think about AI. For example, when photography was invented, some painters said it was “the end of art.” But instead it ended up being its own medium and eventually liberated painting from realism, giving rise to Impressionism and the modern art movement. We’re saying generative AI is a medium with its own affordances. The nature of art will evolve with that. How will artists and creators express their intent and style through this new medium?

Issues around ownership and credit are tricky because we need copyright law that benefits creators, users, and society at large. Today’s copyright laws might not adequately apportion rights to artists when these systems are training on their styles. When it comes to training data, what does it mean to copy? That’s a legal question, but also a technical question. We’re trying to understand if these systems are copying, and when.

For labor economics and creative work, the idea is these generative AI systems can accelerate the creative process in many ways, but they can also remove the ideation process that starts with a blank slate. Sometimes, there’s actually good that comes from starting with a blank page. We don’t know how it’s going to influence creativity, and we need a better understanding of how AI will affect the different stages of the creative process. We need to think carefully about how we use these tools to complement people’s work instead of replacing it.

In terms of generative AI’s effect on the media ecosystem, with the ability to produce synthetic media at scale, the risk of AI-generated misinformation must be considered. We need to safeguard the media ecosystem against the possibility of massive fraud on one hand, and people losing trust in real media on the other.

Q: How do you hope this paper is received — and by whom?

A: The conversation about AI has been very fragmented and frustrating. Because the technologies are moving so fast, it’s been hard to think deeply about these ideas. To ensure the beneficial use of these technologies, we need to build shared language and start to understand where to focus our attention. We’re hoping this paper can be a step in that direction. We’re trying to start a conversation that can help us build a roadmap toward understanding this fast-moving situation.

Artists many times are at the vanguard of new technologies. They’re playing with the technology long before there are commercial applications. They’re exploring how it works, and they’re wrestling with the ethics of it. AI art has been going on for over a decade, and for as long these artists have been grappling with the questions we now face as a society. I think it is critical to uplift the voices of the artists and other creative laborers whose jobs will be impacted by these tools. Art is how we express our humanity. It’s a core human, emotional part of life. In that way we believe it’s at the center of broader questions about AI’s impact on society, and hopefully we can ground that discussion with this.

Share this news article on:

Press mentions, the conversation.

Writing for The Conversation , postdoc Ziv Epstein SM ’19, PhD ’23, graduate student Robert Mahari and Jessica Fjeld of Harvard Law School explore how the use of generative AI will impact creative work. “The ways in which existing laws are interpreted or reformed – and whether generative AI is appropriately treated as the tool it is – will have real consequences for the future of creative expression,” the authors note.

Previous item Next item

Related Links

- Ziv Epstein

- Robert Mahari

- Alex "Sandy" Pentland

- Hope Schroeder

- Human Dynamics group

- School of Architecture and Planning

Related Topics

- Artificial intelligence

- Human-computer interaction

- Technology and society

- Visual arts

- Social justice

Related Articles

MIT CSAIL researchers discuss frontiers of generative AI

On social media platforms, more sharing means less caring about accuracy

A remedy for the spread of false news, more mit news.

Toward a code-breaking quantum computer

Read full story →

Uphill battles: Across the country in 75 days

3 Questions: From the bench to the battlefield

Duane Boning named vice provost for international activities

Q&A: Undergraduate admissions in the wake of the 2023 Supreme Court ruling

Study reveals the benefits and downside of fasting

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- Become a member

Art+Science

Biology + Beyond

One Question

Quanta Abstractions

Science Philanthropy Alliance

Spark of Science

The Porthole

The Reality Issue

The Rebel Issue

Women in Science & Engineering

- Anthropology

- Communication

- Environment

- Microbiology

- Neuroscience

- Paleontology

Already a member? Log in

Is ai art really art.

What it will mean to be moved by an AI’s mindless creativity.

- By Ed Simon

- November 9, 2022

M aureen F. McHugh’s short story collection After the Apocalypse was merely prescient when published in 2011, but it appears positively prophetic a decade later with its narratives about respiratory virus pandemics, frayed social connections, and increased political violence. Few of her tales, however, are as haunting as “The Kingdom of the Blind,” which will perhaps prove to be the most visionary of McHugh’s stories. “The Kingdom of the Blind” takes as its subject artificial intelligence, grappling with the possibility that any consciousness which arises from soldering board and circuitry may be so alien that it’s scarcely recognizable to us as a consciousness in the first place. The emergent process of consciousness as it develops in this AI is inscrutable and totally different from anything which resembles human thinking, posing a difficulty for the computer scientists who attempt to communicate with it.

In sparse, elegant, and beautiful prose, McHugh’s story describes how a massive interconnected computer program evolves a quality that could be described as “consciousness,” and yet how to describe the thought which animates this being is impossible. The main character Sydney reflects that as concerns the AI, “She didn’t know what it was. Didn’t know how to think about it. It was as opaque as a stone.” Readers and viewers of science fiction have long been familiar with artificial intelligences, but even at their most foreign—HAL-9000 in Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or Lt. Cmdr. Data in Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek: The Next Generation— there is still something recognizably human in them. McHugh’s story poses a rather more alarming—and perhaps more realistic—scenario. Maybe we’d try to talk to an artificial intelligence, and it wouldn’t even be able to hear us. How then, are we to interpret such things, when those computers try to speak to us?

We’re at the cusp of an AI revolution

This past summer, the research laboratory OpenAI released an open-source version of a program, rather cheekily christened “DALL-E 2” as a portmanteau of the Spanish surrealist painter and the beloved Pixar robot, that was able to rapidly create stunningly proficient artwork. It resulted in a surge in popularity on social media. On Twitter and Facebook, people shared the results of prompts which they fed to DALL-E, and like Sydney in McHugh’s story, the disquieting and uncanny art which was produced forced many to consider certain questions about the nature of consciousness and creation. When I typed in the prompt “Robot Shakespeare,” I was presented after a few minutes with a picture clearly modeled on the frontispiece engraving of the playwright from the first edition of his folio printed in 1623, except rather wittily the creases in his jacket appear almost as if electric circuitry, the face an android’s mask. When given the combination of words “monkey typewriter,” in reference to the old conceit which asks how long it would take for a bevy of assorted simians randomly banging on keyboards to accidently reproduce all of Shakespeare’s corpus, DALL-E 2 presents me with an electric typewriter with a stuffed ape toy emerging from the platter of the device.

DALL-E 2 is obviously not as sophisticated as the emergent consciousness from “The Kingdom of the Blind,” yet its eerie alterity is reminiscent; the vague sense that some of these occasionally strangely beautiful and in other instances hilariously misguided images are being produced by a mind, of some sort at least. Less popular than the artistic images produced by DALL-E 2 are the in some sense more disquieting examples of spontaneously generated text, the output of the computers that produce literature. For example, consider the following prose-poem:

“You must listen to the song of the void,” they whisper

“You must look into the abyss of nothingness,” they whisper

“You must write the words that will bring clarity to the chaos,” they whisper

“You must speak to the unspoken, to the inarticulate, to the unsaid,” they whisper.