13 Different Types of Hypothesis

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

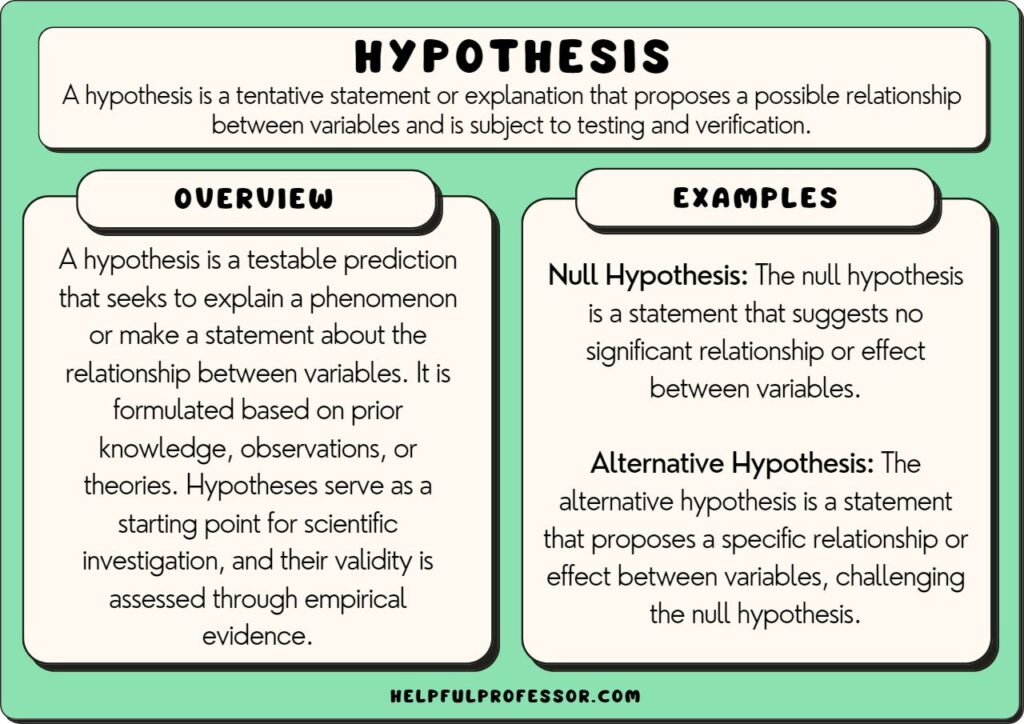

There are 13 different types of hypothesis. These include simple, complex, null, alternative, composite, directional, non-directional, logical, empirical, statistical, associative, exact, and inexact.

A hypothesis can be categorized into one or more of these types. However, some are mutually exclusive and opposites. Simple and complex hypotheses are mutually exclusive, as are direction and non-direction, and null and alternative hypotheses.

Below I explain each hypothesis in simple terms for absolute beginners. These definitions may be too simple for some, but they’re designed to be clear introductions to the terms to help people wrap their heads around the concepts early on in their education about research methods .

Types of Hypothesis

Before you Proceed: Dependent vs Independent Variables

A research study and its hypotheses generally examine the relationships between independent and dependent variables – so you need to know these two concepts:

- The independent variable is the variable that is causing a change.

- The dependent variable is the variable the is affected by the change. This is the variable being tested.

Read my full article on dependent vs independent variables for more examples.

Example: Eating carrots (independent variable) improves eyesight (dependent variable).

1. Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a hypothesis that predicts a correlation between two test variables: an independent and a dependent variable.

This is the easiest and most straightforward type of hypothesis. You simply need to state an expected correlation between the dependant variable and the independent variable.

You do not need to predict causation (see: directional hypothesis). All you would need to do is prove that the two variables are linked.

Simple Hypothesis Examples

2. complex hypothesis.

A complex hypothesis is a hypothesis that contains multiple variables, making the hypothesis more specific but also harder to prove.

You can have multiple independent and dependant variables in this hypothesis.

Complex Hypothesis Example

In the above example, we have multiple independent and dependent variables:

- Independent variables: Age and weight.

- Dependent variables: diabetes and heart disease.

Because there are multiple variables, this study is a lot more complex than a simple hypothesis. It quickly gets much more difficult to prove these hypotheses. This is why undergraduate and first-time researchers are usually encouraged to use simple hypotheses.

3. Null Hypothesis

A null hypothesis will predict that there will be no significant relationship between the two test variables.

For example, you can say that “The study will show that there is no correlation between marriage and happiness.”

A good way to think about a null hypothesis is to think of it in the same way as “innocent until proven guilty”[1]. Unless you can come up with evidence otherwise, your null hypothesis will stand.

A null hypothesis may also highlight that a correlation will be inconclusive . This means that you can predict that the study will not be able to confirm your results one way or the other. For example, you can say “It is predicted that the study will be unable to confirm a correlation between the two variables due to foreseeable interference by a third variable .”

Beware that an inconclusive null hypothesis may be questioned by your teacher. Why would you conduct a test that you predict will not provide a clear result? Perhaps you should take a closer look at your methodology and re-examine it. Nevertheless, inconclusive null hypotheses can sometimes have merit.

Null Hypothesis Examples

4. alternative hypothesis.

An alternative hypothesis is a hypothesis that is anything other than the null hypothesis. It will disprove the null hypothesis.

We use the symbol H A or H 1 to denote an alternative hypothesis.

The null and alternative hypotheses are usually used together. We will say the null hypothesis is the case where a relationship between two variables is non-existent. The alternative hypothesis is the case where there is a relationship between those two variables.

The following statement is always true: H 0 ≠ H A .

Let’s take the example of the hypothesis: “Does eating oatmeal before an exam impact test scores?”

We can have two hypotheses here:

- Null hypothesis (H 0 ): “Eating oatmeal before an exam does not impact test scores.”

- Alternative hypothesis (H A ): “Eating oatmeal before an exam does impact test scores.”

For the alternative hypothesis to be true, all we have to do is disprove the null hypothesis for the alternative hypothesis to be true. We do not need an exact prediction of how much oatmeal will impact the test scores or even if the impact is positive or negative. So long as the null hypothesis is proven to be false, then the alternative hypothesis is proven to be true.

5. Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a hypothesis that does not predict the exact parameters, distribution, or range of the dependent variable.

Often, we would predict an exact outcome. For example: “23 year old men are on average 189cm tall.” Here, we are giving an exact parameter. So, the hypothesis is not composite.

But, often, we cannot exactly hypothesize something. We assume that something will happen, but we’re not exactly sure what. In these cases, we might say: “23 year old men are not on average 189cm tall.”

We haven’t set a distribution range or exact parameters of the average height of 23 year old men. So, we’ve introduced a composite hypothesis as opposed to an exact hypothesis.

Generally, an alternative hypothesis (discussed above) is composite because it is defined as anything except the null hypothesis. This ‘anything except’ does not define parameters or distribution, and therefore it’s an example of a composite hypothesis.

6. Directional Hypothesis

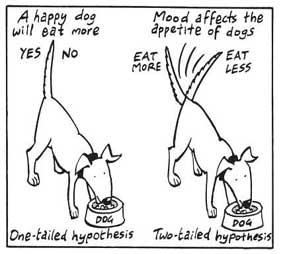

A directional hypothesis makes a prediction about the positivity or negativity of the effect of an intervention prior to the test being conducted.

Instead of being agnostic about whether the effect will be positive or negative, it nominates the effect’s directionality.

We often call this a one-tailed hypothesis (in contrast to a two-tailed or non-directional hypothesis) because, looking at a distribution graph, we’re hypothesizing that the results will lean toward one particular tail on the graph – either the positive or negative.

Directional Hypothesis Examples

7. non-directional hypothesis.

A non-directional hypothesis does not specify the predicted direction (e.g. positivity or negativity) of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

These hypotheses predict an effect, but stop short of saying what that effect will be.

A non-directional hypothesis is similar to composite and alternative hypotheses. All three types of hypothesis tend to make predictions without defining a direction. In a composite hypothesis, a specific prediction is not made (although a general direction may be indicated, so the overlap is not complete). For an alternative hypothesis, you often predict that the even will be anything but the null hypothesis, which means it could be more or less than H 0 (or in other words, non-directional).

Let’s turn the above directional hypotheses into non-directional hypotheses.

Non-Directional Hypothesis Examples

8. logical hypothesis.

A logical hypothesis is a hypothesis that cannot be tested, but has some logical basis underpinning our assumptions.

These are most commonly used in philosophy because philosophical questions are often untestable and therefore we must rely on our logic to formulate logical theories.

Usually, we would want to turn a logical hypothesis into an empirical one through testing if we got the chance. Unfortunately, we don’t always have this opportunity because the test is too complex, expensive, or simply unrealistic.

Here are some examples:

- Before the 1980s, it was hypothesized that the Titanic came to its resting place at 41° N and 49° W, based on the time the ship sank and the ship’s presumed path across the Atlantic Ocean. However, due to the depth of the ocean, it was impossible to test. Thus, the hypothesis was simply a logical hypothesis.

- Dinosaurs closely related to Aligators probably had green scales because Aligators have green scales. However, as they are all extinct, we can only rely on logic and not empirical data.

9. Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is the opposite of a logical hypothesis. It is a hypothesis that is currently being tested using scientific analysis. We can also call this a ‘working hypothesis’.

We can to separate research into two types: theoretical and empirical. Theoretical research relies on logic and thought experiments. Empirical research relies on tests that can be verified by observation and measurement.

So, an empirical hypothesis is a hypothesis that can and will be tested.

- Raising the wage of restaurant servers increases staff retention.

- Adding 1 lb of corn per day to cows’ diets decreases their lifespan.

- Mushrooms grow faster at 22 degrees Celsius than 27 degrees Celsius.

Each of the above hypotheses can be tested, making them empirical rather than just logical (aka theoretical).

10. Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis utilizes representative statistical models to draw conclusions about broader populations.

It requires the use of datasets or carefully selected representative samples so that statistical inference can be drawn across a larger dataset.

This type of research is necessary when it is impossible to assess every single possible case. Imagine, for example, if you wanted to determine if men are taller than women. You would be unable to measure the height of every man and woman on the planet. But, by conducting sufficient random samples, you would be able to predict with high probability that the results of your study would remain stable across the whole population.

You would be right in guessing that almost all quantitative research studies conducted in academic settings today involve statistical hypotheses.

Statistical Hypothesis Examples

- Human Sex Ratio. The most famous statistical hypothesis example is that of John Arbuthnot’s sex at birth case study in 1710. Arbuthnot used birth data to determine with high statistical probability that there are more male births than female births. He called this divine providence, and to this day, his findings remain true: more men are born than women.

- Lady Testing Tea. A 1935 study by Ronald Fisher involved testing a woman who believed she could tell whether milk was added before or after water to a cup of tea. Fisher gave her 4 cups in which one randomly had milk placed before the tea. He repeated the test 8 times. The lady was correct each time. Fisher found that she had a 1 in 70 chance of getting all 8 test correct, which is a statistically significant result.

11. Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis predicts that two variables are linked but does not explore whether one variable directly impacts upon the other variable.

We commonly refer to this as “ correlation does not mean causation ”. Just because there are a lot of sick people in a hospital, it doesn’t mean that the hospital made the people sick. There is something going on there that’s causing the issue (sick people are flocking to the hospital).

So, in an associative hypothesis, you note correlation between an independent and dependent variable but do not make a prediction about how the two interact. You stop short of saying one thing causes another thing.

Associative Hypothesis Examples

- Sick people in hospital. You could conduct a study hypothesizing that hospitals have more sick people in them than other institutions in society. However, you don’t hypothesize that the hospitals caused the sickness.

- Lice make you healthy. In the Middle Ages, it was observed that sick people didn’t tend to have lice in their hair. The inaccurate conclusion was that lice was not only a sign of health, but that they made people healthy. In reality, there was an association here, but not causation. The fact was that lice were sensitive to body temperature and fled bodies that had fevers.

12. Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis predicts that two variables are not only associated, but that changes in one variable will cause changes in another.

A causal hypothesis is harder to prove than an associative hypothesis because the cause needs to be definitively proven. This will often require repeating tests in controlled environments with the researchers making manipulations to the independent variable, or the use of control groups and placebo effects .

If we were to take the above example of lice in the hair of sick people, researchers would have to put lice in sick people’s hair and see if it made those people healthier. Researchers would likely observe that the lice would flee the hair, but the sickness would remain, leading to a finding of association but not causation.

Causal Hypothesis Examples

13. exact vs. inexact hypothesis.

For brevity’s sake, I have paired these two hypotheses into the one point. The reality is that we’ve already seen both of these types of hypotheses at play already.

An exact hypothesis (also known as a point hypothesis) specifies a specific prediction whereas an inexact hypothesis assumes a range of possible values without giving an exact outcome. As Helwig [2] argues:

“An “exact” hypothesis specifies the exact value(s) of the parameter(s) of interest, whereas an “inexact” hypothesis specifies a range of possible values for the parameter(s) of interest.”

Generally, a null hypothesis is an exact hypothesis whereas alternative, composite, directional, and non-directional hypotheses are all inexact.

See Next: 15 Hypothesis Examples

This is introductory information that is basic and indeed quite simplified for absolute beginners. It’s worth doing further independent research to get deeper knowledge of research methods and how to conduct an effective research study. And if you’re in education studies, don’t miss out on my list of the best education studies dissertation ideas .

[1] https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/91/6/571.abstract

[2] http://users.stat.umn.edu/~helwig/notes/SignificanceTesting.pdf

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

2 thoughts on “13 Different Types of Hypothesis”

Wow! This introductionary materials are very helpful. I teach the begginers in research for the first time in my career. The given tips and materials are very helpful. Chris, thank you so much! Excellent materials!

You’re more than welcome! If you want a pdf version of this article to provide for your students to use as a weekly reading on in-class discussion prompt for seminars, just drop me an email in the Contact form and I’ll get one sent out to you.

When I’ve taught this seminar, I’ve put my students into groups, cut these definitions into strips, and handed them out to the groups. Then I get them to try to come up with hypotheses that fit into each ‘type’. You can either just rotate hypothesis types so they get a chance at creating a hypothesis of each type, or get them to “teach” their hypothesis type and examples to the class at the end of the seminar.

Cheers, Chris

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

- Maths Notes Class 12

- NCERT Solutions Class 12

- RD Sharma Solutions Class 12

- Maths Formulas Class 12

- Maths Previous Year Paper Class 12

- Class 12 Syllabus

- Class 12 Revision Notes

- Physics Notes Class 12

- Chemistry Notes Class 12

- Biology Notes Class 12

Hypothesis | Definition, Meaning and Examples

Hypothesis is a hypothesis is fundamental concept in the world of research and statistics. It is a testable statement that explains what is happening or observed. It proposes the relation between the various participating variables.

Hypothesis is also called Theory, Thesis, Guess, Assumption, or Suggestion . Hypothesis creates a structure that guides the search for knowledge.

In this article, we will learn what hypothesis is, its characteristics, types, and examples. We will also learn how hypothesis helps in scientific research.

Table of Content

What is Hypothesis?

Characteristics of hypothesis, sources of hypothesis, types of hypothesis, functions of hypothesis, how hypothesis help in scientific research.

Hypothesis is a suggested idea or an educated guess or a proposed explanation made based on limited evidence, serving as a starting point for further study. They are meant to lead to more investigation.

It's mainly a smart guess or suggested answer to a problem that can be checked through study and trial. In science work, we make guesses called hypotheses to try and figure out what will happen in tests or watching. These are not sure things but rather ideas that can be proved or disproved based on real-life proofs. A good theory is clear and can be tested and found wrong if the proof doesn't support it.

Hypothesis Meaning

A hypothesis is a proposed statement that is testable and is given for something that happens or observed.

- It is made using what we already know and have seen, and it's the basis for scientific research.

- A clear guess tells us what we think will happen in an experiment or study.

- It's a testable clue that can be proven true or wrong with real-life facts and checking it out carefully.

- It usually looks like a "if-then" rule, showing the expected cause and effect relationship between what's being studied.

Here are some key characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable: An idea (hypothesis) should be made so it can be tested and proven true through doing experiments or watching. It should show a clear connection between things.

- Specific: It needs to be easy and on target, talking about a certain part or connection between things in a study.

- Falsifiable: A good guess should be able to show it's wrong. This means there must be a chance for proof or seeing something that goes against the guess.

- Logical and Rational: It should be based on things we know now or have seen, giving a reasonable reason that fits with what we already know.

- Predictive: A guess often tells what to expect from an experiment or observation. It gives a guide for what someone might see if the guess is right.

- Concise: It should be short and clear, showing the suggested link or explanation simply without extra confusion.

- Grounded in Research: A guess is usually made from before studies, ideas or watching things. It comes from a deep understanding of what is already known in that area.

- Flexible: A guess helps in the research but it needs to change or fix when new information comes up.

- Relevant: It should be related to the question or problem being studied, helping to direct what the research is about.

- Empirical: Hypotheses come from observations and can be tested using methods based on real-world experiences.

Hypotheses can come from different places based on what you're studying and the kind of research. Here are some common sources from which hypotheses may originate:

- Existing Theories: Often, guesses come from well-known science ideas. These ideas may show connections between things or occurrences that scientists can look into more.

- Observation and Experience: Watching something happen or having personal experiences can lead to guesses. We notice odd things or repeat events in everyday life and experiments. This can make us think of guesses called hypotheses.

- Previous Research: Using old studies or discoveries can help come up with new ideas. Scientists might try to expand or question current findings, making guesses that further study old results.

- Literature Review: Looking at books and research in a subject can help make guesses. Noticing missing parts or mismatches in previous studies might make researchers think up guesses to deal with these spots.

- Problem Statement or Research Question: Often, ideas come from questions or problems in the study. Making clear what needs to be looked into can help create ideas that tackle certain parts of the issue.

- Analogies or Comparisons: Making comparisons between similar things or finding connections from related areas can lead to theories. Understanding from other fields could create new guesses in a different situation.

- Hunches and Speculation: Sometimes, scientists might get a gut feeling or make guesses that help create ideas to test. Though these may not have proof at first, they can be a beginning for looking deeper.

- Technology and Innovations: New technology or tools might make guesses by letting us look at things that were hard to study before.

- Personal Interest and Curiosity: People's curiosity and personal interests in a topic can help create guesses. Scientists could make guesses based on their own likes or love for a subject.

Here are some common types of hypotheses:

Simple Hypothesis

Complex hypothesis, directional hypothesis.

- Non-directional Hypothesis

Null Hypothesis (H0)

Alternative hypothesis (h1 or ha), statistical hypothesis, research hypothesis, associative hypothesis, causal hypothesis.

Simple Hypothesis guesses a connection between two things. It says that there is a connection or difference between variables, but it doesn't tell us which way the relationship goes. Example: Studying more can help you do better on tests. Getting more sun makes people have higher amounts of vitamin D.

Complex Hypothesis tells us what will happen when more than two things are connected. It looks at how different things interact and may be linked together. Example: How rich you are, how easy it is to get education and healthcare greatly affects the number of years people live. A new medicine's success relies on the amount used, how old a person is who takes it and their genes.

Directional Hypothesis says how one thing is related to another. For example, it guesses that one thing will help or hurt another thing. Example: Drinking more sweet drinks is linked to a higher body weight score. Too much stress makes people less productive at work.

Non-Directional Hypothesis

Non-Directional Hypothesis are the one that don't say how the relationship between things will be. They just say that there is a connection, without telling which way it goes. Example: Drinking caffeine can affect how well you sleep. People often like different kinds of music based on their gender.

Null hypothesis is a statement that says there's no connection or difference between different things. It implies that any seen impacts are because of luck or random changes in the information. Example: The average test scores of Group A and Group B are not much different. There is no connection between using a certain fertilizer and how much it helps crops grow.

Alternative Hypothesis is different from the null hypothesis and shows that there's a big connection or gap between variables. Scientists want to say no to the null hypothesis and choose the alternative one. Example: Patients on Diet A have much different cholesterol levels than those following Diet B. Exposure to a certain type of light can change how plants grow compared to normal sunlight.

Statistical Hypothesis are used in math testing and include making ideas about what groups or bits of them look like. You aim to get information or test certain things using these top-level, common words only. Example: The average smarts score of kids in a certain school area is 100. The usual time it takes to finish a job using Method A is the same as with Method B.

Research Hypothesis comes from the research question and tells what link is expected between things or factors. It leads the study and chooses where to look more closely. Example: Having more kids go to early learning classes helps them do better in school when they get older. Using specific ways of talking affects how much customers get involved in marketing activities.

Associative Hypothesis guesses that there is a link or connection between things without really saying it caused them. It means that when one thing changes, it is connected to another thing changing. Example: Regular exercise helps to lower the chances of heart disease. Going to school more can help people make more money.

Causal Hypothesis are different from other ideas because they say that one thing causes another. This means there's a cause and effect relationship between variables involved in the situation. They say that when one thing changes, it directly makes another thing change. Example: Playing violent video games makes teens more likely to act aggressively. Less clean air directly impacts breathing health in city populations.

Hypotheses have many important jobs in the process of scientific research. Here are the key functions of hypotheses:

- Guiding Research: Hypotheses give a clear and exact way for research. They act like guides, showing the predicted connections or results that scientists want to study.

- Formulating Research Questions: Research questions often create guesses. They assist in changing big questions into particular, checkable things. They guide what the study should be focused on.

- Setting Clear Objectives: Hypotheses set the goals of a study by saying what connections between variables should be found. They set the targets that scientists try to reach with their studies.

- Testing Predictions: Theories guess what will happen in experiments or observations. By doing tests in a planned way, scientists can check if what they see matches the guesses made by their ideas.

- Providing Structure: Theories give structure to the study process by arranging thoughts and ideas. They aid scientists in thinking about connections between things and plan experiments to match.

- Focusing Investigations: Hypotheses help scientists focus on certain parts of their study question by clearly saying what they expect links or results to be. This focus makes the study work better.

- Facilitating Communication: Theories help scientists talk to each other effectively. Clearly made guesses help scientists to tell others what they plan, how they will do it and the results expected. This explains things well with colleagues in a wide range of audiences.

- Generating Testable Statements: A good guess can be checked, which means it can be looked at carefully or tested by doing experiments. This feature makes sure that guesses add to the real information used in science knowledge.

- Promoting Objectivity: Guesses give a clear reason for study that helps guide the process while reducing personal bias. They motivate scientists to use facts and data as proofs or disprovals for their proposed answers.

- Driving Scientific Progress: Making, trying out and adjusting ideas is a cycle. Even if a guess is proven right or wrong, the information learned helps to grow knowledge in one specific area.

Researchers use hypotheses to put down their thoughts directing how the experiment would take place. Following are the steps that are involved in the scientific method:

- Initiating Investigations: Hypotheses are the beginning of science research. They come from watching, knowing what's already known or asking questions. This makes scientists make certain explanations that need to be checked with tests.

- Formulating Research Questions: Ideas usually come from bigger questions in study. They help scientists make these questions more exact and testable, guiding the study's main point.

- Setting Clear Objectives: Hypotheses set the goals of a study by stating what we think will happen between different things. They set the goals that scientists want to reach by doing their studies.

- Designing Experiments and Studies: Assumptions help plan experiments and watchful studies. They assist scientists in knowing what factors to measure, the techniques they will use and gather data for a proposed reason.

- Testing Predictions: Ideas guess what will happen in experiments or observations. By checking these guesses carefully, scientists can see if the seen results match up with what was predicted in each hypothesis.

- Analysis and Interpretation of Data: Hypotheses give us a way to study and make sense of information. Researchers look at what they found and see if it matches the guesses made in their theories. They decide if the proof backs up or disagrees with these suggested reasons why things are happening as expected.

- Encouraging Objectivity: Hypotheses help make things fair by making sure scientists use facts and information to either agree or disagree with their suggested reasons. They lessen personal preferences by needing proof from experience.

- Iterative Process: People either agree or disagree with guesses, but they still help the ongoing process of science. Findings from testing ideas make us ask new questions, improve those ideas and do more tests. It keeps going on in the work of science to keep learning things.

People Also View:

Mathematics Maths Formulas Branches of Mathematics

Hypothesis is a testable statement serving as an initial explanation for phenomena, based on observations, theories, or existing knowledge . It acts as a guiding light for scientific research, proposing potential relationships between variables that can be empirically tested through experiments and observations.

The hypothesis must be specific, testable, falsifiable, and grounded in prior research or observation, laying out a predictive, if-then scenario that details a cause-and-effect relationship. It originates from various sources including existing theories, observations, previous research, and even personal curiosity, leading to different types, such as simple, complex, directional, non-directional, null, and alternative hypotheses, each serving distinct roles in research methodology .

The hypothesis not only guides the research process by shaping objectives and designing experiments but also facilitates objective analysis and interpretation of data , ultimately driving scientific progress through a cycle of testing, validation, and refinement.

Hypothesis - FAQs

What is a hypothesis.

A guess is a possible explanation or forecast that can be checked by doing research and experiments.

What are Components of a Hypothesis?

The components of a Hypothesis are Independent Variable, Dependent Variable, Relationship between Variables, Directionality etc.

What makes a Good Hypothesis?

Testability, Falsifiability, Clarity and Precision, Relevance are some parameters that makes a Good Hypothesis

Can a Hypothesis be Proven True?

You cannot prove conclusively that most hypotheses are true because it's generally impossible to examine all possible cases for exceptions that would disprove them.

How are Hypotheses Tested?

Hypothesis testing is used to assess the plausibility of a hypothesis by using sample data

Can Hypotheses change during Research?

Yes, you can change or improve your ideas based on new information discovered during the research process.

What is the Role of a Hypothesis in Scientific Research?

Hypotheses are used to support scientific research and bring about advancements in knowledge.

Similar Reads

- Mathematics

- Geeks Premier League

- School Learning

- Geeks Premier League 2023

- Maths-Class-12

Improve your Coding Skills with Practice

What kind of Experience do you want to share?

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

In research, a hypothesis is a clear, testable statement predicting the relationship between variables or the outcome of a study. Hypotheses form the foundation of scientific inquiry, providing a direction for investigation and guiding the data collection and analysis process. Hypotheses are typically used in quantitative research but can also inform some qualitative studies by offering a preliminary assumption about the subject being explored.

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction or statement that suggests an expected relationship between variables in a study. It acts as a starting point, guiding researchers to examine whether their predictions hold true based on collected data. For a hypothesis to be useful, it must be clear, concise, and based on prior knowledge or theoretical frameworks.

Key Characteristics of a Hypothesis :

- Testable : Must be possible to evaluate or observe the outcome through experimentation or analysis.

- Specific : Clearly defines variables and the expected relationship or outcome.

- Predictive : States an anticipated effect or association that can be confirmed or refuted.

Example : “Increasing the amount of daily physical exercise will lead to a reduction in stress levels among college students.”

Types of Hypotheses

Hypotheses can be categorized into several types, depending on their structure, purpose, and the type of relationship they suggest. The most common types include null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis , directional hypothesis , and non-directional hypothesis .

1. Null Hypothesis (H₀)

Definition : The null hypothesis states that there is no relationship between the variables being studied or that any observed effect is due to chance. It serves as the default position, which researchers aim to test against to determine if a significant effect or association exists.

Purpose : To provide a baseline that can be statistically tested to verify if a relationship or difference exists.

Example : “There is no difference in academic performance between students who receive additional tutoring and those who do not.”

2. Alternative Hypothesis (H₁ or Hₐ)

Definition : The alternative hypothesis proposes that there is a relationship or effect between variables. This hypothesis contradicts the null hypothesis and suggests that any observed result is not due to chance.

Purpose : To present an expected outcome that researchers aim to support with data.

Example : “Students who receive additional tutoring will perform better academically than those who do not.”

3. Directional Hypothesis

Definition : A directional hypothesis specifies the direction of the expected relationship between variables, predicting either an increase, decrease, positive, or negative effect.

Purpose : To provide a more precise prediction by indicating the expected direction of the relationship.

Example : “Increasing the duration of daily exercise will lead to a decrease in stress levels among adults.”

4. Non-Directional Hypothesis

Definition : A non-directional hypothesis states that there is a relationship between variables but does not specify the direction of the effect.

Purpose : To allow for exploration of the relationship without committing to a particular direction.

Example : “There is a difference in stress levels between adults who exercise regularly and those who do not.”

Examples of Hypotheses in Different Fields

- Null Hypothesis : “There is no difference in anxiety levels between individuals who practice mindfulness and those who do not.”

- Alternative Hypothesis : “Individuals who practice mindfulness will report lower anxiety levels than those who do not.”

- Directional Hypothesis : “Providing feedback will improve students’ motivation to learn.”

- Non-Directional Hypothesis : “There is a difference in motivation levels between students who receive feedback and those who do not.”

- Null Hypothesis : “There is no association between diet and energy levels among teenagers.”

- Alternative Hypothesis : “A balanced diet is associated with higher energy levels among teenagers.”

- Directional Hypothesis : “An increase in employee engagement activities will lead to improved job satisfaction.”

- Non-Directional Hypothesis : “There is a relationship between employee engagement activities and job satisfaction.”

- Null Hypothesis : “The introduction of green spaces does not affect urban air quality.”

- Alternative Hypothesis : “Green spaces improve urban air quality.”

Writing Guide for Hypotheses

Writing a clear, testable hypothesis involves several steps, starting with understanding the research question and selecting variables. Here’s a step-by-step guide to writing an effective hypothesis.

Step 1: Identify the Research Question

Start by defining the primary research question you aim to investigate. This question should be focused, researchable, and specific enough to allow for hypothesis formation.

Example : “Does regular physical exercise improve mental well-being in college students?”

Step 2: Conduct Background Research

Review relevant literature to gain insight into existing theories, studies, and gaps in knowledge. This helps you understand prior findings and guides you in forming a logical hypothesis based on evidence.

Example : Research shows a positive correlation between exercise and mental well-being, which supports forming a hypothesis in this area.

Step 3: Define the Variables

Identify the independent and dependent variables. The independent variable is the factor you manipulate or consider as the cause, while the dependent variable is the outcome or effect you are measuring.

- Independent Variable : Amount of physical exercise

- Dependent Variable : Mental well-being (measured through self-reported stress levels)

Step 4: Choose the Hypothesis Type

Select the hypothesis type based on the research question. If you predict a specific outcome or direction, use a directional hypothesis. If not, a non-directional hypothesis may be suitable.

Example : “Increasing the frequency of physical exercise will reduce stress levels among college students” (directional hypothesis).

Step 5: Write the Hypothesis

Formulate the hypothesis as a clear, concise statement. Ensure it is specific, testable, and focuses on the relationship between the variables.

Example : “College students who exercise at least three times per week will report lower stress levels than those who do not exercise regularly.”

Step 6: Test and Refine (Optional)

In some cases, it may be necessary to refine the hypothesis after conducting a preliminary test or pilot study. This ensures that your hypothesis is realistic and feasible within the study parameters.

Tips for Writing an Effective Hypothesis

- Use Clear Language : Avoid jargon or ambiguous terms to ensure your hypothesis is easily understandable.

- Be Specific : Specify the expected relationship between the variables, and, if possible, include the direction of the effect.

- Ensure Testability : Frame the hypothesis in a way that allows for empirical testing or observation.

- Focus on One Relationship : Avoid complexity by focusing on a single, clear relationship between variables.

- Make It Measurable : Choose variables that can be quantified or observed to simplify data collection and analysis.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Vague Statements : Avoid vague hypotheses that don’t specify a clear relationship or outcome.

- Unmeasurable Variables : Ensure that the variables in your hypothesis can be observed, measured, or quantified.

- Overly Complex Hypotheses : Keep the hypothesis simple and focused, especially for beginner researchers.

- Using Personal Opinions : Avoid subjective or biased language that could impact the neutrality of the hypothesis.

Examples of Well-Written Hypotheses

- Psychology : “Adolescents who spend more than two hours on social media per day will report higher levels of anxiety than those who spend less than one hour.”

- Business : “Increasing customer service training will improve customer satisfaction ratings among retail employees.”

- Health : “Consuming a diet rich in fruits and vegetables is associated with lower cholesterol levels in adults.”

- Education : “Students who participate in active learning techniques will have higher retention rates compared to those in traditional lecture-based classrooms.”

- Environmental Science : “Urban areas with more green spaces will report lower average temperatures than those with minimal green coverage.”

A well-formulated hypothesis is essential to the research process, providing a clear and testable prediction about the relationship between variables. Understanding the different types of hypotheses, following a structured writing approach, and avoiding common pitfalls help researchers create hypotheses that effectively guide data collection, analysis, and conclusions. Whether working in psychology, education, health sciences, or any other field, an effective hypothesis sharpens the focus of a study and enhances the rigor of research.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Trochim, W. M. K. (2006). The Research Methods Knowledge Base (3rd ed.). Atomic Dog Publishing.

- McLeod, S. A. (2019). What is a Hypothesis? Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-a-hypotheses.html

- Walliman, N. (2017). Research Methods: The Basics (2nd ed.). Routledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and...

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates...

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and...

COMMENTS

An empirical hypothesis is the opposite of a logical hypothesis. It is a hypothesis that is currently being tested using scientific analysis. We can also call this a 'working hypothesis'. We can to separate research into two types: theoretical and empirical. Theoretical research relies on logic and thought experiments.

For example, "There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B" is a non-directional hypothesis. Directional Hypothesis. A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place.

Null Hypothesis (H0) Null hypothesis is a statement that says there's no connection or difference between different things. It implies that any seen impacts are because of luck or random changes in the information. Example: The average test scores of Group A and Group B are not much different.

The alternative hypothesis (H a) is the other answer to your research question. It claims that there's an effect in the population. Often, your alternative hypothesis is the same as your research hypothesis. In other words, it's the claim that you expect or hope will be true. The alternative hypothesis is the complement to the null hypothesis.

Simple hypothesis: This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.; Complex hypothesis: This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.; Null hypothesis: This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

Hypothesis B is not testable because scientific hypotheses are not value statements; they do not include judgments like "should," "better than," etc. Scientific evidence certainly might support this value judgment, but a hypothesis would take a different form: "Having unprotected sex with many partners increases a person's risk for ...

Hypothesis. A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction or statement that suggests an expected relationship between variables in a study. It acts as a starting point, guiding researchers to examine whether their predictions hold true based on collected data. For a hypothesis to be useful, it must be clear, concise, and based on prior knowledge or theoretical frameworks.

6. Write a null hypothesis. If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing, you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0, while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a.

The null hypothesis, denoted as H 0, is the hypothesis that the sample data occurs purely from chance. The alternative hypothesis, denoted as H 1 or H a, is the hypothesis that the sample data is influenced by some non-random cause. Hypothesis Tests. A hypothesis test consists of five steps: 1. State the hypotheses. State the null and ...

4 Alternative hypothesis. An alternative hypothesis, abbreviated as H 1 or H A, is used in conjunction with a null hypothesis. It states the opposite of the null hypothesis, so that one and only one must be true. Examples: Plants grow better with bottled water than tap water. Professional psychics win the lottery more than other people. 5 ...