Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Chapter 3: Traditional African Religious Beliefs and Practices

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation

- Chapter 2: Commitment to Christianity and Islam

- Chapter 4: Interreligious Harmony and Tensions

- Chapter 5: Religion and Society

- About the Project

Side by side with their high levels of commitment to Christianity and Islam, many people in the countries surveyed retain beliefs and rituals that are characteristic of traditional African religions. In four countries, for instance, half or more of the population believes that sacrifices to ancestors or spirits can protect them from harm. In addition, roughly a quarter or more of the population in 11 countries say they believe in the protective power of juju (charms or amulets), shrines and other sacred objects. Belief in the power of such objects is highest in Senegal (75%) and lowest in Rwanda (5%). (See the glossary for more information on juju.)

In addition to expressing high levels of belief in the protective power of sacrificial offerings and sacred objects, upwards of one-in-five people in every country say they believe in the evil eye, or the ability of certain people to cast malevolent curses or spells. In five countries (Tanzania, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Senegal and Mali) majorities express this belief. (See the glossary for more information on the evil eye.)

In most countries surveyed, at least three-in-ten people believe in reincarnation, which may be related to traditional beliefs in ancestral spirits. The conviction that people will be reborn in this world again and again tends to be more common among Christians than Muslims.

The continued influence of traditional African religion is also evident in some aspects of daily life. For example, in 14 of the 19 countries surveyed, more than three-in-ten people say they sometimes consult traditional healers when someone in their household is sick. This includes five countries (Cameroon, Chad, Guinea Bissau, Mali and Senegal) where more than half the population uses traditional healers. While the recourse to traditional healers may be motivated in part by economic reasons and an absence of health care alternatives, it may also be rooted in religious beliefs about the efficacy of this approach.

This chapter includes information on:

- Traditional African religious beliefs, such as belief in the protective power of sacrifices to ancestors

- Traditional African religious practices, such as owning sacred objects

Download chapter 3 in full (3-page PDF, <1MB)

Photo credit: Sebastien Desarmaux/GODONG/Godong/Corbis

Part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- Christianity

- Comparison of Religions

- Global Religious Demographics

- Interreligious Relations

- Muslims Around the World

- Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

- Religion & Politics

- Size & Demographic Characteristics of Religious Groups

8 in 10 Americans Say Religion Is Losing Influence in Public Life

Faith on the hill, in their own words: how americans describe ‘christian nationalism’, pastors often discussed election, pandemic and racism in fall of 2020, most democrats and republicans know biden is catholic, but they differ sharply about how religious he is, most popular, report materials.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section African Traditional Religion

Introduction, general overviews.

- Proponents of African Traditional Religion

- Land and Ancestors

- Symbolism, Intellect, Imagination

- Belief and Practice

- Translation

- The Category “Religion”

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- African Christianity

- Health, Medicine, and the Study of Africa

- Islam in Africa

- Music, Dance, and the Study of Africa

- Social and Cultural Anthropology and the Study of Africa

- The Great Lakes States of Eastern Africa

- Women and Colonialism

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Commodity Trade

- Electricity

- Trade Unions

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

African Traditional Religion by Wyatt MacGaffey , Mariam Goshadze LAST REVIEWED: 23 June 2023 LAST MODIFIED: 23 June 2023 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199846733-0064

The term “African Traditional Religion” is used in two complementary senses. Loosely, it encompasses all African beliefs and practices that are considered religious but neither Christian nor Islamic. The expression is also used almost as a technical term for a particular reading of such beliefs and practices, one that purports to show that they constitute a systematic whole—a religion comparable to Christianity or any other “world religion.” In that sense the concept was new and radical when it was introduced by G. Parrinder in 1954 and later developed by Bolaji Idowu and John Mbiti (see Proponents of African Traditional Religion ). The intention of these scholars was to protest against a long history of derogatory evaluations of Africans and their culture by outsiders and to replace words such as “heathenism” and “paganism.” African Traditional Religion is now widely taught in African universities, but its identity remains essentially negative: African belief that is not Christianity or Islam. To understand the issue, one must go back to the beginnings of anthropology in the nineteenth century and follow its evolution (see 19th-Century Background ). As the European empires in Africa began to break up after World War II, both missionaries and African nationalists sought to defend Africans and African culture from their reputation for primitivism and to claim parity with Christianity, the West, and the modern world. At the same time a movement that began after World War I and intensified after World War II supported the idea that Africans retained values that the militaristic and materialistic modern world had lost, and that Africans individually and collectively were spiritual people. Such generalizations have been challenged by scholars who say that Africa is too diverse to support these notions. Ethnographic studies contradict the simplicities of African Traditional Religion and reveal the complex relations of religion with politics, economics, and social structure ( Ethnography ). A more radical challenge has been mounted recently by anthropologists and historians who argue that the concept of religion itself has been defined in implicitly Christian terms and that the collection of data to be treated as “religion” depends on an implicit Judeo-Christian template that often radically mistranslates and misrepresents African words and practices (see Criticism ). Certain religious topics have proved perennially fascinating to both scholars and the reading public with reference to the world as a whole, not just Africa. They include “witchcraft,” “symbolism,” and “ancestor worship.” These topics, lending themselves to exoticism, give rise in acute form to the problems of intercultural misunderstanding. “Healing,” on the other hand, sounds familiar and beneficial, although in practice what is called “healing” is often far removed from Western ideas of sickness and medicine.

African Traditional Religion is a thriving scholarly business, but a serious disconnect exists between contributions that celebrate a generalized African Traditional Religion and those that describe particular religions and aspects of religion on the basis of ethnographic and archival research. The generalizations begin by citing allegedly negative characterizations of African culture: it is argued that African beliefs and practices are misunderstood and unjustly condemned, that Africans are everywhere and always profoundly religious, and that their religion or religions are comparable to religions anywhere else. On the other hand, historians and anthropologists, skeptical with regard to abstractions and generalizations, focus on the religion of particular peoples to show how belief and practice fit into everyday life. They struggle with epistemological questions such as, “On what evidentiary basis can an individual or group be said to “believe” in anything?” There is little dialogue between the two points of view, but the readings suggested in this section reveal some of the differences. Chidi Denis Isizoh’s website carries links to a variety of essays on traditional religion and its relations with Christianity and Islam; it also includes Ejizu’s overview ( Emergent Key Issues in the Study of African Traditional Religions ). More and more materials are available on the Internet, notably at African Traditional Religion , but not all of it should be regarded as representative or authoritative. Journals such as the London-based Africa , Cahiers d’Études Africaines (Paris), and the Journal of Religion in Africa (Leiden, The Netherlands) publish articles on religion from time to time, representing the latest thinking. The edited collections Blakely, et al. 1994 ; Olupona and Nyang 1993 ; and Olupona 2000 provide essays on specific examples of African religion by leading scholars, while implicitly illustrating the gap between “spiritual” and “ethnographic” approaches. A handbook of African Traditional Religion, Aderibigbe and Falola 2022 offers the most comprehensive thematic overview of the nature, structure, and significance of African religion to date. Olupona 2014 , on the other hand, is the perfect introduction to the religions of Africa for those who are not familiar with the topic. This literature, however, does not actively engage with the radical objections raised in Criticism concerning the definition of religion, the errors introduced by intercultural translation, and the depth of outside influence on supposedly timeless “traditional religion.”

Aderibigbe, Ibigbolade S., and Toyin Falola, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Traditional African Religion . Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

A comprehensive collection of thematically arranged articles on African Traditional Religion written by scholars from various disciplines designed for students, scholars, and the general public interested in the subject. The volume seeks to not only define critical issues that are essential for understanding African religions, but also to stress their dynamic nature and continuous relevance. The authors are building on a homogenized notion of Traditional Religion as a singular religious tradition of Africa.

Africa . 1928–.

The venerable journal of the International African Institute offers academic articles on all aspects of African history and culture, including religion.

African Traditional Religion . Africa South of the Sahara.

An idiosyncratic collection of sources from professional to popular.

Blakely, Thomas D., Walter E. A. van Beek, and Dennis L. Thomson, eds. Religion in Africa . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1994.

A wide-ranging symposium with contributions by major specialists in the field. Unlike Olupona’s collections ( Olupona and Nyang 1993 , Olupona 2000 ), this one does not presume or discuss “African spirituality.” One of the three sections deals with “religion and its translatability,” a topic and a problem of concern to both missionaries and anthropologists.

Cahiers d’Études Africaines . 1960–.

Offers articles in French and English on all aspects of African culture, often manifesting a distinctly French intellectual approach.

Emergent Key Issues in the Study of African Traditional Religions .

A historical review and critique of the subject and of major problems and disagreements associated with it, written by Christopher Ejizu. The review suggests that the defensive tone of much writing about African Traditional Religion is directed against outdated studies that no one takes seriously anymore. The main website African Traditional Religions , maintained by Chidi Denis Isizoh, is a useful guide to further reading.

Grillo, Laura S., Adriaan van Klinken, and Hassan J. Ndzovu. Religions in Contemporary Africa: An Introduction . New York: Routledge, 2019.

DOI: 10.4324/9781351260725

Building on the premise that Africans are exceedingly religious, the authors map out the religious scenery of modern Africa. The book is enlightening for those who want to understand the exchange between traditional religions of Africa and Christianity and Islam, especially the former’s influence on the latter. The text is designed for students and offers useful tools for instructors, such as discussion questions and short case studies.

Journal of Religion in Africa . 1967–.

Scholarly articles on Islam and on Christian and non-Christian religious diasporas. An excellent source for insights into contemporary scholarly issues and approaches.

Olupona, Jacob K. African Religions: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

DOI: 10.1093/actrade/9780199790586.001.0001

A concise and easily digestible overview of Africa’s religions. While traditional religions are at the center of the analysis, due attention is paid to the rise of Christianity and Islam on the continent. Olupona captures the enormous range of cultures, peoples, and religious practices across Africa, touching on basic beliefs, rites, and celebrations of African religions.

Olupona, Jacob K., ed. African Spirituality: Forms, Meanings and Expressions . New York: Crossroad, 2000.

Olupona identifies African spirituality in myth, and ritual as that which “expresses the relationship between human being and divine being” (p. xvi). Leading scholars cover a wide range of topics and religious practices, including Islam and 3rd-century North African Christianity, rarely questioning the concept of spirituality itself.

Olupona, Jakob K., and Sulayman S. Nyang, eds. Religious Plurality in Africa: Essays in Honour of John S. Mbiti . Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1993.

A collection representative of the “religio-phenomenological” approach to comparative religion, theology, and philosophy, in which religion is conceived of as a phenomenon sui generis, “the transcendent” is universally recognized, and religions are presented in isolation from their cultural and historical contexts. Two chapters concern Islam in Africa.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About African Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Achebe, Chinua

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi

- Africa in the Cold War

- African Masculinities

- African Political Parties

- African Refugees

- African Socialism

- Africans in the Atlantic World

- Agricultural History

- Aid and Economic Development

- Arab Spring

- Arabic Language and Literature

- Archaeology and the Study of Africa

- Archaeology of Central Africa

- Archaeology of Eastern Africa

- Archaeology of Southern Africa

- Archaeology of West Africa

- Architecture

- Art, Art History, and the Study of Africa

- Arts of Central Africa

- Arts of Western Africa

- Asante and the Akan and Mossi States

- Bantu Expansion

- Benin (Dahomey)

- Botswana (Bechuanaland)

- Brink, André

- British Colonial Rule in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Burkina Faso (Upper Volta)

- Business History

- Central African Republic

- Children and Childhood

- China in Africa

- Christianity, African

- Cinema and Television

- Citizenship

- Coetzee, J.M.

- Colonial Rule, Belgian

- Colonial Rule, French

- Colonial Rule, German

- Colonial Rule, Italian

- Colonial Rule, Portuguese

- Communism, Marxist-Leninism, and Socialism in Africa

- Comoro Islands

- Conflict in the Sahel

- Conflict Management and Resolution

- Congo, Republic of (Congo Brazzaville)

- Congo River Basin States

- Conservation and Wildlife

- Coups in Africa

- Crime and the Law in Colonial Africa

- Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire)

- Development of Early Farming and Pastoralism

- Diaspora, Kongo Atlantic

- Disease and African Society

- Early States And State Formation In Africa

- Early States of the Western Sudan

- Eastern Africa and the South Asian Diaspora

- Economic Anthropology

- Economic History

- Economy, Informal

- Education and the Study of Africa

- Egypt, Ancient

- Environment

- Environmental History

- Equatorial Guinea

- Ethnicity and Politics

- Europe and Africa, Medieval

- Family Planning

- Farah, Nuruddin

- Food and Food Production

- Fugard, Athol

- Genocide in Rwanda

- Geography and the Study of Africa

- Gikuyu (Kikuyu) People of Kenya

- Globalization

- Gordimer, Nadine

- Great Lakes States of Eastern Africa, The

- Guinea-Bissau

- Hausa Language and Literature

- Historiography and Methods of African History

- History and the Study of Africa

- Horn of Africa and South Asia

- Ijo/Niger Delta

- Image of Africa, The

- Indian Ocean and Middle Eastern Slave Trades

- Indian Ocean Trade

- Invention of Tradition

- Iron Working and the Iron Age in Africa

- Islamic Politics

- Kongo and the Coastal States of West Central Africa

- Language and the Study of Africa

- Law and the Study of Sub-Saharan Africa

- Law, Islamic

- LGBTI Minorities and Queer Politics in Eastern and Souther...

- Literature and the Study of Africa

- Lord's Resistance Army

- Maasai and Maa-Speaking Peoples of East Africa, The

- Media and Journalism

- Modern African Literature in European Languages

- Music, Traditional

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

- North Africa from 600 to 1800

- North Africa to 600

- Northeastern African States, c. 1000 BCE-1800 CE

- Obama and Kenya

- Oman, the Gulf, and East Africa

- Oral and Written Traditions, African

- Ousmane Sembène

- Pastoralism

- Police and Policing

- Political Science and the Study of Africa

- Political Systems, Precolonial

- Popular Culture and the Study of Africa

- Popular Music

- Population and Demography

- Postcolonial Sub-Saharan African Politics

- Religion and Politics in Contemporary Africa

- Sexualities in Africa

- Seychelles, The

- Slave Trade, Atlantic

- Slavery in Africa

- São Tomé and Príncipe

- South Africa Post c. 1850

- Southern Africa to c. 1850

- Soyinka, Wole

- Spanish Colonial Rule

- States of the Zimbabwe Plateau and Zambezi Valley

- Sudan and South Sudan

- Swahili City-States of the East African Coast

- Swahili Language and Literature

- Tanzania (Tanganyika and Zanzibar)

- Traditional Authorities

- Traditional Religion, African

- Transportation

- Trans-Saharan Trade

- Urbanism and Urbanization

- Wars and Warlords

- Western Sahara

- White Settlers in East Africa

- Women and African History

- Women and Politics

- Women and Slavery

- Women and the Economy

- Women, Gender and the Study of Africa

- Women in 19th-Century West Africa

- Yoruba Diaspora

- Yoruba Language and Literature

- Yoruba States, Benin, and Dahomey

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

Select Page

Jacob K. Olupona. HDS Photograph

As scholars of the comparative study of religions in Africa, we must begin to rethink the study of African religion in the twenty-first century in order to avoid the continuous mis-assessment of the resilience of indigenous traditions. Indigenous religions are definitive of the African identity, as African religion and cultures provide the language, the ethos, the knowledge, and the ontology that enable the proper formation of African personhood, communal identity, and values that constitute kernels of African ethnic assemblages. Consequently, despite all of Christianity and Islam’s claims to dominance and their propagandist machinery in demonizing indigenous religion, African religion still provides significant meaning to African existence in many ways. In this essay, I attempt to refocus the centrality of indigenous religion, not only in defining African cosmology and an African worldview, but also in defining the African personality in the twenty-first century.

What Is African Religion? The Big Question

The range of African indigenous beliefs and practices has been referred to as African traditional religions in an effort to encompass the breadth and depth of the religious traditions on the continent. 2 The diversity of the traditions themselves is tremendous, making it next to impossible for all of them to be captured in a single presentation. Even the word “religion,” used in reference to these traditions, is in itself problematic for many Africans, because it suggests that religion is separate from other aspects of one’s culture, society, and environment. For many Africans, religion is a way of life that can never be separated from the public sphere, but instead informs everything in traditional African society, including politics, art, marriage, health, diet, dress, economics, and death.

Despite the plethora of denominations and sects, African religions continue to be viewed as single entities, 3 and their (our) religions are perhaps the least understood facet of African life. Many foreigners who come to Africa become fascinated by ancestral spirits and spirits in general, as if the mystique of African religions is the only aspect of African spirituality that can hold scholarly interest. 4 There are several common features of African indigenous religions that suggest similar origins and allow African religions to be treated as a single religious tradition, just as Christianity and Islam are.

First, there is a supreme being who created the universe and every living and nonliving thing to be found within the universe. Second, spirit beings occupy the next tier in the cosmology and constitute a pantheon of deities who often assist the supreme God in performing different functions. John Mbiti divides spirit beings into two types, nature spirits and human spirits. Each has a life force but no concrete physical form. Nature spirits are associated with objects seen in nature, such as mountains, the sun, or trees, or natural forces such as wind and rain. Human spirits represent people who have died, usually ancestors, in the recent or distant past. 5 Third, the world of the ancestors occupies a large part of African cosmology. As spirits, the ancestors are more powerful than living humans, and they continue to play a role in community affairs after their deaths, acting as intermediaries between God and those still living. 6 Finally, I would add that Africans live their faith rather than compartmentalize it into something to be practiced on certain days or in particular places. Catholic moral theologian Laurenti Magesa argues that, unlike clothes, which one can wear and take off, for Africans, religion is like skin that cannot be so easily abandoned. 7 Mbiti also captures this unique aspect in the following passage:

Because traditional religions permeate all the departments of life, there is no formal distinction between the sacred and the secular, between the religious and non-religious, between the spiritual and the material areas of life. Wherever the African is, there is his religion: he carries it to the fields where he is sowing seeds or harvesting a new crop; he takes it with him to the beer party or to attend a funeral ceremony; . . . Although many African languages do not have a word for religion as such, it nevertheless accompanies the individual from long before his birth to long after his physical death. Through modern change these traditional religions cannot remain intact, but they are by no means extinct. In times of crisis they often come to the surface, or people revert to them in secret. 8

The most difficult task I face in characterizing African indigenous spiritual traditions is accounting for their diversity and complexity. One approach is to outline, in a systematic way, the essential features of these traditions without paying much attention to whether or not the traditions fit into the pattern of religions already mapped out by Western theologians and historians, who use Western religious traditions as the standard by which to measure religions in other parts of the world. African religions should be studied on their own terms, examined through their own frames rather than set in a Judeo-Christian framework. Such an approach should endeavor to provide not only an awareness of sociocultural contexts but also to narrate the historical dimensions of these traditions.

Myths, Rituals, and Cosmologies

Narratives about the creation of the universe (cosmogony) and the nature and structure of the world (cosmology) provide a useful entry to understanding African religious life and worldviews. These narratives come to us in the form of “myths.” Unlike its popular usage, in scholarly language myths are sacred stories believed to be true by those who hold on to them. Myths reveal critical events and episodes—involving superhuman entities, gods, spirits, ancestors—that are of profound and transcendent significance to the African people who espouse them. As oral narratives, myths are passed from one generation to another and represented and reinterpreted by each generation, who then make the events revealed in the myths relevant and meaningful to their present situation. 9

In spite of the heuristic value of V. Y. Mudimbe’s distinction between myth and history in Africa, and by extension the cohesion of oral and written narratives, 10 the notion that myth is nonrational and unscientific while history is critical and rational is false. For one thing, a sizable number of African myths deal with events considered to have actually happened as narrated by the people themselves or as reformulated into symbolic expressions of historical events. Symbolic and mythic narratives may exist side by side with narratives of legends in history that bear similar characteristics with motifs and events of creation or coming to birth. On the other hand, we now know from research and archival sources that, by their very nature, sources and records of missionaries, colonial administrators, and indigenous elites, which were preserved by colonial administrations, were equally susceptible to distortion and perforation, having been written from the angle of an invented modernity that the colonizer considered superior to the worldviews of local peoples.

A sizable number of African myths deal with events considered to have actually happened as narrated by the people themselves or as reformulated into symbolic expressions of historical events.

As with myths the world over, African mythology includes multiple, often contradictory, versions of the same event. African cosmogonic narratives posit the creation of a universe and the birth of a people and their indigenous religions. These are also stories about how the world was put into place by a divine power, usually a supreme god, but in collaboration with other lesser supernatural beings or deities, who act on his behalf or aid in the creative process. 11 The mechanisms and techniques of creation vary from story to story and from one tradition to another. While scholars have often argued that African indigenous accounts of creation were ex nihilo (created out of nothing), as the biblical account of creation is often portrayed, 12 African cosmological narratives generally indicate that there is never one pattern governing how creation happens. All over the continent, cosmological myths describe a complicated process, whether the universe evolves from preexisting objects or from God’s mere thought or speech. In whatever way it happens, African cosmological narratives are similarly complex, unsystematized, and multivariate, and they are the bedrock for indigenous value systems. Even within a single ethnic group or clan, there are often highly contested and even opposing stories or viewpoints when it comes to creation accounts, thus allowing for flexibility and hermeneutic creativity. The absence of centralized and unified cosmologies indicates the multifaceted nature of African religious life and worldviews.

Although it is difficult to generalize about African traditional cosmology and worldviews, a common denominator among them is a three-tiered model in which the human world exists sandwiched between the sky and the earth (including the underworld)—a schema that is not unique to Africa but is found in many of the world’s religious systems as well. A porous border exists between the human realm and the sky, which belongs to the gods. Similarly, although ancestors dwell inside the earth, their activities also interject into human life, which is why they are referred to as the living dead. 13 African cosmologies, therefore, portray the universe as a fluid, active, and impressionable space, with agents from each realm bearing the capabilities of traveling from one realm to another at will. In this way, the visible and invisible are in tandem, leading practitioners to speak about all objects, whether animate or inanimate, as potentially sacred on some level.

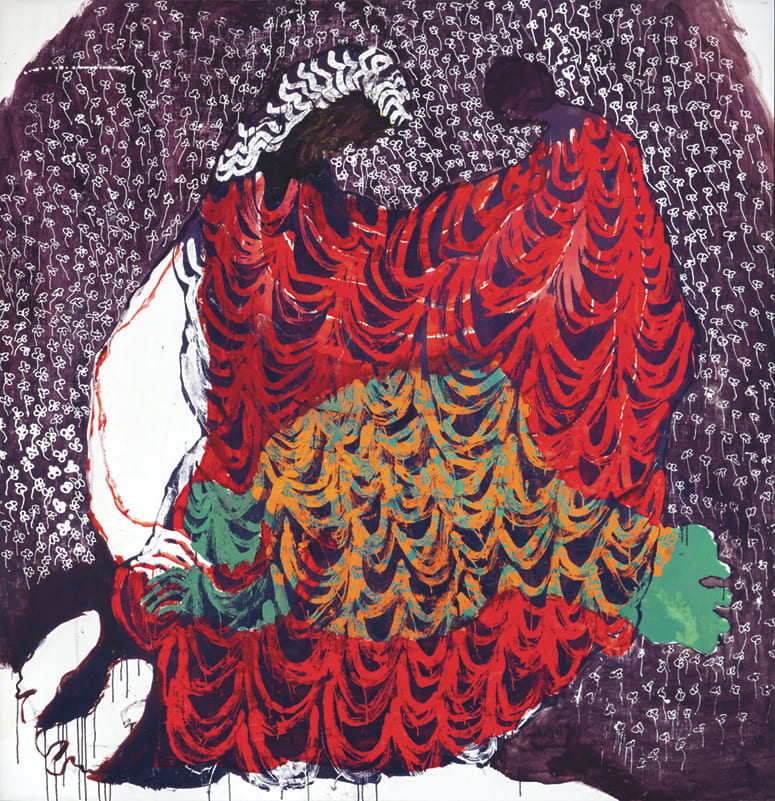

Portia Zvavahera , His Presence , 2013, oil-based printing ink on paper. Courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg

As a lived religion, African tradition deploys through its ritual processes—particularly rites of passage, calendrical rituals, and divinatory practices—tangible material and nonmaterial phenomena to regulate life events and occurrences, in order to ensure communal well-being. African religion supplies knowledge to live by and also a transfer of tradition, worldview, ethical orientation (principles of what is right or wrong), an ontology—a way of life. Hence, the aforementioned rituals are the entry point not only for an understanding of African tradition and religions but also for the visible manifestations and essence of African religious traditions.

As many might know, one type of ritual—initiations for adolescent African girls—causes great consternation among Westerners, because these often involve rites like female circumcision or other bodied practices. Female circumcision is a hotly contested practice condemned by many global organizations and lumped together under the category of “female genital mutilation.” Few have much clarity or knowledge on what is actually involved. Most importantly, the rite itself should not be condemned together with circumcision or female genital mutilation. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the practice, it is important to note that not all female initiations involve circumcision, and that the rituals associated with initiation are crucial to ensuring that an individual’s social position is affirmed by both family and community. For this reason, in many parts of Africa, the communal aspects of such rituals have been retained, due to their salience, while the circumcision practice has been dispensed with altogether, due to the health risks associated with it; this is the case among the Maasai in Kenya and in Somali culture, both in Djibouti and Somalia.

African traditional religions are structured very differently from Western religions in that there is relatively little formal structure. African religions do not rely on a single individual to be a religious leader, but rather depend on an entire community to make the religion work. Priests, priestesses, and diviners are among the authorities who perform religious ceremonies, but the hierarchical structure is often very loose. Depending on the kind of religious activity being performed, different religious authorities can be leaders for specific events. The cosmological structure, however, is much more defined and precise.

African religions are, therefore, a praxis, and this is where the focus of study should mostly be directed. They provide the orientation for the human life journey by defining the rites of passage from life to death. Every life stage is important in African religions, from birth and naming, to betrothal/marriage, elderhood, and eventually death. Each transition has a function within the society. Due to the centrality of ancestral tradition to the African lifeworld, death itself is a significant transition from the current life to the afterlife and marks a continuity in life for those living and those to come. There are rituals that celebrate the passage of time and mark time as it passes for the people, orienting them to the seasonal changes, such as the new yam festival and celebration of the old season and beginning of a new one.

Sacred Kingship and Civil Religion

African spirituality more generally—and Nigerian spirituality in particular—is shaped by how individuals in their daily existence make sense of their interactions with religious experience. In my work, I consider civil religion in Nigeria as a central galvanizing feature that brings together different aspects of religious beingness under the banner of sacred kingship. My earlier scholarship was propelled by the insight that the ideology and rituals of Yoruba sacred kingship are what define Yoruba civil religion and, indeed, the center of Yoruba identity. 15 Sociologist Robert Bellah understands civil religion as the sacred principle and central ethic that unites a people, without which societies cannot function. 16 Civil religion incorporates common myths, history, values, and symbols that relate to a society’s sense of collective identity. In the case of the Yoruba kings and their people, sacred kingship formed a sacred canopy that sheltered the followers of each of the three major traditions—Islam, Christianity, and African traditional religion—forging bonds of community identity among followers of the different traditions.

Later in my academic life, I explored theoretical issues at the national level, showing how Nigerian civil religion—an invisible faith—provided a template for assessing how we fared at nation building, allowing the symbols of Nigerian nationhood to take on religious significance for the Nigerian public above and beyond any particular cultural communities of faith. 17 I do not want to be misunderstood here. Advocating for civil religion in a religiously pluralistic society does not require the erasure of conventional religious traditions. Rather, institutional religion continues to grow in relevance and in the national imagination, whether its invocations are part of conversations concerning nation building, Maitatsine and Boko Haram violence, the secularism debate, the Shar’ia debate, the question of Islamic banking, or the role of the Organization of Islamic Conference. By civil religion, I have in mind not only institutional religion and the beliefs and practices as they relate to the sacred and transcendent, but also practices not always defined as religious, including the rites of passage offered by our various youth brigades, and also the values of communalism and national sacrifice. Religion also encompasses the human, cultural dimensions within faith traditions, such as how human agency shapes, influences, and complicates religious control. Thus, I have argued that religion should be examined not only as a sacred phenomenon, but also as a cultural and human reality, all the while remembering the importance of integrating the sociopolitical dimensions of religiosity into any examination of an African state.

Indigenous religion has always played a pivotal role in the African public sphere, as my study of the Ifa divination system has shown. 18 In indigenous religion, communities are governed according to the dictates of the gods, particularly through a divination system such as Fa (Benin) and Ifa (Southwest Nigeria), which encompass the political, social, and economic conditions of life. In my research into Ifa narratives, I showed how, in the Ifa worldview, a traditional banking system was created and made possible when Aje, a Yoruba goddess of wealth, visited Orunmila, god of divination, to seek tips on how to keep robbers from stealing her spurious wealth, for which the added task of securing it was becoming quite burdensome. It was through this encounter that the Yoruba system of banking money in traditional pots kept underground in farms and forests began. What is fascinating about this odu (Ifa text) is that it supports a key and cardinal principle of Ifa tradition—that we seek counsel first, before we perform divination ( Imoram la nda ki a to da Ifa ). The diviner, therefore, is also a counselor, psychologist, medicine man or woman, and the spiritual guardian of villages and towns.

Ifa defines Yoruba humanity, providing responses to critical issues of its communities.

The Ifa divination system, which produced 256 chapters of oral narratives, constitutes an encyclopedic compendium of knowledge that provides answers to nearly every meaningful human question in the Yoruba and Fon universe. Ifa defines Yoruba humanity, providing responses to critical issues of its communities. Ironically, this pivotal source of knowledge and spiritual edifice—that modern-day Yoruba reject as constituting paganism—is the cornerstone of global Orisa traditions in Brazil, Cuba, and the Caribbean.

Divination enables us to recognize how indigenous traditions have a foundation upon which knowledge and knowledge production is developed. We must be careful not to give the impression that African religious lives are compartmentalized into what is often called the triple heritage (Islam, Christianity, and African traditional religion). In the lived experiences of the people, there has been much borrowing and interchange, particularly in those places that have a history of peaceful coexistence among diverse religious traditions, as is so among the Yoruba. However, African indigenous religion has not only succeeded in domesticating Islam and Christianity; in many instances, it has absorbed aspects of these two other traditions into its cosmology and narrative accounts and practices. A classic example is how the Ifa divination text of the Yoruba provides deep commentary on the practice of Islam by the Yoruba people, such as the hajj tradition. In one particular odu of Ifa, Ifa informs us and, correctly so, that the most cardinal event of the hajj is the climbing of Mount Arafat (Oke Arafa). In response to this verse, Ifa defines its own pilgrimage tradition in the rituals of the climbing of Oke Itase (Ifa Hill), the home of Ifa, when the Araba of Ifa in quiet solitude leads the devotee to the top of the sacred temple of Ifa. As in the Muslim pilgrimage, it is a solemn journey to the hilltop. An Ifa song warns those embarking on the pilgrimage to be pure and those who possess witchcraft not to embark on the pilgrimage.

Gender and the Role of Women

Another false impression often given about African religions is that women do not play any central or leadership roles in the performance of African religious traditions. This is far from the truth. Gender dynamics are important in African indigenous religions and in cultural systems, so much so that women goddesses and women-invented rituals are commonplace. Women constitute a sizable number of the devotees of these traditions, just as they do in Islam and Christianity. One of the more fascinating conversations that has emerged in the debate about African indigenous traditions is about the central role of women as bearers and transmitters of the traditions, and also the negotiation of gender dynamics. Compared to most patriarchal traditions, where women’s participation and roles are curtailed, African religions’ attitude toward gender inclusion is unique. In certain contexts and communities we have many documented instances of the central role of goddesses as founders of traditions, builders of kingdoms, and saviors and defenders of cities and civilizations—for example, Moremi in Yorubaland, Nzinga in Angola, and Osun in West Africa.

Women are revered in African traditions as essential to the cosmic balance of the world. As the late African historian Cheikh Anta Diop argued, matriarchy was embedded in the African way of life. Inasmuch as androcentric authority is more prominent within social structures and systems and patriarchy is more pronounced in the social order, women are considered the cornerstone of the African family system. 19 The African mother is a vibrant life force, central to African religious understandings of the interrelatedness between the human and the divine, as she embodies the production and sustaining of life. Thus, many practitioners of African religion, particularly in the shrines of goddesses, are women, indicating the parity with which African religion treats gender and gender-related issues. African American women are turning more and more to goddess religions and Orisa practices, as they find African religion offering them greater religious autonomy than other Western religions.

African Religion in the Creation of African Diasporic Religions

Another crucial aspect to consider in the comparative study of African religions is the reality of the transfer of these religions across the Atlantic through the Middle Passage and transnational migration and cultural exchange. The formation of African diasporic religions in the crucible of forced and voluntary migrations of Africans from the continent from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries led to the intermingling of African religions with Christianity and local cultures of the Transatlantic to form novel religious expressions. Religions of the African diaspora are of particular note and importance to the comparative study of African religions because of their resilience and the characteristic formations leading to their performance and expression. Religions such as Candomblé, Vodun, Santeria, and the Caribbean and Orisa tradition historically came about from African transactions with the new world and the old Euro-Christian worldview. Through their mixing, a new kind of religion emerged, forming the basis for what we have come to know as African diaspora religion.

Portia Zvavahera , Cosmic Prayer , 2019, oil-based printing ink and oil bar on canvas. Courtesy Of Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg

Why is this important to our understanding of African indigenous religions? Because it enables us to theorize questions of syncretism and hybridization and, more importantly, raises the issue of why African religion is flowering and spreading in the Americas, especially in the United States, while it is declining in Africa—a phenomenon that we need to understand. On the continent early modernizers assumed that African religion was part of the problem of the antimodernity project and that uprooting African indigenous religion would auger well for the modern African state. However, in the new world, we are seeing that the stone that the builders had rejected has become the cornerstone and central pillar: for example, Santeria was central to Cuban state making, and in Brazil only recently has Pentecostalism become responsible for the violence against Candomblé devotees.

African scholars in the United States are paying increasing attention to African images in African American culture and religion. 20 Some scholars, especially literary critics, now scout African American novels such as Toni Morrison’s and Alice Walker’s works, for glimpses of African traditions. Similarly, there are others like Henry Louis Gates who has appropriated images of the Yoruba deity of Esu in his own work. Significant as these studies are, there seems to be no systematic exploration of African traditions in African American culture. 21

African Religion and Interreligious Engagement and Research

Understanding the contours of traditions as they are today consists of picturing both what they are and what they can be against the backdrop of what they once were. Religious contexts are shaped and determined by the identity of these religions. Representation matters, and as scholars we have a responsibility to advocate for religions in their contexts. In the primordial era, various forms of ethnic indigenous religions spread across the African continent, providing cohesive foundations of nations, peoples, and religious worldviews. Based on sacred narratives, these traditions espoused their unique worldviews, defining cosmologies, ritual practices, sociopolitical frameworks, and ethical standards, as well as social and personal identity. Yet in the scholarship on the history of religions, indigenous African religions were never considered a substantive part of the world’s religious traditions, because they failed to fulfill certain criteria defined by axial age “civilization.” Privileged European scholars denied the agency of African religions and singled out—and thereby controlled—African identity. For example, James George Frazer (1854–1941) and Edward B. Tylor (1832–1917) classified indigenous religious practices of “natives” not as universally religious or generative of religious cultures but as forms of “primitive” religion or magic arising from the “lower” of three stages of human progress. These stages characterized European perceptions of human evolution. Such scholars stereotyped African religion—and African peoples themselves—as primitive social forms, part of a lower social order.

Indigenous traditions . . . creatively domesticated the new faiths, absorbing new rituals and tenets into their own belief systems.

Responding to this erasure of African indigenous religion as a productive and generative practice, scholars rallied in opposition. Bolaji Idowu, John Mbiti, Wande Abimbola, Benjamin Ray, Gabriel Setiloane, Laura Grillo, Aloysius Lugira, Kofi Asare Opoku, Emefie Ikenga-Metuh, Charles Long, and others attempted to imbue African traditions with the vitality, status, and identity that is now finally recognized. African religions command their own cultural ingenuity, integral logic, and authoritative force. This corrective scholarship and critical intervention helped to redefine African worldviews and spirituality and, as such, showed how African religion is pivotal to the individual and communal existence of the people. Just as Muslim traders and sojourners introduced new world religions to North and West Africa, Western traders and missionaries introduced new world religions to the continent. Indigenous traditions, however, did not capitulate to these forms, but, rather, creatively domesticated the new faiths, absorbing new rituals and tenets into their own belief systems and responding to the exogenous modernity in its wake.

Space constraints permit me to cite only one example. When I was in Israel a few years ago, I stayed in a modest bed-and-breakfast inn near the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I ran into a co-resident, a famous Swiss author. When he heard that I came from Nigeria, he wanted to display his knowledge of Ocha tradition as a devotee of Oxhosi, God of Thunder in Afro-Brazilian heritage. When I told him I am a twin (Ibeji) in Yoruba tradition—and in principle a sacred being myself—he almost fell on the floor to pay homage! My credentials as a Harvard professor made little impression on him. Our parting a week later was hard for him! A proper ongoing study of Ifa in West Africa would enable us to understand how one group—the Yoruba of West Africa—encounters transcendence and the sacred in practicing their tradition in ways radically different from Western constructions of religion.

Through a profound process of orality, Ifa as an interpretive tradition espouses an epistemology, metaphysics, morality, and a set of ethical principles and political ideology. These elements are worth exploring and espousing. The first encounters are fascinating. Africans engaged Western enlightenment and religious traditions in serious dialogue and conversation, and responded by creating and interpreting their own modernity. While some Christian mission historians, such as J. D. Y. Peel, for example, correctly argue that the Yoruba had their own enlightenment (“Olaju”), this is always presented in the context of Christian conversion and is very much tied to the escalating Christian missionary movement. But Ifa divination predates Western modernity. Ifa’s religious thought system—friendlier to Islam than to Christianity—not only predates Islam but also engages Islam in serious conversation. One of my favorite Ifa narratives acknowledges to Yoruba Muslims that climbing Mount Arafat was the most significant act of the hajj. The stoning of the devil in the Ka’ba in Mecca was a disguise for rejecting the local Esu, the Yoruba god of fate and messenger of the gods. Esu was represented as a stone mound in the front yard of ancient Yoruba compounds. Ifa rejects the religious extremism of certain forms of radical Islam making life unbearable in today’s world. Many centuries ago, Ifa must have envisaged the possibility of Boko Haram’s Islamic extremist movement ravaging Nigeria today.

On the other hand, the Yoruba people encountered Europeans in dialogue rather than monologue. Similar to other West African communities, the Yoruba did not reject Western modernity but challenged its claim to ontological and epistemological superiority. During the era of Western religious and cultural encounters in Yorubaland, some children were named Oguntoyibo, signifying “Ogun (god of war and iron) is as powerful as the European god.” Some children received names such as Ifatoyinbo, “Ifa is as powerful as the white man’s god.” Such names and concepts illustrate the force and creative resistance of indigenous thought and its ability to engage Western modernity in rigorous debate. It is incorrect to assume that conversion to Islam or to Christianity dealt a deathblow to indigenous traditions. Despite conversion to Islam or to Christianity, Africans continue to accommodate an indigenous worldview that occupies a vital space in the African consciousness.

What is the implication of indigenous hermeneutics for scholars today? I suggest that, at the conceptual and theoretical levels, we begin to take this interpretive approach seriously. What, for example, is the notion of history and the sacred in Akan thought? And why should our work in critical theory not begin from indigenous hermeneutics before we invoke Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, or Jürgen Habermas as platforms for interpreting our own worldview and society? European theorists are important, and we need to know and understand them to engage in serious global cultural dialogue, but this does not mean that we should discard our traditions as noninterpretive traditions limited merely to ethnographic illustrations. They certainly represent interpretive traditions, and, when carefully studied, they form a solid foundation for theoretical frameworks used to study and decode these religions in our scholarship.

- John Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (Heinemann, 1969), 1.

- E. Bolaji Idowu, African Traditional Religion: A Definition (Orbis Books, 1973).

- Ambrose Moyo, “Religion in Africa,” in Understanding Contemporary Africa , ed. Donald Gordon and April Gordon (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001), 344.

- Vincent B. Khapoya, The African Experience (1994; Routledge, 2012).

- John Mbiti, chap. 7, “The Spirits,” in his Introduction to African Religion , 2nd ed. (Heinemann, 1991), 65–76.

- Khapoya, The African Experience .

- Laurenti Magesa, African Religions: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life (Orbis Books, 1997).

- John Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy , 2nd rev ed. (Heinemann, 1990), 2.

- One must resist the structuralist temptation that views myths as static, unchanging, and simply the productions of a peoples’ imagination about the cosmic order. See Luc De Heusch, “What Shall We Do with the Drunken King?,” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 45, no. 4 (1975): 363–72, esp. 364.

- V. Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge (Indiana University Press, 1998), 250.

- Unlike the Christian community, recited stories of creation are not performed by a single God, who ordered, by fiat, the creation of the universe with mere spoken words. Some biblical cosmological narratives have parallels in African cosmogony, for example, when the Supreme Being summons the hosts of heaven and declares to them, “Come let us make man in our own image.” This same script appears in the creation of the Yoruba world, when Olodumare designates to the Orisa (deities), the job of creating the universe.

- John Middleton, Encyclopedia of Africa South of the Sahara (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1997).

- Jacob K. Olupona, African Religions: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2014), 4.

- Jacob K. Olupona, Kingship, Religion, and Rituals in a Nigerian Community: A Phenomenological Study of Ondo Yoruba Festivals (Almqvist & Wiksell, 1991).

- Robert N. Bellah, “Civil Religion in America,” Daedalus 134, no. 4 (2005): 40–55.

- Jacob K. Olupona, City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination (University of California Press, 2011).

- Jacob K. Olupona, “Odun Ifa: Ifa Festival and Insight and Artistry in African Divination (review),” Research in African Literatures 34, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 225–29; “Owner of the Day and Regulator of the Universe: Ifa Divination and Healing among the Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria,” in Divination and Healing: Potent Vision , ed. Michael Winkelman and Philip M. Peek (University of Arizona Press, 2004), 103–17; Òrisà Devotion as World Religion: The Globalization of Yorùbá Religious Culture , ed. Jacob K. Olupona and Terry Rey (University of Wisconsin Press, 2008); and Ifá Divination, Knowledge, Power, and Performance , ed. Jacob K. Olupona and Rowland O. Abiodun (Indiana University Press, 2016).

- Apart from a few instances in West Africa, where women actually ruled as kings, the designation “queen” was not often used in isolation from the position itself (which was defined in male terms).

- E. Franklin Frazier, Black Bourgeoisie: The Book That Brought the Shock of Self-Revelation to Middle-Class Blacks in America (Simon & Schuster, 1957). I was inspired by Andrea Lee’s review of Lawrence Otis, Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class (Harper Collins, 1999), published in The New York Times Book Review , February 21, 1999.

- My essay “Omọ Òpìtańdìran, an Africanist Griot: Toni Morrison and African Epistemology, Myths, and Literary Culture,” in Goodness and the Literary Imagination , ed. Davíd Carrasco, Stephanie Paulsell, and Mara Willard (University of Virginia Press, 2019), is an attempt to begin a fresh conversation on this topic.

Jacob K. Olupona is Professor of African Religious Traditions at Harvard Divinity School and Professor of African and African American Studies in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. His many publications include African Religions: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2014); City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination (University of California Press, 2011); and Kingship, Religion, and Rituals in a Nigerian Community: A Phenomenological Study of Ondo Yoruba Festivals (Almqvist & Wiksell, 1991), which has become a model for ethnographic research among Yoruba-speaking communities. This article is an edited version of remarks he delivered for the annual Surjit Singh Lecture in Comparative Religious Thought and Culture at the Graduate Theological Union on April 28, 2020.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

I really love this, it’s helps alot

The presentation was insightful. it is only the Africans that can present the issues of Africa in the African way. Thank you

This was amazingly written. Truly opening my eyes on traditions, cultures and rituals that I did not know existed.

Thank you for this interesting essay on African religion.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About | Commentary Guidelines | Harvard University Privacy | Accessibility | Digital Accessibility | Trademark Notice | Reporting Copyright Infringements Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

African religions summary

Learn about indigenous african religions and their corresponding beliefs and practices.

African religions , Indigenous religions of the African continent. The introduced religions of Islam (in northern Africa) and Christianity (in southern Africa) are now the continent’s major religions, but traditional religions still play an important role, especially in the interior of sub-Saharan Africa. The numerous traditional African religions have in common the notion of a creator god, who made the world and then withdrew, remaining remote from the concerns of human life. Prayers and sacrificial offerings are usually directed toward secondary divinities, who are intermediaries between the human and sacred realms. Ancestors also serve as intermediaries ( see ancestor worship). Ritual functionaries include priests, elders, rainmakers, diviners, and prophets. Rituals are aimed at maintaining a harmonious relationship with cosmic powers, and many have associated myths that explain their significance. Animism is a common feature of African religions, and misfortune is often attributed to witchcraft and sorcery.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

EVs fight warming but are costly. Why aren’t we driving $10,000 Chinese imports?

Toll of QAnon on families of followers

The urgent message coming from boys

The spirituality of africa.

Jacob Olupona, professor of indigenous African religions at Harvard Divinity School and professor of African and African-American studies in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, recently sat down for an interview about his lifelong research on indigenous African religions. “The success of Christianity and Islam on the African continent in the last 100 years has been extraordinary, but it has been, unfortunately, at the expense of African indigenous religions,” said Olupona.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Anthony Chiorazzi

Harvard Correspondent

Though larger religions have made big inroads, traditional belief systems, which are based on openness and adaptation, endure

One of Jacob Olupona’s earliest memories in Massachusetts is of nearly freezing in his apartment as a graduate student at Boston University during the great snowstorm of 1978. “I had it. I told my father that I was coming home,” he recalled. But after braving that first blizzard in a land far from his native Nigeria, Olupona stuck it out and earned his Ph.D. He went on to conduct some of the most significant research on African religions in decades.

Olupona, professor of indigenous African religions at Harvard Divinity School and professor of African and African-American studies in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, recently sat down for an interview about his lifelong research on indigenous African religions.

Olupona earned his bachelor of arts degree in religious studies from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1975. He later earned both an M.A. (1981) and Ph.D. (1983) in the history of religions from Boston University.

Authoring or editing more than half a dozen books on religion and African culture (including the recent “African Religions: A Very Short Introduction,” Oxford University Press), Olupona has researched topics ranging from the indigenous religions of Africa to the religious practices of Africans who have settled in America. His research has helped to introduce and popularize new concepts in religious studies, such as the term “reverse missionaries,” referring to African prelates sent to Europe and the United States.

The recipient of many prestigious academic honors and research fellowships, Olupona also received the 2015–2016 Reimar Lust Award for International and Cultural Exchange, considered one of Germany’s most prestigious academic honors. The award allows Olupona a year of study and research in Germany; he is on leave this year (2015–16).

Much of Olupona’s work is an attempt to provide a fuller understanding of the complexity and richness of African indigenous thought and practice by viewing it not as a foil or as a useful comparative to better understand Western religions, but as a system of thought and belief that should be valued and understood for its own ideas and contribution to global religions.

GAZETTE: How would you define indigenous African religions?

OLUPONA: Indigenous African religions refer to the indigenous or native religious beliefs of the African people before the Christian and Islamic colonization of Africa. Indigenous African religions are by nature plural, varied, and usually informed by one’s ethnic identity, where one’s family came from in Africa. For instance, the Yoruba religion has historically been centered in southwestern Nigeria, the Zulu religion in southern Africa, and the Igbo religion in southeastern Nigeria.

“African spirituality simply acknowledges that beliefs and practices touch on and inform every facet of human life, and therefore African religion cannot be separated from the everyday or mundane.”

For starters, the word “religion” is problematic for many Africans, because it suggests that religion is separate from the other aspects of one’s culture, society, or environment. But for many Africans, religion can never be separated from all these. It is a way of life, and it can never be separated from the public sphere. Religion informs everything in traditional African society, including political art, marriage, health, diet, dress, economics, and death.

This is not to say that indigenous African spirituality represents a form of theocracy or religious totalitarianism — not at all. African spirituality simply acknowledges that beliefs and practices touch on and inform every facet of human life, and therefore African religion cannot be separated from the everyday or mundane. African spirituality is truly holistic. For example, sickness in the indigenous African worldview is not only an imbalance of the body, but also an imbalance in one’s social life, which can be linked to a breakdown in one’s kinship and family relations or even to one’s relationship with one’s ancestors.

GAZETTE: How have ancestors played a role in traditional societies?

OLUPONA: The role of ancestors in the African cosmology has always been significant. Ancestors can offer advice and bestow good fortune and honor to their living dependents, but they can also make demands, such as insisting that their shrines be properly maintained and propitiated. And if these shrines are not properly cared for by the designated descendant, then misfortune in the form of illness might befall the caretaker. A belief in ancestors also testifies to the inclusive nature of traditional African spirituality by positing that deceased progenitors still play a role in the lives of their living descendants.

GAZETTE: Are ancestors considered deities in the traditional African cosmology?

OLUPONA: Your question underscores an important facet about African spirituality: It is not a closed theological system. It doesn’t have a fixed creed, like in some forms of Christianity or Islam. Consequently, traditional Africans have different ideas on what role the ancestors play in the lives of living descendants. Some Africans believe that the ancestors are equal in power to deities, while others believe they are not. The defining line between deities and ancestors is often contested, but overall, ancestors are believed to occupy a higher level of existence than living human beings and are believed to be able to bestow either blessings or illness upon their living descendants.

GAZETTE: In trying to understand African spirituality, is it helpful to refer to it as polytheistic or monotheistic?

OLUPONA: No, this type of binary thinking is simplistic. Again, it doesn’t reflect the multiplicity of ways that traditional African spirituality has conceived of deities, gods, and spirit beings. While some African cosmologies have a clear idea of a supreme being, other cosmologies do not. The Yoruba, however, do have a concept of a supreme being, called Olorun or Olodumare , and this creator god of the universe is empowered by the various orisa [deities] to create the earth and carry out all its related functions, including receiving the prayers and supplications of the Yoruba people.

GAZETTE: What is the state of indigenous African religions today?

OLUPONA: That’s a mixed bag. Indigenous African spirituality today is increasingly falling out of favor. The amount of devotees to indigenous practices has dwindled as Islam and Christianity have both spread and gained influence throughout the continent.

According to all the major surveys, Christianity and Islam each represent approximately 40 percent of the African population. Christianity is more dominant in the south, while Islam is more dominant in the north. Indigenous African practices tend to be strongest in the central states of Africa, but some form of their practices and beliefs can be found almost anywhere in Africa.

Nevertheless, since 1900, Christians in Africa have grown from approximately 7 million to over 450 million today. Islam has experienced a similar rapid growth.

Yet consider that in 1900 most Africans in sub-Saharan Africa practiced a form of indigenous African religions.

The bottom line then is that Africans who still wholly practice African indigenous religions are only about 10 percent of the African population, a fraction of what it used to be only a century ago, when indigenous religions dominated most of the continent. I should add that without claiming to be full members of indigenous traditions, there are many professed Christians and Muslims who participate in one form of indigenous religious rituals and practices or another. That testifies to the enduring power of indigenous religion and its ability to domesticate Christianity and Islam in modern Africa.

The success of Christianity and Islam on the African continent in the last 100 years has been extraordinary, but it has been, unfortunately, at the expense of African indigenous religions.

GAZETTE: But yet you said it’s a mixed bag?

OLUPONA: Yes, it’s a mixed bag because in the African diaspora — mostly due to the slave trade starting in the 15th century — indigenous African religions have spread and taken root all over the world, including in the United States and Europe. Some of these African diaspora religions include Cuban Regla de Ocha, Haitian Vodou, and Brazilian Candomble. There is even a community deep in the American Bible Belt in Beaufort County, S.C., called Oyotunji Village that practices a type of African indigenous religion, which is a mixture of Yoruba and Ewe-Fon spiritual practices.

One of the things these diaspora African religions testify to is the beauty of African religions to engage a devotee on many spiritual levels. A follower of African diaspora religions has many choices in terms of seeking spiritual help or succor. For example, followers can seek spiritual direction and relief from healers, medicine men and women, charms [adornments often worn to incur good luck], amulets [adornments often used to ward off evil], and diviners [spiritual advisers].

I should also state that there are signs of the revival of African indigenous practices in many parts of Africa. Modernity has not put a total stop to its influence. Ritual sacrifices and witchcraft beliefs are still common. Moreover, the religions developed in the Americas impact Africa in that devotees of the African diaspora have significant influence on practices in Africa. Some African diasporans are returning to the continent to reconnect with their ancestral traditions, and they are encouraging and organizing the local African communities to reclaim this heritage.

GAZETTE: It sounds like African indigenous religions are dynamic, inclusive, and flexible.

OLUPONA: Yes, and the pluralistic nature of African-tradition religion is one of the reasons for its success in the diaspora. African spirituality has always been able to adapt to change and allow itself to absorb the wisdom and views of other religions, much more than, for example, Christianity and Islam. While Islam and Christianity tend to be overtly resistant to adopting traditional African religious ideas or practices, indigenous African religions have always accommodated other beliefs. For example, an African amulet might have inside of it a written verse from either the Koran or Christian Bible. The idea is that the traditional African practitioner who constructed that amulet believes in the efficacy of other faiths and religions; there is no conflict in his mind between his traditional African spirituality and another faith. They are not mutually exclusive. He sees the “other faith” as complementing and even adding spiritual potency to his own spiritual practice of constructing effective amulets. Indigenous African religions are pragmatic. It’s about getting tangible results.

GAZETTE: What allows African indigenous religions to be so accommodating?

OLUPONA: One of the basic reasons is that indigenous African spiritual beliefs are not bound by a written text, like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Indigenous African religion is primarily an oral tradition and has never been fully codified; thus, it allows itself to more easily be amended and influenced by other religious ideas, religious wisdom, and by modern development. Holding or maintaining to a uniform doctrine is not the essence of indigenous African religions.

GAZETTE: What will Africa lose if it loses its African indigenous worldview?

OLUPONA: We would lose a worldview that has collectively sustained, enriched, and given meaning to a continent and numerous other societies for centuries through its epistemology, metaphysics, history, and practices.

For instance, if we were to lose indigenous African religions in Africa, then diviners would disappear, and if diviners disappeared, we would not only lose an important spiritual specialist for many Africans, but also an institution that for centuries has been the repository of African history, wisdom, and knowledge. Diviners — who go through a long educational and apprenticeship program — hold the history, culture, and spiritual traditions of the African people. The Yoruba diviners, for example, draw on this extensive indigenous knowledge every day by consulting Ifa, an extensive literary corpus of information covering science, medicine, cosmology, and metaphysics. Ifa is an indispensable treasure trove of knowledge that can’t be duplicated elsewhere; much of its knowledge has been handed down from babalawo [Ifa priest/diviner] to babalawo for centuries. (I myself have consulted with several diviners for my research on specific academic topics regarding African culture and history; consequently, if we were to lose Africa’s diviners, we would also lose one of Africa’s best keepers and sources of African history and culture. That would be a serious loss not only for Africans, but also for academics, researchers, writers, and general seekers of wisdom the world over.

GAZETTE: What else would we lose if we lost traditional African Religions?

OLUPONA: If we lose traditional African religions, we would also lose or continue to seriously undermine the African practice of rites of passage such as the much cherished age-grade initiations, which have for so long integrated and bought Africans together under a common understanding, or worldview. These initiation rituals are already not as common in Africa as they were only 50 years ago, yet age-grade initiations have always helped young Africans feel connected to their community and their past. They have also fostered a greater feeling of individual self-worth by acknowledging important milestones in one’s life, including becoming an adult or an elder.

In lieu of these traditional African ways of defining oneself, Christianity and Islam are gradually creating a social identity in Africa that cuts across these indigenous African religious and social identities. They do this by having Africans increasingly identify themselves as either Muslim or Christian, thus denying their unique African worldview that has always viewed — as evidenced in their creation myths — everything as unified and connected to the land, the place were one’s clan, lineage, and people were cosmically birthed. Foreign religions simply don’t have that same connection to the African continent.

GAZETTE: How do you balance your Christian and indigenous African identity?

OLUPONA: I was raised in Africa during the 1960s, when the Yoruba community never asked you to chose between your personal faith and your collective African identity. But today that is not the case due to more exclusive-minded types of Christianity and Islam that see patronizing indigenous African beliefs and practices as violating the integrity of their Christian or Muslim principles, but I believe that one can maintain one’s religious integrity and also embrace an African worldview.

GAZETTE: How can you do that?

OLUPONA: My father, a faithful Anglican priest, was a good example. Everywhere he went in southwestern Nigeria, he never opposed or spoke out against African culture — including initiation rites, festivals, and traditional Yoruba dress — as long as it didn’t directly conflict with Christianity.

For myself, I negotiate between my Yoruba and Christian identity by, for example, affirming those aspects of African culture that promote good life and communal human welfare. For instance, in a few years time, I pray that I will be participating in an age-grade festival — for men around 70 years of age — called Ero in my native Nigerian community in Ute, in Ondo state. I won’t pray to an orisa, but I will affirm the importance of my connection with members of my age group. In respect and honor of my culture, I also dress in my traditional Nigerian attire when I’m in my country. I also celebrate and honor the king’s festivals and ceremonies in my hometown and other places where I live and do research. Additionally, I will not discourage, disparage, or try and convert those who practice their form of African indigenous religions. Maybe this is why I am not an Anglican priest.